Abstract

Background

The nature of the relationship between positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA) has been a topic of debate for some time. In particular, there are gaps in our knowledge of the independent effects of PA and NA on health under stress.

Purpose

The study examined the effects of a laboratory-induced stressor on the experience of PA and NA, and the effects of affect on cardiovascular (CV) reactivity and recovery.

Method

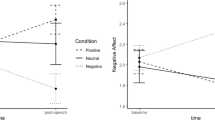

A sample of 56 female college students was randomly assigned to a public speaking (stress) task or a silent reading (control) task. Pre- and posttask PA and NA were measured using the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS Watson J Pers Soc Psychol 54:1,063-1,070, 1988). Baseline, task, and posttask cardiovascular measures were also recorded.

Results

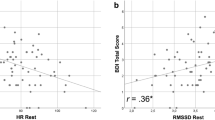

The results indicated that PA and NA responded differently to the stressor and contributed independently to the prediction of both CV reactivity and recovery. Of particular interest was the finding that higher levels of both PA and NA predicted greater CV recovery.

Conclusion

Results are discussed in light of the debate concerning the (in)dependence of positive and negative emotions and the importance of understanding the dynamics of emotions, stress, and health.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Russell JA, Carroll JM. On the bipolarity of positive and negative affect. Psychol Bull. 1999;125:611–7.

Watson D, Clark LA. Towards a consensual structure of mood. Psychol Bull. 1985;98:219–35.

Vaillant GE. Aging well: surprising guideposts to a happier life from the landmark Harvard study of adult development. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 2002.

Fredrickson BL, Levenson RW. Positive emotions speed recovery from the cardiovascular sequelae of negative emotions. Cogn Emot. 1998;12:191–220.

Zautra AJ. Emotions, stress and health. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003.

Feldman PJ, Cohen S, Lepore SJ, Matthews KA, Kamarack TW, Marsland AL. Negative emotions and acute physiological responses to stress. Annals Behav Med. 1999;21:216–22.

Maier KJ, Waldstein SR, Synowski SJ. Relation of cognitive appraisal to cardiovascular reactivity, affect, and task management. Annals Behav Med. 2003;26:32–41.

Reich JW, Zautra AJ, Davis M. Dimensions of the affect relationship: models and their implications. Rev Gen Psychol. 2003;7:66–83.

Stroud LR, Niagura RS, Stoney CM. Sex differences in cardiovascular reactivity to physical appearance and performance challenges. Int J Behav Med. 2001;8:240–50.

Speilberger CD, Gorsuch DL, Lushene RE. Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1970.

James JE, Gregg ME. Hemodynamic effects of dietary caffeine, sleep restriction, and laboratory stress. Psychophysiology. 2004;41(6):914–23.

Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54:1063–70.

Hughes JW, Stoney CM. Depressed mood is related to high-frequency heart-rate variability during stressors. Psychosom Med. 2000;62:796–803.

Blascovich J, Tomaka J. The biopsychosocial model of arousal regulation. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 1996;28:1–51.

Gregg ME, Matyas TA, James JE. A new model of individual differences in hemodynamic profile and blood pressure reactivity. Psychophysiology. 2002;39(1):64–72.

Chow SM, Ram N, Boker SM, Fujita F, Clore G. Emotion as a thermostat: representing emotion regulation using a damped oscillator model. Emotion. 2005;5(2):208–25.

Fredrickson BL, Losada MF. Positive affect and the complex dynamics of human flourishing. Am Psychol. 2005;60:678–86.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dowd, H., Zautra, A. & Hogan, M. Emotion, Stress, and Cardiovascular Response: An Experimental Test of Models of Positive and Negative Affect. Int.J. Behav. Med. 17, 189–194 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-009-9063-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-009-9063-3