Abstract

This paper presents archaeobotanical evidence of rice (Oryza cf. sativa L.) and black pepper (Piper nigrum) recovered from an early 2nd century AD septic pit excavated near the centre of colonia Aelia Mursa (Osijek, Croatia). Within Roman Panonnia the archaeobotanical record shows evidence of trade consisting mostly of local Mediterranean goods such as olives, grapes and figs, however, the recovery of rice and black pepper from Mursa provides the first evidence of exotics arriving to Pannonia from Asia. Preliminary thoughts on the role of these foods within the colony and who may have been consuming them are briefly discussed. The Roman period represents a time of major change in the diet of newly assimilated regions and the results here highlight the contribution that archaeobotanical remains can make to the growing discourse on the development of societies on the Roman frontier.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Roman period represents a time of major change in diet since the expansion of trade networks meant that new foods were more widely accessible in most parts of the Roman Empire. In the newly incorporated region of Pannonia, the establishment of military installations, road systems, specialised craft production, migration and the emergence of different social classes would have had a significant impact on the diet and subsistence of the local inhabitants. By examining the archaeological remains of food, important information about people and societies can be acquired since understanding food production, how and where food was obtained, as well as consumption patterns can help us approach questions regarding status and even identity. At present, archaeologists generally tend to focus on pottery typologies rather than environmental remains as indicators of food economies. As such, investigations into the role of food during the Roman period (1st–5th century AD) in eastern Croatia are relatively rare due to the limited archaeobotanical analyses conducted in the region. To date, archaeobotanical remains have only been recovered from four sites in eastern Croatia: Vitrovitica Kiškorija (Šoštarić 2015); Osijek-Silos (Starčević 2010); Sćitarjevo and Illok (Šoštarić et al. 2006). Most of the plant remains are largely associated with agriculture, i.e. cereals, pulses and weed seeds, while a small number of Mediterranean imports have also been found, including fig and olive.

From 2013 to 2015, archaeological excavations were conducted in Osijek, Croatia, revealing three phases of occupation near the centre of colonia Aelia Mursa (hereafter named Mursa), dating from the 2nd century AD to the end of the 3rd century AD. Archaeobotanical samples were collected from two septic pits dating to the first phase of the colony (120–130s) and, surprisingly, the first sample examined revealed grains of rice and black pepper. The discovery of rice and black pepper is relatively rare in Europe as a whole, so this discovery provides the first evidence of long distance exotics arriving to Pannonia from Asia. This paper therefore presents some preliminary thoughts on what the presence of rice and black pepper may suggest for the development of the new colonia of Mursa and connects in to a broader programme of research analysing archaeobotanical, zooarchaeological, ceramics and other relevant material remains from the site.

The archaeological site

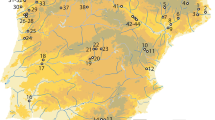

Mursa was founded by Emperor Hadrian in the AD 120/130s as a veteran colony, and is known as one of the last colonies founded ex nihilo in the history of the Roman Empire (Mócsy 1974: 119; Boatwright 2002: 36–37). Such veteran colonies were often created with the aim of integrating and developing more removed areas of the Empire, and it is likely that Mursa was founded for this purpose as well. Situated in the lower town of present day Osijek, Croatia, the site is located on the elevated right bank of the river Drava (Fig. 1), tightly embedded within the Roman Limes.

The Limes road that connected camps, forts and towers guarding the border in Pannonia followed the right bank of the Danube; however, around the confluence of the Drava and Danube marshland made the area impassable resulting in the Limes road being brought 25 km inland to Mursa. As such, Mursa was likely an important river port connecting the Drava and Danube, and although the port has yet to be located archaeologically, the Notitia Dignitatum dating to the late 4th century AD states that one of the naval bases of the Danube fleet was posted at Mursa (Not. Dign. Occ. XXXII, 52), probably to monitor and secure transport along the river Danube. In the second half of the 3rd century AD, we also see organised ecclesiastical municipalities in Pannonia, including Mursa, headed by a bishop (Mócsy 1974: 319–322; Jarak 1994; Migotti 1997; Buzov 2010.). Thus, the series of important road and river networks linking Mursa to the local military installations, as well as the wider Roman Empire, would have made the colony an important commercial, administrative and religious centre in the region (Domić Kunić 2012: 37, 44; see also Pinterović 1978). However, further suppositions about the status of Mursa within the Empire are limited from ancient texts, so only through archaeological evidence can we begin to explore aspects of the socioeconomic status of the town and its inhabitants.

Excavations conducted in 2014–2015 at Park Kraljice Jelene Kosače, Osijek (OS-KOS) revealed a crossing of two roads near the centre of Roman Mursa. Excavations also exposed the corners of two city blocks (insula A and B), where remains of commercial activities were revealed. The excavation showed three separate phases of development within this part of the city. In phase 1, dating from the founding of the colony in the 120/130s to second half of the 2nd century, the towns’ buildings were constructed entirely of wood. However, by phase 2 (end of the 2nd century AD), these wooden structures were replaced by solid buildings of brick and stone. During the 3rd century AD, a 3rd phase in which civic installations and building alterations were carried out can also be observed.

The archaeobotanical evidence

During excavations, two large (Fig. 2) and two small septic pits were discovered from the first phase of the colony in the SW corner of the larger wooden structure that existed for insula A. All four pits were rectangular, up to 2 m deep and filled with pottery, mostly kitchen and tablewares, animal bones and earth that contained organic material. The archaeological remains so far suggest that they represent the rubbish from a kitchen within a large residence, a guesthouse or a tavern. The upper layers of the cesspits contained burnt earth and charcoal which are believed to have come from the wooden building of insula A, which was destroyed by fire.

In total, 16 archaeobotanical samples were collected from the septic pits, equalling approximately 850 l of sediment. The samples were then processed through bucket flotation using a mesh of approximately 500 μm and examined using a stereo zoom microscope (5-45×). To date, only sample 391 (SJ391) has been sorted and the plant remains identified. All plant remains were carbonised, with good overall preservation (i.e. the seed epidermis was nearly intact with only slight signs of distortion caused by the fire).

Five rice grain fragments were recovered from sample 391 (Fig. 3a). Rice caryopses are quite distinct, characterised by long, laterally compressed grains with an oblique tip and ridges running their length. However, the morphological characteristics of Asian (Oryza sativa L.) and African (Oryza glaberrima Steud.) rice grains are quite similar, thus the recovery of spikelet bases are the best species indicator. Unfortunately, no spikelet bases have been identified so far from the assemblage; therefore, the grains have been identified as Oryza cf. sativa, as this is more likely, based on the recorded trade between the Roman world and South Asia.

Two carbonised black peppercorns (Piper nigrum) were also identified from sample 391, characterised by the prominent ridges and their almost hexagonal appearance (Fig. 3b).

Sample 391 also contained hundreds of other cultivated and wild plants (Fig. 4). Of the cereals, barley (Hordeum vulgare ssp. vulgare) is the most common, with a small number of naked wheat (Triticum turgidum ssp. durum/Triticum aestivum), rye (Secale cereale) and millet (Panicum miliaceum) grains being identified. Other crops such as pea (Pisum sativum), lentil (Lens culinaris), garlic (Allium sativum) and olive (Olea europea), along with a large number of grape (Vitis vinifera) and fig (Ficus carica) seeds were also recovered. In addition, cereal/ruderal weeds were identified, including corncockle (Agrostemma githago), cleavers (e.g. Galium aparine) and various grasses (e.g. Bromus, Lolium).

The arrival of rice and black pepper to Europe

Black pepper (hereafter named pepper) refers to the dried mature fruits or berries of the tropical, perennial woody climbing plant Piper nigrum L., originating in the tropical forests bordering the Malabar Coast, southwest India. Asian rice, originating in China c. 6500–6000 cal BC (Silva et al. 2015) and India c. 2000 years later (Fuller 2011), was traded across Asia from the 3rd millennium BC and from western Asia from the 1st century AD (Fuller et al. 2010).

The early history of the rice and pepper trade to the west is sporadic, but was likely monopolised by the Arabs on a small scale until the Romans conquered Egypt c. AD 40, when trade expanded considerably (Ravindran 2000:6; Burstein 2002; Amigues 2005). The main route of trade with Asia seemed to have been via the Red Sea to Egypt (Thapar 1992). Archaeological evidence from Quseir al-Qadim and Berenike on the Red Sea suggests that both pepper and rice were traded through the ports during the 1st to early 3rd centuries AD (Cappers 2006; Van der Veen 2011; Van der Veen and Morales 2015). Even the Periplus Maris Erythraei, written around the middle of the 1st century AD, describes the east-west trade route running from Egypt and the large ships that were sent on account of the large quantities of pepper and malabathrum traded (Schoff 1912:44). It is suggested that pepper was traded (ground or as whole peppercorns) to Rome where, after AD 92, it was stored in special warehouses called horrea piperataria near the Via Sacra (Warmington 1928: 183). If un-ground, the peppercorns would have been crushed in pepper mills (molae piperatariae) and mortars and sold in paper packets in the Vicus unguentarius (ibid.).

How did rice and pepper arrive in Mursa?

By the time Mursa was founded, Pannonia was already strengthened through the construction of roads and by fortifying waterways. The oldest trade routes through which luxury goods were most likely brought into Pannonia were via roads that connected the Italian ports of Tergeste and, particularly, Aquileia (Northern Italy) (cf. Domić Kunić 2012: 43; Petrović 2013) (Fig. 5). Aquileia was founded as a colony and commercial hub for trade between important centres such as Corinth, Alexandria, Nicomedia, Italy and the Balkan-Danubian region (Brusin 1953–54; Panciera 1957; Bounegru 2014). In the early 1st century AD, Strabo (5.1.10) mentions the trading post of Aquileia as the location where Illyrian tribes would trade slaves, cattle and hides for products such as wine and olive oil. Even when the Balkans became part of the Empire, strong links between Pannonia and Aquileia continued (Humphries 1998). Between Aquileia and Mursa, the site of Rabeljča in eastern Slovenia highlights these trade links since evidence of dates (Phoenix dactylifera), pomegranates (Punica granatum) and jujube (Ziziphus jujube) from the Middle East were found in Roman graves there (Culiberg 1999).

Other routes through which rice and pepper could have been traded include the roads that connected southern Pannonia with the east Adriatic coast, which already existed and were used for trade by the 1st century AD (Bojanovski 1974: 192–202; Migotti 2000; Kovács 2014: 46). Another route, which is rarely explored, is that along the Lower Danube. In particular, the Black Sea is an area where several large and wealthy city ports existed that facilitated trade between other major ports of the Empire, as well as connecting to the Silk Road (McLaughlin 2010: 90–1).

Society, culture and food in Roman Mursa

The unique discovery of rice and pepper dating to the 2nd century AD brings to the fore questions on who was consuming them, whether there was a great demand for such items and what this may say about society and culture in Mursa.

Uses and economic status of rice and black pepper during the Roman period

The status of pepper and rice in Roman Europe is suggested to be one of ‘luxury’ as such products came from a far and distant land and were therefore difficult to get hold of, making them prestige items only enjoyed by the upper echelons of society (e.g. Van der Veen and Morales 2015). For example, Pliny (NH 12.14) complains about such excesses, as the need to import such luxury items from India required large quantities of gold and silver coinage to be sent in exchange for the spice. Pepper is also mentioned in nearly every recipe of Apicius’ De re coquinaria dating to the 3rd century AD, which may indicate both its high status in society, and a fashion for heavily spiced foods (Warmington 1928: 182; Déry 1996).

Archaeologically, peppercorns and rice are rare, supporting theories that they were ‘luxury’ or high status food items. Their remains are usually found associated with military camps or towns, particularly along the European Limes (Knörzer 1966, 1970:13,28; Furger 1995; Zach 2002:104–5; Livarda and Van der Veen 2008; Nesbitt et al. 2010:329; Livarda 2011). The contexts range from city sewers to military hospitals and sacrificial pits. For example, the Roman military encampment near Dusseldorf, Germany, produced 196 charred grains of rice dating to the first quarter of the 1st century AD (Knörzer 1966, 1970; Konen 1999). These were recovered from a building identified as a military hospital, along with a range of other possible medicinal plants, suggesting that rice was valued for its medicinal properties. This is also regularly seen in various Roman pharmaceutical and medical treatises. For instance, Celsus (Book II, Cap. XXIII-XXIV) notes that soaked rice is good for thickening phlegm and the stomach.

Yet, other finds are less substantial. At Mogontiacum (Mainz), the capital of Germania Superior, a single possible grain of rice (cf. Oryza sativa) was found in a sacrificial pit at the temple of Isis and Magna Mater dating to the second half of the 1st century AD or slightly later (Zach 2002). Mineralised black peppercorns have also been found from the Cardo V sewer in Herculaneum (Rowan 2014), while in Roman London pepper has been found at a few excavations, including in a cremation and in the early trading settlement of Southwark (Cowan et al. 2009:102). Overall, it has been suggested that these finds may indicate certain privileges being bestowed onto military camps and towns (Livarda 2011). How these items were used may have therefore ranged from being consumed as part of a ‘luxury’ meal, being incorporated in an army first aid kit or integrated within important rituals.

However, at the height of the eastern trade the largest export in tonnage from India to the Mediterranean world was likely pepper, which may have actually reduced its market value, allowing the average person to procure it at a reasonable price (Warmington 1928:233). Pliny (NH 12.14.28) even notes that black pepper was cheaper, at four denarii per pound, than white pepper (seven denarii per pound) and long pepper (15 denarii per pound). While these observations come from markets in Rome, at the fort of Vindolanda along Hadrian’s Wall, a recovered writing tablet shows that a low ranking soldier was able to purchase pepper (although no quantities were listed) for the small sum of 2 denarii near the end of the 1st century AD (Tab. Vindol. II. 184). The frequent mention of pepper in ancient texts on food, trade, medicine and rituals indicates that these commodities were relatively well known by the Roman populations (Sidebotham 2011:250). In addition, the absence of pepper from the Alexandrian tariff (codified c. AD 176–180), which listed spices subject to the 25% import duty, may imply that it was a staple rather than a luxury item (Tomber 2008:55).

Socio-cultural change in Pannonia: the influence of the army

The role of ‘elites’ has often been suggested as a key driver in the importation of exotic food plants to the frontier (Livarda 2011); however, exactly who comprised the upper strata of Mursan society is still unclear since there is little epigraphic evidence or signs of any wealthy burials. Instead, what we do know is that Mursa was established as a veteran colony by Hadrian, and that soldiers honourably discharged after the end of their military service were settled in less-populated areas to strengthen the local infrastructure (Tacitus, Ann. 14.27.2). Upon retirement, veterans received either a piece of land (misso agrarian) or a cash payment (misso nummaria) to start their civilian life (Wesch-Klein 2007:439). Many veterans possessed multiple skills, including specialisations in crafts, technologies and medicine (Wesch-Klein 2007:444). This would have meant that as Mursa was settled, skilled individuals, possibly perceived as a provincial ‘middle class’, could have gained access to a range of imported goods that had been previously restricted to societies ‘elite’(cf. Mayer 2012: 215).

The veterans would have been highly regional in origin with their own identity embedded within the common military culture that likely developed around commonalities in dress, training, language (Latin) and rituals (cf. James 1999; Wells 1999). This would have allowed for individual preferences to be incorporated into military life, such as preferences for certain foodstuff (e.g. King 1999). Many officials, soldiers and veterans would have been well paid and enjoyed certain privileges (James 1999; Mattingly 2006:166), but little can be found in literary sources on the provision of exotic foods to the army. Nevertheless, archaeologically, it is clear that exotic plants have been identified from military contexts (e.g. Bakels and Jacomet 2003; Livarda 2011). For example, black peppercorns were recovered from the legionary camp in Oberaden (Kučan 1992; Bakels and Jacomet 2003), while at Nijmegen, a pot with pickled thrush breasts was found (Carroll 2005:368), which suggests that legions were exposed to different luxury and exotic foodstuffs.

These demands for certain food items are likely to have resulted in distinct changes in trade and supply demands along the Danube Limes (Mócsy 2015:120). Mursa was therefore uniquely positioned to become a centre of logistics through which goods could be distributed to the frontier (Pinterović et al. 2014): this cooperation of supplying goods between the army and nearby civil settlement is seen elsewhere in the Empire (Adams 1999). The Roman army could have then played a role in the dissemination of certain foodstuffs into Pannonia, while the veterans who settled in Mursa may have continued their original dietary habits, possibly exploiting army supply networks in the region. Thus, Mursa would have been only a part of a much broader distribution system in the region supplying, among other things, ‘exotic/luxury’ foodstuffs to the town and potentially to the army.

Conclusion

The discovery of rice and black pepper from an early 2nd century septic pit within Roman Mursa is the first archaeobotanical evidence of long distance exotics being imported into Pannonia. Unfortunately, the discovery of rice and black pepper in Mursa raises more questions than can be answered at this stage, such as who was consuming these foodstuffs, whether there was a great demand for such items and what this may say about society and culture in Mursa. Whether its presence can be seen as a ‘Roman’ food or as the adoption of ‘Roman’ culture is highly debatable and needs further examination, but its presence does show the exploitation of the wider Roman food system and the evolution of diets in the region. The many trade routes leading into Mursa also make it difficult to determine how the plants arrived to the town, but the presence of the military and the fact that Mursa was a veteran colony are likely to have been key drivers in the spread and/or acquisition of such exotics in the town. Further archaeological and archaeobotanical analyses over the coming years will hopefully help to elucidate further on some of these questions, but it is important to stress the contribution that archaeobotanical remains can make to the growing discourse on the development of societies on the Roman frontier.

References

Adams CEP (1999) Supplying the Roman Army: Bureaucracy in Roman Egypt, in A. Goldsworthy & I. Haynes (ed.). The Roman Army as a Community. J Roman Archaeol 34:119–126

Amigues S (2005) Végétaux et aromates de l'Orient dans le monde antique. Topoi 12(13):359–383

Bakels C, Jacomet S (2003) Access to luxury foods in Central Europe during the Roman period: the archaeobotanical evidence. World Archaeol 34:542–557

Boatwright MT (2002) Hadrian and the cities of the Roman Empire. Princeton, Princeton University Press

Bojanovski I (1974) Dolabelin sistem cesta u rimskoj provinciji Dalmaciji (Dolabellae systema viarum in provincia romana Dalmatia), Djela ANUBiH 47/2

Bounegru O (2014) The Black Sea area in the trade system of the Roman Empire. Euxeinos 14:8–16

Brusin JB (1953-1954) Orientali in Aquileia romana, Aquileia Nostra 24-25, cc. 55-70

Burstein SM (2002) Kush, Axum and the ancient Indian Ocean trade. In: Bács TA (ed) A Tribute to Excellence: Studies Offered in Honor of Ernö Gaál, Ulrich Luft, and Lásló Török (Studia Aegyptiaca XVII). Chaire d'Egyptologie de l'Université Eotvos Lorand, Budapest, pp 127–137

Buzov M (2010) The topography and the archaeological material of the early Christian period in Continental Croatia. Classica et Christiana 5:299–334

Cappers RTJ (2006) Roman foodprints at Berenike. Los Angeles, Cotsen Institute of Archaeology

Carroll M (2005) The preparation and consumption of food as a contributing factor towards communal identity in the Roman army. In: Visy Z (ed) Limes XIX. Acts of the XIXth International Congress of Roman Frontier Studies. Pécs, University of Pécs Press, pp. 363–372

Cowan C, Seeley F, Wardle A, Westman A, Wheeler L (2009) Roman Southwark, Settlement and Economy: excavations in Southwark, 1973–91 (Monograph 42). Museum of London Archaeology, London

Culiberg M (1999) Palaeobotany in Slovene Archaeology. Arheološki vestnik 50:323–331

Déry CA (1996) The art of Apicius. In: Walker H (ed) Cooks and other people: Devon, Prospect Books, pp. 111-117

Domić Kunić A (2012) Literary sources before the Marcomannic wars. In: Migotti B (ed) The archaeology of Roman Southern Pannonia (British Archaeological Reports International Series 2393) Oxford, Archaeopress, pp. 29–69

Fuller DQ (2011) Pathways to Asian civilizations: tracing the origins and spread of rice and rice cultures. Rice 4:78–92

Fuller DQ, Sato Y, Castillo C, Qin L, Weisskopf AR, Kingwell-Banham EJ (2010) Consilience of genetics and archaeobotany in the entangled history of rice. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 2:115–131

Furger AR (1995) Vom Essen und Trinken im römischen Augst - Kochen, Essen und Trinken im Spiegel einiger Funde. Archäologie der Schweiz 8:168–184

Humphries M (1998) Trading gods in northern Italy. In: Parkins H, Smith C (eds) Trade, traders and the ancient city. Routledge, London, pp 203–224

James S (1999) The community of the soldiers: a major identity and centre of power in the Roman empire. In: Baker P, Jundi S, Witcher R (eds) TRAC 98: proceedings of the eighth annual theoretical Roman archaeology conference, Leicester 1998. Oxbow, Oxford, pp 14–25

Jarak M (1994) The history of early Christian communities in Continental Croatia. In: Demo Ž (ed), Od Nepobjedivog sunca do Sunca pravde. Rano kršćanstvo u kontinentalnoj Hrvatskoj. Zagreb, Arheološki muzej, pp. 17-39

King A (1999) Diet in the Roman world: a regional inter-site comparison of the mammal bones. J Roman Archaeol 12:168–202

Knörzer K-H (1966) Über Funde römischer Importfrüchte in Novaesium (Neuss/Rh’). Bonner Jahrbücher 166:433–443

Knörzer K-H (1970) Römerzeitliche Pflanzenreste aus Neuss. Limesforschungen 10, Novaesium 4. Berlin, Verlag Gebr. Mann

Konen H (1999) Reis im Imperium Romanum: Bemerkungen zu seinem Anbau und seiner Stellung ah Bedarfs- und Handelsartikel in der ròmischen Kaiserzeit. Münstersche Beiträge zur Antiken Handelsgeschichte 18:23–47

Kovács P (2014) A history of pannonia during the principate (Antiquitas. Reihe 1, Abhandlungen zur alten Geschichte, Band 65). Bonn: Dr. Rudolf Habelt GMBH

Kučan D (1992) Die Pflanzenreste aus dem römischen Militärlager Oberaden. In: Kühlborn J-S, von Schnurbein S (eds) Das Römerlager in Oberaden III: Die Ausgrabungen im nordwestlichen Lagerbereich und weitere Baustellenuntersuchungen der Jahre 1962–1988 (Bodenaltertümer Westfalens 27). Münster, Aschendorff, pp 237–281

Livarda R (2011) Spicing up life in North-western Europe: exotic food plant imports in the Roman and Medieval world. Veg Hist Archaeobotany 20:143–164

Livarda A, Van der Veen M (2008) Social access and dispersal of condiments in North West Europe from the Roman to the medieval period. Veg Hist Archaeobotany 17(Suppl 1):201–209

McLaughlin R (2010) Rome and the distant east: trade routes to the ancient lands of Arabia, India and China. Bloomsbury, London

Mattingly DJ (2006) An imperial possession. Britain in the Roman Empire, 54 BC–AD 409. London, Allen Lane

Mayer E (2012) The ancient middle classes: urban life and aesthetics in the Roman Empire, 100 BCE-250 CE. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Migotti B (1997) Evidence for Christianity in Roman Southern Pannonia (Northern Croatia): a catalogue of finds and sites (British Archaeological reports International Series 684). Archaeopress, Oxford

Migotti B (2000) Prilog poznavanju putova trgovine između Dalmacije i Panonije. Opvscvla Archaeologica 23-24:195–202

Mócsy A (1974) Pannonia and Upper Moesia. A history of the middle Danube provinces of the Roman Empire. London, Routledge

Mócsy A (2015) Pannonia and Upper Moesia (Routledge Revivals). A history of the middle Danube provinces of the Roman Empire. London, Routledge

Nesbitt M, Simpson SJ, Svanberg I (2010) History of rice in Western and Central Asia. In: Sharma SD (ed) Rice: Origin, Antiquity and History. Enfield. Science Publishers, pp 308–340

Panciera S (1957) Vita economica di Aquileia in étà Romana. Aquileia, Associazione Nazionale per Aquileia

Petrović V (2013) Terrestrial communications in the late antiquity and the Early Middle Ages in the Western part of the Balkan Peninsula. In: Rudić S (ed) The world of the Slavs: studies on the East, West and South Slavs: civitas, oppidas, villas and archeological evidence (7th to 11th Centuries AD). Beograd, Istorijski institute, pp 235–287

Pinterović D (1978) Mursa i njeno područje u antičko doba. Osijek, Centar za znanstveni rad Jugoslavenske akademije znanosti i umjetnosti

Pinterović D, Mutnjaković A, Pehnec S (2014) Mursa. Zagreb, Hrvatska akademija znanosti i umjetnosti

Šoštarić R (2015) Biljni ostaci iz antičkog i srednjovjekovnog naselja na lokalitetu Virovitica Kiškorija Jug. In: Jelinčić Vučković K (ed) Rimsko selo u provinciji Gornjoj Panoniji: Virovitica Kiškorija Jug (Monographiae Instituti archaeologici 7). Zagreb, Institut za Archeologiju, pp 311–326

Šoštarić R, Dizdar M, Kušan D, Hršak V, Mareković S (2006) Comparative analysis of plant finds from early Roman graves in Ilok (Cuccium) and Šćitarjevo (Andautonia), Croatia—a contribution to understanding burial rites in Southern Pannonia. Collegium Antropologicum 30:429–436

Starčević S (2010) Karbonizirani biljni ostaci antičkog lokaliteta Osijek—Silos. University of Zagreb, Dissertation

Ravindran PN (2000) Black pepper. Harwood Academic, Amsterdam

Rowan E (2014) Roman diet and nutrition in the Vesuvian region: a study of the bioarchaeological remains from the Cardo V sewer at Herculaneum. University of Oxford, Dissertation

Schoff WH (1912) The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: travel and trade in the Indian ocean by the merchant of the first century. Longmans, Green and Co, New York

Sidebotham SE (2011) Berenike and the ancient maritime spice route. University of California Press, Berkeley

Silva F, Stevens CJ, Weisskopf A, Castillo C, Qin L, Bevan A, Fuller DQ (2015) Modelling the geographical origin of rice cultivation in Asia using the rice archaeological database. PLoS ONE 10. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0137024

Thapar R (1992) Black gold: South Asia and the roman maritime trade. South Asia. J South Asian Stud 15:1–27

Tomber R (2008) Indo-Roman Trade: from pots to pepper. Duckworth, London

Van der Veen M (2011) Consumption, Trade and Innovation: Exploring the Botanical Remains from the Roman and Islamic Ports at Quseir al-Qadim, Egypt. Frankfurt, Africa Magna Verlag

Van der Veen M, Morales J (2015) The Roman and Islamic spice trade: new archaeological evidence. J Ethnopharmacol 167:54–63

Warmington EH (1928) The commerce between the Roman Empire and India. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Wells PS (1999) The Barbarians speak: how the conquered peoples shaped Roman Europe. Princeton, Princeton University Press

Wesch-Klein G (2007) Recruits and veterans. In: Erdkamp P (ed) A companion to the Roman army. Wiley-Blackwell, London, pp 435–450

Zach B (2002) Vegetable offerings on the Roman sacrificial site in Mainz, Germany – short report on the first results. Vegetation History and Archaeobotany 11:101–6

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Hrvoje Kalafatić for helping with the flotation of the archaeobotanical samples. I would also like to thank Matthew J. Mandich and the two anonymous referees who provided valuable comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Reed, K., Leleković, T. First evidence of rice (Oryza cf. sativa L.) and black pepper (Piper nigrum) in Roman Mursa, Croatia. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 11, 271–278 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-017-0545-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-017-0545-y