Abstract

Background

To identify the prevalence and also the full spectrum of symptoms/complaints of children and adolescents who are suffering from long COVID. Furthermore, we investigated the risk factors of long COVID in children and adolescents.

Methods

All consecutive children and adolescents who were referred to the hospitals anywhere in Fars province, Iran, from 19 February 2020 until 20 November 2020 were included. All patients had a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19. In a phone call to patients/parents, at least 3 months after their discharge from the hospital, we obtained their current status and information if their parents agreed to participate.

Results

In total, 58 children and adolescents fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Twenty-six (44·8%) children/adolescents reported symptoms/complaints of long COVID. These symptoms included fatigue in 12 (21%), shortness of breath in 7 (12%), exercise intolerance in 7 (12%), weakness in 6 (10%), and walking intolerance in 5 (9%) individuals. Older age, muscle pain on admission, and intensive care unit admission were significantly associated with long COVID.

Conclusions

Long COVID is a frequent condition in children and adolescents. The scientific community should investigate and explore the pathophysiology of long COVID to ensure that these patients receive appropriate treatments for their condition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

During the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, people were mainly distressed by its fatality; later on, everybody recognized the psychosocial consequences of this pandemic. More recently, people have noticed the post-acute phase persistent symptoms of the disease [1, 2]. Long COVID has been characterized by symptoms of fatigue, headache, dyspnea, cough, anosmia, etc., and has been more likely to occur in female sex in previous studies of adult populations. In the past couple of months, there have been a dozen publications on this syndrome [3,4,5,6], but little is known about its prevalence and its associated risk factors, specifically in children and adolescents. While there is no globally accepted terminology and definition for this syndrome, persistence of symptoms (e.g., fatigue, breathlessness, cough, joint pain, chest pain, muscle aches, headache, and so on, that could not be attributed to any other cause) beyond 2 weeks for mild disease, beyond 4 weeks for moderate to severe illness, and beyond 6 weeks for critically ill patients have been considered as “long COVID” [7].

In the present study, we aimed to identify the prevalence and also the full spectrum of symptoms/complaints of children and adolescents who are suffering from long COVID. Furthermore, we investigated the risk factors associated with the development of long COVID in children and adolescents who were hospitalized with COVID-19.

Methods

Participants

In Iran, the first confirmed cases of COVID-19 were reported on 19 February 2020 [8]. In this cross-sectional study, children and adolescents (6 to 17 years of age) who were referred to and admitted to hospitals anywhere in Fars province, Iran (population of 4,851,000 people) from 19 February 2020 until 20 November 2020 were included. All patients had a confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis if they were symptomatic and had a positive test result on real-time polymerase chain reaction of nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal samples. The inclusion criteria were as follows: being discharged from hospital (alive), having an available phone number registered in the database, and oral consent by the parent to share the information (see below). We arbitrarily selected the children aged 6 years and older (so they were able to communicate their problems with their parents clearly).

Data collection

For any child or adolescent admitted with COVID-19, the following data were collected at the emergency room by the admitting physician and were entered into a database: age, sex, and symptoms on admission (i.e., fever, cough, respiratory distress, muscle pain, loss of smell, dizziness, headache, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and anorexia). Underlying chronic medical problems also were collected (declared by the parent) [i.e., renal, cardiac, liver, neurological, diabetes mellitus (DM), cancer, hypertension (HTN), pulmonary disorders, etc.]. No data were available about the hospital course of the patients (e.g., laboratory test results).

We randomly selected every other patient in our database (sorted by their phone numbers). If someone did not answer, we selected the previous patient in the list (who was skipped initially). In a phone call to the patients’ care-givers, at least three months after their illness (in March 2021), we inquired about their current health status and obtained their information if the responding parent agreed to participate and to answer the questions (consented orally); in case of adolescents we talked to the patient if their parents allowed us. We specifically asked their symptoms/complaints during the past 7 days to minimize the risk of recall bias.

A data collection questionnaire (Appendix 1) was specifically designed, and all team members were instructed by the first author about how to acquire the data consistently and in a same way. We asked if the patient (parent) had noticed any problems (e.g., muscle or joint pain, weakness, gastro-intestinal symptoms, etc.) during the past week compared with their pre-COVID-19 condition (the arbitrary definition of long COVID in the current study: any symptoms or problems that they did not have before their COVID-19, but have had persistently ever since and during the past 7 days). We also asked the severity of their symptoms/complaints (1) mild and tolerable; 2) moderate; 3) severe and disabling) (subjective and based on the parents’ judgment).

Statistical analyses

Values were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median/ interquartile range (IQR) (based on their normality) for continuous variables and as number (percent) of subjects for categorical variables. Fisher’s exact test, t test (or Mann–Whitney U test), and binary logistic regression analysis model were used for statistical analyses (variables from univariate analyses with a P ≤ 0.1 were entered into the logistic regression analysis model). Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated. A P value (two-sided) less than 0.05 was considered as significant.

Standard protocol approvals

The Shiraz University of Medical Sciences Institutional Review Board approved this study (IR.SUMS.Rec.1399.022). Informed consents to participate in the study have been obtained from participants (or their parent or legal guardian in the case of children under 16 years of age).

Results

General characteristic of the patients

From the start of the pandemic until 20 November 2020, 13,165 patients (all ages) with confirmed COVID-19 were referred to the hospitals in Fars Province; 1694 persons died (case fatality rate: 12.8%) (11,471 were alive). Half of the patients (5735) were contacted, and 427 people (8.4%) of those who were contacted (see the methods) refused to participate in this study, while 518 did not answer the calls. One hundred and nine patients of those who participated in this study (N = 4790) were 17 years of age or younger (2.3%); 58 children and adolescents fulfilled the inclusion criteria (6 to 17 years of age) and were studied. The responders included 56 parents and two adolescents (17 years of age each). The patients included 28 male (48%) and 30 female (52%) individuals. Their mean age was 12.3 years (range: 6-17 years; SD: 3.3 years).

Clinical characteristics of the patients

The most common manifestations of COVID-19 on admission were as follows: fever in 39 (67%), cough in 22 (38%), respiratory distress in 18 (31%), muscle pain in 9 (16%), and diarrhea in 6 (10%) patients. A minority [10 (17.2%)] of the patients needed ICU admission. Duration of the hospital stay was as short as one day to as long as 56 days (mean: 7 days; standard deviation: 9; median: 4; interquartile range: 5). Sixteen patients (27.6%) had pre-existing chronic medical conditions (8.6% malignancy, 6.9% DM, and 6.9% asthma).

Long COVID manifestations

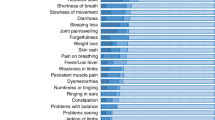

In total, 26 (44.8%) children/adolescents reported symptoms/complaints of long COVID. These symptoms included fatigue in 12 (21%), shortness of breath in seven (12%), exercise intolerance in seven (12%), weakness in six (10%), walking intolerance in five (9%), cough in four (7%), sleep difficulty in three (5%), muscle pain in three (5%), joint pain in three (5%), headache in three (5%), excess sputum in three (5%), and other symptoms (e.g., chest pain, palpitation, loss of smell, sore throat, dizziness, excess sweating, anorexia) in fewer than three individuals. Table 1 shows the severity of the reported symptoms/complaints. While most symptoms/complaints were rated as mild and tolerable by the participants, a minority of them reported severe and disabling problems (e.g., exercise and walking intolerance and sleep difficulty).

Factors associated with long COVID

Table 2 shows factors (at presentation) in association with reporting any long COVID symptoms/complaints in univariate analyses. Long COVID symptoms/complaints were more frequent among older patients, those with muscle pain at the onset of the infection (as a trend), and those who had ICU admission. We included these variables in a regression analysis model. The model that was generated by this test was significant (P = 0.0001). Table 3 shows the results of this analysis. Age, muscle pain on admission, and ICU admission were significantly associated with long COVID in children and adolescents.

Discussion

Thus far, little has been known about the prevalence and the full spectrum of symptoms of long COVID, and its associated risk factors in children and adolescents. In the present study, we observed that more than four in 10 of young patients with COVID-19 (requiring a hospitalization) had long-lasting symptoms/complaints of long COVID. A case series on five children showed that long COVID occurs also in children and that it can be very debilitating [9]. In a study of 384 adult patients (mean age 59.9 years; 62% male) that were followed for a median of 54 days after discharge, 53% reported persistent breathlessness (vs. 12% in our study), 34% had cough (vs. 7% in our study), and 69% reported fatigue (vs. 21% in our study) [10]. In another study of 118 adult patients, at 3-4 months post-COVID, 82% of hospitalized and 64% of non-hospitalized patients had any symptoms (vs. 44.8% in the current study of hospitalized young patients) [5]. It seems that long COVID is much more frequent among adult patients compared with that in children and adolescents. Furthermore, most symptoms/complaints of long COVID in children and adolescents were rated as mild and tolerable by the participants in the current study. Differences in the methodology may explain these different rates of long COVID (we followed the patients for much longer period of time compared with adult studies), but future studies should compare the rates and the severity of long COVID in different age groups of patients. The most common symptoms of long COVID in children and adolescents in our study were fatigue, shortness of breath, exercise intolerance, and weakness. Many of the observed symptoms were consistent with those from previous adult studies [5, 10].

In the present study, we observed that older age, muscle pain on admission, and ICU admission were significantly associated with experiencing long COVID in children and adolescents. In previous adult studies, long COVID was associated with increasing age and female sex [3, 5]. Our observation that ICU admission was significantly associated with experiencing long COVID in children and adolescents and the observation by Sudre et al. [3] that experiencing more than five symptoms during the first week of illness was associated with long COVID in adults may suggest that a more severe COVID-19 at presentation is a significant risk factor for experiencing long COVID during the follow-up. Hypothetically, we can speculate that severe COVID-19 is a risk factor for long COVID because of two possibilities: (1) severe COVID-19 provokes a more severe immune response and cytokine storm, and consequently more organ damage (e.g., lungs, heart, etc.) [11,12,13]; (2) Severe COVID-19 is usually aggressive, is treated invasively with more medications (e.g., antimicrobials, corticosteroids, etc.), and is more frequently associated with iatrogenic harm (e.g., due to intubation or nosocomial infections) with long-lasting consequences. These speculations should be investigated in future studies [14].

Finally, it is noteworthy to mention that the COVID-19 pandemic may profoundly affect young children’s development through loss of time in education, isolation, increase in poverty and food insecurity, loss of caregivers, and heightened stress. These issues can affect not only the entire life course of a child but also the future generations through physiological, psychological, and epigenetic changes occurring in utero and during early stages of development (15).

This study has a limited sample size. In the future research more cases will be used to show the epidemiology of long COVID in Iran. Furthermore, the data on long COVID were not collected prospectively, and we cannot provide any information on the course of long COVID based on the present study. In addition, there might be a problem with information bias because the parents answered the questions on behalf of their children. We did not investigate asymptomatic infections or those with a mild illness in this study. Also, we did not investigate all possible symptoms of long COVID, including changes in the body weight (because it was not feasible in a phone interview and we did not have their premorbid weight). In addition, some of the symptoms we investigated could also be influenced by the psychological stress induced in children (e.g., by isolation). We did not evaluate the psychological issues in this study. Finally, the calculation of the prevalence rate was based on the number of the people who responded to the phone call as the denominator which carries the risk of selection bias.

In conclusion, long COVID is a frequent condition in children and adolescents. This syndrome has significant associations with older age, muscle pain on admission, and ICU admission during the acute phase of the illness.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under licence for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences.

Change history

03 July 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-022-00588-4

References

Walitt B, Bartrum E. A clinical primer for the expected and potential post-COVID-19 syndromes. Pain Rep. 2021;6:e887.

Arnold DT, Hamilton FW, Milne A, Morley AJ, Viner J, Attwood M, et al. Patient outcomes after hospitalisation with COVID-19 and implications for follow-up: results from a prospective UK cohort. Thorax. 2021;76:399–401.

Sudre CH, Murray B, Varsavsky T, Graham MS, Penfold RS, Bowyer RC, et al. Attributes and predictors of long COVID. Nat Med. 2021;27:626–31.

Sykes DL, Holdsworth L, Jawad N, Gunasekera P, Morice AH, Crooks MG. Post-COVID-19 symptom burden: what is long-COVID and how should we manage it? Lung. 2021;199:113–9.

Jacobson KB, Rao M, Bonilla H, Subramanian A, Hack I, Madrigal M, et al. Patients with uncomplicated COVID-19 have long-term persistent symptoms and functional impairment similar to patients with severe COVID-19: a cautionary tale during a global pandemic. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73:e826–9.

Guedj E, Campion JY, Dudouet P, Kaphan E, Bregeon F, Tissot-Dupont H, et al. (18)F-FDG brain PET hypometabolism in patients with long COVID. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48:2823–33.

Raveendran AV. Long COVID-19: challenges in the diagnosis and proposed diagnostic criteria. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2021;15:145–6.

https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/iran/. Accessed 14 Mar 2021.

Ludvigsson JF. Case report and systematic review suggest that children may experience similar long-term effects to adults after clinical COVID-19. Acta Paediatr. 2021;110:914–21.

Mandal S, Barnett J, Brill SE, Brown JS, Denneny EK, Hare SS, et al. “Long-COVID”: a cross-sectional study of persisting symptoms, biomarker and imaging abnormalities following hospitalisation for COVID-19. Thorax. 2021;76:396–8.

Batabyal R, Freishtat N, Hill E, Rehman M, Freishtat R, Koutroulis I. Metabolic dysfunction and immunometabolism in COVID-19 pathophysiology and therapeutics. Int J Obes (Lond). 2021;45:1163–9.

Mehra B, Aggarwal V, Kumar P, Kundal M, Gupta D, Kumar A, et al. COVID-19-associated severe multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children with encephalopathy and neuropathy in an adolescent girl with the successful outcome: an unusual presentation. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2020;24:1276–8.

García-Salido A, de Carlos Vicente JC, Belda Hofheinz S, Balcells Ramírez J, Slöcker Barrio M, Leóz Gordillo I, et al. Severe manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 in children and adolescents: from COVID-19 pneumonia to multisystem inflammatory syndrome: a multicentre study in pediatric intensive care units in Spain. Crit Care. 2020;24:666.

Sterky E, Olsson-Åkefeldt S, Hertting O, Herlenius E, Alfven T, Ryd Rinder M, et al. Persistent symptoms in Swedish children after hospitalisation due to COVID-19. Acta Paediatr. 2021;110:2578–80.

Yoshikawa H, Wuermli AJ, Britto PR, Dreyer B, Leckman JF, Lye SJ, et al. Effects of the Global Coronavirus Disease-2019 pandemic on early childhood development: short- and long-term risks and mitigating program and policy actions. J Pediatr. 2020;223:188–93.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AAA-P: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, software, supervision, validation, visualization, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing. HN, MS, AA, AE, ML, MR, ZB, MK, ZZ, MF-K, AJ, FS, SA, MN, and SN: data curation, investigation, methodology, project administration, validation, visualization, and writing—review and editing. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

The Shiraz University of Medical Sciences Institutional Review Board approved this study (IR.SUMS.Rec.1399.022).

Conflict of interest

Ali A. Asadi-Pooya: Honoraria from Cobel Daruo, RaymandRad and Tekaje; Royalty: Oxford University Press (Book publication). Other authors declared no conflict of interest.

Informed consent

Informed consent to participate in the study has been obtained from participants (or their parent or legal guardian in the case of children under 16 years of age).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Asadi-Pooya, A.A., Nemati, H., Shahisavandi, M. et al. Long COVID in children and adolescents. World J Pediatr 17, 495–499 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-021-00457-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-021-00457-6