Abstract

Purpose

In this review, we examine the association between physician professional behaviour and indicators measuring patient outcomes and satisfaction with care as well the potential for complaints, discipline, and litigation against physicians. We also review issues related to the structured teaching of professionalism to anesthesia residents, including resident evaluation.

Source

A search of the OVID Medline and PubMed databases was carried out using keywords relevant to the topics under consideration. Program directors of Canadian anesthesiology training programs were also surveyed to assess the current state of professionalism training and evaluation in their programs.

Principal findings

Unprofessional behaviour is frequently manifested in practice by medical students, residents, and physicians, and it is associated with personality characteristics that are evident early in training. There is a correlation between unprofessional physician behaviours and patient dissatisfaction, complaints, and lawsuits as well as adverse outcomes of care. Physician health and workplace relationships are negatively impacted by such behaviours. Canadian program directors recognize the need to approach the teaching of professionalism in an organized fashion during physician training.

Conclusions

A framework is provided for defining behavioural expectations, and mechanisms are offered for teaching and evaluating behaviours and responding to individuals with behaviours that persistently breach defined expectations. There is a need to define explicitly not only the expectations for behaviour but also the processes by which the behaviours will be assessed and documented. In addition, emphasis is placed on the nature, order, and magnitude of the responses to behaviours that do not meet expectations.

Résumé

Objectif

Dans cet article de synthèse, nous examinons l’association entre le comportement professionnel des médecins et des indicateurs mesurant les devenirs et la satisfaction des patients en ce qui touche aux soins, ainsi que le potentiel de plaintes, de mesures disciplinaires et de litiges contre les médecins. Nous passons également en revue les questions liées à l’enseignement structuré du professionnalisme aux résidents en anesthésie, y compris celles liées à l’évaluation des résidents.

Source

Une recherche a été effectuée dans les bases de données OVID Medline et PubMed à l’aide de mots-clés pertinents aux thèmes étudiés. Les directeurs de programmes canadiens de formation en anesthésiologie ont également répondu à un questionnaire afin d’évaluer l’état actuel de la formation et de l’évaluation du professionnalisme dans le cadre de leurs programmes.

Constatations principales

Les comportements non professionnels d’étudiants en médecine, de résidents et de médecins sont fréquemment observés dans la pratique, et ils sont associés à des traits de personnalité évidents assez tôt dans la formation. Il existe une corrélation entre les comportements non professionnels des médecins et l’insatisfaction des patients, les plaintes et les procès ainsi qu’avec l’évolution défavorable des soins prodigués. La santé des médecins et les relations sur le lieu de travail sont négativement influencées par de tels comportements. Les directeurs de programmes canadiens sont conscients qu’il est nécessaire d’organiser un enseignement du professionnalisme pendant la formation des médecins.

Conclusion

Un cadre est proposé afin de définir les attentes en matière de comportement; en outre, nous proposons des techniques d’enseignement et d’évaluation des comportements et de prise en charge des personnes dont les comportements sont constamment en-deçà des attentes prédéfinies. Il convient de définir de façon explicite non seulement les attentes en matière de comportement, mais également les processus d’évaluation et de documentation des comportements. En outre, l’emphase est mise sur la nature, l’ordre et l’ampleur des réactions aux comportements qui ne répondent pas aux attentes.

Similar content being viewed by others

In recent decades, the medical profession has come under increased scrutiny and greater criticism for both perceived and real breaches of professional attitudes and behaviour. Stories in the popular media have featured accounts of egregious behaviour on the part of individual physicians, and surveys reinforce a collective impression that the public has demoted physicians from their once lofty status as among the most trusted of professions. To its credit, the profession’s response has largely been to look inward and reflect on those values which should be integral to the practice of medicine. What has emerged from this introspection has been recognition and increasing consensus that the way forward is to refocus on the core values of professionalism in medical training and practice. The result of this process has been initiatives at every level of organized medicine to enhance expectations regarding the behaviour of physicians. When evaluating applicants, medical schools are moving away from the predominant emphasis on academic achievement and instead are utilizing evaluations of multiple domains, including assessments for behavioural integrity. Residency programs recognize that good behaviours and, in particular, behaviours defined as professional are associated with higher quality medical practice, and these behaviours are increasingly being sought and taught in medical training programs. Finally, hospitals and regulatory authorities increasingly clarify expectations for professional behaviour among practicing physicians and reinforce the notion that persistent unprofessional behaviour will result in eventual and inevitable sanctions.

The values reflected in professional physician behaviour are not new, just as the profession’s dedication to, and emphasis on, safe medical practice is not recent. Attributes of professionalism, such as those outlined by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (i.e., respect, compassion, integrity, responsiveness, altruism, ethics, commitment to excellence) have long been among the fundamental values desired in medical practitioners.Footnote 1 In the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada’s CanMEDS 2005 Physician Competency Framework, many of the same attributes are included in the competencies for the “Professional role”.1 While not explicitly defining professionalism, the Royal College document states that “the Professional Role is guided by codes of ethics and a commitment to clinical competence, the embracing of appropriate attitudes and behaviors, …and to the promotion of the public good within their domain” (Table 1). Perhaps what is new is the recognition that the desired behaviours and values do not occur by chance alone and cannot be absorbed passively as physicians in training progress through residency. Rather, medical training should and can be structured to teach and reinforce those values we desire in physicians. Additionally, continuing professional development programs can be modelled to ensure that professional behaviours are taught and reinforced among physicians in practice.

The objectives of this review are to assess the association between unprofessional physician behaviour and its impact on quality of health care and patient safety; relationships among care providers; and the health of the providers themselves. A framework is provided for defining behavioural expectations, methods are offered for teaching and evaluating behaviours, and mechanisms are given for responding to individuals with behaviours which persistently breach defined expectations. Emphasis is placed on the need to define explicitly the expectations for behaviour and the processes by which they will be assessed as well as the nature, order, and magnitude of the responses to behaviours which do not meet expectations. As well, similar emphasis is given to the importance of proper documentation to support the assessment and response to unprofessional behaviours as this step is integral to the operation of a fair and just process.

Methods

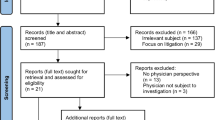

A literature search was carried out to support this narrative review on the topic of teaching professionalism to anesthesia residents in Canadian training programs and providing continuing professional development to faculty anesthesiologists in support of this initiative. Publications of interest to the authors were those dealing with the incidence of unprofessional behaviour in medical practice in general and anesthesia practice specifically; the early prediction of such behaviours; the impact of unprofessional behaviour on malpractice litigation; disciplinary actions by regulatory authorities; hospital complaints; as well as the impact of unprofessional behaviour on practitioner health, patient safety, and workplace relationships. Additionally, we carried out a search of literature relating to the teaching of professionalism to medical trainees in general and anesthesia residents in particular as well as issues relating to faculty providing professionalism training and evaluation. We searched the OVID Medline and PubMed databases using key phrases relevant to the above topics (i.e., “professionalism in medicine”, “professionalism in anesthesiology/anesthesia”, and “teaching professionalism”), and the bibliographies of the retrieved documents were then searched to retrieve additional publications relevant to the topics. The authors scanned the resulting publications and chose those most pertinent to the topics of interest for a more detailed review. Emphasis was placed on materials published in the last decade, although older publications were assessed if they were considered to be relevant. Although attempts were made to obtain a meaningful and representative sample of the literature, the search was not exhaustive. Finally, program directors of Canadian anesthesiology training programs were sent a brief and informal survey via E-mail to assess the current state of professionalism training and evaluation in their programs (Appendix).

Predicting problem patterns of behaviour in physicians

There is evidence that physician behaviour issues that eventually become problematic in medical practice are manifest and observable as early as medical school. Knights and Kennedy profiled the dysfunctional interpersonal tendencies of students selected into a medical program using self-reported measures of personality characteristics. Four factors accounted for the majority of the variance in behaviour: a decreased ability to work cooperatively; increased measures of aggressiveness, competitiveness, intimidation, and self-promotion; increased obsessive and critical behaviour; and the tendency to be indecisive and conforming.2 Interestingly, although conforming behaviour might promote collaboration, it can also result in a reluctance to take principled stands when required, and it is in this latter context that undesirable behaviour arises. Stern et al. reported the results of a retrospective cohort study conducted to establish indices for professional behaviour in medical students and to identify predictors of these index attributes.3 Significant predictors were found only in domains where students were given opportunities to demonstrate conscientious behaviour or humility in self-assessment. In particular, failure to complete required course evaluations and to report compliance with immunization schedules were significant predictors of unprofessional behaviour. Brenner et al. investigated whether data available at the time of residency application could be used to predict future problems of performance.4 The presence of any negative comments in the dean’s letter from the resident’s medical school of origin correlated significantly with future performance problems. Those who experienced major problems had correspondingly more negative comments in the dean’s letter than those with future minor problems.

Problematic behaviour in medical school has also been associated with subsequent disciplinary action by a state medical board. Papadakis et al. reported a case-control study of all graduates from a single medical school who were subsequently disciplined by a state medical board.5 Ninety-five percent of the disciplinary actions were for deficiencies in professionalism; the prevalence of concerning comments in medical school files was 38% in the disciplined physicians and 19% in controls. Papadakis et al. then identified the specific types of inappropriate behaviour in medical school that were most predictive of disciplinary action against practicing physicians with unprofessional behaviour.6 Disciplinary action by a medical board was strongly associated with evidence of severe irresponsibility and severely diminished capacity for self-improvement. Disciplinary action by a medical board was also associated with low scores on the Medical College Admission Test and poor grades in the first two years of medical school, but the association with these variables was less strong than that with unprofessional behaviour while in medical school. Papadakis et al. then reviewed state licensing board disciplinary actions against 66,171 physicians who entered United States internal medicine residency training programs from 1990 to 2000 to determine whether behaviour during residency also predicted the likelihood of future disciplinary actions against practicing physicians.7 A low professionalism rating on the resident’s annual in-training evaluation summary predicted an increased risk for disciplinary action, and a high performance on the American Board of Internal Medicine certification examination predicted a decreased risk for disciplinary action.

Screening medical school applicants for behaviour patterns that may predispose them to unprofessional behaviours during training and practice reveal that applicants who come to future discipline for behaviour often manifest such patterns as students. Physicians who behave in an unprofessional manner in advanced training or practice were more likely to have exhibited problem behaviours in medical school than control comparators who did not subsequently demonstrate such behaviours. Finally, poor performance on behaviour and cognitive assessments during residency are associated with a greater risk for eventual disciplinary actions by regulatory authorities at every point on a performance continuum.

Physician behaviour patterns and patient complaints and litigation

Hickson et al. reviewed patient complaints about physicians in a medical centre’s hospital and outpatient clinics to study the association between complaints about physician behaviour and physician risk management experiences.8 Both expressions of patient dissatisfaction and surgical specialty were significantly related to risk management experiences. This was true regarding the number of files opened (complaints received), complaints involving expenditures, and complaints involving subsequent lawsuits. Adamson et al. identified communication characteristics among orthopedic surgeons and related them to their number of malpractice lawsuits and the amount paid to settle those claims.9 Physicians who had better rapport with their patients, took more time to explain issues to their patients, and were more available to respond to their patients’ enquiries experienced fewer malpractice lawsuits. The most significant correlation was found in time spent with the patient, i.e., as the time spent increased, the number of lawsuits decreased correspondingly. Ambady et al. investigated the relationship between judgements of surgeons’ voice tone and their malpractice claims history.10 Compared with surgeons with no claims, assessors correctly identified surgeons with previous claims by rating the higher dominance and lower concern for the patient revealed in the surgeon’s tone of voice.

Sloan et al. reported that obstetricians could be divided into three groups based on malpractice claims: physicians with no claims, those with an occasional claim, and those with high claims.11 Bovberg and Petronis conducted a follow-up study and reported that obstetricians with frequent past claims remained at higher risk for future claims.12 There was no evidence that physicians with a high number of claims provided care to patients who were lawsuit prone or that they were less technically skilled or knowledgeable than their colleagues with few claims.13-15 However, there was evidence of differences in physicians’ interpersonal skills, with patients expressing greater dissatisfaction with the communication experiences while under the care of the obstetricians with a high number of claims.16

Physicians who behave in an unprofessional manner towards their patients are more likely to elicit complaints from those patients related to their clinical practices and their interactions. When an unexpected outcome occurs, the feelings arising out of the event are superimposed on an existing physician/patient relationship. If the prior relationship has been characterized by the patient’s bad feelings towards the physician, these may be augmented by the emotions arising out of a poor clinical outcome or even a perceived poor experience in the absence of an adverse outcome. Physicians who are targets of multiple patient complaints or who are subject to a disproportionately high number of lawsuits compared with their peers are also more likely to demonstrate problem patterns of behaviour.

The link between unprofessional behaviour and patient safety

Rosenstein et al. surveyed hospital-based physicians, nurses, and administrators to assess the significance of disruptive behaviours and their perceived effect on communication, collaboration, and patient care.17 The majority of respondents reported that they had witnessed disruptive behaviour in physicians (77% of respondents) and nurses (65% of respondents), and 67% perceived that disruptive behaviours were linked to adverse patient events and outcomes. Rosenstein and O’Daniel reported that disruptive behaviours were a common occurrence in the perioperative setting. Attending surgeons were the most common offenders, but the behaviours were not uncommon in anesthesiologists as well.18 Such behaviours increased levels of stress and frustration, impaired concentration, impeded communication flow, and adversely affected staff relationships and team collaboration. These events were perceived to increase the likelihood of errors and adverse events and to compromise patient safety and quality of care. Mazzocco et al. reported that patients of surgical teams with good teamwork profiles experienced better outcomes than those with poor profiles.19 Observers used a standardized instrument to assess team behaviours, and a retrospective chart review was carried out to measure 30-day outcomes. When composite measures of teamwork were exhibited more frequently, patients had decreased odds of complications or death, even after adjusting for the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ score.

Inappropriate physician behaviour is associated with adverse outcomes in patients. These behaviours occur in the perioperative setting, and anesthesiologists have been identified as one of the groups commonly displaying such behaviours.

Behaviour issues and resident performance and health

Rhoton analysed the performance records of 71 anesthesiology residents to assess the relationship between unprofessional behaviour and overall performance during 24 months of clinical activity.20 Fifteen residents (21%) received comments about unprofessional behaviour, predominantly involving unacceptable behaviour, abdication of responsibility, and fabrications. These same residents demonstrated problems regarding perceived conscientiousness, composure, critical incidents, efficiency/organization, taking instruction, and knowledge. Conversely, there were no problems with unprofessional behaviour in the records of 21 residents whose evaluation scores for overall performance were excellent. The results reveal a pattern of suboptimal performance associated with unprofessional behaviour, and once again, they suggest that clinical excellence and unprofessional behaviour rarely coexist despite the commonly held beliefs to the contrary.

Reed et al. reviewed the assessments of 148 first-year internal medicine residents to identify behaviours that distinguish highly professional residents from their peers.21 Highly professional residents (those who scored ≥ 80th percentile on observation-based assessments) achieved higher median scores on the in-training examinations and clinical evaluation exercises, and they completed a greater percentage of required evaluations compared with residents with lower professionalism scores. Six of the eight residents who received a warning or were placed on probation had total professionalism scores in the bottom 20% of residents. There was a correlation between observation-based assessments of professionalism and favourable evaluations of residents’ knowledge and clinical skills. Rowley et al. tracked surgery residents during a 50-month period and evaluated them on objective criteria, such as clinical abilities and performance, and more subjective qualities, including ethical standards and interpersonal skills; they found a correlation between the objective and subjective criteria.22

Residents who demonstrate high levels of professionalism also scored significantly higher on every dimension of skills and knowledge performance assessments. This convergence suggested that those qualities comprising professionalism are important elements in the determination of the residents’ overall clinical performance. Baldwin et al. surveyed 857 second-year residents concerning their own personal observations of unethical and unprofessional conduct during their first postgraduate year.23 Many of the residents reported observing colleagues behaving in an unprofessional manner, and there was an inverse correlation between the residents’ observations of unethical and unprofessional conduct and their overall satisfaction with their training. Thus, residents who demonstrate unprofessional behaviour not only often function at a lower clinical level than their more professional peers but their behaviour is also more likely to have a negative impact on both the environment and their relationships with their colleagues.

The impact of problem behaviour in the workplace

Rosenstein and O’Daniel examined disruptive behaviour in both physicians and nurses and the effects of such behaviours on both care providers in the clinical environment and clinical outcomes.24 Most respondents perceived disruptive behaviour as having a negative impact on both nurses and physicians in relation to stress, frustration, concentration, communication, collaboration, information transfer, and workplace relationships. Even more disturbing were the respondents’ perceptions that disruptive behaviour increased medical errors, adverse events, and patient mortality, and decreased patient safety, quality of care, and patient satisfaction. Rosenstein also reported that daily interactions between nurses and physicians strongly influence nurses’ morale; there was a direct link between disruptive physician behaviour and nurse satisfaction and retention.25

The educational curriculum: the official, the informal, and the hidden

The curriculum for any educational program is generally accepted to be the anthology of course content offered to students enrolled in the field of study. The curriculum specifies the topics that must be understood and the level required to meet a particular standard. In medicine, this standard is generally acknowledged to be competent practice. Additionally, in medical training, the concept of the curriculum becomes more expansive than this basic construct as the student moves from the pre-clinical period and enters the clinical realm. At this juncture, the curriculum encompasses the entire scope of training and experience to which the student is exposed within both the classroom and the clinical environment. Medical students and residents receive instruction via at least two curricula, i.e., the official (stated) curriculum and a more informal curriculum. The official curriculum is structured and delivered by lectures, discussion groups, and rounds, and it is increasingly based on facts and tested. The informal curriculum is delivered during the day-to-day interactions of the trainees with their mentors, and it is more personal and less structured. In the latter forum, opportunities are presented for the exchange of ideas, opinions, and experiences, and the environmental values, norms, and expectations are taught. Professional values are more likely taught during the more casual exchanges of the informal curriculum than during the structured curriculum.26 Although staff are involved in a considerable proportion of informal professional teaching experiences, senior residents also provide a large volume of teaching to more junior trainees and are responsible for considerable values teaching.

An element of the informal curriculum involves staff or senior trainees conveying “messages” to students or junior colleagues regarding behaviours that might run counter to the objectives of the official curriculum (i.e., behaviours that could be labelled inappropriate, unprofessional, or disruptive, and may be isolated or repetitive). There is a fundamental “message” conveyed in this hidden curriculum, i.e., questionable behaviours are not unacceptable, at least in the eyes of the staff displaying them and the student observing them. That being said, Hafferty recognized that there is potential within this latter curriculum to model behaviours that are highly desirable—not all attributes of the hidden curriculum are negative.27 However, the problem with modelling negative attributes lies in what we teach students by our own actions and inactions each day, and these lessons may run counter to the ideals espoused in the formal curriculum. Students may incorporate attitudes and demonstrate behaviours that are diametrically opposed to those that the mentors intended to instil, yet they are, in fact, modelled on the observations of their teachers’ behaviours.

Faculty may model professionally undesirable behaviours to trainees; they may also demonstrate reluctance to intervene when students or residents themselves display problematic behaviours. Burack et al. performed a prospective observational study to describe the response of attending physicians to learners’ behaviours that indicate negative attitudes toward patients.28 The attending staff readily identified three categories of potentially problematic behaviours (i.e., showing disrespect for patients, cutting corners, and outright hostility or rudeness), but they were rarely observed to respond to these behaviours. When the attending staff did respond, they favoured passive nonverbal gestures. Verbal responses were applied infrequently and included techniques that avoided blaming learners for their behaviour. Attending physicians did not explicitly discuss trainees’ attitudes, refer to moral or professional norms, or call attention to the behaviours, and they rarely gave behaviour-specific feedback. The reasons for not responding included empathy for learner stress, the perception that corrective feedback would likely be ineffective, and lack of professional reward for giving negative feedback. Due to this uncertainty, attending physicians were reluctant to respond to perceived disrespect, uncaring attitudes, or hostility toward patients by members of their own medical teams. They tended to respond in ways that avoided moral language, did not address underlying attitudes, and left room for face-saving reinterpretations. Although these oblique techniques were sympathetically motivated, trainees may misinterpret or fail to take notice of such feedback, and they may not be prompted to alter their behaviour. A consequence of this failed feedback is persistence of problem attitudes on the part of some trainees towards patients.

Gillespie et al. surveyed senior residents to assess their perceptions of both their professional competence and the professionalism of their learning environment.29 Residents reported feeling most competent in being accountable and in demonstrating respect towards patients, although some residents reported having difficulty being sensitive towards patients. The most frequently witnessed lapse in professionalism in the learning environment was disrespectful behaviour; several serious lapses were witnessed by a small number of residents, and accountability and consequences for the behaviour were uncertain.

Strategies for teaching and modelling professional behaviour

There is limited evidence regarding the most effective ways to promote the development of professional behaviour in medical trainees. However, there is an emerging consensus that role modelling of desired behaviours by staff physicians is an important mechanism to demonstrate professional behaviour to trainees. Passi et al. identified three characteristics of good role models, i.e., clinical competence, teaching skills, and personal qualities.30 Almost certainly, trainees recognized as excellent role models those physicians who, in addition to providing good clinical care, took the time to facilitate feedback and made a conscious effort to articulate what they were modelling. This is a demanding expectation, and there are issues with consistently modelling such behaviours. Bryden et al. recruited clinical faculty involved in medical education to explore their knowledge and attitudes regarding the teaching and evaluation of professionalism.31 All faculty expressed the perception that role modelling was the dominant teaching tool in this area. However, they acknowledged that the process of teaching and evaluating professionalism posed challenges for them—it identified their own lapses in professionalism and their sense of powerlessness. Failure to address these lapses with one another was identified as the single greatest barrier to teaching professionalism.

Consistently behaving in a highly professional manner is a challenging task in an optimal environment, and the challenge is augmented under stressful circumstances. Edelstein et al. reported that many of the problems of professionalism observed in an operating room arose during periods of heightened stress.32 Many faculty and residents were aware that the behaviour of individuals was adversely affected primarily when patient management became complicated. Lingard et al. reported that tensions relating to a relatively small number of themes (e.g., perceptions of efficiency, safety, resources, and roles) often arose in the operating room.33 Surgical trainees were involved in more than one-third of these high-tension events, and they tended to respond in one of two ways, i.e., by mimicking staff behaviour (even when inappropriate) or by withdrawing from the communication. Withdrawal was the most common response, but both responses were considered to have negative implications for team relations.

Consistently behaving as model citizens in an environment that is populated with multiple stressors is, and always has been, a challenging expectation for both faculty and students. However, we need to acknowledge that our workplace has changed, and now there is limited tolerance for some types of behaviour which were prevalent in the past, and there is zero tolerance for others. There is evidence of values being conveyed from staff to student that do not support the development of professional behaviour, and many of these are unintended and even unrecognized. We must also emphasize the importance of appropriate role modelling for professionalism in faculty, and we need to ensure there is support for faculty development programs to foster such advancement. There must be appropriate support for remediation for faculty and residents who occasionally depart from acceptable norms of behaviour. More assertive interventions may be required for those who persistently behave in an unprofessional manner as these behaviours are associated with compromised patient safety, adverse outcomes, and a negative impact on the workplace environment.

The way forward: promoting structured teaching of professionalism

To gain insight into the current status of professionalism education in Canadian anesthesia training programs, we surveyed program directors via E-mail. We queried them regarding the training and evaluation of resident professionalism, the processes employed to investigate and set consequences for allegations of unprofessional resident or staff behaviour, and the availability of faculty support for professionalism teaching and evaluation. The survey was sent to 17 directors and 11 (64.7%) responded (Table 2). The CanMEDS roles1 are being applied in most programs to assess residents’ non-clinical skills, including professional behaviours, and professionalism is formally addressed during the teaching curriculum of most programs. Most programs (91%) are using daily evaluation cards for resident assessment. When concerns about resident or faculty professional behaviour arise, most directors indicated that the programs include a defined mechanism to investigate and respond to the allegation at the level of the program, the university, or, in some instances, both. Four directors (36%) indicated they were aware of faculty development programs that provide continuing professional development to allow faculty to develop strategies and tools for the teaching and evaluation of professionalism among residents. In some instances, these programs may exist and the directors are unaware of their existence; conversely, it may be true that such programs do not exist in the majority of Canadian centres.

The responses indicate that the majority of Canadian training programs recognize the importance of formal professionalism training and have implemented such training. The CanMEDS structure appears to predominate in terms of an objective benchmark against which to measure behaviours. As well, most programs appear to have developed mechanisms to evaluate and respond to allegations of unprofessional behaviour among both residents and staff. However, there seems to be room in the programs for improvement in organized faculty development to ensure that faculty members possess strategies for the teaching and evaluation of professionalism among residents. This is particularly important because faculty readily recognize and acknowledge deficiencies in this area of instruction and evaluation of residents. Since strategies are lacking, faculty are often uncertain how to intervene effectively when unprofessional behaviour is evident.

A framework for defining expectations for resident and physician behaviour

At the outset, it is necessary to define the expectations for residents’ professional behaviour if they are to be subsequently evaluated on their behaviour. It is beyond the scope of this document to deal with the expectations for clinical achievement as this paper deals primarily with professional behaviours. It is also apparent that not all training programs will have a consistent approach to the teaching and evaluation of professional behaviour. This may be due to a range of considerations, including, but not limited to, philosophical differences between programs and resource limitations in some. However, there should be consistency in terms of the fundamental expectations regarding professionalism. Institutions where residents receive their basic medical education may not place the same emphasis on professionalism, and this issue should be considered when selecting resident candidates for the training program. Thus, once program expectations for resident behaviour have been determined, efforts should be made to select candidates who already manifest behaviour patterns consistent with program expectations.

The Canadian Medical Association’s CMA Code of Ethics (http://policybase.cma.ca/PolicyPDF/PD04-06.pdf) provides a reasonable framework on which to structure the general expectations for resident behaviour in Canadian training programs.34 The first three directives listed in the Code’s “Fundamental Responsibilities” emphasize the need to consider the well-being of the patient first, to treat the patient with dignity and respect, and to provide for appropriate care for the patient. The next three directives reflect the expectation that physicians will practise medicine competently and with integrity. The final fundamental responsibilities direct that physicians contribute to the development of the medical profession, advocate on behalf of the profession or the public, and promote their own health and well-being. Although a number of other directives related to behaviour are distributed through the Code, the bulk of further relevant directives are grouped under “Responsibilities to the Profession”, and many are echoed in the CanMEDS roles developed by the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada.

The CanMEDS 2005 document—the update to Skills for the New Millennium published in 1996—was created by the Royal College’s Office of Education as a resource to support medical education, physician competence, and quality care.1,35 Both documents reflect the College’s attempt to establish a competency-based framework to describe the principal generic abilities of physicians oriented toward optimal health and health care outcomes. The changing societal role of physicians requires training programs to teach future physician specialists the multifaceted responsibilities they will be expected to perform in their professional duties. The CanMEDS roles comprise medical competencies organized thematically around “meta-competencies” and positioned on the central integral role of the “medical expert”. Although several of these meta-competencies reflect more traditional expectations for physicians, such as “scholar” and “manager”, others reflect competencies which, though desired in a physician, were arguably not formally taught to trainees in the past, i.e., “communicator”, “collaborator”, “health advocate”, and “professional”. Interestingly, these later competencies are increasingly recognized as core to physician behaviour now characterized as highly professional. In our survey of program directors, all seemed to recognize implicitly the value of the CanMEDS structure as it had been integrated into the process of resident evaluation.

If the CMA Code of Ethics and roles in the Royal College’s CanMEDS 2005 Physician Competency Framework are the yin of professional behaviour, the regulatory authorities’ guides to professional behaviour are the yang. Many colleges include statements on their websites regarding expectations for professional behaviour and provide examples of exceptions to these expectations. In particular, the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario and the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Alberta put forward particularly complete and detailed packages.36,37 These Guides set out expectations for professional behaviour to a limited degree, they are mainly devoted to identifying unacceptable behaviour in the medical care environment. Although this behaviour is popularly labelled as “disruptive”, this label implies a behaviour that is overtly and even dramatically offensive (e.g., the screaming swearing surgical specialist throwing hammers at operating room nurses). In fact, many of these problem behaviours are far more subtle yet consistent in their ability to compromise patient care, subvert interprofessional relationships, interfere with teaching trainees, and ultimately, to disrupt the environment and the system of care. The Guides further detail the need for an organized approach to respond to instances of inappropriate behaviour once expectations for behaviour in the environment have been clearly enunciated. There is a need to ensure that: appropriate mechanisms exist for reporting unacceptable behaviour; misbehaviour is documented and the set of facts describing the event are accurate; a potential for the non-adversarial resolution of identified issues is present; educational programs designed to achieve behavioural change are accessible; and progressive and proportionate sanctions exist and are implemented when inappropriate behaviour is not modified despite repeated interventions. These processes must be integrated into a system which ensures that retribution against victims is not permitted and processes are fundamentally sound and fair.

Ensuring behavioural expectations are met by residents and faculty

The first step to ensure that behavioural expectations are met is to shape an environment in which the desired behaviours become the prevalent and preferred styles of the majority. It is a flawed exercise to construct and enforce behavioural guidelines for residents alone exclusive of faculty. Faculty behaviours deemed acceptable because they are tolerated, even if wholly inappropriate and undesirable, will be modelled by some resident observers, thus perpetuating these behaviours. In this case, the credibility of such a system is highly compromised, and the desired outcomes are less likely to be achieved. It is necessary to communicate expectations explicitly to achieve adherence to expectations from all members of the department. This step is challenging and often neglected. However, this provides the department with the opportunity to convey its performance expectations clearly and succinctly and to ensure that individual members (particularly those whose behaviour may have been problematic in the past) accept the expectations in a convincing and sincere manner. At this early stage, it is also necessary to outline the process should a member of the department exhibit behaviour contrary to expectations.

The next step is to recruit resident and staff physicians who are more likely, based on past behaviour, to exhibit desired behaviours once they enter the environment. At the residency program level, this calls for identifying among the candidates risk attributes that are associated with inappropriate and unprofessional behaviour. This does not mean that excessively rigid behavioural criteria need be applied to all candidates being considered for residency positions. It does mean that of risk attributes be recognized at the outset so that a decision can be made as to how best to deal with this additional demand for education and training. At the faculty level, this assessment can be carried out when conferring credentials and privileges; the best way to address behavioural issues is at the entrance door, recognizing that a history of behavioural issues is a potent predictor of future problems. A physician may have left a previous work environment where truly everyone else’s perceptions were wrong and he/she was right, but this scenario is unlikely, and such a physician is just as unlikely to find kindred spirits in the new environment. Past difficulties will recur if behaviours do not change, and new colleagues in the receiving centre will soon develop considerable empathy with their new member’s former colleagues. Once the department recommends membership and privileges on behalf of a colleague, it should deal with performance issues through the peer review process.

In order to assess the behaviour of staff (residents and faculty) fairly, it is necessary to articulate performance expectations clearly and to ensure that they are well disseminated in advance of any assessment. Ill-defined benchmarks or arbitrary indicators provide little explicit direction regarding behavioural expectations. “We’ll know bad behaviour when we see it”, is an unacceptable strategy for setting behavioural benchmarks. Annual or periodic reviews and in-training evaluations are mechanisms to measure performance against expectations, and these methods can be employed to deal with minor deviations from expected behaviour. Obviously, such reviews are not suitable for wholly inappropriate or allegedly egregious behaviour which demands immediate review and intervention if allegations of unprofessional behaviour are confirmed. However, the ongoing and periodic review process among residents and faculty may effectively reinforce that there is serious intent to foster an environment where highly professional behaviour is both the norm and the expectation. During these reviews, explicit feedback based on gathered data is necessary. Most conscientious physicians are more likely to modify their behaviour and improve their performance—thus obviating the need for any leadership intervention— if it can be demonstrated to them that “whereas most of their colleagues are here on the behaviour grid, you’re over here”.

There must be a commitment to manage resident or staff physician behaviour that is outside of articulated expectations, especially if it is repetitive. This is challenging, as it is recognized that many unacceptable behaviours are ignored by observers either to avoid conflict or because they are uncertain how best to respond. However, this could be the final opportunity to assist and support a practitioner in making the performance improvements necessary to avoid corrective action which could result in lost opportunities for training, promotion, or even the maintenance of privileges. This process could begin with collegial interventions by colleagues or mentoring by the program director or selected staff tutors. If the behaviour persists despite such informal mechanisms, mandatory improvement plans should then be established and implemented. All parties are well served by a clear fair and well-documented process. Documentation increases the likelihood that the set of facts will be perceived as accurate and not subject to challenge and that the defined process was clearly followed. Most physicians do not receive instruction in management protocol as part of their education, and those who accept leadership roles may require training to structure and implement these interventions, as the physicians who require them are often adept at avoiding, negating, or subverting the need to modify their behaviour.

Finally and rarely, it might be necessary to invoke the ultimate sanction. If behaviour has repeatedly been documented to be outside defined expectations and the resident has been resistant to guidance and intervention, sanctions and dismissal may be necessary. Obviously, such corrective actions would also apply to physicians manifesting such behaviours, and this approach can be implemented incrementally. Unfortunately for the hardened and chronic offenders, severe sanctions may be the only interventions capable of getting their attention.

It was not the intent of this review to provide readers with direction for the management of colleagues displaying questionable behaviour but rather to emphasize the need to develop mechanisms to do so effectively in their own environments. However, those readers seeking a more detailed review of that aspect of the topic, including case studies, are referred to the American College of Physician Executives publication, Managing Disruptive Physician Behavior (http://net.acpe.org/resources/publications/OnTargetDisruptivePhysician.pdf) and, in particular, Kent Neff’s chapter (Chapter 4).38

Conclusions

The recognition that people who persistently behave in an unprofessional disrespectful obstructive or disruptive manner have an unfavourable impact on the environment in which they work is not unique to health care. In an editorial published in the Harvard Business Review as one of the “Breakthrough Ideas for 2004” and entitled “More Trouble Than They’re Worth”, Robert Sutton, Professor of Management Science and Engineering at Stanford University, outlined the damage that such behaviours cause in the environments in which they occur.39 Sutton opined that organizations which take action against such behaviours are making statements about their values, and these statements send strong positive messages to the members of the organization. The response provoked by the editorial was such that Sutton later followed up with a book with the mildly obscene title, “The No Asshole Rule: Building a Civilized Workplace and Surviving One That Isn’t”, in which he further detailed the destructive impact of such behaviours on the health and productivity of a workplace and the value in intervening to correct such behaviours.40

Troubling behaviours in the health care environment are not pervasive nor are they rare; their negative impacts have now been well documented. They are associated with compromised patient safety and a higher incidence of adverse outcomes. Additionally, unprofessional behaviours are also correlated with increased patient dissatisfaction, complaints from patients, regulatory authority discipline, and medical litigation events. Health care workers, including physicians, who are the targets of such behaviours, and even those who merely witness them, are more likely to report dissatisfaction with their work environment and training programs. Finally, retention of nurses by hospitals and institutions is decreased in care environments where unprofessional behaviours are not addressed vigorously.

The issue is not about being nice for the sake of being nice. It is recognized that the quality of care is enhanced when physician leaders set expectations for professional behaviours in the care environment, when they encourage these behaviours, and when they intervene consistently when these expectations are not met. Not surprisingly, there is also evidence that these environments are healthier for the people working in them as well as for those receiving care.

There is much work yet to be done. Despite there being less tolerance for behaviour once accepted and zero tolerance for behaviour which should never have been tolerated, in the vast majority of instances, there remains a clear role for behaviour modification and remediation efforts to assist residents and physicians who exhibit unprofessional behaviour. It is essential to develop management protocols to identify problem patterns of behaviour, to document such occurrences accurately, and to intervene early and meaningfully to address the problem behaviour. The process should provide supportive guidance to allow for continuing professional development at all physician levels. These guiding principles should apply to medical students, residents, and physicians in practice, and ideally, they should be managed by peers and colleagues. Failure to establish such guidelines could result in sanctions being applied more frequently by higher level authorities who are determined to terminate undesirable behaviours and may be less concerned about the impact on the physicians themselves.

Notes

ACGME Outcome Project: Advancing education in medical pro-fessionalism. Chicago IL, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, 2004. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/outcome/implement/Profm_resource.pdf (accessed May, 2011).

References

Frank JR (Ed). The CanMEDS 2005 Physician Competency Framework. Better Standards. Better Physicians. Better Care. 2005. Ottawa. The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. Available from URL: http://meds.queensu.ca/medicine/obgyn/pdf/CanMEDS2005.booklet.pdf (accessed August 2011)

Knights JA, Kennedy BJ. Medical school selection: screening for dysfunctional tendencies. Med Educ 2006; 40: 1058-64.

Stern DT, Frohna AZ, Gruppen LD. The prediction of professional behaviour. Med Educ 2005; 39: 75-82.

Brenner AM, Mathai S, Jain S, Mohl PC. Can we predict “problem residents”? Acad Med 2010; 85: 1147-51.

Papadakis MA, Hodgson CS, Teherani A, Kohatsu ND. Unprofessional behavior in medical school is associated with subsequent disciplinary action by a state medical board. Acad Med 2004; 79: 244-9.

Papadakis MA, Teherani A, Banach MA, et al. Disciplinary action by medical boards and prior behavior in medical school. N Engl J Med 2005; 353: 2673-82.

Papadakis MA, Arnold GK, Blank LL, Holmboe ES, Lipner RS. Performance during internal medicine residency training and subsequent disciplinary action by state licensing boards. Ann Intern Med 2008; 148: 869-76.

Hickson GB, Federspiel CF, Blackford J, et al. Patient complaints and malpractice risk in a regional healthcare center. South Med J 2007; 100: 791-6.

Adamson TE, Bunch WH, Baldwin DC Jr, Oppenberg A. The virtuous orthopaedist has fewer malpractice suits. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2000; 378: 104-9.

Ambady N, LaPlante D, Nguyen T, Rosenthal R, Chaumeton N, Levinson W. Surgeons’ tone of voice: A clue to malpractice history. Surgery 2002; 132: 5-9.

Sloan FA, Mergenhagen PM, Burfield B, Bovbjerg RR, Hassan M. Medical malpractice experience of physicians. Predictable or haphazard? JAMA 1989; 262: 3291-7.

Bovberg RR, Petronis KR. The relationship between physicians’ malpractice claims history and later claims. Does the past predict the future? JAMA 1994; 272: 1421-6.

Burstin HR, Johnson WG, Lipsitz SR, Brennan TA. Do the poor sue more? A case-control study of malpractice claims and socioeconomic status. JAMA 1993; 270: 1697-701.

Sloan FA. The injuries, antecedents, and consequences. In: Sloan FA (Ed). Suing for Medical Malpractice. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1993: 31-50.

Entman SS, Glass CA, Hickson GB, Githens PP, Whetten-Goldstein K, Sloan FA. The relationship between malpractice claims history and subsequent obstetric care. JAMA 1994; 272: 1588-91.

Hickson GB, Clayton EW, Entman SS, et al. Obstetricians’ prior malpractice experience and patients’ satisfaction with care. JAMA 1994; 272: 1583-7.

Rosenstein AH, O’Daniel M. Survey of the impact of disruptive behaviors and communication defects on patient safety. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2008; 34: 464-71.

Rosenstein AH, O’Daniel M. Impact and implications of disruptive behavior in the perioperative arena. J Am Coll Surg 2006; 203: 96-105.

Mazzocco K, Petitti DB, Fong KT, et al. Surgical team behaviors and patient outcomes. Am J Surg 2009; 197: 678-85.

Rhoton MF. Professionalism and clinical excellence among anesthesiology residents. Acad Med 1994; 69: 313-5.

Reed DA, West CP, Mueller PS, Ficalora RD. Behaviors of highly professional resident physicians. JAMA 2008; 300: 1326-33.

Rowley BD, Baldwin DC Jr, Bay RC, Cannula M. Can professional values be taught? A look at residency training. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2000; 378: 110-4.

Baldwin DC Jr, Daugherty SR, Rowley BD. Unethical and unprofessional conduct observed by residents during their first year of training. Acad Med 1998; 73: 1195-200.

Rosenstein AH, O’Daniel M. Disruptive behavior and clinical outcomes: perceptions of nurses and physicians. Am J Nurs 2005; 105: 54-64.

Rosenstein AH. Nurse-physician relationships: impact on nurse satisfaction and retention. Am J Nurs 2002; 102: 26-34.

Stern DT. In search of the informal curriculum: when and where professional values are taught. Acad Med 1998; 73: S28-30.

Hafferty FW. Beyond curriculum reform: confronting medicine’s hidden curriculum. Acad Med 1998; 73: 403-7.

Burack JH, Irby DM, Carline JD, Root RK, Larson EB. Teaching compassion and respect. Attending physicians’ responses to problematic behaviors. J Gen Intern Med 1999; 14: 49-55.

Gillespie C, Paik S, Ark T, Zabar S, Kalet A. Residents’ perceptions of their own professionalism and the professionalism of their learning environment. J Grad Med Educ 2009; 1: 208-15.

Passi V, Doug M, Peile E, Thistlethwaite J, Johnson N. Developing medical professionalism in future doctors: a systematic review. Int J Med Educ 2010; 1: 19-29.

Bryden P, Ginsburg S, Kurabi B, Ahmed N. Professing professionalism: are we our own worst enemy? Faculty members’ experiences of teaching and evaluating professionalism in medical education at one school. Acad Med 2010; 85: 1025-34.

Edelstein SB, Stevenson JM, Broad K. Teaching professionalism during anesthesiology training. J Clin Anesth 2005; 17: 392-8.

Lingard L, Reznick R, Espin S, Regehr G, DeVito I. Team communications in the operating room: talk patterns, sites of tension, and implications for novices. Acad Med 2002; 77: 232-7.

Canadian Medical Association. CMA Code of Ethics (update 2004). Available from URL: http://policybase.cma.ca/PolicyPDF/PD04-06.pdf (accessed June 2011).

The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. Skills for the new millenium: report of the societal needs working group. CanMEDS 200 Project. September 1996. Ottawa, Canada. The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada’s Canadian Medical Education directions for Specialists 2000 Projet. Available from URL: http://meds.queensu.ca/medicine/obgyn/pdf/CanMEDS2000.pdf (accessed August 2011).

College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario. Ontario Hospital Association. A Guidebook for Managing Disruptive Physician Behavior. April 2008. Toronto: Available from URL: http://www.cpso.on.ca/uploadedFiles/policies/guidelines/office/Disruptive%20Behaviour%20Guidebook.pdf (accessed August 2011).

College of Physicians and Surgeons of Alberta. Managing Disruptive Behavior in the Healthcare Workplace. Guidance Document, Fall 2010. Edmonton: Available from URL: http://www.cpsa.ab.ca/Libraries/Res/MDB_guidance_document_toolkit_for_web.pdf (accessed August 2011).

Neff KE. Understanding and managing physicians with disruptive behaviour. American College of Physician Executives. On Target, Managing Disruptive Physician Behavior. Tampa, FL. Available from URL: www.acpe.org (accessed August 2011).

Sutton R. More trouble than they’re worth. Harv Bus Rev 2004; 82: 19-20.

Sutton RI. The No Asshole Rule: Building a Civilized Workplace and Surviving One That Isn’t Business Plus; 2007.

Funding statement

Support for this work was drawn solely from the internal resources of the Department of Anesthesiology of the University of Ottawa.

Disclaimer

The authors declare that they have no affiliations which may be perceived to represent a conflict of interest relating to any items or issues discussed in this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Brief survey regarding teaching and assessment of professionalism

Appendix: Brief survey regarding teaching and assessment of professionalism

-

1.

Does your training program use evaluation cards for resident assessment?

-

a.

If yes, are they done daily____, at the end of the rotation____ or other____?

-

a.

-

2.

Is professional behaviour (CanMEDS 2005) identified as a specific item when faculty are providing resident assessment?

-

3.

In the event of an allegation of unprofessional behaviour by as resident, is there a defined mechanism as to how to investigate the allegation and deal with the resident?

-

a.

If yes, is it at the level of the Program____, University____, or other____?

-

a.

-

4.

Is there formal teaching of aspects of professionalism during anesthesia residency in your program?

-

a.

If yes, does this involve lectures____, group discussions____, or other____?

-

a.

-

5.

In the event of an allegation of unprofessional behaviour on the part of a faculty member in regards to resident(s), is there a defined mechanism as to how to investigate the allegation and deal with the faculty member?

-

a.

If yes, is it at the level of the Program____, University____, or other____?

-

a.

-

6.

Are faculty provided continuing professional development to allow them to develop strategies and tools to allow for the evaluation of professionalism among the residents?

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bahaziq, W., Crosby, E. Physician professional behaviour affects outcomes: A framework for teaching professionalism during anesthesia residency. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 58, 1039–1050 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-011-9579-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-011-9579-2