Abstract

Purpose

Postoperative nausea and vomiting are among the most common and distressing side effects of general anesthesia. Supplemental intraoperative 80% oxygen reduces postoperative nausea and vomiting following open and laparoscopic abdominal surgery. However, this benefit has not been observed in other patient populations. We undertook this study to evaluate the effect of 80% supplemental intraoperative oxygen on the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting following ambulatory surgery for laparoscopic tubal ligation.

Methods

Following Research Ethics Board approval, 304 subjects were enrolled into one of two arms of a randomized prospective controlled study. The intervention group (n = 147) breathed 80% oxygen and the control group (n = 145) breathed routine 30% oxygen (balance medical air) while both groups were receiving a standardized general anesthetic. Nausea was assessed as: none, mild, moderate, or severe; vomiting was any emetic episode or retching. Any assessment either greater than none (nausea) or greater than zero (vomiting) was considered positive.

Results

The incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting up to 24 hr following surgery was 69% in the 80% oxygen intervention group and 65% in the 30% oxygen control group (P = 0.62). There were no differences in nausea alone, vomiting, or antiemetic use in the postoperative anesthetic care unit or at any time (pre- or post-discharge) up to 24 hr after surgery.

Conclusions

This trial of 304 women did not demonstrate that administering intraoperative supplemental 80% oxygen during ambulatory surgery for laparoscopic tubal ligation prevented postoperative nausea or vomiting during the initial postoperative 24 hr compared with women who received routine 30% oxygen.

Résumé

Objectif

Les nausées et vomissements postopératoires sont parmi les effets secondaires les plus courants et pénibles de l’anesthésie générale. L’oxygène peropératoire supplémentaire à 80 % réduit les nausées et vomissements postopératoires après les chirurgies abdominales ouvertes et par laparoscopie. Toutefois, ce bienfait n’a pas été observé dans d’autres populations de patients. Nous avons entrepris cette étude afin d’évaluer l’effet d’oxygène peropératoire supplémentaire à 80 % sur l’incidence des nausées et vomissements postopératoires après une chirurgie ambulatoire de ligature tubaire par laparoscopie.

Méthode

Après avoir reçu l’approbation du Comité d’éthique de la recherche, 304 patientes ont été enrôlées dans deux groupes d’une étude prospective randomisée et contrôlée. Le groupe intervention (n = 147) a respiré de l’oxygène à 80 % et le groupe témoin (n = 145) a respiré de l’oxygène normal à 30 % (air médical équilibré), et les deux groupes ont reçu un anesthésique général standardisé. Les nausées ont été évaluées selon l’échelle suivante : aucune, légères, modérées, ou graves; tout épisode émétique ou haut-le-cœur a été considéré comme un vomissement. Toute évaluation rendant des résultats plus élevés que ‘aucune’ (nausées) ou ‘zéro’ (vomissements) a été considérée positive.

Résultats

L’incidence des nausées et vomissements postopératoires jusqu’à 24 heures après la chirurgie était de 69 % dans le groupe intervention (oxygène 80 %) et de 65 % dans le groupe témoin (oxygène 30 %) (P = 0,62). Il n’y a pas eu de différence dans les nausées seules, les vomissements ou le recours à des antiémétiques dans l’unité de soins anesthésiques postopératoires ou en tout temps (avant et après le congé de l’hôpital) durant les premières 24 heures après la chirurgie.

Conclusion

Cette étude portant sur 304 femmes n’a pas démontré que l’administration peropératoire d’oxygène supplémentaire à 80 % pendant une chirurgie ambulatoire de ligature tubaire par laparoscopie a prévenu les nausées et vomissements postopératoires pendant les 24 premières heures par rapport à des patientes recevant de l’oxygène à 30 % utilisé normalement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Nausea and vomiting are among the most common and distressing adverse effects of anesthesia. Surgical patients report that they are more fearful of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) than of postoperative pain.1 Although some anesthesiologists administer pharmacologic prophylactic antiemetics at the time of surgery, there has been limited success with the available therapeutic agents, and PONV remains a significant problem.2 Administration of intraoperative supplemental oxygen has been proposed as a non-pharmacological inexpensive and safe way of addressing PONV.3,4

In 1999, Greif et al. reported that supplemental oxygen reduces the incidence of PONV in patients undergoing open colon resection.3 These investigators later showed that administering supplemental intraoperative 80% oxygen for more than 1 hr in subjects undergoing gynecological laparoscopy reduced PONV by 50% compared with subjects breathing 30% oxygen.4 They hypothesized that the biologic mechanism of supplemental intraoperative oxygen was due to prevention of intestinal ischemia from surgical stress and bowel manipulation during intra-abdominal procedures.

Although these reports were intriguing, more recent studies have shown that administering supplemental intraoperative oxygen does not benefit patients by reducing PONV during abdominal and non-abdominal types of surgery.5–11 The relevance of these findings with respect to gynecological laparoscopic procedures is unclear, since only one of these subsequent studies involved subjects undergoing gynecological laparoscopic procedures6 where the beneficial effects of supplemental oxygen had been previously observed.4

To help elucidate the potential benefit of supplemental intraoperative oxygen in this high-risk population, we hypothesized that administering intraoperative supplemental 80% oxygen, compared with administering 30% oxygen, would reduce the incidence of postoperative nausea and/or reduce vomiting by 50% among women for up to 24 hr following ambulatory laparoscopic gynecological surgery of short (less than 1 hr) duration.

Methods

Following IWK Health Centre Research Ethics approval and individual written informed consent, 304 subjects were enrolled in this prospective randomized double-blind study. Eligible patients included women undergoing ambulatory laparoscopic tubal ligation who were American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) status I or II. Exclusion criteria included the following: request for preoperative benzodiazepines, diabetes, gastroparesis, obesity (Body Mass Index [BMI] > 37), current breastfeeding, nausea/vomiting or antiemetic therapy, current opioid/cannabis use, or known substance abuse within six months of enrolment. Patients were also excluded if they had a previous history of PONV lasting >24 hr where prophylactic antiemetic therapy was indicated or where postoperative admission was required.

Study protocol and blinding

Following endotracheal intubation, patients were allocated to receive routine 30% oxygen or supplemental 80% oxygen along with balanced fresh gas flow, i.e., compressed medical air, Oxygen (O2) 18–23% in Nitrogen (N2) (N2/O2) not nitrous oxide (N2O). Opaque sealed envelopes contained the computer-generated random assignments, and the seal was broken following induction of anesthesia. The attending anesthesiologist was not blinded to group assignment for safety and ethical reasons. Patients, investigators, study personnel making outcome assessments, surgeons, and postanesthesia care unit (PACU) nurses were blinded to group allocation. Cardboard shields positioned over the fresh gas oxygen/air flow meters ensured blinding of the intraoperative surgical and nursing teams.

Patients did not receive preoperative sedation. General anesthesia was administered according to a standardized protocol. Following preoxygenation with 100% oxygen for 2 min, anesthesia was induced with midazolam 0.02 mg · kg−1 iv, propofol 2.0–3.5 mg · kg−1 iv, succinylcholine 1.5 mg · kg−1 and/or rocuronium 0.5 mg · kg−1 iv, and fentanyl citrate 1–3 μg · kg−1 iv. Following endotracheal intubation, anesthesia was maintained with desflurane 4–8% end-tidal concentration. Unless contraindicated, a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), ketorolac 30 mg, and reversal, neostigmine 50 μg · kg−1 and glycopyrrolate 0.10 μg · kg−1, were given intravenously on case completion. Two minutes before extubation of the trachea, oxygen concentration was increased to 100% for patient safety.

During post-anesthetic recovery, all patients breathed supplemental oxygen 2 L · min−1 via nasal prongs for 30 min. Additional supplemental oxygen was administered if necessary to maintain SpO2 > 92%. Analgesia consisted of intravenous morphine 2–4 mg in PACU or oral acetaminophen with codeine 325 mg/30 mg in the post-recovery unit to provide subjects with satisfactory analgesia. Intravenous ondansetron 4–8 mg was administered as rescue medication for patients who vomited or experienced nausea for more than 15 min. Patients with persistent nausea or vomiting received intravenous diphenhydrinate and/or dexamethasone as second-line therapy.

Outcome assessments

Blinded observers assessed nausea and vomiting episodes at 30-min intervals from patient admission to the PACU until hospital discharge. Each subject rated her nausea on a four-point scale as: none, mild, moderate, or severe.3,4 Once discharged home, subjects recorded nausea severity and vomiting episodes in diaries for 24 hr postoperatively. Study nurses recorded these data by telephone interview at the completion of 24 hr. Morphometric and demographic characteristics of subjects in both treatment groups were recorded. Additional subject factors with potential to influence the primary outcome, such as previous PONV, smoking history, coexisting systemic diseases, concurrent medications, and alcohol use (more than one drink per day) were also documented. Anesthesia duration, total intravenous fluid, and all intraoperative and postoperative drugs (up to 24 hr postoperatively) were recorded.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome, defined prospectively, was the incidence of nausea and/or vomiting over the initial 24 postoperative hours. Any score of nausea or vomiting greater than “none” was regarded as “positive”. Secondary outcomes included in-hospital and post-discharge nausea and vomiting scores (evaluated separately), the incidence and total dose of postoperative antiemetics administered, time to oral intake, and time to discharge home. Univariate analyses were performed on dichotomous variables using the Chi square statistic, whereas the maximum severity scores for nausea and for vomiting were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test. Potential confounding factors were compared between the two study groups with unpaired two-tailed t tests or Chi square analyses. Group allocation and potential confounding variables having a univariate P value <0.15 were entered into a generalized mixed-effects regression model for stepwise regression. Factors contributing with a P value <0.05 were retained in the model. Results are presented as means ± standard deviation (SD), medians (interquartile ranges IQR), percentages, and odds ratios (95% confidence intervals). P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The required sample size was determined prospectively. The baseline incidence of PONV for this calculation was obtained from a previous unpublished study in 88 patients undergoing ambulatory laparoscopy at the IWK Health Centre. The study demonstrated a 30% incidence of PONV, as indicated by antiemetic usage, and a 60% subjective nausea rate, and these findings agreed with previously published rates.4 Therefore 138 patients in each group provided 85% power to detect a 50% reduction in any PONV (antiemetic use 30–15% [n = 138 per group] or subjective report 60–30% [n = 42 per group]) by the active treatment group with a two-sided α error of 0.05. To allow for 10% anticipated dropouts, the total study included 152 women in each group.

Results

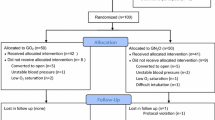

Three hundred four subjects were enrolled (Fig. 1) with a 71% recruitment rate. Twelve subjects were excluded from analysis because of protocol violations, including need to change volatile vapour ±100% oxygen concentration due to intraoperative tachycardia/bronchospasm ± arterial desaturation (n = 5); inadvertent usage of nitrous oxide (N2O) instead of medical air (N2/O2) (n = 2); unplanned admission for prolonged surgery/surgical complications (n = 1); and inadvertent ondansetron prophylaxis (n = 1). Eight subjects inadvertently received the incorrect group oxygen concentration based on the randomized group allocation, i.e., 30% oxygen instead of 80% oxygen or 80% oxygen instead of 30% oxygen. These results were retained and analyzed by original group allocation in the “intention to treat” analysis.

One subject had incomplete post-discharge data collection at 24 hr. These data were retained, however, as the primary outcome event was counted only once, irrespective of when and how frequently it occurred in the initial 24 hr. Also, this subject was positive for the primary outcome event prior to discharge; therefore, further data recording (i.e., complete 24-hr data) would not have impacted this result.

Subject demographics and morphometric characteristics were similar in both groups (Table 1). Intraoperative variables were similar in both groups (Table 2) with the exception of anesthesia duration, which was slightly longer in the intervention group than in the control group (2.7 ± 11.4 min, P = 0.02). There were no differences in the postoperative variables recorded in the PACU, including Aldrete score, SpO2, hemodynamic variables, opioid use, administered intravenous fluids, and time in the PACU (Table 3).

There were no differences in the post-discharge variables recorded at home (Table 4). Opioid, acetaminophen, NSAID, and antiemetic use were all similar between the two study groups. The highest incidence of PONV occurred in both groups during the first 6 hr after surgery and after discharge from the hospital. The incidence of any nausea and/or vomiting during the postoperative 24-hr observation period was 68.7% in the intervention group and 65.3% in the control group (P = 0.62). There were no differences in nausea alone, vomiting, or antiemetic use in either the PACU or up to 24 hr after discharge from hospital (Table 5). Sub-group analysis based on group allocation (not by intention to treat) also showed no significant difference between groups in the primary outcome (P = 0.59).

Group allocation and potential confounding variables having a univariate P value <0.15 were entered into a generalized mixed-effects regression model for stepwise regression. Factors contributing with a P value <0.05 were retained in the model (Table 6). The analysis showed patients with a prior history of PONV were six times more likely (CI95 1.83–16.95) to have PONV in this present study. Longer length of surgery (OR 1.04, CI95 1.0–1.08) and higher total pre-discharge opioid administration (OR 1.13, CI95 1.07–1.20) were also predictive of PONV. Both younger age (OR 0.93, CI95 0.88–0.98) and total morphine equivalents taken post-discharge (OR 0.87, CI95 0.82–0.96) were inversely related to the risk of PONV. Younger patients and patients who consumed fewer opioids in the initial 24 hr post-discharge at home experienced a 7% relative reduction (per year of age) and a 13% relative reduction (per morphine equivalent consumed) in the odds of PONV. Body Mass Index, smoking history, contraception use, and history of daily ethanol consumption were not associated with PONV risk.

Discussion

Nausea is defined as “a subjectively unpleasant sensation associated with awareness of the urge to vomit”.12 Vomiting is brought about by contraction of abdominal muscles, descent of the diaphragm, and opening of the gastric cardia to produce expulsion of gastric contents from the mouth.12 These events are controlled by the “emetic centre” located in the lateral reticular formation close to the tractus solitarius in the brain stem.13,14 The vomiting centre receives afferent stimuli from the pharynx, gastrointestinal tract, mediastinum, higher cortical centres (visual centre and the vestibular portion of the eighth cranial nerve), and the chemoreceptor trigger zone in the area postrema.13–20 The mechanism of postoperative nausea and vomiting includes vestibulo-cochlear stimulation, triggering of the central chemoreceptor trigger zone, and local gastrointestinal mechanisms.

Both Greif et al. 3 and Goll et al. 4 hypothesized that supplemental intraoperative oxygen may attenuate bowel ischemia from surgical stress and bowel manipulation during intra-abdominal procedures. Both are thought to release intravascular serotonin that may promote PONV by its action on the chemoreceptor trigger zone. Serotonin receptors are found in high concentrations in the area postrema of the brain stem.21–23 Unfortunately, the plasma half-life of serotonin is only a few minutes. As a result, the hypothesis proposed by Goll et al. 4 that intestinal ischemia releases intravascular serotonin to induce PONV has never been investigated directly with plasma serotonin measurements. Without such studies, one can neither confirm nor refute their proposal.

Previous studies evaluating supplemental intraoperative oxygen for the prevention of PONV have demonstrated conflicting results. In the first prospective randomized controlled trial investigating the antiemetic properties of supplemental intraoperative oxygen, Greif et al. allocated subjects to 80% intraoperative oxygen or 30% intraoperative oxygen and for 2 hr after surgery.3 They found that the incidence of PONV was reduced from 30% in subjects allocated to 30% oxygen to 17% in the group administered 80% oxygen.

The same group of authors subsequently showed that PONV was reduced from 44% (30% oxygen group) to 22% (80% oxygen group) when supplemental oxygen was limited to the intraoperative period in patients undergoing gynecological laparoscopic surgery.4 Later studies in subjects undergoing breast surgery, ambulatory gynecologic laparoscopy, thyroidectomy, laparoscopic cholecystectomy strabismus, or dental surgery failed to demonstrate any benefit from supplemental intraoperative oxygen on PONV.5–11 A recent meta-analysis of 1729 patients from ten studies has been published (since the conduct of this trial but prior to this current study publication) synthesizing the data from the aforementioned studies. Regardless of the type of surgery, the meta-analysis did not demonstrate any overall effect from supplemental intraoperative oxygen on PONV.24 Concerns regarding unbalanced patient characteristics and co-interventions have limited the validity of earlier randomized controlled trials that showed a benefit of supplemental oxygen on the reduction of PONV. These later studies may be limited by sub-therapeutic levels of supplemental oxygen.5

Our study adds further to this evidence and clearly demonstrates that supplemental intraoperative 80% oxygen, compared with routine intraoperative 30% oxygen, does not reduce the incidence of PONV during the initial 24-hr period among women undergoing laparoscopic gynecological surgery. No benefit was observed in any “subgroup” time periods, including immediately following surgery in the PACU (pre-discharge), time after discharge from hospital (post-discharge), early PONV (0–6 hr), or late PONV (>6–24 hr). Furthermore, supplemental oxygen did not improve PONV in women who had isolated nausea or vomiting.

Our study supports observations made by Purhonen et al. who investigated a similar group of subjects having ambulatory gynecological laparoscopy.6 With a smaller sample size (n = 100) and an intervention of 80% oxygen supplementation, which was continued postoperatively for 1 hr, they observed an overall incidence of nausea and vomiting of 62% in the 30% oxygen group and 55% in the supplemental 80% oxygen group during the first postoperative 24 hr (P = 0.49). Regardless of the mechanism of PONV, our study and that of Purhonen et al. 6 provide compelling evidence to refute the results of Goll et al. who first suggested that supplemental intraoperative oxygen prevents PONV in women undergoing gynecological laparoscopic surgery.4

Identification and development of decision trees or scores to predict risk of PONV have been elucidated by Apfel et al. 25 Risk factors identified to predict PONV include female gender, prior history of PONV, or prior history of motion sickness, non-smoking, and postoperative opioid use. Our regression analysis amongst those subjects who experienced the primary outcome revealed that younger age, prior history of PONV, longer length of surgery, and higher opioid administration in hospital were predictive of PONV and supports these previous works. Other factors that may be considered predictive, including history of ethanol consumption, BMI, and contraceptive use, did not predict risk of PONV in our current study. Interestingly, lower postoperative opioid consumption predicted risk of PONV and may signify that patients recognize that opioid pain medications may worsen nausea or that patients are not tolerating oral intake.

In conclusion, our randomized controlled trial did not demonstrate any clinical benefit of high inspired oxygen concentration (80%) on the incidence of PONV following short ambulatory gynecological laparoscopic surgery. Identification of individuals at high risk of PONV, such as younger women or those with a previous history of PONV, and finding strategies to reduce postoperative opioid dose become important when considering management of intraoperative and postoperative nausea and vomiting.

References

van Wijk MG, Smalhout B. A prospective analysis of the patient’s view of anaesthesia in a Netherlands’ teaching hospital. Anaesthesia 1990; 45: 679–82.

Gan TJ, Meyer TA, Apfel CC, et al. Society for Ambulatory Anesthesia guidelines for the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg 2007; 105: 1615–28.

Greif R, Laciny S, Rapf B, Hickle RS, Sessler DI. Supplemental oxygen reduces the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesthesiology 1999; 91: 1246–52.

Goll V, Akca O, Greif R, et al. Ondansetron is no more effective than supplemental intraoperative oxygen for prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg 2001; 92: 112–7.

Purhonen S, Niskanen M, Wustefeld M, Mustonen P, Hynynen M. Supplemental oxygen for prevention of nausea and vomiting after breast surgery. Br J Anaesth 2003; 91: 284–7.

Purhonen S, Turunen M, Ruohoaho UM, Niskanen M, Hynynen M. Supplemental oxygen does not reduce the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting after ambulatory gynecologic laparoscopy. Anesth Analg 2003; 96: 91–6.

Joris JL, Poth NJ, Djamadar AM, et al. Supplemental oxygen does not reduce postoperative nausea and vomiting after thyroidectomy. Br J Anaesth 2003; 91: 857–61.

Purhonen S, Niskanen M, Wustefeld M, Hirvonen E, Hynynen M. Supplemental 80% oxygen does not attenuate post-operative nausea and vomiting after breast surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2006; 50: 26–31.

Treschan TA, Zimmer C, Nass C, Stegen B, Esser J, Peters J. Inspired oxygen fraction of 0.8 does not attenuate postoperative nausea and vomiting after strabismus surgery. Anesthesiology 2005; 103: 6–10.

Piper SN, Rohm KD, Boldt J, et al. Inspired oxygen fraction of 0.8 compared with 0.4 does not further reduce postoperative nausea and vomiting in dolasetron-treated patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Anaesth 2006; 97: 647–53.

Donaldson AB. The effect of supplemental oxygen on postoperative nausea and vomiting in children undergoing dental work. Anaesth Intensive Care 2005; 33: 744–8.

Watcha MF, White PF. Postoperative nausea and vomiting. Its etiology, treatment, and prevention. Anesthesiology 1992; 77: 162–84.

Andrews PL, Davis CJ, Binham S, Davidson HI, Hawthorn J, Maskell L. The abdominal visceral innervation and the emetic reflex: pathways, pharmacology and plasticity. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 1990; 68: 325–45.

Borison HL. Area postrema: chemoreceptor circumventricular organ of the medulla oblongata. Prog Neurobiol 1989; 32: 351–90.

Borison HL, McCarthy LE. Neuropharmacology of chemotherapy-induced emesis. Drugs 1983; 25: 8–17.

Davis CJ, Harding RK, Leslie RA, Andrews PL. The organization of vomiting as a protective reflex. In: Davis CJ, Lake-Bakaar GV, Grahame-Smith DG, editors. Nausea and Vomiting: Mechanisms and Treatment. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1986. p. 65–75.

Costello DJ, Borison HL. Naloxone antagonizes narcotic self-blockade of emesis in the cat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1977; 203: 222–30.

Fetting JH, McCarthy LE, Borison HL, Colvin M. Vomiting induced by cyclophosphamide and phosphoramide mustard in cats. Cancer Treat Rep 1982; 66: 1625–9.

Borison HL, Harris TD, Schmidt AM. Central emetic action of pilocarpine in the cat. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1956; 15: 485–91.

Borison HL, Fairbanks VF. Mechanism of veratrum-induced emesis in the cat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1952; 105: 317–25.

Stafanini E, Clement-Cormier Y. Detection of dopamine receptors in the area postrema. Eur J Pharmacol 1981; 74: 257–60.

Atweh SF, Kuhar MJ. Autoradiographic localization of opiate receptors in rat brain. II. The brain stem. Brain Res 1977; 129: 1–12.

Waeber C, Dixon K, Hoyer D, Palacios JM. Localization by autoradiography of neuronal 5-HT3 receptors in the mouse CNS. Eur J Pharmacol 1988; 151: 351–2.

Orhan-Sungur M, Kranke P, Sessler D, Apfel CC. Does supplemental oxygen reduce postoperative nausea and vomiting? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Anesth Analg 2008; 106: 1733–8.

Apfel CC, Laara E, Koivuranta M, Greim CA, Roewer N. A simplified risk score for predicting postoperative nausea and vomiting: conclusions from cross-validations between two centers. Anesthesiology 1999; 91: 693–700.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by Dalhousie University Clinical Academic Enrichment Funding, IWK Health Centre Research Category B Funding, and IWK Health Centre Summer Research Studentship Funding. Dr. D.M. McKeen and coauthors would like to thank Faye Jacobson RN Research Coordinator, the IWK Department of Gynecology, and the PACU/OR nursing staffs for their help in the conduct of this trial.

Financial disclosure

The authors do not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McKeen, D.M., Arellano, R. & O’Connell, C. Supplemental oxygen does not prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting after gynecological laparoscopy. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 56, 651–657 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-009-9136-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-009-9136-4