Abstract

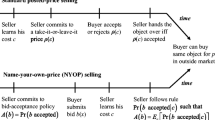

This study examines the Name-Your-Own-Price (NYOP) retailer’s information revelation strategy when competing with list-price channel. We propose an integrated economic framework focusing on the comparison of expected consumer surplus from bidding at NYOP auction and guaranteed consumer surplus from buying at a list price. We then conduct an empirical study to examine the effects of seller-supplied price information on NYOP bidding outcome (especially on expected winning probability and the number of bidders). The results of our study strongly indicate the effects of seller-supplied information on expected winning probability (as well as the expected consumer surplus) in a NYOP auction. We also illustrate the strategic implications of seller-supplied price information via a revenue simulation for the NYOP seller. Our results suggest that NYOP seller may increase his expected revenue by (1) provide only the upper bound of its threshold price when list price is high (low expected consumer surplus from buying at list price); (2) provide only the lower bound of its threshold price when list price is low (high expected consumer surplus from buying at list price); (3) provide both the upper and lower bound of its threshold price when consumer surplus of buying at list price is unknown.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The threshold price range is similar to Ding et al (2005)’s product cost, which is assumed to be uniformly distributed over a range.

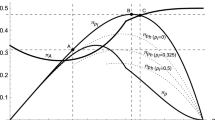

Guaranteed Consumer Surplus is the difference between consumer’s perceived value and the list price of the item, or \( GCS = v - LP \).

The expected consumer surplus of her optimal bid is the product of winning probability of optimal bid and the difference between consumer’s perceived value and the optimal bid, or \( ECS = ({v_i} - {B_i})\Pr ({B_i} \geqslant P) \), where \( \Pr ({B_i} \geqslant P) \)is the expected winning probability of bid B i .

The bidding cost was estimated to be somewhere between EUR 3.54 and 6.08 in Hann and Terwiesch (2003). Since this paper follows the single-bid policy of Priceline.com, the effects of bidding cost for one bid on consumers’ surplus is assumed to be ignorable; especially for college students whose opportunity cost of bidding time is much lower than consumers with higher income or less spare time.

A similar concept of price range mapped to probability can be found from the buyer side when they are uncertainty about their own reservation price in Wang et al. (2007).

Perceived value is defined as perceived monetary value of a product/service and is equivalent to Willingness-to-pay in Simonson and Drolet (2004). Simonson and Drolet found Willingness-to-pay of consumer products were significantly influenced by arbitrary anchors.

We used stated value instead of induced value. Although non-incentive compatible stated value may contain hypothetical bias, such a bias exists for all bidders in our study. Moreover, the focus of this study is not on optimal pricing, which requires more accurate measures of willingness-to-pay. Our primal interest is to investigate the information revelation strategy of a NYOP seller by incorporating bidder’s expected winning probability. Induced value will likely to reduce some hypothetical bias but is unlikely to change our results.

References

Bajari, P., & Hortacsu, A. (2003). The Winner’s Curse, Reserve Prices, and Endogenous Entry: Empirical Insights from eBay Auctions. Rand Journal of Economics, 34(2), 329–55.

Bapna, R., Jank, W., & Shmueli, G. (2008). Consumer Surplus in Online Auction (pp. 1–17). Article in Advance: Information Systems Research.

Budish, E. B., & Takeyama, L. N. (2001). Buy Prices in Online Auctions: Irrationality on the Internet? Economics Letters, 72(3), 325–33.

Chernev, A. (2003). Reverse Pricing and Online Price Elicitation Strategies in Consumer Choice. Journal of Consumer Psychology., 13(1/2), 51–62.

Ding, M., Eliashberg, J., Huber, J., & Saini, R. (2005). Emotional Bidders: An Analytical and Experimental Examination of Consumers' Behavior in Priceline-Like Reverse Auctions. Management Science., 51(3), 352–64.

Fay, S. (2004). Partial Repeat Bidding in the Name-Your-Own-Price Channel. Marketing Science, 23(3), 407–18.

Goeree, J. K., & Offerman, T. (2003). Competitive Bidding in Auctions with Private and Common Values. The Economic Journal, 113, 598–613.

Hann, I.-H., & Terwiesch, C. (2003). Measuring the Frictional Costs of Online Transactions: The Case of a Name-Your-Own-Price Channel. Management Science, 49(11), 1563–79.

Hinz, O., Hann, I.-H., & Spann, M. (2010). Price Discrimination in E-Commerce? An Examination of Dynamic Pricing in Name-Your-Own-Price Markets, MIS Quarterly, forthcoming.

Hinz, O., & Spann, M. (2008). The Impact of Information Diffusion on Bidding Behavior in Secret Reserve Price Auctions. Information Systems Research, 19(3), 351–68.

Kamins, M. A., Dreze, X., & Folkes, V. X. (2004). Effects of Seller-Supplied Prices on Buyers' Product Evaluations: Reference Prices in an Internet Auction Context. Journal of Consumer Research, 30, 622–8.

Levin, D., & Smith, J. L. (1994). Equilibrium in Auctions with Entry. The American Economic Review, 84(3), 585–99.

List, J. A., & Shogren, J. (1998). Calibration of the difference between actual and hypothetical valuations in a field experiment. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 37, 193–205.

Marshall, A. (1920). Principles of Economics (8th ed.). London: MacMillan and Company Ltd.

Milgrom, P. R., & Weber, R. J. (1982). A Theory of Auctions and Competitive Bidding. Econometrica, 50(5), 1089–122.

Monroe, K. B. (2003). Pricing: Making Profitable Decisions (3rd ed.). Burr Ridge, IL: McGraw-Hill/ Irwin.

Simonson, I., & Drolet, A. (2004). Anchoring effects on consumers' Willingness-to-pay and Willingness-to-accept. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(3), 681–90.

Spann, M., & Tellis, G. J. (2006). Does the Internet Promote Better Consumer Decisions? The Case of Name-Your-Own-Price Auctions. Journal of Marketing, 70, 65–78.

Von Neumann, J., & Morgenstern, O. (1944). Theory of Games and Economic Behavior. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Wang, T., Venkatesh, R., & Chatterjee, R. (2007). Reservation Price as a Range: an Incentive-Compatible Measurement Approach. Journal of Marketing Research, 44(2), 200–13.

Wang, T., Gal-Or, E., & Chatterjee, R. (2009). Understanding a Service Provider’s Decision to Employ a ‘Name Your Own Price’ Channel in the Travel Industry: An Analytical Model. Management Science, 55(6), 968–79.

Wolk, A., & Spann, M. (2008). The effects of reference prices on bidding behavior in interactive pricing mechanisms. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 22(4), 2–18.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Martin Spann

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, T., Hu, M.Y. & Hao, A.W. Name-Your-Own-Price seller’s information revelation strategy with the presence of list-price channel. Electron Markets 20, 119–129 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-010-0033-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-010-0033-z