Abstract

Controlled donation after circulatory determination of death (DCD), where death is determined after cardiac arrest, has been responsible for the largest quantitative increase in Canadian organ donation and transplants, but not for heart transplants. Innovative international advances in DCD heart transplantation include direct procurement and perfusion (DPP) and normothermic regional perfusion (NRP). After death is determined, DPP involves removal and reanimation of the arrested heart on an ex situ organ perfusion system. Normothermic regional perfusion involves surgically interrupting (ligating the aortic arch vessels) brain blood flow after death determination, followed by restarting the heart and circulation in situ using extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. The objectives of this Canadian consensus building process by a multidisciplinary group of Canadian stakeholders were to review current evidence and international DCD heart experience, comparatively evaluate international protocols with existing Canadian medical, legal, and ethical practices, and to discuss implementation barriers. Review of current evidence and international experience of DCD heart donation (DPP and NRP) determined that DCD heart donation could be used to provide opportunities for more heart transplants in Canada, saving additional lives. Although candid discussion identified a number of potential barriers and challenges for implementing DCD heart donation in Canada, it was determined that DPP implementation is feasible (pending regulatory approval for the use of an ex situ perfusion device in humans) and in alignment with current medical guidelines for DCD. Nevertheless, further work is required to evaluate the consistency of NRP with current Canadian death determination policy and to ensure the absence of brain perfusion during this process.

Résumé

Le don contrôlé après un décès circulatoire (DDC), cas dans lequel le décès est déterminé après un arrêt cardiaque, est à l’origine de la plus forte augmentation quantitative des dons et des transplantations d’organes au Canada, sauf pour les transplantations cardiaques. Parmi les progrès internationaux novateurs dans la transplantation cardiaque après DDC, citons l’obtention directe et perfusion (ODP) et la circulation régionale normothermique (CRN). Une fois le décès déterminé, l’ODP consiste à retirer et réanimer le cœur arrêté sur un système de perfusion ex situ. La circulation régionale normothermique consiste à interrompre de manière chirurgicale (en ligaturant les vaisseaux de l’arc aortique) le flux sanguin au cerveau après la détermination du décès, puis à redémarrer le cœur et la circulation in situ utilisant l’oxygénation par membrane extracorporelle (ECMO). Les objectifs de ce processus canadien d’établissement de consensus par un groupe multidisciplinaire d’intervenants canadiens étaient d’examiner les données probantes et les expériences internationales actuelles en matière de DDC, d’évaluer comparativement les protocoles internationaux par rapport aux pratiques médicales, juridiques et éthiques canadiennes existantes, et de discuter des obstacles à la mise en œuvre de tels protocoles. L’examen des données probantes et des expériences internationales actuelles en matière de don de cœur après DDC (ODP et CRN) a permis de déterminer que le don de cœur après DDC pourrait être utilisé afin de faire de plus nombreuses transplantations cardiaques au Canada, sauvant ainsi des vies supplémentaires. Bien que des discussions aient permis d’identifier plusieurs obstacles et défis potentiels à la mise en œuvre du don cardiaque après DDC au Canada, il a été déterminé que la mise en œuvre de l’ODP est réalisable (en attente de l’approbation réglementaire pour l’utilisation d’un dispositif de perfusion ex situ chez l’humain) et en accord avec les directives médicales actuelles concernant le DDC. Néanmoins, d’autres travaux sont nécessaires pour évaluer la conformité de la CRN aux politiques canadiennes actuelles de détermination de la mort et pour garantir l’absence de perfusion cérébrale au cours de ce processus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The implementation of controlled donation after circulatory determination of death (DCD) has been responsible for the largest quantitative increase in deceased donation and transplantation in Canada.1 Nevertheless, individuals on the heart transplant waiting list have not yet benefited from the advances in DCD. Withdrawal of life sustaining measures in patients with devastating brain injury who are potential DCD donors leads to cardiac arrest, and this has historically precluded utilization of the arrested and ischemic heart for transplantation. Figures 1 and 21 show the current status of heart transplantation in Canada relying exclusively on donation after neurologic determination of death (NDD, commonly referred to as brain death). From 2013 to 2017, there was an average of 163 adult heart transplants per year with up to 25% of adults on the wait list dying or being withdrawn from the list because of deterioration that precluded transplant. In children, the situation is dire, with a mean of 23 pediatric heart transplants per year and up to 50% incidence of death or withdrawal from the wait list.

Source: Canadian Organ Replacement Register, Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2018. Fig. 1b Number of adult patients waiting for a heart transplant, who withdrew from the waiting list, or died while waiting, Canada, 2013–2017. Absolute number of adult (18 yr of age or greater) patients waiting for a heart transplant, who withdrew from the waiting list, or died while waiting, in Canada, over five years. Patients waiting for a heart transplant include those who are “active” and can receive a transplant at any time, and patients who are “on hold” and cannot receive a transplant for a medical or other reason for a short period of time. Patients who withdrew from the waiting list were removed for one of the following reasons: (1) clinical improvement and patient no longer requires transplantation; (2) patient elects to be removed from the list; or (3) patient is too ill to undergo transplantation and his or her condition is not deemed to be short term. Source: Canadian Organ Replacement Register, Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2018.

a Number of adult heart transplants, by province, Canada, 2013–2017. Absolute number of adult (18 yr of age or greater) heart transplants performed, by province, in Canada, over five years.

Source: Canadian Organ Replacement Register, Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2018. Fig. 2b Number of pediatric patients waiting for a heart transplant, who withdrew from the waiting list, or died while waiting, Canada, 2013–2017. Absolute number of pediatric (less than 18 yr of age) patients waiting for a heart transplant, who withdrew from the waiting list, or died while waiting, in Canada, over five years. Patients waiting for a heart transplant include those who are “active” and can receive a transplant at any time, and patients who are “on hold” and cannot receive a transplant for a medical or other reason for a short period of time. Patients who withdrew from the waiting list were removed for one of the following reasons: (1) clinical improvement and patient no longer requires transplantation; (2) patient elects to be removed from the list; or (3) patient is too ill to undergo transplantation and his or her condition is not deemed to be short term. Source: Canadian Organ Replacement Register, Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2018.

a Number of pediatric heart transplants, by province, Canada, 2013–2017. Absolute number of pediatric (less than 18 yr of age) heart transplants performed, by province, in Canada, over five years. 1

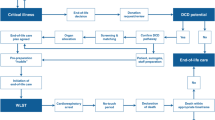

Two innovative methods have been developed to allow for recovery and transplantation of hearts after cardiac arrest from DCD donors: normothermic regional perfusion (NRP) and direct procurement and perfusion (DPP). These procedures have been used successfully in the United Kingdom (UK) (NRP and DPP)2 and in Australia (DPP)3 to increase the number of hearts available for transplant. After death is determined in DCD, DPP involves direct removal of the heart and reanimation of heart function on an ex situ (outside of the body) organ perfusion system. NRP involves surgically interrupting (clamping and ligating the aortic arch vessels) brain blood flow after death determination, followed by restarting the heart and circulation in situ (in the donor’s body) using extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). The purpose of precluding brain blood flow after death is to prevent any brain perfusion or reanimation of function. Figure 4 contrasts the differences in DCD procedures of NRP, DPP, and current DCD practice in Canada. Australia currently does not permit NRP as it contravenes existing laws for DCD where death is defined as the irreversible cessation of blood circulation in the body of the person.4,5 In the UK, the definition of death is brain-based; as long as NRP does not restore brainstem perfusion after death has been confirmed then it is consistent with laws for death determination6 and therefore both DPP and NRP are permissible.

Several Canadian heart transplant programs, including those with ongoing animal-based research programs in DCD heart transplantation, have expressed interest in DPP7 and NRP.8 Canadian Blood Services and Trillium Gift of Life Network collaborated to organize a two-day consensus building process, held on 15–16 October 2018, for relevant stakeholders to develop expert guidance for the possible implementation of DCD heart donation in Canada.

Scope

The work performed prior to and during the two-day consensus building process will inform organ donation organizations, heart transplant programs, hospitals, and provincial governments and health authorities looking for guidance in evaluating whether to offer the opportunity for heart donation and transplantation by DCD in the context of their own regional and provincial needs and resources.

The scope of the consensus building process included adult and pediatric heart donation and transplantation, donor care, donor and recipient consent, pre- and post-mortem interventions, definition of death, and the criteria for death determination. Not in scope were the potential ethical issues surrounding the provision of DCD in general, economic analyses, the dead donor rule, and rules for the allocation of DCD hearts. Thoraco-abdominal organ (lung, kidney, liver, pancreas) recovery using NRP was also out of scope, though it was recognized that this would be discussed in the context of using NRP for the heart and the associated impacts on the retrieval of other organs.

The objectives of the consensus building process were to review current evidence and international DCD heart experience, comparatively evaluate international protocols with existing Canadian medical, legal, and ethical practices and perspectives, and to discuss barriers and challenges of implementing DPP and/or NRP heart donation and transplantation in Canada.

Methods

The planning committee (A.H., S.S., S.T., L.W., L.H., J.M., J.M., C.G.) with Canadian cardiac transplant advisors (M.B., D.F.) was established to develop the agenda for the consensus building process and to prepare background materials for review by participants in advance of the meeting. Experts were invited to the meeting from backgrounds that would intersect with the care of the DCD heart donor or recipient: critical care (physicians and nurses), neurocritical care, intensive care unit donation physicians, neurology, neurocritical care, cardiac transplant surgery, cardiology, perfusion services, bioethics, legal, death investigation, organ donation organizations, abdominal and thoracic surgery, organ donation and transplant research, and donor family and patient representatives. Research Ethics Board approval was not required nor sought for this conference. See full participant list in the Appendix.

The following professional societies were formally represented: Canadian Critical Care Society, Canadian Association of Critical Care Nurses, Operating Room Nurses Association of Canada, Canadian Society of Clinical Perfusion, Canadian Society of Transplantation, Canadian Donation and Transplant Research Program, Canadian Blood Services Bioethics Advisory Committee, Canadian Blood Services Heart Transplant Advisory Committee, and the National Forum of Chief Coroners and Chief Medical Examiners.

Emerging from the meeting, an Expert Review Group was assembled (planning committee: M.B., D.F., J.T., A.B., D.B., C.S.) to review the meeting outcomes, finalize the report, and assist in knowledge translation.

Development process

Prior to and during the consensus building process, participants reviewed the following information that would assist in the evaluation of the DPP and NRP methods:

-

Surveys of the public9 and of healthcare professionals10 that explored attitudes towards DCD heart donation and DPP/NRP

-

A bioethics review (eAppendix in the Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM])

-

Documents outlining existing DCD clinical guidelines in Canada and the current provincial legal statutes and framework for death determination in Canada (eAppendix, ESM)

-

A statement from the National Forum of Chief Coroners and Chief Medical Examiners (eAppendix, ESM)

-

Data on the annual number of heart transplants and recipients waiting in Canada, and on DCD heart donation potential in Ontario (Figs 1–3; Table 1).

Overview of current DCD protocols. High-level overview of three protocols for controlled donation after circulatory determination of death. The current Canadian protocol includes the procedures for recovery of all organs except the heart. Two additional protocols are used for heart recovery after controlled donation after circulatory determination of death in specific centres outside of Canada. DCD = controlled donation after circulatory determination of death; DPP = direct procurement and perfusion; ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; NRP = normothermic regional perfusion; SBP = systolic blood pressure.

Participants heard from the following international experts:

-

Dr. Kumud Dhital, a cardiothoracic specialist and transplant surgeon from St. Vincent's Hospital in Sydney, Australia

-

Dr. Dale Gardiner, Deputy National Clinical Lead for Organ Donation for National Health Service Blood and Transplant in the UK and a consultant in adult intensive care medicine from Nottingham University Hospitals National Health Service Trust

-

Mr. Stephen Large, Consultant Surgeon from the Papworth Hospital National Health Service Foundation Trust.

Discussions were held in small groups, panels and in plenary to address specific questions, including the advantages and disadvantages of DCD heart implementation, alignment with and impacts on current Canadian practices, and barriers, challenges, concerns and opportunities associated with both the DPP and NRP methods. Discussions and debate were informed by panels of: 1) subject matter experts in bioethics, law, public/professional surveyors, coroner/medical examiner; 2) heart transplant recipients and family members who gave consent for organ and/or tissue donation by DCD on behalf of their loved ones; 3) Canadian heart transplant surgeons; and 4) Canadian intensive care death determination experts. Final participant consensus recommendations for DPP vs NRP were conducted via nominal group technique. See eAppendix (ESM) for additional information.

Management of competing interests

All participants signed a confidentiality agreement upon arrival at the venue, where they were also asked to disclose any potential professional and financial conflicts of interest. These declarations were then reviewed by the planning committee. Several participants have professional roles in organ donation administration for governmental not-for-profit entities or funded scientific research; however, none of the participants were considered to have a relevant financial conflict of interest. All presenters declared their competing interests prior to their presentations.

Results

Table 2 summarizes the advantages and disadvantages of DPP and NRP identified by meeting participants. Key outcomes of the consensus building process are presented below. More information on the background documents, information presented, and discussions that took place can be found in the full guidance document (eAppendix, ESM).

-

1.

According to the preliminary results of the surveys, there is professional and public support for DCD heart donation and transplantation in Canada.9,10

-

2.

There is an opportunity to increase the number of heart transplants through DCD, but it must be done in a way that protects all potential donors and recipients and safeguards public and professional trust.

-

3.

Challenges were identified related to human resource requirements, logistics, cost, and system capacity for both DPP and NRP.

-

4.

International experience to 31 March 2019 (n = 105 in adults) shows good short to medium term outcomes for both NRP and DPP, but insufficient data exists for long-term outcomes or for comparing NRP vs DPP outcomes. Recent published data show a one-, three-, and five-year survival of 96%, 94%, and 94% respectively for DPP heart DCD in Australia.11 Single-centre UK data on NRP and DPP heart DCD shows DCD heart donation increased overall heart transplant activity at Royal Papworth Hospital by 48% with no difference in intensive care unit length of stay and 30-day or one-year survival compared with conventional donation after brain death heart transplants.12

-

5.

Direct procurement and perfusion align with existing Canadian guidelines for DCD13,14 where ex situ organ evaluation is already in place (e.g., lungs, liver, kidneys). Therefore, there are compelling reasons to advance this practice in Canada without delay.

-

6.

While DCD heart transplant could provide the greatest impact for infants and children, there has been limited pediatric experience and ex situ perfusion devices are only just being developed for children.

-

7.

Further investigation is needed to address the medical and ethical acceptability of NRP and to identify the impact of NRP on organs other than the heart.

-

8.

Participants identified the need to clarify issues regarding death determination, especially with respect to NRP:

-

Concerns were raised regarding acceptability and validity of the required surgical interruption of brain blood flow following death determination and the lack of confirmation of the cessation of brain blood flow and function, as currently practiced. Despite the interruption of brain arterial supply from the aortic arch, there may be risks for accessory collateral arterial supply to the brain in any potential DCD heart donor. The potential for collateral arterial flow to generate brain perfusion will depend on the amount of anterograde flow and arterial pressure generated to overcome intracranial pressure. It is unclear what degree of brain perfusion may be associated with risks of resumption of brain function. In potential donors with pre-existing brain injury and elevations of intracranial pressure, a higher level of collateral flow and pressure would be required to generate brain perfusion. For conscious and competent patients, such as those undergoing medical assistance in dying, who do not have pre-existing devastating brain injury associated with elevations of intracranial pressure, any collateral arterial supply to the brain may be theoretically more likely to generate brain perfusion and resumption of brain function.

-

Alignment is needed between Canadian medical guidelines for DCD where death determination definitions differ (cessation of circulation and/or brain function).

-

Based on deliberations and outcomes from the meeting, authors suggest that jurisdictions should consider the use of NRP based on the following logic model:

If:

-

1.

The surgical act of ligating or dividing the aortic arch vessels after confirmation of death and before starting NRP is medically and ethically acceptable

-

2.

Death in DCD is defined by the permanent cessation of circulation to the brain

-

3.

Absence of potential for brain perfusion can be assured (to adhere to the principle of permanence for death).

Then:

-

4.

Restarting the circulation after death does not invalidate the definition of death in DCD

-

5.

Restarting the heart in the donor’s body after death does not invalidate the definition of death in DCD

-

6.

Normothermic regional perfusion may be considered permissible.

Discussion

There are no published guidelines for policies and the practice of DCD heart donation and transplantation in Canada. There are two Canadian guidelines (one adult,13 one pediatric14) for DCD; however, the adult guidelines do not consider heart donation and transplantation and the pediatric guidelines consider it only in the context of a research protocol. Specifically, the pediatric guidelines for DCD advises that recovery and transplantation of the heart is consistent with the dead donor rule. Considering the lack of published experience at the time of its publication, the previous guideline suggests heart transplant programs establish criteria for acceptance of heart donation, ex situ cardiac perfusion protocols, and heart allocation in pediatric DCD. The guideline also suggests cardiac programs for pediatric DCD be initiated under the supervision of a clinical trial or innovative therapy program.

Based on the outcomes of the consensus building process, the guidance panel agreed that implementation of DPP is feasible and in alignment with current Canadian medical, legal, and ethical guidelines for DCD, pending regulatory approval for the use of an ex situ perfusion device in humans. Further work is necessary to address the medical, ethical, and legal framework for NRP in the Canadian context. Principal challenges with NRP to resolve include consistency with current concepts and practices of death determination after cardiac arrest, the act of surgical interruption of brain blood flow and whether this surgical interruption of aortic arch vessels ensures cessation of brain blood flow from collateral sources.

There is no specific timeline to update this guidance for policy, but any changes to the DCD heart donation and transplantation process and/or DCD guidelines would require a review of this document to ensure that it covers any new ethical or practical concerns.

Gaps in knowledge and research questions

At the time of the meeting, there was limited worldwide experience with DCD heart transplantation. More data are needed to make further comparisons between DPP, NRP, and NDD donors. Two “listening posts” assigned to collect information during the consensus building process identified knowledge gaps and research questions (see Table 3).

As mentioned, economic analyses were beyond the scope of the meeting given insufficient information is available to assess the financial impact of either DPP or NRP, nor to compare costs between the two. In addition, economic health assessment expertise was not available during the discussion. Nonetheless, there was consensus that further economic assessment is needed. It was suggested that an economic assessment of DPP, NRP with ex situ perfusion, and NRP with cold storage be completed. Several individuals have begun this work in part.

Post meeting, the Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee (OHTAC) completed a health technology assessment for the use of portable cardiac perfusion systems in DCD. OHTAC uses established scientific methods to analyze evidence and develop assessments of new and existing healthcare services and medical devices and make recommendations on whether these services and devices should be publicly funded in Ontario. Based on this assessment, Health Quality Ontario, under the guidance of OHTAC, has recommended portable cardiac perfusion systems for use in DCD cases be publicly funded, conditional on Health Canada approval. The draft recommendation has been published on the Health Quality Ontario website.15

Conclusion

Review of current evidence and international experience of DCD heart donation (DPP and NRP) by a multidisciplinary group of Canadian stakeholders determined that DCD heart donation could be used to provide opportunities for more heart transplants in Canada, resulting in additional lives saved. Although candid discussion identified a number of potential barriers and challenges for implementing DCD heart donation (DPP and NRP) in Canada, upon evaluation of each of these procedures against Canadian medical, legal, and ethical practices, it was determined that DPP implementation is feasible (pending regulatory approval for the use of an ex situ perfusion device in humans) and in alignment with current medical guidelines for DCD. Nevertheless, further work is needed to address and respond to several medical, legal, and ethical concerns for NRP implementation.

References

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Canadian Organ Replacement Register, e-Statistics on Organ Transplants, Waiting Lists and Donors - 2018. Available from URL: https://www.cihi.ca/en/e-statistics-on-organ-transplants-waiting-lists-and-donors (accessed October 2020).

Messer S, Page A, Axell R, et al. Outcome after heart transplantation from donation after circulatory-determined death donors. J Heart Lung Transplant 2017; 36: 1311-8. Erratum: 2018; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healun.2017.10.021.

Chew HC, Iyer A, Connellan M, et al. Outcomes of donation after circulatory death heart transplantation in Australia. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019; 73: 1447-59.

Government of South Australia. Death (Definition) Act - 1983. Updated 2002. Available from URL: https://www.legislation.sa.gov.au/LZ/C/A/DEATH%20(DEFINITION)%20ACT%201983.aspx (accessed October 2020).

Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society (ANZICS). The Statement on Death and Organ Donation. Camberwell: Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society; 2013. Updated 2019. Available from URL: https://www.anzics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/ANZICS-Statement-on-Death-and-Organ-Donation-Edition-4.pdf (accessed October 2020).

Academy of Medical Royal Colleges. A Code of Practice for the Diagnosis and Confirmation of Death - 2008. Available from URL: http://aomrc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Code_Practice_Confirmation_Diagnosis_Death_1008-4.pdf (accessed October 2020).

White CW, Ali A, Hasanally D, et al. A cardioprotective preservation strategy employing ex vivo heart perfusion facilitates successful transplant of donor hearts after cardiocirculatory death. J Heart Lung Transplant 2013; 32: 734-43.

Ribeiro RV, Alvarez JS, Yu F, et al. Hearts donated after circulatory death and reconditioned using normothermic regional perfusion can be successfully transplanted following an extended period of static storage. Circ Heart Fail 2019; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.118.005364.

Honarmand K, Parsons Leigh J, Martin CM, et al. Acceptability of cardiac donation after circulatory determination of death: a survey of the Canadian public. Can J Anesth 2020; 67: 292-300.

Honarmand K, Parsons Leigh J, Basmaji J, et al. Attitudes of healthcare providers towards cardiac donation after circulatory death: a Canadian nation-wide survey. Can J Anesth 2020; 67: 301-12.

Dhital K, Ludhani P, Scheuer S, Connellan M, Macdonald P. DCD donations and outcomes of heart transplantation: the Australian experience. Indian J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2020; 36(Suppl 2): 224-32.

Messer S, Cernic S, Page A, et al. 5-Year single centre early experience of heart transplantation from donation after circulatory determined death (DCD) donors. J Heart Lung Transplant 2020; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healun.2020.10.001.

Shemie SD, Baker AJ, Knoll G, et al. National recommendations for donation after cardiocirculatory death in Canada: donation after cardiocirculatory death in Canada. CMAJ 2006; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.060895.

Weiss MJ, Hornby L, Rochwerg B, et al. Canadian guidelines for controlled pediatric donation after circulatory determination of death-summary report. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2017; 18: 1035-46. Erratum: 2018; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/pcc.0000000000001415.

Health Quality Ontario. Portable normothermic cardiac perfusion system in donation after cardiocirculatory death: a health technology assessment. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2020; 20: 1-90. Available from URL: https://www.hqontario.ca/Evidence-to-Improve-Care/HealthTechnology-Assessment/Reviews-And-Recommendations/Portable-Normothermic-Cardiac-PerfusionSystem-in-Donation-After-Cardiocirculatory-Death (accessed October 2020).

Acknowledgements

With special thanks going to Mr. Sylvain Bédard, Ms. Heather Berrigan, Ms. Diana Brodrecht, Mr. Thomas Shing, Mr. Everad Tilokee, and Mr. Jonathan Towers—our donor family and patient partners, whose experiential knowledge was openly shared during their full participation throughout the meeting. Their perspectives kept the meeting focused on the overarching purpose that drove this initiative—providing high-quality end-of-life care and organ donation options for dying patients while protecting their interests, supporting grieving families, and improving transplant opportunities for patients on waitlists. We would also like to thank Dorothy Strachan, from Strachan-Tomlinson, for assistance is finalizing the meeting agenda.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sam D. Shemie, Sylvia Torrance, Lindsay Wilson, Laura Hornby, Janet MacLean, Jim Mohr, Clay Gillrie, and Andrew Healey initiated the guidance development project and participated in the design and administration of the consensus building process, including the collection of information and data. All authors participated in the preparation of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

Trillium Gift of Life Network is the Government of Ontario agency responsible for planning, promoting, coordinating, and supporting organ and tissue donation and transplantation across Ontario. Canadian Blood Services and Trillium Gift of Life Network assume no responsibility or liability for any consequences, losses or injuries, foreseen or unforeseen, whatsoever or howsoever occurring, which might result from the implementation, use, or misuse of any information or guidance in this report. This report contains guidance that must be assessed in the context of a full review of applicable medical, legal, and ethical requirements in any individual case. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of the federal, provincial, or territorial governments.

Funding statement

This meeting was supported financially by Canadian Blood Services through a contribution from Health Canada in support of developing leading practices, and Trillium Gift of Life Network. Canadian Blood Services is a national, not-for-profit charitable organization. In the domain of organ and tissue donation and transplantation, it provides national services in the development of leading practices, system performance measurement, interprovincial organ sharing registries, and public awareness and education. Canadian Blood Services is not responsible for the management or funding of any Canadian organ donation organizations or transplant programs. Canadian Blood Services receives its funding from the provincial and territorial Ministries of Health and from the federal government (through Health Canada).

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Gregory L. Bryson, Former Deputy Editor-in-Chief, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Endorsed by the Canadian Critical Care Society, Canadian Society of Transplantation, Canadian Donation and Transplantation Research Program, Canadian Association of Critical Care Nurses, Canadian Society of Clinical Perfusion, and the Operating Room Nurses Association of Canada.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the Supplementary Information.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shemie, S.D., Torrance, S., Wilson, L. et al. Heart donation and transplantation after circulatory determination of death: expert guidance from a Canadian consensus building process. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 68, 661–671 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-021-01926-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-021-01926-2