Abstract

The purpose of this study was to elicit design guidelines for a teacher tool to support students’ diverse needs by facilitating differentiated instructions (DIs). The study used a framework based on activity theory and principles from universal design for learning. As for the research methods, design-based research methods were adopted, and as the first step, this study selected and interviewed four teachers and five community members. As a result, it identified facilitating and conflicting factors in practicing DI and analyzing the activity system in teaching for DI. From this analysis, specific user requirements were identified as blueprints for the design of new tools as mediating strategies. Furthermore, the findings helped establish five design guidelines for teacher tools to encourage DI practice. This study has implications for a teacher application as a mediating tool, which will facilitate DI practice by developing an understanding of teachers’ needs and the challenges they face in DI activities. It also presents a methodology for eliciting users’ requirements as the first step of design-based research to leads to innovations embodied in specific theoretical claims.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The theory of multiple intelligences has altered commonly held views on student intelligence and diversity in learning (Gardner 1983). To address issues of diversity, studies about differentiated instruction (DI) (Tomlinson 2001) and universal design for learning (UDL) (Rose et al. 2006) have also expanded views on learning styles by calling for greater inclusiveness. The concept of diversity in the classroom has also been extended to include those with different backgrounds and abilities (i.e., inclusiveness) (Ahn 2010; Ahn, Roh and Kim 2010). Addressing student diversity and considering student interests lead to enhanced student motivation and perseverance in accomplishing instructional goals (Subban 2006). Therefore, addressing DI in teaching can support student learning.

Recently, the Korean government has tried to promote adaptive learning through the SMART education initiative (MEST 2011) to address the increasing diversity of classrooms in Korea due to growth in the number of students from multicultural family backgrounds, the expansion of inclusive classrooms for the disabled, and the rise in the number of foreign students. However, even if teachers and educators recognize the need for DI, few teachers are able to accommodate this diversity in the classroom (Subban 2006), especially while they are teaching. Although societal and demographical changes in classroom demand teachers’ DI, however, teachers lack training to fully support all students’ learning by practicing DI.

Thus, a tool to support teachers to teach with DI framework would help the teachers teaching and students learn in the classrooms. Teachers need DI guidance to meet the students’ needs and promote their learning. The DI includes instructional strategies, guidelines, systems, models, frameworks, and toolkits. When teachers’ DI activities are supported and mediated by tools and guidance, this has a significant impact on their desire for DI practice (mental awareness), their habit of DI practice (the nature of their teaching activities) (Nardi 2001), and most importantly for student learning (Gardner 1983; Rose and Meyer 2002).

To develop a practical teacher support tools, it is first necessary to understand the difficulties and identify teachers’ needs. Activity theory (AT) provides a theoretical framework for understanding the context of human beings and their activities (Nardi 2001). AT is widely utilized as an analytical framework to determine specific requirements for a particular tool being developed and to analyze problems with existing tools (Preece et al. 2007). The findings from this analysis might provide valuable information in the design of new tools as mediating strategies (Choi and Kang 2010; Jonassen and Rohrer-Murphy 1999).

Therefore, the aim of this study was to suggest design guidelines for teacher tools to facilitate DI practice by understanding teachers’ needs and challenges in DI activities, using a AT framework as a theoretical background.

Theoretical background

Activity theory

A review of the cultural–historical research traditions underlying AT offers insight into the artifact (tool) as a mediated act in an environment where users are interacting (Nardi 2001). Engeström (1999) graphically expanded Vygotsky’s triangular model, integrated Leont’ev’s work on collective activity, and defined the “Activity System” (AS) as an expanded triangle model that includes the community, the division of labor, and the rules, as depicted in Fig. 1. Figure 1 shows the paradigm shift of focus from individual activity to the interrelation between the individual and the subject’s community, which has led diverse disciplines to apply AT in order to examine human practices (Kuutti 1996; Barab and Squire 2004).

Activity system (Engeström 2001 p. 134–135)

The role of tools (instruments) in AT has been developed throughout three generations. A tool functions as a form of mediation in an interaction between a human being and an environment for the behavioral transformation of the individual. However, this has been expanded to be conceptualized as a form of mediation that is collectively involved with the community in the second generation (Engeström 1999). Tools can be either physical or abstract (Preece et al. 2007). Preece et al. (2007) emphasized the relationship between human development and mediated artifacts as a change from acting on the world to that which is mediated by something else. Thus, new activities from new artifacts lead to new learning and influence culture, society, and history. These days, smartphones (a new tool), influence all facets of people’s lives (Betz 2012). Therefore, in the present study, smart tools (e.g., smartphone or smart pad) are examined as instruments which mediate and promote DI practice.

Meaning of the tools and contradictions in activity theory

Indeed, a variety of studies have used AT as an analytical lens to understand the impact of newly introduced artifacts or the systematic tensions in the learning environment as influenced by technology (Yamagata-Lynch 2003, 2007; Choi and Kang 2010). AT in practical design can be utilized to obtain specific user requirements based on the analysis of tensions between the components of the activity system.

AT in practical design

Preece et al. (2007) argued that identifying and analyzing the components of the AS depends on the researchers’ interpretations. In addition, AT analysis requires a large number of interviews to collect and articulate data. Yamagata-Lynch (2007) argued that AS analysis has great potential to manage the complicated “qualitative design-based research (DBR) data set” (p. 453). He used the AS as a descriptive tool to understand the interaction between teachers and their professional development program as integrated by technology. DBR is an emerging empirical educational research methodology suggested in order to improve the experimental design research (The Design-Based Research Collective 2003). DBR collective argue that it leads to innovations embodied in specific theoretical claims about teaching and learning and promote understanding “relationships among educational theory and designed artifact, and practices (p5).” The characteristics of this DBR approach are naturalistic, process oriented, iterative, and involve creating a tangible design (Barab and Squire 2004). Jonassen and Rohrer-Murphy (1999) also suggested a framework to determine the components of the AT system and proposed some questions that can be utilized to analyze an AS for designing a new learning environment. For the purpose of creating a new tool for DI, interviews were utilized as recommended by Preece et al. (2007) based on the framework suggested by Jonassen and Rohrer-Murphy (1999).

Differentiated instruction

George (2005) emphasized that DI should be an essential part of the classroom experience for students, building on his research and experience of 40 years in the field of education. However, differentiation does not mean that all students must reach the same level. Instead, every student should have the opportunity to perform at their best (Tomlinson 2003). Many researchers (Winter 1985; Park and Lee 2003) have proposed providing instructional environments responding to the different needs of learners. The direction of these studies is varied, and the terms are also diverse, ranging from a focus on differentiated learning to adaptive instruction. Although the focus was slightly different, this foundational goal attempts to accommodate learner needs using various approaches (Winter 1985). Therefore, instructional methods for the foundational goal of supporting student needs are labeled as DI in this study.

Differentiated instruction models

Park and Lee (2003) divided DI into three different approaches based upon aspects of instructional methods for adapting to different learners. Hereafter, the terms “DI” and “adaptive instruction” are used interchangeably, as explained above. The DI strategies that Tomlinson (1999, 2000 and 2001) suggested for mixed-ability classrooms are a type of macro-adaptive instructional (MAI) model among three approaches. However, studies investigating MAI models have not made much progress due to difficulties in developing curriculum design, teacher training, resource limitations, and organizational resistance (Subban 2006). Park and Lee (2003) also mentioned another reason for the limited success of these models despite numerous trials and diverse efforts. This is due to their development based on unverified theoretical assumptions and the difficulty that DI is proactively done prior to teaching, so it is not easy to reflect a learner’s change in a progressive way. In recent years, these problems have been tackled by computer technology, with new innovative attempts and to provide better learning environments for all students grounded in a practical framework.

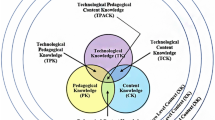

Universal design for learning (UDL) as a macro-adaptive instructional framework

By integrating technology into the classroom, UDL has been proposed as a practical framework to reduce barriers to instruction, to provide appropriate accommodation, support, and challenge, and to maintain high achievement expectations for all students (Rose and Meyer 2002). The flexibility and additional support through technology might make it possible for students with some learning problems as well as for students with special needs to have more accessible opportunities toward learning. It is also beneficial to design the curriculum for all students’ needs, so that accessible methods, materials, and assessment are suggested for all (Hall et al. 2003). The learning support through the UDL framework can help to implement DI where teachers can customize the criteria for teaching strategies, materials and means of student expression, monitoring student progress through ongoing evaluation (Rose and Meyer 2002). The flexibility and UDL framework have been built based on scientific research into “the learning brain.” If educators categorize learners into smart, not smart, disabled, or not disabled, it is grossly oversimplified because students are different within and across all three brain networks: cognitive, strategic, and affective networks, showing a unique assortment of strengths, weaknesses, and preferences for learning (Hall et al. 2003). In the classroom, students’ strengths or weaknesses based on patterns of strong and weak points across all three networks should be considered when teachers provide an individual student with learning support. Based on the assumption of dealing with each brain network in a learning context, CAST (2011) developed UDL guidelines as “an articulation of the UDL framework” (p. 4) to help anyone who plans curricula (goals, methods, materials, and assessments) to minimize the learning barriers and support all learners. The National Center on Accessing the General Curriculum also demonstrates that “DI is well received as a classroom practice that may be well suited to the three principles of UDL” (Hall et al. 2003, p. 9). In addition to teaching methods, CAST provides a variety of toolkits such as UDL studio, planning for all learners (PAL) toolkits, and e-book builders. These toolkits also help teachers to practice DI and provide learning scientists with practical guidelines for DI practice. This learning support with a UDL framework can help to implement DI where teachers can customize the criteria for teaching strategies, materials and means of student expression, and monitor student progress through ongoing evaluation (Rose and Meyer 2002).

Teachers’ tools for DI

Since the role of teachers is crucial in DI (Smith and Throne 2007), tools for teachers that mediate difficulties associated with DI might help to promote DI practice (Nardi 2001). Gibson and Hasbrouck (2009) argue that teachers need tools and proven methods to practice DI. Moreover, there have been some studies on DI tools for teachers including the system, guidelines, and model (Gordon 2007; Gibson and Hasbrouck 2010; Gregory and Chapman 2007). Based on a review of these tools, the most common aspects and implications of tools that effectively support teachers are summarized below (Cha 2013).

First, analyzing student characteristics and needs should be done at an early stage. Second, teachers need to plan a prescriptive instructional design based on the evaluation of learners, including their goals, resources, and strategies. Third, managing student data are an essential part of the teacher’s role, and therefore, some studies have suggested a management system. There is so much data to be managed by teachers in order to practice DI, including students’ characteristics, needs, lesson goals, strategies, and assessments. Consequently, a well-designed management system is required. Fourth, ongoing revision in terms of student interests as well as assessment of achievements should be conducted in order to provide constant feedback. Fifth, it is very helpful for teachers to share good instructional methods and examples. Teachers feel more comfortable when they have colleagues as mentors (Lee et al. 1999). Thus, peer coaching and the sharing of effective models can encourage teachers to improve their DI practice. These five implications provide guidance for the design of a new tool to support teachers and to facilitate their DI practice.

Characteristics of the smart tools

The boom in smart technologies is transforming the paradigm of education toward providing intelligent and customized teaching and learning environments (KISA 2012; Kim 2011; MEST 2011; KERIS 2011). In education, those studies have also tried to discuss the effects of new smart devices on teaching and learning. From such effort, this study will also consider how smart technologies could be applied to design an innovative tool to support teachers and facilitate their DI practices.

In fact, smart technology is not a specific technology. Instead, it refers to a technology that is sensitive to what is happening everywhere and responds quickly to provide personalized products and services through analysis and forecasts (Kim 2011). Both from the definition of smart technologies and through the review of relevant articles to the keywords such as “smart” and “technology” (KISA 2012; Kim 2011), the smart devices might be taken with some technologies such as cloud computing, Web 2.0, analytics (semantic Web and Web 3.0), and so on into account.

Cloud computing refers to the systems that use hardware and resources in the “cloud” as a specialized data center hosted by thousands of servers. It makes it easier for individual users to use an application on a wide range of computer platforms (Johnson, Levine, Smith and Smythe 2009). In other words, the value of cloud computing as a way to provide access to services and tools without the need to invest in additional infrastructure makes teaching and learning data management an attractive option for many educators (Johnson et al. 2010). The cloud systems that synchronize data between computers to provide access from anywhere help smart devices connected to each other easily and users to work effectively with the variety of smart devices according to the context (Simonite 2012).

Web 2.0 can be defined as a technological feature that facilitates participatory knowledge sharing and collaboration on the Web (KERIS 2011). It was enhanced by social network services to help build social networks and relations by online media to share interests and activities. Moreover, the development of smart media has accelerated knowledge sharing for educators by connecting to and offering the information anywhere and anytime around the globe.

Web 3.0 is a set of technologies that provides efficient ways to make computing systems organize and draw conclusions from online data. It becomes possible due to the power of advances in data mining, interpretation, and modeling including the semantic Web that seeks to give computers the ability of intelligence by understanding the content on the Web (Boland 2007). It is expected that the next wave of technologies might ultimately blend “semantic Web tools with Web 2.0’s capacity by dynamic user-generated connections (p. 2).” This means that the computing system can become more intelligent with the knowledge that users are creating and sharing. Allowing users to connect, create, share, and to modify their own systems offers customized and individualized data with their own structure on the way users think in a smarter way (Boland 2007).

One of the example which was applied the smart technology into DI contexts is the smartphone version of the PAL tool (Cha and Ahn 2011). This tool tried to demonstrate how the advantages of new smart technologies might help to overcome some macro-adaptive model’s weaknesses and provide an efficient and usable way of practicing DI.

Methodology

Research design and procedure

Interviews were conducted to elicit users’ difficulties and tensions in DI practice, as recommended by Preece et al. (2007), both to identify users’ needs and to establish system requirements for the design of a new tool for DI practice. By analyzing the interview data, an AS for DI practice, conflicting factors (CFs), and facilitating factors (FFs) were established. From these factors, guidelines were created to design a teaching tool for DI (Fig. 2).

Choice of setting

In the present study, a primary-school setting was chosen to examine contradictions in DI practice by primary school teachers in the context of the Korean education system. In the present study, the main subjects were teachers actively involved with students in the classroom (Table 1).

Participant selection

Purposeful sampling to select information-rich cases (Patton 1990) was conducted for the interviews. Four teachers with different positions at the primary school were recruited based on criteria determined from the DI context. The only prerequisite was that they met at least one of the following four characteristics. They are the selection criteria for the purposeful sampling.

In addition, since we were looking into common DI tools, we purposefully sampled a group of parents, administrators, and special education teachers. Parents play a crucial role in children’s learning, while administrators’ attitudes and support are key factors in making DI implementation possible (Willis and Mann 2000). In order to understand the differing relationships and roles of subject and special education teachers in dealing with students with special needs, a special education teacher was included as shown in Table 2.

Instruments

The data collection approach was a semi-structured interview. Four different pre-structured scripts were designed for different groups, but the basic frameworks among the four scripts were similar. The framework and questions were designed based on the factors and framework proposed by Jonassen and Rohrer-Murphy (1999) to determine the components and their interrelationships for DI practice and context. In addition, artifacts used by the teachers, knowledge shared through the education portal site including teaching materials and tips, and their performance evaluations were analyzed to identify the details of their activities and their precise needs (Rizzo et al. 2005).

Analysis of the data

AT was utilized as an analytical lens for identifying, coding, and categorizing qualitative data. First of all, the data were transcribed and coded based on the components in the activity systems. As a result of the analysis, conflicting and FFs (Choi and Kang 2009) in DI practice were identified. Table 3 describes the coding scheme and definitions according to category.

Results

Activity system of DI practice

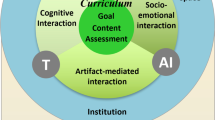

One of the findings from analysis of the interviews was the activity system about DI practice at Korean primary school environments. In this study, subjects are the class teachers shown in Fig. 3. Data from interviews demonstrated that most of the Korean classroom teachers barely differentiated their instruction, due to numerous conflicts which will be discussed in more detail below. However, they did unconsciously and unintentionally try to provide DI to their students, even if the range and amount was very small.

In fact, while teachers were discussing about the DI in the interview, they said that they realized the importance of DI, and they admitted that understanding differences among students could be a basic consideration for their students, and could make it possible for them to have a different starting point depending on the students’ levels and characteristics.

Another outcome could be establishing a good learning environment in the classroom. For example, the behavior of students with special needs or other challenges has an influence on the overall learning environment of the classroom and might interfere with other students’ learning. However, teachers argued that providing different materials and instructions to students with special needs or problems based on their own interests might encourage them to more actively participate in lessons.

It also reveals that teachers perceived students’ enthusiasm about their teaching from the strategies. Therefore, their behaviors were changed, and this in turn improved the atmosphere in the classroom. “(…) the number of absences was significantly reduced and their attitude in a class became positive. It can cause a very good atmosphere in a classroom” (Kim).

It was identified that the community members in the activity system about DI practice would be subject teachers, special teachers, parents, and administrator. To illustrate, some classes such as English, music, and physical exercise at the Korean primary school are taught by other subject teachers, while most of subjects except for such subjects are taught by their own class teacher. As one of the divisions of labors between class and subject teachers, class teachers consider students in their classes like their own children, so they are interested in any problems that happened during subject lessons in their classroom. Thus, it was a tacit rule that class teachers would ask subject teachers for information about how the subject lessons were going in their classes, and whether or not students were having trouble. They frequently had informal conversations either by messenger, during lunch, or during chance meetings in the hallway. “(..). asked the subject teachers about how it was going with today’s class? Student’s attitude is different to the class and the subject teacher. They didn’t usually listen to subject teacher’s instructions well compared to me” (Kim). There were many divisions of labor and rules between community members as shown in Fig. 3.

As an example for the rule, the class teacher asked aids to the special teachers about the guidance and teaching materials for their special students. Special teachers also talked with class teachers about the attitude and learning status of the student with the special needs in the inclusive class, expecting that the class teacher consider allocation of a proper seat location, pairs, learning materials and so on. However, nowadays, due to the convenient communication media such as messengers and SMS, teachers try to keep in regular touch with parents at the class, so it is revealed that the communication between parents and teachers are getting promoted more through media (Goodall and Vorhaus 2010).

Facilitating factors

The interviews with teachers and community members helped to identify 14 FF in five categories for DI practice in Korean primary schools (Table 4).

Most of the community members felt that the most important part of the practice of DI was to identify students’ characteristics and needs. In addition, in order to maintain the student’s information, teachers thought that it might be beneficial to have student’s management tools. In fact, as one of the tools, teachers are utilizing the annual schedule to record information and reflect student’s needs. “to identify student’s characteristics is the most important thing in DI practice” (All teachers mentioned this factor).

Furthermore, to practice DI, teachers need various effective teaching materials with specific guidelines and frameworks for DI strategies as most of them expressed difficulties with DI practice. From their perspective, professional development for DI should be offered to the community as well as to teachers. “If I have accurate teaching strategies such as A for A type student, B for B type student, and C for C type student, I might utilize it” (Kim). Knowledge sharing is one of the important techniques to facilitate DI practice. “When I don’t know what to do for the student with the special needs, I go on the internet and ask other teachers about their experience”(Cha). “I usually get good teaching materials and tips from the I-scream” (Lee). In terms of tools to support DI, teachers utilize notes and word processors to record student characteristics. In interactions between community members, teachers utilize various communication tools such as phone, messenger, and SMS. There has been a trend toward expanding opportunities to interact with community members. “I take a note about my students. The notes help me to write and send student’s records about their learning progress and their school life to parents” (Lee, Kim). “I ever gave and took a special note for a student with ADHD to his mother” (Cha). Additionally, class teachers try to match other students with those with special needs, and student diversity and needs are met by allocating the appropriate seating and groups for collaborative work. “When I consider allocating seats or groups, I try to match the individual student’s grade, personality, and their special needs” (Lee).

Conflicting factors

Interviews with teachers and community members revealed CF that caused difficulties in DI practice. The analysis identified five categories of 33 CFs. One of the most critical issues for DI practice was difficulty with the management of student information. As mentioned in the analysis of the FFs, the first task of DI is to identify individual students’ traits. However, it is not easy for a class teacher to manage all of the data about individual differences due to the number of students in a class. Parents may feel that they have less access to their children’s school information, and teachers also provide parents with few chances to contribute to identifying their children’s needs. “I don’t know our children’s school life” (Choi). “The best method to understand students is to talk with parents” (Choi, Cha). The exchange of information between teachers and parents is pivotal in accurately identifying students’ needs. Even when sufficient information on students is exchanged between teachers and parents, their perspectives on students’ characteristics may differ. In addition, when knowledge sharing between teachers with an ICT tool was suggested in interviews in order to reduce problems, teachers expressed concerns about sharing written information about students with regard to their attitudes and affective aspects outside of official profiles and records. “I’m worried about the written records in terms of private information security” (Lee). “If my child’s information is sent to other teachers such as next class teacher, the agreement from their parents should be gotten” (Dang).

Teachers and community members also argued that it was not possible to practice DI due to education policies and systems that emphasize student grades and the national assessment of educational achievement rather than individual students’ affective aspects. When discussing the introduction of a new tool to support the practice of DI, teachers expressed some concerns about ICT tools. From the interview, Lee discussed that experienced and novice teachers did not want to utilize an ICT tool because they were not accustomed to it, so they were concerned that it would increase their workload. The teacher gave as an example the National Education Information System (NEIS), a new tool that caused a lot of problems and imposed increased workload (Table 5).

Another common complaint dealt with the installation and registration of new applications with the same functions. For examples, MSN and KaKaOTalk are both messenger services used by teachers, but whenever a new tool was introduced, they had to install a new messenger program and register people all over again. “Old and novice teachers don’t want to use the ICT in education” (Lee). “Whenever a new program was introduced, I have to install it again in spite of the same functions(…)” (Kim).

One of the biggest conflicts in DI practice in Korean primary schools stems from interactions between community members. For instance, parents felt burdened by interacting with their children’s class teachers because they were afraid of making mistakes during the conversation and that this might have a negative impact on their children. Teachers also felt burdened by talking with parents and having to offer student information on a regular basis due to lack of time. Due to these reasons, opportunities for interactions between teachers and parents have decreased. Similarly, a subject teacher also experienced that class teachers expressed a negative reaction when they provided student’s negative attitudes in a class in charge. From these reasons, opportunities for interaction between teachers and parents have decreased.

“Subject teachers sometime talked to me that A has a big problem in a class, but he has never had any problem with me” (Kim). “Teachers usually write a good comment about the student on report cards” (Lee).

There were also many issues raised by teachers and community members regarding government enforcement of inclusive classes for students with special needs. These issues have led to disturbances in teaching and learning in the classroom. In fact, although individualized education plans are written and shared by special needs teachers, the special needs teachers reported that they are not practical in inclusive classrooms. Overall, the government enforcement of inclusive classes at Korean primary schools is not practical, so special needs teachers usually take care of students with special needs separately in special classes. “Teachers usually don’t know about how to use the assistive technology. (…) Depending on the class teacher’s attitude toward students with special needs, their behaviors are very different (….) (Yang)”.

Implications

The current study described the context of DI practice in Korean primary school environments through the analytical lens of activity system. These contextual data helped to identify and analyze the contradictions and FFs of DI practice by eliciting users’ requirements for the design of new tools as mediating strategies for DI based on qualitative DBR (Yamagata-Lynch 2003, 2007). As reviewed in the characteristics of DBR (The Design-Based Research Collective 2003; Barab and Squire 2004), this paper as the first step of the DBR process revealed the relationships between theories related to DI and DI practices in a real context. In addition, it also provides background data to implement the artifact which will be designed to promote DI practice from an innovative perspective.

Based on the analysis of user requirements, design features and functions for teacher applications of smart tools to facilitate DI practice were suggested.

Facilitating and conflicting factors for DI practice

FFs and CFs were categorized into five domains: student information management, education policy and system, tools and resources, communication (interaction), and students with special needs. Through the analysis, the linkage between conflicting and FFs was revealed and the categorization verified. This analysis demonstrated that if the CFs could be dealt with, DI practice might be more encouraging for teachers because the consequent solutions could play a facilitating role in DI practice. For instance, a problem in student information management was the difficulty teachers had in identifying individual differences in students due to the large number of students in the classroom. If there were opportunities to record student characteristics as soon as they are observed or to exchange student information between community members, identifying students’ needs would be more straightforward. Thus, effective student information management might also lessen inconsistent viewpoints between subject and class teachers about individual student characteristics by addressing CFs in the student information category. As shown in this example, CFs and FFs are closely intertwined and they present key clues to defining initial design guidelines for teacher tools to promote DI practice, coinciding some of the design guidelines elicited from currently utilized tools (Cha 2013).

Design guidelines for a teachers’ tool to promote DI

Provide mediating tools (options) to facilitate student information management to identify student characteristics and needs at an early stage

An analysis of students’ characteristics and needs should be conducted at an early stage to differentiate classroom instructions as indicated by previous studies. Student information management plays an essential part in DI practice, as it is both a conflicting and FF in the analysis of AS about DI practice. Thus, teachers need an application or tool which will facilitate student information management. Having a tool that would allow teachers to record student information and update it frequently when they identify the individual needs of their students might be a more effective way to prepare lesson plans customized to individual students. Such a tool could help school community members share student information and establish a common understanding of students’ strengths and weaknesses. If the tool is implemented by smart technology, community members including teachers can easily obtain the information anytime and anywhere through any media (KERIS 2011; Johnson, Levine, Smith and Smythe 2009). Furthermore, the student’s data can be automatically updated and revised through ongoing practices (Cha and Ahn 2011).

By applying the student’s data from such tools into UDL principles, student information can be organized according to three different networks: cognitive, strategic, and affective (Rose and Meyer 2002). The class profile maker from PAL (planning for all learners) UDL toolkits CAST provides a practical process to summarize the student’s strengths and weakness according to UDL principles. This analysis of student’s characteristics can be a basis to find most proper teaching strategies to differentiate instructions in their class (CAST n.d.).

Provide mediating tools (options) to find different teaching strategies and resources to support diverse needs

Most importantly, teachers have to plan prescriptive teaching strategies and resources customized to students’ information (Gordon 2007; Gregory and Chapman 2007). As described in the CFs, one of the reasons why DI cannot be put into practice is lack of knowledge and teaching materials. Teacher tools should be designed to play a mediating role between teachers and their practice, using teaching strategies and resources in a more convenient and effective way to promote DI activities. More effective use of student information provides more opportunities for teachers to plan customized instruction for individual students. For instance, in a commonly utilized teaching strategy, seat arrangement and group allocation can be supported through a tool in a more efficient and straightforward way in order for teachers to voluntarily adopt classroom activities. UDL principles also provide guidelines to practice DI in real contexts (CAST 2011). In addition to UDL principles, CAST provides various examples of lessons, activities, strategies, and templates to share teaching strategies and resources for DI practice (CAST n.d.).

If the tool is implemented by smart technology, it might provide the most proper teaching strategies and resources intelligently based on student’s information through Web 3.0 and sematic Web (Borland 2007). From a knowledge sharing perspective, through Web 2.0, strategies that other teachers customized to similar cases could be shared (KERIS 2011).

Provide communication options to foster interaction and sharing of student information among community members

Many communication difficulties among school community members were observed. However, if these issues were addressed and communications between them more effectively supported, it could contribute to more active DI practice in the classroom as shown from the qualitative analysis. Interactions between class and subject teachers and between class and special needs teachers are essential methods for teachers to more accurately identify their students’ characteristics and to reflect their students’ needs into instructional strategies. Moreover, there were some interaction problems between class and subject teachers. Thus, the tool should be designed to play a mediating role in fostering interactions among them. Current smartphone technologies such as messenger, SMS, and alarms can support communication in more active and accurate ways (Goodall and Vorhaus 2010). Such a system could intelligently connect teachers to community members in terms of student information. In particular, the analysis data suggested that parents rarely have an opportunity to receive their children’s information and feel burdened by having to have direct conversations with teachers. Teachers also reported difficulties in offering negative information about their students to parents. To cope with these issues, a tool could be designed to foster indirect interactions among community members on the basis of evidence-based information. However, the most crucial aspect in the feature of indirect interactions is to identify the range of the information disclosed among members.

As discussed in the interview, some parents are reluctant to share their child’s negative information in an official format. Parents agreed that positive student’s data might be good to share, but they though that negative comments might influence on the first impression and perception of students. Therefore, the scope to be allowed to disclose should be positive aspects first, but the levels and fields in student’s data, especially negative ones permitted to a specific member should be determined through iterative evaluations in a future further DBR study.

Provide options to share knowledge in order to encourage active participation and encourage collaboration among teachers

It is very beneficial for teachers to share good instructional materials and experiences. Teachers tend to put considerable faith in their colleagues as mentors (Rose et al. 2006). Knowledge sharing is a FF for DI practice, and teachers have adopted teaching materials and tips from community sites. Although teachers reported the benefits of knowledge sharing and experience with colleagues, there are not many teachers who voluntarily participate in sharing. Therefore, tools that enhance the participation in knowledge sharing and collaboration in knowledge construction can serve as a benchmarking system for teachers to improve DI skills and gain differentiated resources for individual students. Furthermore, research into how to promote voluntary knowledge sharing between teachers should be undertaken.

CAST has also made efforts to build a place to share teacher’s knowledge about UDL and DI practice, and through this place, teachers can be promoted to participate in collaboration to realize the DI practice (CAST 2011). These are strategies, activities, lessons, templates, e-books, and resources which teachers can utilize multiple means of representation, action and expression, and engagements in their class.

Provide options for performance evaluations and various evaluation methods to assess and reflect student progress

Ongoing revision, both in terms of student interests and needs as well as assessment of achievement, should be conducted in order to examine student progress and to provide constant feedback (Cha and Ahn 2011). However, it is more important to assess student performance, including knowledge and skills, in authentic tasks in real contexts rather than traditional paper-based tests (Wren 2009). In fact, UDL theory also suggests that it is more successful when DI is put into practice with different evaluation methodologies customized to students’ characteristics (Rose and Meyer 2002). Moreover, if teachers might provide different options for an individual student to choose in the evaluation form, it might motivate students to reveal their academic performance and progress based on their affective network (Rose and Meyer 2002). From this perspective, it is vital for teachers to have a variety of analytical rubrics for performance evaluation and to have a template to record student performance. Thus, a performance evaluation tool should be designed in such a way that student strengths and weaknesses can be accurately recorded and reflected in teaching strategies for DI and that more options in assessments are suggested.

Limitations and further research

Not all of the identified CFs can be addressed by the design of an innovative tool. Problems and conflicts in educational policy and systems require the transformation of the entire educational culture and environment. In this respect, the analysis of problems and conflicts in current DI practice in a Korean primary school context can be utilized not only for the analysis of users’ needs and for designing a new tool, but also to review which aspects of the educational system and environment should be altered to benefit students and DI practice. Thus, this study may present different avenues for research that can address further challenges.

The methodology of using AT as an analytical lens has been criticized, as leading to oversimplified and generalized outcomes in complicated research areas (Choi and Kang 2010). This study also presented generalized design guidelines for teachers’ tools to promote DI practice. Thus, it will be necessary to further measure and evaluate the feasibility and effectiveness of these design guidelines in real-life implementations and contexts through a further DBR study. The limitation on the number of participants should be also addressed by iteratively evaluating tools in real contexts which will be designed to apply such design guidelines as the further step of the DBR study (Barab and Squire 2004).

Conclusion

This study established initial design guidelines for a new teacher tool that will facilitate DI practice by applying AT. To achieve this objective, interviews with teachers and community members were conducted and the interview data were analyzed in terms of three aspects: activity system for DI practice, FFs, and CFs in the practice of DI. The results showed that activity system helped to understand DI practice in the Korean primary school environment. The FFs provided insight into how best to promote DI practice among teachers. Barriers faced by Korean primary teachers in DI practice were also revealed. Based on the analysis, design guidelines for a smart-tool teacher application were suggested, presenting a systematic solution where CFs could be addressed and FFs could be promoted.

An analysis of users’ needs has a number of practical implications for DI that could not be gained from theory alone. The activity system analysis pinpointed obstacles faced by teachers in the DI practice in current teaching environments. These obstacles were related to workloads, educational systems and policies, and the inefficiency of tasks both directly and indirectly related to DI. Therefore, comprehensive efforts surrounding the transformation of educational environments should be made in order to facilitate DI. Toward this goal, the present study suggests design guidelines for the development of innovative teacher tools that will support DI for classroom teachers. In addition, the culture of practicing DI in the classroom can provide students with a less distracting classroom atmosphere. Such small changes can make students’ attitudes more positive and promote a better learning environment.

References

Ahn, M. L. (2010). Implimentation of UDL and TPACK for inclusive education: Multicultural education for preservice teachers. International Conference for Korean Society for Multicultural Education, Seoul, Korea.

Ahn, M. L., Roh, S. J., & Kim, S. N. (2010). Translated the universally designed classroom: Accessible curriculum and digital technologies. Seoul: Hanyang University Press.

Barab, S., & Squire, K. (2004). Design-based research: Putting a stake in the ground. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 13(1), 1–14.

Betz, B. (2012). One Billion Smartphone Users by 2016, Forrester Says, InvestorPlace, Retrieved 16 Feb 2010 from http://www.investorplace.com/2012/02/onebillion-smartphone-users-by-2016-forrester-says-aapl-msftgoog/.

Boland, J. (2007). A smarter Web, technology review. MIT. Retrieved from http://www.technologyreview.com/read_article.aspx?id=18306&ch=computing&a=f.

CAST (n.d.). UDL Toolkits: Planning for All Learners (PAL). Retrieved from http://www.cast.org/teachingeverystudent/toolkits/tk_introduction.cfm?tk_id=21.

CAST (2011). Universal design for learning guidelines version 2.0. Wakefield, MA: Author.

Cha, H. J., & Ahn, M. L. (2011). New design of a smart-phone version of PAL tool. The Journal of Educational Information & Media. 17(1), 215–232.

Cha, H. J. (2013). Design implications for teachers’ tools in differentiated instruction through case studies. Educational Technology International. 14(1), 55–74.

Choi, H. S., & Kang, M. H. (2009). Applying an activity system to online collaborative group work analysis. British Journal of Educational Technology. 41(5), 776–795.

Choi, H. S., & Kang, M. H. (2010). Applying an activity system to online collaborative group work analysis. British Journal of Educational Technology., 41(5), 776–795.

Engeström, Y. (1999). Learning by expanding: An activity – theoretical approach to developmental research (German/Japanese ed.). Retrieved from http://lchc.ucsd.edu/mca/Paper/Engestrom/expanding/toc.htm.

Engeström, Y. (2001). Expansive learning at work: Toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization. Journal of Education & Work, 14(1), 133–156.

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences, Twentieth-anniversary edition with a new introduction by the author, Basic Books, A Member of the Perseus Books Group.

George, P. (2005). A Rationale for differentiating instruction in the regular classroom. Theory into Practice, 44(3), 185–193.

Gibson, V., & Hasbrouck, J. (2008). Differentiated instruction: Grouping for success. New York: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

Gibson, V., & Hasbrouck, J. (2009). Differentiating instruction: Guidelines for implementation: training manual. Wellesley Hills, MA: Gibson Hasbrouck & Associates.

Goodall, J., & Vorhaus, J. (2010). Review of best practice in parental engagement, Department for Education, Research report DFE-RR156. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/182508/DFE-RR156.pdf.

Gordon, A. M. F. (2007). Preparing teachers to use an instructional management system to differentiate instruction (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). USA: Newark University.

Gregory, G. H., & Chapman, C. (2007). Differentiated instructional strategies: One size doesn’t fit all (2nd ed.). California: Corwin Press Inc.

Hall, T., Strangman, N., & Meyer, A. (2003). Differentiated instruction and implications for UDL implementation: Effective classroom practices. NCAC. (NCAC Agreement No. H324H990004). Retrieved from http://aim.cast.org/learn/historyarchive/backgroundpapers/differentiated_instruction_udl/.

Johnson, L., Levine, A., Smith, R., & Smythe, T. (2009). The 2009 Horizon Report: K-12 Edition. Austin, Texas: The New Media Consortium.

Johnson, L., Smith, R., Levine, A., & Haywood, K. (2010). The 2010 Horizon Report: K-12 Edition. Austin, Texas: The New Media Consortium. Retrieved from http://wp.nmc.org/horizon-k12-2010/.

Jonassen, D. H., & Rohrer-Murphy, L. (1999). Activity theory as a framework for designing constructivist learning environment. Educational Technology Research and Development, 47(1), 61–79.

KERIS (2011). Future schools, Report for the workshop of the policy-making (KERIS Publication No. RM 2011-8).

Kim, D. H. (2011). The smart technology to make smart future. Keynote speech, Entru World 2011, Retrieved from http://www.acrofan.com/ko-kr/commerce/content/20110426/0001060201.

KISA (2012). KISA’s Top 10 Internet Issues of 2012. Retrieved from http://www.advancedtechnologykorea.com/?p=10424.

Kuutti, K. (1996). Activity theory as a potential framework for human-computer interaction research. In B. A. Nardi (Ed.), Context and consciousness: Activity theory and human-computer interaction (3rd ed., pp. 17–44). USA: Messachusetts Institute of Technology.

Lee, Y. H., Kwon, J. S., & Kim, Y. H. (1999). Guideline for the design and management of IEP Lesson plan. Korea National Institute for Special Education.

Ministry of education, science and technology (MEST) (2011). Action plan for the SMART education to make the Korea the country of the excellent human resources, Korea.

Nardi, B. A. (Ed.). (2001). Context and consciousness: Activity theory and human-computer interaction (3rd ed.). USA: Messachusetts Institute of Technology.

Park, O., & Lee, J. (2003). Adaptive instructional systems. In D. H. Jonassen (Ed.), The handbook of research for educational communications and technology (2nd ed., pp. 651–684). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods (2nd ed.). California: SAGE Publications Inc.

Preece, J., Rogers, Y., & Helen, S. (2007). Interaction design: Beyond human-computer interaction (2nd ed.). USA, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Rizzo, A., Pozzi, S., Save, L., & Sujan, M. (2005, September). Designing complex socio-technical systems: a heuristic schema based on cultural-historical psychology. Paper presented at EACE ‘05: Proceedings of the 2005 annual conference on European association of cognitive ergonomics, Chania, Greece.

Rose, D. H., & Meyer, A. (2002). Teaching every student in the digital age: Universal Design for Learning. ASCD.

Simonite, T. (2012). Sync Your Data without the Cloud. Technology Review, MIT. Retrieved from http://www.technologyreview.com/web/39772/.

Rose, D. H., Meyer, A., & Hitchcock, C. (2006). The Universally designed classroom: Accessible curriculum and digital technologies. USA, NJ: Harvard Education Press 8 Story Street.

Smith, G. E., & Throne, S. (2007). Differentiating instruction with technology in K-5 classrooms. ISTE (International Society for Technology in Education).

Subban, P. (2006). Differentiated instruction: A research basis. International Education Journal, 7(7), 935–947.

The Design-Based Research Collective. (2003). Design-based research: An emerging paradigm for educational inquiry. Educational Researcher, 32(1), 5–8.

Tomlinson, C. A. (1999). The differentiated classroom: Responding to the needs of all learners. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Tomlinson, C. A. (2000). Differentiation of instruction in the elementary grades. ERIC Digest, ED443572.

Tomlinson, C. A. (2001). How to differentiate instruction in mixed-ability classrooms (2nd ed.). Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Tomlinson, C. A. (2003). Deciding to teach them all. Educational Leadership, 61(2), 6–11.

Willis, S. & Mann, L. (2000). Differentiating instruction: Finding manageable ways to meet individual needs (Excerpt).

Winter, J. S. (1985). An Examination of individualized instruction. Education Resources Information Center, Retrieved from http://www.eric.ed.gov/PDFS/ED263720.pdf.

Wren, D. G. (2009). Performance assessment: A Key component of a balanced assessment system, Report from the Department of Research, Evaluation, and Assessment.

Yamagata-Lynch, L. C. (2003). Using activity theory as an analytical lens for examining technology professional development in schools. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 10(2), 100–119.

Yamagata-Lynch, L. C. (2007). Confronting analytical dilemmas for understanding complex human interactions in design-based research from a cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT) framework. The Journal of Learning Sciences, 16(2), 452–485.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the research fund of Hanyang University (HY-2012).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Cha, H.J., Ahn, M.L. Development of design guidelines for tools to promote differentiated instruction in classroom teaching. Asia Pacific Educ. Rev. 15, 511–523 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-014-9337-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-014-9337-6