Abstract

Background

The objective of this paper is to analyze the current status of monkeypox worldwide. In the face of this public health threat, our purpose is to elucidate the clinical characteristics and epidemiology of monkeypox, the developmental progress of monkeypox-related drugs and the vaccines available.

Data sources

The literature review was performed in databases including PubMed, Science Direct and Google Scholar up to July 2022.

Results

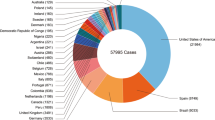

Since May 2022, the World Health Organization has reported more than 45,000 confirmed cases from 92 nonendemic countries, including nine deaths. Although some women and children have been infected so far, most cases have occurred among men who have sex with other men, especially those with multiple sexual partners or anonymous sex.

Conclusions

Pediatric monkeypox infection has been associated with a higher likelihood of severe illness and mortality than in adults. Severe monkeypox illness in pediatrics often requires adjunctive antiviral therapy. It is crucial for all countries to establish sound monitoring and testing systems and be prepared with emergency preparedness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Monkeypox is a rare, sporadic, smallpox-like zoonotic infectious disease caused by monkeypox virus, an orthopoxvirus genus of the Poxviridae family [1, 2]. The disease frequently occurs in Central and West African countries, especially the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where it is considered endemic [3, 4]. Early research indicates that human infection with monkeypox virus occurs most commonly in the 5- to 9-year-old age group, particularly in small villages where the children hunt and eat squirrels and other small mammals [5]. In the last few years, the United Kingdom, the United States, Singapore and Israel have reported the existence of imported cases in individuals with an African travel history [6,7,8]. Monkeypox has recently grown to be a global concern, as the World Health Organization reported over 45,000 confirmed and suspected cases (as of August 29, 2022) in more than 90 countries in Europe, the Americas, the Eastern Mediterranean, the Western Pacific and Southeast Asia [9, 10]. Moreover, the number of cases is expected to continuously increase. Significantly different from the past, the vast majority of cases recently reported have no established travel links with endemic areas, involve community transmission and include a small number of women and children [most of the original cases occurred in men who have sex with other men (MSM)] [11], indicating that cases in children may be more frequently reported in the future.

The uncertainty of monkeypox epidemic control and the risk of transmission at the social level have increased the possibility of cross-border spread and onward transmission of monkeypox disease. Therefore, this manuscript not only briefly introduces the family Poxviridae but also reviews the clinical manifestations, epidemiology, drug treatment and vaccine application, prevention and control strategies of monkeypox in detail.

Family Poxviridae

The virus that causes monkeypox, monkeypox virus (MPXV), was first discovered in 1958 as the source of infection that caused an outbreak of pustular rash illness in cynomolgus monkeys shipped from Africa to Copenhagen, Denmark, for research purposes. Hence, the name “monkeypox” [12,13,14,15]. Later, in 1970, human monkeypox was discovered in an infant who had presented with smallpox-like eruptions in the DRC [16]. Two main clades of human MPXV have been identified: the Central African strains and the West African (WA) strains, the former being more virulent in nonhuman primates. Evidence indicates that the lethality rates are 10.6% and 3.6% for the strains, respectively [17, 18]. MPXV is a double-stranded DNA virus of the orthopoxvirus (OPXV) genus of the family Poxviridae [19, 20]. Poxviridae are classified into two subfamilies: Entomopoxvirinae and Chordopoxvirinae [21]. There are four genera of the subfamily Chordopoxvirinae that can induce human diseases. Among them, viruses from the genera orthopoxvirus, parapoxvirus and yatapoxvirus harbor zoonotic potential [22]. The genus OPXV mainly contains viruses that infect humans: monkeypox virus, cowpox virus, vaccinia virus, and smallpox virus. According to previous studies, gene homology within OPXV can reach 90% based on immune cross protection and cross reactivity [23]. The cross protection allows individuals who had been infected by any member of the genus to be protected against an infection with another virus from the same genus. This is the scientific basis behind Edward Jenner’s cowpox inoculations and vaccinia virus Tian Tan strain isolated in China protecting against variola virus (VARV) [24,25,26].

Clinical presentation

In most cases, monkeypox is a rare but potentially serious viral illness that usually begins with a flu-like illness and swollen lymph nodes and progresses to a widespread rash on the face and body [27]. Monkeypox and smallpox have similar appearance, distribution and pathological progression; however, monkeypox is often less severe [2, 14]. The severity of disease depends on the patient’s age and comorbidities, and case fatality in monkeypox has been reported up to 15%, with younger children being at highest risk [28]. In 1987, pronounced lymphadenopathy was identified as the only clinical sign differentiating monkeypox from smallpox and chickenpox (varicella) [29].

In general, adults or children infected with monkeypox will experience three stages: incubation, prodromal, and rash periods. The incubation period of monkeypox is usually 7–14 days, but it can be longer (5–21 days), with symptoms and signs lasting two to five weeks [30]. Notably, using vaccination after exposure to monkeypox (within four days) given the long incubation period (versus COVID, where the incubation period is shorter) is essential for children and adults [31]. The following prodromal features include fever, muscle aches, headache, backache, sore throat and swollen lymph nodes, followed by a broad, well-circumscribed rash typical of an eccentric pattern. Within one to three days (sometimes longer) after the patient develops fever, the patient develops skin rash, which usually starts from the face and then spreads to other parts of the body. These rashes then go through five stages: macular stage, papule phase, vesicular phase, pustular phase, and finally enter the scab phase [32, 33]. Patients with monkeypox have traditionally been considered infectious until all the lesions have crusted.

However, since May 2022, monkeypox cases in many countries have been atypical in that the rash is starting at genital areas [34]. Available data show that 98.2% of monkeypox cases (22, 548/22954) are male, and the median age is 36 years. At present, this symptom occurs only in adults [10]. It must be noted that although the clinical manifestations of monkeypox are milder than those of smallpox, the disease can be fatal, with mortality rates ranging from 1% to 10% [1, 13, 35, 36]. Newborns, children and immunodeficient patients may face more acute monkeypox symptoms and risk of death. Moreover, severe monkeypox cases can develop complications, including skin infections, pneumonia, confusion, and eye infections, that can lead to vision loss [13]. These complications often occur in children or individuals with other comorbidities and are common in Central Africa. For example, in 2016, a case of a 4-year-old boy was reported in the DRC. The boy presented with the typical clinical manifestations described above, including low-grade fever (37.9 ℃), rhinitis, conjunctivitis, severe left-sided cervical lymphadenitis, and a nonitchy vesiculopapular rash on admission. In the following two to five days, he experienced fever up to 38.5 ℃, and the rash began to spread to cover his entire body surface, including palms, foot soles, and mucous membranes, the latter resulting in severe and painful stomatitis. Although the patient received supportive care, the skin and oral features became progressively worse, and the child died on day 12 post admission [37]. In contrast, the first case of monkeypox outside Africa occurred in the United States in 2003: a 6-year-old girl was intubated and mechanically ventilated due to encephalitis, and a 10-year-old girl had tracheal airway damage secondary to cervical lymphadenopathy and a large retropharyngeal abscess. Although one in five pediatric patients developed serious complications in the United States, no deaths occurred due to intensive medical intervention [33]. In general, the clinical symptoms of monkeypox infection in children outside Africa are milder than those in central and West African countries. The vast majority of monkeypox infections in Africa occur in children and have a very high mortality rate, which is likely an unfortunate consequence of the lack of access to medical services. In addition, different nutrition habits, health conditions and economic education levels can make a significant difference in the risk and symptoms of monkeypox infection [37, 38].

It is challenging to distinguish monkeypox, chickenpox and smallpox only according to these clinical manifestations. Reasonable laboratory diagnostic methods, such as nucleic acid amplification tests, including real-time or conventional polymerase chain reactions, to detect the unique sequence of viral DNA are also necessary for the confirmation of MPXV infection [39,40,41].

Epidemiology

Monkeypox is a viral zoonosis (a virus transmitted to humans from animals) with symptoms very similar to those seen in the past in smallpox patients, although it is clinically less severe [42]. Monkeypox has not attracted much attention since its discovery 65 years ago. In 1970, in Central Africa, a 9-month-old child from Zaire (now the DRC) became infected with MPXV, the first human infection reported in history [43,44,45]. The number of human monkeypox cases has been on the rise since the 1970s, with the most dramatic increases occurring in the DRC. The median age at presentation has increased from 4 (1970s) to 21 years (2010–2019) [46].

Regional characteristics of monkeypox

Ever since its discovery, the disease has been endemic to Central and West Africa, with sporadic, intermittent cases of monkeypox transmitted from local wildlife reported among humans. Monkeypox disease in Central Africa has clearly been proven to be transmissible between humans and can result in death. The case fatality rate is on average approximately 10% in nonvaccinated individuals. However, the number of reported human monkeypox diseases in West Africa is limited, which is comparably less severe and demonstrates less human-to-human transmission than that in Central Africa [47, 48]. In 2003, monkeypox broke out in the United States. At that time, the monkeypox epidemic was relatively large, and it spread to six states, including Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Missouri and Ohio [49]. A follow-up investigation at the time found that the monkeypox outbreak may have been linked to the importation of rodents, resulting in 47 confirmed or probable cases. Although the clinical features of most patients were milder than typically seen in Africa, nine patients were hospitalized as inpatients, and five patients were defined as being severely ill [33, 43, 50, 51]. Between 2018 and 2021, adults traveling from Nigeria were diagnosed with monkeypox in Israel, the United Kingdom, Singapore, and the United States; however, all of them had a travel history to endemic regions of Central and West Africa [7, 46]. Compared with the past, monkeypox cases occurred suddenly and unexpectedly in several countries in May 2022, and these cases have no direct connection with areas that have experienced monkeypox for a long time, suggesting that monkeypox is much more likely to go out of Africa.

Infectious sources and transmission routes of monkeypox

The host range and pathogenesis of MPXV are unknown. Rodents are likely to be potential hosts. In addition to rodents, nonhuman primates and humans can be reservoirs of infection [52, 53]. The occurrence of monkeypox in humans is more due to animal-to-human transmission than to limited human-to-human transmission [54, 55]. The main route of transmission is contact transmission. In Africa, where nutrition is poor, contact with live and dead animals through hunting and consumption of wild game or bush meat is a known risk factor for children. Children in countries outside Africa, however, were probably infected by MPKV through exposure to imported pet rodents [56]. While it is unclear where the current monkeypox cases originated, it is possible that through its evolution, MPXV increased its transmissibility among humans. Reports of women's cases herald children also in high-risk settings.

Drugs and vaccines

Although there is currently no standard-of-care treatment for monkeypox and it can only be managed through supportive care and symptomatic treatment, the emergence of smallpox antiviral drugs with poxvirus activity has been used against monkeypox [59]. Antiviral drugs currently used for smallpox mainly include tecovirimat (ST-246 or TPOXX) and brincidofovir, which were approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2018 and 2021, respectively, for the treatment of smallpox under the Animal Rule [60, 61]. In addition, both oral drugs have demonstrated efficacy against other orthopoxviruses (including monkeypox) in multiple animal models [62,63,64]. Tecovirimat and brincidofovir have been shown to be safe and well tolerated at the recommended human doses in human clinical safety trials [65]. Tecovirimat prevents the spread of the virus by inhibiting the function of the major envelope protein VP37, preventing the virus from leaving the infected cell. Tecovirimat is primarily indicated for the treatment of adults and pediatric patients weighing at least 13 kg [66, 67]. In comparison, Brincidofovir achieves its antiviral effect by integrating into the viral DNA, thereby inhibiting the action of viral DNA polymerase. Brincidofovir has stable absorption and can be used in very low birth weight infants and even neonates in emergency situations [60, 61, 68]. Additionally, other antiviral drugs, such as cidofovir and vaccinia immune globulin, if necessary, can be used in combination with brincidofovir and tecovirimat for the treatment of monkeypox disease [69] (Table 1). Notably, neither drug has been studied in human efficacy trials, particularly in the treatment of human monkeypox [70]. There is currently no effective treatment except for early vaccination after exposure to the virus.

Furthermore, preexposure vaccination with smallpox vaccines has been shown to be protective in multiple animal models against a variety of OPXV challenges, and it has been estimated to provide 85% cross protection against monkeypox infection [17, 55]. Currently, the second-generation licensed smallpox vaccine ACAM2000 (a live‐attenuated replicating vaccine) and the third-generation vaccine JYNNEOS (a replication-deficient MVA vaccine) are two FDA‐approved vaccines that can prevent monkeypox. However, ACAM2000 is not suitable for immunocompromised individuals due to its high toxicity [71, 72]. The youngest reported case was a child with a parent who received ACAM2000; 11 days later, the child was exposed to a used dressing from the parent's vaccination site, and two days later, he/she developed a “pimple-like reaction above the left eyebrow”. Similarly, inadvertent transmission of ACAM2000 may occur, including vertical transmission from mother to child, which may be fatal to the fetus or newborn. Myopericarditis was a more frequent serious adverse event with ACAM2000® than with JYNNEOS [69]. As such, it is only for use by military personnel and laboratory personnel working with OPXV in the United States but is not administered to the public [73]. The newly developed third-generation smallpox vaccine, modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA), is safe for immunocompromised individuals and has also been approved by the European Medicines Agency for the prevention of adults identified as at high risk of VARV and MPXV infection (18 years or older) smallpox and monkeypox, excluding children and infants [74]. Although MVA has demonstrated a good safety profile in phase III clinical trials, large-scale vaccination studies are still needed, and MVA has not been approved for use in the general population to prevent smallpox and monkeypox diseases. Additionally, its cost is also one of the factors to be considered [75]. In conclusion, ACAM2000 and MVA vaccines are still the best choice for postexposure prevention of monkeypox and smallpox.

Conclusions

In the past 50 years, monkeypox has mainly occurred in the tropical rainforests of central and West Africa. Sporadic cases occur occasionally in countries outside Africa. Bunge et al. pointed out that in the early years (1970–1989), monkeypox was mainly a childhood disease, the median age of onset was four to five years, and 100% of the deaths occurred in children under ten years of age, while for the years 2000 to 2019, children less than ten years of age accounted for 37.5% of the deaths. Moreover, since 2000, the median age of monkeypox cases has increased from ten years in the first decade to 21 years in the second decade [46]. The reason for this age change may be that smallpox was eliminated in 1980. The conventional vaccine is no longer available to the public. It must be emphasized that although the mortality rate of monkeypox infection in children has changed to some extent, it still accounts for a high proportion of deaths. In a recent outbreak, as of August 29, 2022, more than forty-five thousand cases of monkeypox have been reported outside Africa. Genomic analysis results show that the MPXV strain associated with these outbreaks is the WA strain [76]. Early epidemiological reports of the initial cases indicated that the disease occurred mainly in MSM. For the recent monkeypox outbreak, however, the clinical presentation of monkeypox-related cases is mostly atypical and has been variable, and more analysis is still needed to determine the source of the infection. At present, some cases of community transmission, including in women and children, are being reported by some countries. This suggests that monkeypox is also more likely to spread among children. Additionally, MPXV has spread rapidly in a short period of time, causing widespread concern around the world. We can think of three possibilities that explain why MPXV is capable of cross-border spreading: (1) the virus mutates to increase the infectivity of the disease; (2) smallpox vaccination has been stopped; (3) human immunity to MPXV has been reduced, and this has greatly increased the risk of infection; and (4) changes in behavioral patterns of individuals have impacted the spread of the disease.

Despite the progress made in antiviral drugs against smallpox and monkeypox and vaccine development, other public health measures, such as monkeypox monitoring, case investigation and contact tracking, avoiding contact with animals or materials suspected of carrying the disease, using personal protective equipment and maintaining hand hygiene, are still the best measures to prevent and control monkeypox [77, 78]. In addition, the development of monkeypox/smallpox vaccines, monitoring, and MPXV detection technology are critical for the prevention and control of monkeypox. In countries where monkeypox cases are found, the epidemiology and transmission mode should be investigated as much as possible to control the transmission of MPXV in time.

Data availability

This manuscript has no associated data or the data will not be deposited (authors’ comment: this is a theoretical study and no experimental data).

References

Sklenovská N, Van Ranst M. Emergence of monkeypox as the most important orthopoxvirus infection in humans. Front Public Health. 2018;6:241.

Mccollum AM, Damon IK. Human monkeypox. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:260–7.

Durski KN, Mccollum AM, Nakazawa Y, Petersen BW, Reynolds MG, Briand S, et al. Emergence of monkeypox–West and Central Africa, 1970–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:306–10.

Reynolds MG, Doty JB, Mccollum AM, Olson VA, Nakazawa Y. Monkeypox re-emergence in Africa: a call to expand the concept and practice of one health. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2019;17:129–39.

Khodakevich L, Jezek Z, Messinger D. Monkeypox virus: ecology and public health significance. Bull World Health Organ. 1988;66:747–52.

Simpson K, Heymann D, Brown CS, Edmunds WJ, Elsgaard J, Fine P, et al. Human monkeypox–after 40 years, an unintended consequence of smallpox eradication. Vaccine. 2020;38:5077–81.

Rao AK, Schulte J, Chen TH, Hughes CM, Davidson W, Neff JM, et al. Monkeypox in a traveler returning from Nigeria-Dallas, Texas, July 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:509–16.

Yong SEF, Ng OT, Ho ZJM, Mak TM, Marimuthu K, Vasoo S, et al. Imported monkeypox, Singapore. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1826–30.

World Health Organization. Multi-country monkeypox outbreak: situation update. 2022. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2022-DON392. Accessed 10 Jun 2022.

World Health Organization. Monkeypox outbreak: global trends. 2022. https://worldhealthorg.shinyapps.io/mpx_global/. Accessed 29 Aug 2022.

Kozlov M. How does monkeypox spread? What scientists know. Nature. 2022;608:655–6.

Khodakevich L, Szczeniowski M, Nambu-ma-Disu, Jezek Z, Marennikova S, Nakano J, et al. Monkeypox virus in relation to the ecological features surrounding human settlements in Bumba zone Zaire. Trop Geogr Med. 1987;39:56–63.

Damon IK. Status of human monkeypox: clinical disease, epidemiology and research. Vaccine. 2011;29:D54–9.

Petersen BW, Kabamba J, Mccollum AM, Lushima RS, Wemakoy EO, Muyembe Tamfum JJ, et al. Vaccinating against monkeypox in the democratic republic of the congo. Antiviral Res. 2019;162:171–7.

Reed KD, Melski JW, Graham MB, Regnery RL, Sotir MJ, Wegner MV, et al. The detection of monkeypox in humans in the Western Hemisphere. New Engl J Med. 2004;350:342–50.

Marennikova SS, Seluhina EM, Mal’ceva NN, Ladnyj ID. Poxviruses isolated from clinically ill and asymptomatically infected monkeys and a chimpanzee. Bull World Health Organ. 1972;46:613–20.

Beer EM, Rao VB. A systematic review of the epidemiology of human monkeypox outbreaks and implications for outbreak strategy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0007791.

Saijo M, Ami Y, Suzaki Y, Nagata N, Iwata N, Hasegawa H, et al. Virulence and pathophysiology of the Congo Basin and West African strains of monkeypox virus in non-human primates. J Gen Virol. 2009;90:2266–71.

Shchelkunov SN, Totmenin AV, Babkin IV, Safronov PF, Ryazankina OI, Petrov NA, et al. Human monkeypox and smallpox viruses: genomic comparison. FEBS Lett. 2001;509:66–70.

Babkin IV, Babkina IN, Tikunova NV. An update of orthopoxvirus molecular evolution. Viruses. 2022;14:388.

Hughes AL, Irausquin S, Friedman R. The evolutionary biology of poxviruses. Infect Genet Evol. 2010;10:50–9.

Essbauer S, Pfeffer M, Meyer H. Zoonotic poxviruses. Vet Microbiol. 2010;140:229–36.

Nepomnyashchikh TS, Lebedev LR, Ryazankin IA, Pozdnyakov SG, Gileva IP, Shchelkunov SN. Comparison of the interferon γ-binding proteins of the variola and monkeypox viruses. Mol Biol (Mosk). 2005;39:1055–62 (in Russian).

Louten J. Chapter 15-Poxviruses. In: Louten J, editor. Essential human virology. London: Academic Press; 2016. p. 273–90.

Jacobs BL, Langland JO, Kibler KV, Denzler KL, White SD, Holechek SA, et al. Vaccinia virus vaccines: past, present and future. Antiviral Res. 2009;84:1–13.

Zhang Q, Tian M, Feng Y, Zhao K, Xu J, Liu Y, et al. Genomic sequence and virulence of clonal isolates of vaccinia virus Tiantan, the Chinese smallpox vaccine strain. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60557.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC and Texas confirm monkeypox in U.S. traveler. 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2021/s0716-confirm-monkeypox.html. Accessed 16 Jul 2021.

Di Giulio DB, Eckburg PB. Human monkeypox: an emerging zoonosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4:15–25.

Brown K, Leggat PA. Human monkeypox: current state of knowledge and implications for the future. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2016;1:8.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Monkeypox. Signs and symptoms. 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/symptoms.html. Accessed 16 Jul 2021.

Koenig KL, Beÿ CK, Marty AM. Monkeypox 2022 identify-isolate-inform: a 3I tool for frontline clinicians for a zoonosis with escalating human community transmission. One Health. 2022;15:100410.

Mcentire CRS, Song KW, Mcinnis RP, Rhee JY, Young M, Williams E, et al. Neurologic manifestations of the World Health Organization’s list of pandemic and epidemic diseases. Front Neurol. 2021;12:634827.

Huhn GD, Bauer AM, Yorita K, Graham MB, Sejvar J, Likos A, et al. Clinical characteristics of human monkeypox, and risk factors for severe disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1742–51.

Bragazzi NL, Kong JD, Mahroum N, Tsigalou C, Khamisy-Farah R, Converti M, et al. Epidemiological trends and clinical features of the ongoing monkeypox epidemic: a preliminary pooled data analysis and literature review. J Med Virol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.27931.

Petersen E, Kantele A, Koopmans M, Asogun D, Yinka-Ogunleye A, Ihekweazu C, et al. Human monkeypox: epidemiologic and clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and prevention. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019;33:1027–43.

Kabuga AI, El Zowalaty ME. A review of the monkeypox virus and a recent outbreak of skin rash disease in Nigeria. J Med Virol. 2019;91:533–40.

Eltvedt AK, Christiansen M, Poulsen A. A case report of monkeypox in a 4-year-old boy from the DR Congo: challenges of diagnosis and management. Case Rep Pediatr. 2020;2020:8572596.

Ligon BL. Monkeypox: a review of the history and emergence in the Western hemisphere. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2004;15:280–7.

Li D, Wilkins K, Mccollum AM, Osadebe L, Kabamba J, Nguete B, et al. Evaluation of the GeneXpert for human monkeypox diagnosis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;96:405–10.

Li Y, Olson VA, Laue T, Laker MT, Damon IK. Detection of monkeypox virus with real-time PCR assays. J Clin Virol. 2006;36:194–203.

Saxena SK, Ansari S, Maurya VK, Kumar S, Jain A, Paweska JT, et al. Re-emerging human monkeypox: a major public-health debacle. J Med Virol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.27902.

Arita I, Henderson DA. Smallpox and monkeypox in non-human primates. Bull World Health Organ. 1968;39:277–83.

Weinstein RA, Nalca A, Rimoin AW, Bavari S, Whitehouse CA. Reemergence of monkeypox: prevalence, diagnostics, and countermeasures. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1765–71.

Silva NIO, de Oliveira JS, Kroon EG, Trindade GD, Drumond BP. Here, there, and everywhere: the wide host range and geographic distribution of zoonotic orthopoxviruses. Viruses. 2020;13:43.

Ladnyj ID, Ziegler P, Kima E. A human infection caused by monkeypox virus in Basankusu Territory, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Bull World Health Organ. 1972;46:593–7.

Bunge EM, Hoet B, Chen L, Lienert F, Weidenthaler H, Baer LR, et al. The changing epidemiology of human monkeypox—A potential threat? A systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022;16:e0010141.

Li Y, Zhao H, Wilkins K, Hughes C, Damon IK. Real-time PCR assays for the specific detection of monkeypox virus West African and Congo Basin strain DNA. J Virol Methods. 2010;169:223–7.

Chen N, Li G, Liszewski MK, Atkinson JP, Jahrling PB, Feng Z, et al. Virulence differences between monkeypox virus isolates from West Africa and the Congo basin. Virology. 2005;340:46–63.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Update: multistate outbreak of monkeypox–Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Missouri, Ohio, and Wisconsin, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:642–6.

Enserink M. Infectious diseases. U.S. monkeypox outbreak traced to Wisconsin pet dealer. Science. 2003;300:1639.

Bernard SM, Anderson SA. Qualitative assessment of risk for monkeypox associated with domestic trade in certain animal species. United States Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1827–33.

Khodakevich L, Szczeniowski M, Nambu-ma-Disu, Jezek Z, Marennikova S, Nakano J, et al. The role of squirrels in sustaining monkeypox virus transmission. Trop Geogr Med. 1987;39:115–22.

Guarner J, Johnson BJ, Paddock CD, Shieh WJ, Goldsmith CS, Reynolds MG, et al. Monkeypox transmission and pathogenesis in prairie dogs. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:426–31.

Yinka-Ogunleye A, Aruna O, Ogoina D, Aworabhi N, Eteng W, Badaru S, et al. Reemergence of human monkeypox in Nigeria, 2017. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24:1149–51.

Fine PE, Jezek Z, Grab B, Dixon H. The transmission potential of monkeypox virus in human populations. Int J Epidemiol. 1988;17:643–50.

Mauldin MR, Mccollum AM, Nakazawa YJ, Mandra A, Whitehouse ER, Davidson W, et al. Exportation of monkeypox virus from the African continent. J Infect Dis. 2022;225:1367–76.

Nguyen PY, Ajisegiri WS, Costantino V, Chughtai AA, Macintyre CR. Reemergence of human monkeypox and declining population immunity in the context of urbanization, Nigeria, 2017–2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27:1007–14.

Ježek Z, Szczeniowski M, Paluku KM, Mutombo M. Human monkeypox: clinical features of 282 patients. J Infect Dis. 1987;156:293–8.

Adalja A, Inglesby T. A novel international monkeypox outbreak. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175:1175–6.

Hutson CL, Kondas AV, Mauldin MR, Doty JB, Grossi IM, Morgan CN, et al. Pharmacokinetics and efficacy of a potential smallpox therapeutic, brincidofovir, in a lethal monkeypox virus animal model. mSphere. 2021;6:e00927–1020.

Russo AT, Grosenbach DW, Chinsangaram J, Honeychurch KM, Long PG, Lovejoy C, et al. An overview of tecovirimat for smallpox treatment and expanded anti-orthopoxvirus applications. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2021;19:331–44.

Chan-Tack KM, Harrington PR, Choi SY, Myers L, O’rear J, Seo S, et al. Assessing a drug for an eradicated human disease: US Food and Drug Administration review of tecovirimat for the treatment of smallpox. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19:e221–4.

Berhanu A, Prigge JT, Silvera PM, Honeychurch KM, Hruby DE, Grosenbach DW. Treatment with the smallpox antiviral tecovirimat (ST-246) alone or in combination with ACAM2000 vaccination is effective as a postsymptomatic therapy for monkeypox virus infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:4296–300.

Trost LC, Rose ML, Khouri J, Keilholz L, Long J, Godin SJ, et al. The efficacy and pharmacokinetics of brincidofovir for the treatment of lethal rabbitpox virus infection: a model of smallpox disease. Antiviral Res. 2015;117:115–21.

Chan-Tack K, Harrington P, Bensman T, Choi SY, Donaldson E, O’rear J, et al. Benefit risk assessment for brincidofovir for the treatment of smallpox: U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s evaluation. Antiviral Res. 2021;195:105182.

Hoy SM. Tecovirimat: first global approval. Drugs. 2018;78:1377–82.

Delaune D, Iseni F. Drug development against smallpox: present and future. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020;64:e01683–1719.

Grosenbach DW, Honeychurch K, Rose EA, Chinsangaram J, Frimm A, Maiti B, et al. Oral tecovirimat for the treatment of smallpox. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:44–53.

Rizk JG, Lippi G, Henry BM, Forthal DN, Rizk Y. Prevention and treatment of monkeypox. Drugs. 2022;82:957–63.

Adler H, Gould S, Hine P, Snell LB, Wong W, Houlihan CF, et al. Clinical features and management of human monkeypox: a retrospective observational study in the UK. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:1153–62.

Keckler MS, Salzer JS, Patel N, Townsend MB, Nakazawa YJ, Doty JB, et al. IMVAMUNE® and ACAM2000® provide different protection against disease when administered postexposure in an intranasal monkeypox challenge prairie dog model. Vaccines (Basel). 2020;8:396.

Rao AK, Petersen BW, Whitehill F, Razeq JH, Isaacs SN, Merchlinsky MJ, et al. Use of JYNNEOS (smallpox and monkeypox vaccine, live, nonreplicating) for preexposure vaccination of persons at risk for occupational exposure to orthopoxviruses: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:734–42.

Mcneil MM, Cano M, Miller ER, Petersen BW, Engler RJM, Bryant-Genevier MG. Ischemic cardiac events and other adverse events following ACAM2000® smallpox vaccine in the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System. Vaccine. 2014;32:4758–65.

Earl PL, Americo JL, Wyatt LS, Eller LA, Whitbeck JC, Cohen GH, et al. Immunogenicity of a highly attenuated MVA smallpox vaccine and protection against monkeypox. Nature. 2004;428:182–5.

Volkmann A, Williamson AL, Weidenthaler H, Meyer TPH, Robertson JS, Excler JL, et al. The Brighton Collaboration standardized template for collection of key information for risk/benefit assessment of a Modified Vaccinia Ankara (MVA) vaccine platform. Vaccine. 2021;39:3067–80.

World Health Organization. Disease outbreak news. Multi-country monkeypox outbreak in non-endemic countries. 2022. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2022-DON388. Accessed 29 May 2022.

World Health Organization. Multi-country outbreak of monkeypox. External situation report #3–10 August 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/multi-country-outbreak-of-monkeypox--external-situation-report--3---10-august-2022. Accessed 10 Aug 2022.

World Health Organization. Disease outbreak news. Surveillance, case investigation and contact tracing for monkeypox. 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MPX-surveillance-2022.1. Accessed 22 May 2022.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Yuan Qian of Capital Institute of Pediatrics for her advice during the studies and for finalizing the preparation of this paper.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DYM looked up the literatures and wrote the initial draft, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. YH supplemented the materials. THW had critically reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content and analyzed the overall structure of the article. All authors reviewed and agreed the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

No financial or non-financial benefits have been received or will be received from any party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article. The authors have no concflict of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dou, YM., Yuan, H. & Tian, HW. Monkeypox virus: past and present. World J Pediatr 19, 224–230 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-022-00618-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-022-00618-1