Abstract

Background

Social capital can be conceptualised as an individual resource residing in relationships between individuals or as a collective resource produced through interactions in neighbourhoods, communities or societies. Previous studies suggest that social capital is, in general, good for health. However, there is a shortage of studies analysing the association between individual and collective social capital in relation to health amongst older people.

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to assess the relationship between municipal- and individual-level social capital and self-rated health amongst older people in Western Finland and Northern Sweden.

Method

Data were retrieved from a cross-sectional postal questionnaire survey conducted in 2010. The study included, in total, 6,838 people aged 65, 70, 75 and 80 years living in the two Bothnia regions, Västerbotten, Sweden and Pohjanmaa, Finland. The association between social capital and self-rated health was tested through multi-level logistic regression analyses with ecometric tests. Social capital was measured by two survey items: interpersonal trust and social participation.

Results

Individual-level social capital including social participation and trust was significantly associated with self-rated health. A negative association was found between municipal-level trust and health. However, almost all variation in self-rated health resided on the individual level.

Conclusions

We conclude that contextual-level social capital on a municipal level is less important for understanding the influence of social capital on health in the Bothnia region of Finland and Sweden. On the other hand, our study shows that individual-level social participation and trust have a positive and significant association with self-rated health. We suggest that other ways of defining social capital at the collective level, such as the inclusion of neighbourhood social capital, could be one direction for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

To check for robustness, we tried a number of alternative ecometrics specifications: (1) without accounting for “difficulty” bias and (2) a two-level model that uses the same individual-level social capital variables as are later used in the substantive models. For all specifications, we also performed sensitivity checks for the number of integration points and the adaptive quadrature methods employed in GLLAMM vis-à-vis the Stata command xtmelogit (the latter command results in Empirical Bayes modal predictions instead of the posterior means reported by GLLAMM). The municipal-level social capital variables resulting from these ecometrics analyses all correlate very highly with each other, and the results in the substantive models (Table 3) are comparable to the reported results. Thus, our results are robust to a variety of alternative specifications and estimation methods. This corresponds to earlier research (see footnotes 12 and 14 in [41]).

We compared the model fits for alternative specifications of these control variables, such as a categorical predictor of a variety of income levels. Model fit was optimal using the reported specification, and model outcomes in Table 3 are substantively similar.

The estimated equation mimics the ecometrics multi-level model. Y ij takes on a value of unity if a respondent i reports high health in municipality j, with Y ij = 0 if not. Then, m ij is the probability that Y ij = 1, and the log-odds (η ij ) of this probability is estimated as the two-level model: η ij = γ + γ 1 X ij + γ 2 Z j + u j + ε ij . In this example, we only introduce two covariates, X ij and Z j , although we, of course, introduce more covariates in each model (see Table 3). The γ is the grand-mean of self-rated health across all municipalities; X ij is an individual-level predictor (which has a different value for each individual i in municipality j), and γ 1 reflects the parameter estimate of that predictor; similarly, Z j is a municipality-level predictor and γ 2 refers to the parameter estimate of this predictor; u j refers to municipality-level random effect and ε ij refers to residual error. In several explorative models, we tested for random coefficients and cross-level interactions. Analytically, random coefficients are modelled by introducing a new interaction term between a specific covariate and group-level residuals of the slope of the individual explanatory variables. Cross-level interactions add the interaction term between individual-level and municipality-level covariates.

References

Kawachi I. Health by association? Social capital, social theory, and the political economy of public health. Commentary: reconciling the three accounts of social capital. Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33(4):682–90.

De Silva MJ, McKenzie K, Harpham T, Huttly SRA. Social capital and mental illness: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(8):619–27.

Nyqvist F, Forsman AK, Giuntoli G, Cattan M. Social capital as a resource for mental well-being in older people: a systematic review. Aging Ment Health. 2012. doi:10.1080/13607863.2012.742490.

Almedom AM. Social capital and mental health: an interdisciplinary review of primary evidence. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(5):943–64.

Islam MK, Merlo J, Kawachi I, Lindström M, Gerdtham U. Social capital and health: does egalitarianism matter? A literature review. Int J Equity Health. 2006;5(1):3. doi:10.1186/1475-9276-5-3.

Kim D, Subramanian SV, Kawachi I. Social capital and physical health: a systematic review of the literature. In: Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Kim D, editors. Social capital and health. New York: Springer; 2008. p. 139–90.

Gray A. The social capital of older people. Ageing Soc. 2009;29(1):5–31.

Walker A. A strategy for active ageing. Int Soc Sec Rev. 2002;55(1):121–39.

World Health Organisation. Active ageing: a policy framework. Geneva: WHO; 2002.

Putnam RD. Making democracy work: civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1993.

Putnam RD. Bowling alone: the collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon & Schuster; 2000.

Hooghe M, Stolle D. Generating social capital: civil society and institutions in comparative perspective. New York: Palgrave Macmillan; 2003.

Woolcock M. The place of social capital in understanding social and economic outcomes. ISUMA Can J Pol Res. 2001;2(1):1–17.

Bourdieu P (1986) The forms of social capital. In: Richardson J, editor. Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education. New York: Greenwood. p. 241–8

Coleman JS. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am J Sociol. 1988;94:S95–S120.

Lin N. Social capital: a theory of social structure and action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2001.

Engström K, Mattsson F, Jarleborg A, Hallqvist J. Contextual social capital as a risk factor for poor self-rated health: a multilevel analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(11):2268–80.

Poortinga W. Social capital: an individual or collective resource for health? Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(2):292–302.

Subramanian S, Kim D, Kawachi I. Social trust and self-rated health in US communities: a multilevel analysis. J Urban Health. 2002;79:S21–34.

Sundquist K, Yang M. Linking social capital and self-rated health: a multilevel analysis of 11,175 men and women in Sweden. Health Place. 2007;13(2):324–34.

Snelgrove JW, Pikhart H, Stafford M. A multilevel analysis of social capital and self-rated health: evidence from the British Household Panel Survey. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(11):1993–2001.

Eurostat (2012) Europe in figures. Eurostat yearbook 2011. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2011. http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/cache/ITY_OFFPUB/KS-CD-11-001/EN/KS-CD-11-001-EN.PDF Accessed 30 Jan 2012

Carlson P. The European health divide: a matter of financial or social capital? Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(9):1985–92.

Kumlin S, Rothstein B. Making and breaking social capital: the impact of welfare-state institutions. Comp Political Stud. 2005;38(4):339–65.

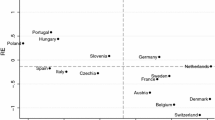

Pichler F, Wallace C. Patterns of formal and informal social capital in Europe. Eur Sociol Rev. 2007;23(4):423–35.

van Oorschot W, Arts W, Gelissen J. Social capital in Europe. Acta Sociol. 2006;49(2):149–67.

Kautto M (2001) Diversity among welfare states. Research reports 118

Esping-Andersen G. The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press; 1990.

McRae KD. Conflict and compromise in multilingual societies, Finland. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press; 1999.

Gray L, Merlo J, Mindell J, Hallqvist J, Tafforeau J, O'Reilly D, et al. International differences in self-reported health measures in 33 major metropolitan areas in Europe. Eur J Public Health. 2010. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckq170.

Cavelaars AEJM, Kunst A, Geurts J, Crialesi R, Grotvedt L, Helmert U, et al. Differences in self reported morbidity by educational level: a comparison of 11 Western European countries. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(4):219–27.

Kunst AE, Bos V, Lahelma E, Bartley M, Lissau I, Regidor E, et al. Trends in socioeconomic inequalities in self-assessed health in 10 European countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34(2):295–305.

Westman J, Martelin T, Härkänen T, Koskinen S, Sundquist K. Migration and self-rated health: a comparison between Finns living in Sweden and Finns living in Finland. Scand J Public Health. 2008;36(7):698–705.

Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38(1):21–37.

Månsson N, Råstam L. Self-rated health as a predictor of disability pension and death: a prospective study of middle-aged men. Scand J Public Health. 2001;29(2):151–8.

Idler EL, Kasl SV. Self-ratings of health: do they also predict change in functional ability? J Geront, Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1995;50B(6):S344–53.

Manderbacka K, Lahelma E, Martikainen P. Examining the continuity of self-rated health. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27(2):208–13.

Raudenbush SW, Sampson RJ. Ecometrics: toward a science of assessing ecological settings, with application to the systematic social observation of neighborhoods. Sociol Methodol. 1999;29(1):1–41.

Mohnen SM, Groenewegen PP, Völker BMG, Flap HD. Neighborhood social capital and individual health. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(5):660–7.

Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A, Pickles A. Maximum likelihood estimation of limited and discrete dependent variable models with nested random effects. J Econometrics. 2005;128(2):301–23.

Steenbeek W, Hipp JR. A longitudinal test of social disorganization theory: feedback effects among cohesion, social control, and disorder. Criminology. 2011;49(3):833–71.

Snijders T, Bosker RJ. Multilevel analysis an introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2011.

Yen IH, Michael YL, Perdue L. Neighborhood environment in studies of health of older adults: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37:455–63.

Eriksson M, Ng N, Weinehall L, Emmelin M. The importance of gender and conceptualization for understanding the association between collective social capital and health: a multilevel analysis from northern Sweden. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(2):264–73.

Portes A, Landolt P. The downside of social capital. Am Prospect. 1996;26:18–21.

Acknowledgments

The GERDA Project was supported by the Interreg-programme Botnia Atlantica, the Regional Council of Ostrobothnia, Umeå Municipality, and the GERDA Project partners, including Åbo Akademi University, Novia University of Applied Sciences, and Umeå University. The work by FN was financially supported by the Academy of Finland (project no. 250054) as part of the FLARE-2 programme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nyqvist, F., Nygård, M. & Steenbeek, W. Social Capital and Self-rated Health Amongst Older People in Western Finland and Northern Sweden: A Multi-level Analysis. Int.J. Behav. Med. 21, 337–347 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-013-9307-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-013-9307-0