Abstract

East Kazakhstan is physiographically a diverse region of north-central Asia encompassing a broad array of geomorphic zones and geo-ecosystems from the western open steppes to the interior arid basins with wind-sculptured surfaces of the surrounding rocky highlands aligned by the high alpine mountain ranges. The complex regional geological history gave rise to a mosaic of impressive landforms located within a relatively small area. The extraordinary relief with many unique geo-sites was generated by dynamic processes associated with the late Cainozoic orogenesis in conjunction with the past climatic variations. The cyclicity of bedrock weathering and mass sediment transfer are manifested by Mesozoic fossiliferous formations, large sand dune fields, and loess-palaeosol-cryogenic series providing archives of the Quaternary evolution. Pleistocene glaciations followed by cataclysmic floods from the released ice-dammed lakes during the recessional glacier stages have produced an exceptional imprint in the mountain areas. Many archaeological localities and historic monuments, some being a part of the UNESCO World Natural and Cultural Heritage, are associated with the most prominent topographic places. Geo-tourism focusing on the most exquisite landscapes and spectacular geological settings is the new trend in the country with still minor activities that take advantage of the region’s supreme geoheritage potential. The great geo-diversity accentuates the touristic value of this still marginally explored geographic area. Reconnaissance, documentation, and publicity of the most unique geo-sites and geo-parks provide an impetus for their registration in the national and international nature heritage protection programs under proper geo-environmental conservation policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Contrary to overall awareness of cultural heritage, national conceptions of geoheritage aimed at the preservation of unique landscape forms and geological formations are still a relatively new trend (Brocx and Semeniuk 2007; Brocx 2008; Gray 2008; Robinson and Percival 2011; van der Ancker 2012; Reynard 2012; Ruban 2015; de Wever et al. 2015; Fauzi and Misni 2016; Hose 2016; Crofts 2018; Gordon et al. 2018, etc.). Especially in the developing countries, this may play a major role in the international tourism advancement and the sustainable socio-economic growth (e.g. Leman et al. 2008; El Wartiti et al. 2008; Asrat et al. 2012; Ehsan et al. 2013; Kiernan 2013; Henriques and Neto 2015; Kiernan 2015; Nazaruddin 2017; Czerniawska and Chlachula 2018). The associated and globally emerging geo-tourism as a form of tourism focusing on the most interesting geographic loci, relief features, and geological formations contributes to public consciousness, to a greater appreciation of the national geoheritage value, and to regional development and economic growth (Goessling and Hall 2005; Dowling and Newsome 2010; Dowling 2009, 2011).

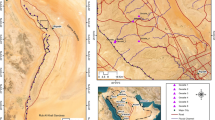

The Republic of Kazakhstan, situated in the north of Central Asia (2,724,900 km2) inspires a lot of attention due to its spectacular landforms many of which are world-unique. Yet, there still has been a marginal activity promoting the country’s geoheritage potential (Saparov and Zhensikbayeva 2016; Zhensikbayeva et al. 2018). East Kazakhstan/Восточно-казахстанская область (283,000 km2), administratively a part of the Tomsk Gubernia of former Imperial Russia until the 1930s, belongs naturally to the most picturesque and physiographically diverse countries. Located at its easternmost limits, the territory integrates the specific physiographic, climatic, and biotic elements of the southern Siberian, Mongolian, and Central Asian bio-geographic units that emphasize the region’s distinctiveness and exceptionality (Fig. 1).

Physiography of East Kazakhstan with the location of the principal and most attractive geoheritage and geo-tourism areas and geo-sites discussed in the text: (1) West Altai Nature Reserve, (2) Katon-Karagay State National Park (KKNP), (3) Lake Markakol Nature Reserve, (4) Zaisan Basin, (5) Kalba Range, (6) Tarbagatai Range, and (7) Central Kazakhstan Highlands. Geoheritage sites: (1) Shingistau Highlands, (2) Lakes Sibinskiye, (3) eastern Central Kazakhstan Highlands, (4) Arshaty (Southern Altai Range), (5) Uryl’-Zhambul, (6) Chindagatui, (7) Berel’, (8) West Altai Nature Reserve, (9) Kiin-Kerish badlands, (10) Aygyrkum sand fields, (11) Izkutty, (12) Ak-Bauyr, (13) Shilikty, (14) “Austrian Road,” (15) Tarchanka, (16) Glubokoye, (17) Lake Tainty, and (18) Akkurum (Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6)

Although still rather insufficiently investigated because of the present Kazakh-Russian-Chinese border zone, this geographic area shows a complex Quaternary history—2.59 million years ago to the present (Cohen et al. 2013)—and the associated (palaeo)-environmental transformations reflected by dynamic geomorphic processes related to the past global climate evolution in conjunction with the regional orogenic (tectonic) activity (Deviatkin 1965; Buslov et al. 2004; Dyachkov et al. 2014). Marked climatic shifts are evidenced by well-preserved palaeo-landscape sites in the mountain, steppe, and semi-desert regions, as well as by sedimentary geology, palaeoecology, and geoarchaeology records indicating long-term variations in temperature and humidity. Stratified and high-resolution loess-palaeosol sections from the western and northern Altai foothills incorporating multi-proxy environmental and geoarchaeology data of the Pleistocene-age ecology provide evidence of a rather pronounced natural dynamics for the last 130,000 years (Chlachula 2003; Bábek et al. 2011). Except for the most appealing geomorphic locations, the East Kazakhstan region is well known for numerous cultural monuments with the most ancient dating back to the Early and Middle Palaeolithic (Chlachula 2010). The systematic field reconnaissance, documentation, and publicity of these places provide a background for the inclusion of these localities in the natural and cultural patrimonies of the country, some under the protection of the UNESCO. This study discusses the existing geoheritage of East Kazakhstan by presenting examples of the most distinctive physiographic features that add to the exquisite cultural history of this most attractive region. In unity, both the natural and the cultural landscape elements form a promising context for the modern geo-tourism development integrated in the framework of the traditional Kazakh environmentally oriented occupation milieu.

Geo-Environments of the Study Area

The study area is located at the easternmost limits of the Republic of Kazakhstan bordering in the north the Omsk and Altai regions of SW Siberia, Russia, and in the east the Xing-Jang Province (NW China) (Fig. 1). The district of East Kazakhstan (with the administrative centre Ust’-Kamenogorsk/Oeskemen) belongs to the historically developed parts of the country due to rich natural resources (including decorative stones and precious minerals) industrially processed since the seventeenth century (Sherba et al. 2000; Chernenko and Chlachula 2017; Chlachula 2020). The present climate is strongly continental (MAT − 5/− 3°C) with warm summers and very cold dry winters and rather pronounced seasonal temperature variations (Yegorina 2015). The uneven annual (rainfall and snow) precipitation, ranging from 150 mm in the aridest eastern semi-deserts of the Zaisan Lake basin to > 1500 mm on the NW flanks of Rudno Altai together with the great regional relief diversity, pre-determines the marked vegetation zonality. Mixed and dark coniferous taigas are the principal biotopes in the mid- and high-elevation mountains, whereas arid rocky steppes transgressing in the west into open grasslands characterize the lowlands. The main regional hydrology network belongs to the Irtysh drainage system with the Black Irtysh and Bukhtarma rivers being the main tributaries. Perennial streams seasonally water the semi-deserts.

East Kazakhstan is characterized by the most varied physiography of a > 4000 m elevation gradient. The main geomorphic units (Fig. 2) are represented by high mountain ranges enclosing the territory. A chain of the east-west-oriented massifs—the Rudno Altai Mountains (1000–2200 m asl), the Khozun Range (2565 m), the Listviaga Range (2877 m), and the Katun’ Range (4503 m)—aligns the region from the north; the Narym Range (2533 m), the Sarymsakty (3373 m), the Southern Altai (3871 m), and the Kurchum (2645 m) Ranges from the east, connecting through the Tarbagatai Range (2992 m); and the Saur massive (3816 m) and the Dzhundarskiy Alatau (4464 m) in the south to the Tian-Shan Mountains (Schultz 1948; Mikhailov 1961). The Kazakh Altai is the principal mountain system bordering the Mongolian Altai through the Tabon-Bogdo-Ula massive (Nairamdal Mt., 4356 m). The central part of East Kazakhstan is structured by low-elevation hills of the Kalba Mountains (1606 m) of the Central Kazakh Highlands adjoining in the east the Zaisan tectonic depression filled by lakes—the Zaisan and the Bukhtarma Basins (300–400 m asl) amidst a dry xerotheric landscape (Nekhoroshev 1967; Deviatkin 1981; Akhmetyev et al. 2005).

Landforms and geo-sites of East Kazakhstan. a, b Pyramidal rocky hills of the exposed and horizontally disintegrated regional granite bedrock forming outstanding landscape structures amid the open fescue-/feather-grass steppe land (Shingistau Highland, 700 m asl). c, d Unique Palaeozoic formations of a decompression-onion-layered and wind-abraded volcanic bedrock intercalated by metamorphosed gneiss and schist at Lakes Sibinskiye—a popular touristic site in the Kalba Range (700–1698 m asl.). e A scenic countryside of the East-Central Kazakhstan Highlands (Mel’kosopochnik) with a bizarre and most diverse geo-relief of rocky hills and canyon valleys enclosing numerous settlement sites and linguistically bound to prehistoric and historical nomadic ethnics occupying this vast area of the ancient Sary-Arka. f Strongly wind-corroded Cambrian granites with pocket-shaped surface cavities sculptured by aeolian coarse quartz crystals abrasion. Photographs by the author

The region exhibits a complex geological and physiographic development with a broken relief configuration of undulating parklands, adjoining the western steppes, and the surrounding mountains (Figs. 1 and 3a). The geomorphology of East Kazakhstan is very dynamic due to the continental plate tectonics acting along the main orogenic chain of central Eurasia (Schulz 1948; Nekhoroshev 1958; Svarichevskaya 1965; Veselova 1970). The pre-Cainozoic landscape history of this continental area of Central Asia is characterized by a low topographic gradient of the old planation surfaces and the former palaeo-sea basins subsequently dissected by the late Miocene Earth crust movement (Chupakhin 1968; Yegorina 2002). The broader regional geology is structured by the Proterozoic igneous and metamorphic rocks (Fig. 2) mantled by the Palaeozoic, Devonian, Carboniferous, and Palaeogene formations of volcanogenic and sedimentary (sandstone and limestone) origins filling the interior syncline depressions (the Bukhtarma and Zaisan Basins). The lack of vegetation and the intensive erosional processes disclose the rocky Pre-Cambrian and loose Mesozoic bedrock exposed to the present surface as remnant pediments (Fig. 4c) or buried by unconsolidated Cainozoic deposits (Fig. 4d) amassed in the intra-continental sedimentary basins (Aubekerov 1993; Dodonov 2002; Mikhailova 2002). The intensive erosion of the uplifted geological formations led to several denudation cycles flattening the former relief (Obruchev 1951). The central steppe area is built by foliated granites in places interspersed by gneiss units that form rounded hills and up to 100 m-elevated flat platforms. The 400–1500-m elevations are distorted by long-term weathering processes and sculptured into the exposed rocky tops free of vegetation. The igneous and metamorphic geological bodies of the Altai mountain system host rich metallic and non-metallic mineral resources including varieties of (semi-)precious gemstones known and exploited since prehistory (Pacekov et al. 1990; Gusev 2007, 2020). Karstic cavities are developed in the Palaeozoic limestone (Mikhailov 1961). Lower-gradient palaeogeography characterizes the open steppe settings.

Landforms and geo-sites of East Kazakhstan. a The Southern Altai Range (3487 m asl) with a high-gradient alpine relief sculptured by orogenesis, cyclic glaciations, and active post-glacial geomorphic processes. b The Last Glacial kar (cirque) at the northern slope of the Tarbagatai/Southern Altai Range (2995 m asl) and the Katon-Karagay State Nature Park, with a well-preserved moraine in the bottom part created by the Little Ice Age (fifteenth to nineteenth century) mountain ice advance. c A sequence of prominent platform-like glacio-fluvial terraces formed at the end of the Last Ice (Uryl’, Katon-Karagay District). d Granite boulders on top of a glacio-fluvial terrace providing evidence of an extreme high-energy hydraulic palaeo-setting. e Vertical granitic rocks shaped by glacial erosion and frost actions (Zhambul, Katon-Karagay District). f “A Rocky Fairy Tale”—weathered wind-eroded Proterozoic granite bedrock formations (the West Altai Nature Reserve, Zyryansk District). Photographs by the author

Landforms and geo-sites of East Kazakhstan. a Wind-sculptured unconsolidated glacial deposit (till) remnants (Akkurum, Chulyshman Valley, Teleckoye Lake area, and Gorno Altai). b A series of erosional terraces in the upper reaches of the Bukhtarma valley (Chindagatui, KKNP) providing evidence of the final Last Ice Age climate change. c Stratified Mesozoic sedimentary geological series of the Kiin-Kerish (“difficult pass”) badlands (~300 ha) in the Zaisan Basin semi-desert (Kurchum District) incorporating rich Jurassic fossil fauna remains. d Pre-Quaternary iron-mineral coloured clayey formations indicative of past hot and humid tropical climates. e The Aygyrkum sand field (~40 × 15 km) with up to 300 m-high dunes resulting from a long-term aeolian accumulation of a drifting sand from the interior Zaisan Basin and creating a spectacular natural barrier along the present Kazakh-Chinese border. f Loess-palaeosol section at Izkutty on the western slopes of the Kalba Range with the most continuous climate-stratigraphic sequence of the Late Pleistocene and Holocene climate evolution (the last 130,000 years) in the southern Altai area. Photographs by the author

In addition to the regional orogeny, the Cainozoic climate change was the main agent modelling the modern relief (Baibatsha and Aubekerov 2003). Pronounced long-term atmospheric variations are indicated by the preserved palaeo-landscape forms in the high mountain as well as in steppe settings yielding the most spectacular geo-sites. These are manifested by the large-scale glacial and sedimentary geology sections and the associated geomorphology structures indicating marked and sequenced past climate shifts triggering mass erosional and accumulation process and geomorphic dynamics. The topography of the alpine ranges (> 3000 m asl) (Fig. 3a, b) documents the cyclic Quaternary glaciations accompanied by intensive fluvial and cryogenic mass slope flows active in mountain valleys, with the best-preserved landforms dating to the Last Glacial Stage (74,000–12,000 years ago/yr BP) (Galakhov and Mukhametov 1999). Spectacular glacio-fluvial terraces in the inter-montane basins indicate periodic releases of ice-dammed glacial lakes subjected to cataclysmic drainages during the final stages of the alpine-zone deglaciation, being the most dramatic geomorphic processes in the latest geological history (Fig. 3c) (Butvilovskiy 1985; Rudoy and Baker 1993; Baker et al. 1993; Rudoy and Kirianova 1994; Herget 2005; Agatova et al. 2020). The strongly continental cold and hyper-arid climate generated permafrost formation in the ice-free foothills with periodic surface-cover gravity denudations during warmer stages.

Apart from glaciations, the regional Quaternary (< 2.59 Ma) landscape evolution is best evidenced by strongly weathered massive ferruginous palaeosols formed during the warmest (early) Pleistocene interglacials and the previous warm Cainozoic periods (Fig. 4d).The onset of Late Pleistocene (130,000–12,000 yr BP) brought a more pronounced continentality contributing to a progressing geo-relief gradient. Extensive aeolian (wind-blown) sands and silt formations (Fig. 4e) mantle the smoothened foothill topography with the preserved palaeo-landforms. The stratified loess-palaeosol sedimentary profiles in conjunction with the inter-bedded palaeoecology and geoarchaeology palaeoclimate proxy records point to the long-term variations in the regional air temperature and aridity/humidity balance (Fig. 4f) (Chlachula 2010; Bábek et al. 2011). The Holocene (< 11,700 yr BP) warming led to the establishment of the present-day ecosystems.

Three specific bio-geographic provinces attain the territory of East Kazakhstan—the central Kazakhstan province (between the Aral Sea and West Siberia), the southern Siberian (Yenisei) province, and the Central Asian (the Tian-Shan—Mongolian Altai) province (Velikovskaya 1946; Grigoriev 1950; Chupakhin 1968). The distinct geomorphological diversity in conjunction with the strongly continental climate regime gave rise to a variety of pristine biotopes of the alpine tundra, mountain taiga, foothill parklands, lowland steppes, and semi-deserts hosting unique flora and fauna (Chlachula 2007). The current aridification, best evidenced in the continental basins by an active sand dune formation and mass aeolian sediment transfer, contributes to the arid-steppe ecosystem instability and the neo-relief formation. Overall, the study area displays an immense geomorphic variety of landforms, geo-sites, and the associated natural habitats.

Geo-Site Classification

Natural Geo-Sites

The present topography of East Kazakhstan mirrors the complex geological development of the region. The acting past orogenic and tectonic geomorphic processes are well evident in the regionally/locally specific landforms shaping the original geological formations. In terms of the most prominent and typical natural geo-sites, this is best manifested by the prominent rocky exposures of the uplifted volcanic and interspersed metamorphic bedrock forms sculptured by aeolian erosion and long-term thermal stress (freezing and heating through solar radiation) over the past thousands to millions of years (Fig. 2). The resulting scenic landscapes with barren, horizontally or onion-layered, flat-top pyramidal and rounded rocky hills are the most distinctive relief features of the open East Kazakhstan forest-free highlands (Fig. 2a–d). The low-relief landscapes formed by unconsolidated deposits are best preserved in the interior Zaisan and Bukhtarma basins defined by the peneplanation topography of the ancient continental depressions (Fig. 4c, d). The exposed massive stratified and structurally variegated sedimentary units produced the most attractive geological and palaeontological (dinosaur-fauna-bearing) locations (Fig. 4c) alongside unique and chronologically continuous fossiliferous formations sealing the evidence of the Mesozoic life of major scientific relevance (Fig. 6c, d). Especially the fossil palaeontological occurrences rich in East Kazakhstan deserve most attention for research, geo-tourism promotion, and geo-education (Page 2018).

The climate cycles of the Pleistocene Epoch shaped the neo-tectonically rising topography of the alpine mountain ranges separated by deep river valleys filled by ice-water bodies during the periodic ice advances leaving behind the most impressive glacigenic landforms, such as water- and wind-eroded glacial till remnants (Fig. 4a), sequenced recessional glacio-fluvial terraces (Fig. 4b), and other prominent geo-forms. The palaeoclimate dynamics are observed from the aeolian formations along the Altai foothills analogous to the best European loess-palaeosol geo-sites (Antoine et al. 2013) (Fig. 4f). The climate-driven regional relief restructuring continues until today giving a rise to new and most interesting geo-settings.

Cultural Geo-Sites

The present East Kazakhstan Region was occupied by people since the ancient times as witnessed by various prehistoric and early historical cultures and traditions that allow for the interpretations of the past lifestyles and natural adaptations (Baumer 2016a, b). The archaeological sites are often contextually associated with some of the most attractive relief forms and geographic locations leaving a testimony of once-flourishing settlements (Fig. 5). Rocky overhangs, abris, and structural cavities were used as sites for diverse functions (occupation, ritual, and raw-material processing) (Fig. 5b). In spite of the very close ties of the Kazakh people to nature, predetermined by the principal pastoral economies in the vast Central Asian steppes, occasionally very little appreciation is paid to these cultural geo-sites that are often damaged or even destroyed (e.g. modern graffiti drawn over the original prehistoric zoomorphic rock engravings). Even at the regional administration level, awareness of the national geo-diversity value is still rather minor with the absence of legal regulatory status of the pristine geo-sites’ protection.

Cultural-heritage geo-sites of East Kazakhstan. a A Stone Age locality at the margin of the former glacial lake with discarded stone tools and humanly modified granite boulders providing evidence of a Final Pleistocene human occupation of the deglaciated Bukhtarma valley (Zhambul, Katon-Karagay District). b Rock-drawings at the prehistoric (Neolithic to Bronze Age) cultic place Ak-Bauyr made on granite rock face overhangs. c, d The famous “royal” cemetery in the “Royal/Golden Valley” at Berel’ (Katon-Karagay District) with the early Iron Age burial mound complex of the Pazyryk culture (6th–second C. BC); d Excavation of a kurgan grave (Fig. 5c) incorporating a mummified human body with offerings preserved in permafrost grounds (2006). e An early medieval (ca. fifth century AD) sacral monument of a circular structure made of dry-bricks at Shilikty (Zaisan District) documenting an ancient tribal settlement in the middle of the Zaisan desert. f A historical cemetery linked with the initial pastoral Kazakh settlements of the Southern Altai (Chindagatui). Photographs by the author

Industrial Geo-Sites

In addition to the natural and cultural geo-sites, modern anthropogenically/industrially generated sites have created a prominent imprint to the countryside modifying the original landscape. This reflects the fact that East Kazakhstan was the key region of strategic resource exploitation and processing of the Kazakh SSR (the Soviet Union). These places relate to infrastructure development, such as road cuts, quarries, water-retention channels deepened into the bedrock, or industrial hills of metallic processing (smelting) wastes among other examples (Fig. 6a, c, e, f). Even in the mountain regions, the pristine natural sceneries are supplemented by distinctive anthropogenic geo-relief construction elements, such as the “Austrian Road” built during the First World War (in 1914–1916) by the imprisoned Austrian soldiers who fought against the Tsarist Russian army (Fig. 6b). These and other anthropogenic relief elements constitute a part of modern history.

Modern anthropogenic geo-sites of East Kazakhstan. a A geological structure of the regional metamorphic bedrock (gneiss) exposed by road construction (100 km east of Ust’-Kamenogorsk). b The “Austrian Road” built in 1915–1916 across the Sarym-Sakty Range at 1500–2200 m asl connecting the Bukhtarma Valley (N) with the Black Irtysh Basin (S); c A key historical geology site at Tarchanka (Glubokoye District) with the complete Upper Devonian-Lower Carboniferous sequence exposed by limestone extraction at the Ul’ba River. d Tarchanka section (since 1976 a nature monument)—a fossil plant imprint from the time of a shallow Mesozoic Altai Sea (330–360 Ma ago). e An industrial hill of a cooper smelting residual waste and basalt-ore processing of the former (USSR) metallurgic factory at Glubokoye (since 2005 revitalized as the Irtysh Cooper-Smelting Enterprise). f An artificial canyon cutting a fossiliferous limestone at Lake Tainty (1040 m asl, 1100 × 400 m, 54 km SE of Ust’-Kamenogorsk) fed by spring water and representing a supreme regional geo-site. Photographs by the author

Past Landscapes and Peoples

The broad array of the East Kazakhstan landscapes completed by the numerous cultural monuments of diverse ages provides a testimony of human occupancy of the steppe and foothill habitats since the earliest stages of human prehistory (Chlachula 2018). The affluent cultural heritage and the varied geo-sites found amid of pristine nature in addition to rich customs of the traditional Kazakh pastoral communities jointly underline the high attractiveness of the region for geo- and ecotourism (Yegorina et al. 2016; Zhensikbayeva et al. 2018). The past regional physio-geography, climates, and environmental conditions predetermined the sequenced prehistoric and historical settlements of the broader area. The cultural sites are regularly associated with the most picturesque settings and the prominent relief forms indicating a natural harmony and a close liaison of the ancient peoples and the countryside.

The mapped archaeological localities in East Kazakhstan and the neighbouring Gorno Altai are unearthed from miscellaneous geo-contexts (fluvial, aeolian, and cryogenic among others). The associated Quaternary geology and palaeoecology records from the investigated archaeological sites provide evidence of marked environmental dynamics. The Palaeolithic sites, associated with tectonically uplifted bedrock platforms or accumulative fluvial terraces and, at later stages, isolated rocky promontories with game hunting-oriented strategic positions (Fig. 5a), represent altogether the earliest cultural geo-sites occupied by the pre-modern (pre-sapiens) humans (Chlachula 2001, 2010). Plentiful stone tools of various technical and typological oblique discarded at the places of proper lithic raw material occurrences (bedrock outcrops) attest to a very early (Pleistocene-age) inhabitation of this geographically marginal Central Asian territory. The Altai mountain valleys and the foothills delivered cave sites and shelters providing evidence to specific adaptations of the Last Ice-Age hunting-gathering populations.

The later (post-glacial) inhabitation encompasses a wide range of geo-sites. The prehistoric rock art, rich burial complexes, ancient ritual sites, and refugia hidden in the protected mountain valleys and the river-cut canyons eloquently report on the Holocene-age Neolithic and Aeneolithic pastoral ethnics (Fig. 5b). The most fascinating cultural records, however, are associated with the Bronze Age (late fourth–early first millennium BC) and especially the early historical times (sixth century BC–ninth century AD). The latter are represented by the Iron Age “royal” stone burial mounds (kurgans) (Fig. 5c, d), isolated ceremonial structures, and rock-engraved petroglyphs found on in the mountain river valleys and on the high plateaus and assigned to the Scythian Period (sixh–second centuries BC), leaving behind the most famous cultural relics registered in the UNESCO World Heritage in Eastern Kazakhstan as well as the neighbouring Russian Gorno Altai (Akishev 1978; Polosmak 2001; Samashev 2001, 2011; Gorbunov et al. 2005).

The geographic distribution of the mapped archaeological sites/cultural geo-sites chronologically encompassing the antiquity and the late historical times (Fig. 5e, f) displays a broad topographic range of the formerly occupied landscapes embracing the regional altitudinal zones from ~400 m asl in the lower reaches of the river valleys up to ~2500/3000 m asl on the high mountain plateaus (such as Plateau Ukok) (Bykova and Bykov 2014; Chlachula 2018). Except for the natural settings, the places/outcrops of local gemstones known since the ancient times enhanced the settlement and ancient exploration attractiveness of present East Kazakhstan. Precious and semi-precious stones were exploited and traded along the northern part of the Silk Road that followed through the study area since prehistory as testified by finds of gemstone jewels from the Bronze Age, Iron Age, and the early historical archaeological sites (Chlachula 2020). Overall, the dual unity of the cultural and natural heritage of East Kazakhstan in the frame of the Altai-Sayan Eco-Region is of major relevance for geo-tourism promotion and geo-site conservation (Sukhova and Garms 2014).

Human Occupation Geography—Toponymy Background

Except for the cultural archives in the form of the prehistoric and historical localities and settlement features imprinted into the countryside, the non-material culture records provide additional multi-proxy information on the land history. The long temporal occupancy of East Kazakhstan (referred to in the ancient epics as Sary-Arka) by different tribes and population groups is evidenced by place names reporting on the particular geographic areas and the specific topographic sites (Saparov et al. 2018). According to present archaeology and ethnology evidence, Sary-Arka has actual geomorphic foundations and a direct linkage to the relief mosaics of the undulating hilly rocky steppes and parklands (Fig. 1). The etymology of the main physiographic entities provides a tool for reconstructing and learning about the history of ethnics that occupied this broad and unusually varied territory. This knowledge is an integral part of the Kazakh geoheritage and has an unquestionable national cultural-historical significance.

The linguistic data completing the material culture records show a rather complex and chronologically long cultural-historical development best reflected by the names of the major East Kazakhstan rivers and mountains (hydronyms and oronyms) (Konkashpayev 1959; Kenesbayev et al. 1971). Yet, not all the principal geo-site names can be confidently determined by using modern onomastics. A local uniformity of some toponyms across this extensive area indicates a common cultural background and certain past ethnic homogeneity and/or mobility of the ancient populations inhabiting these physiographically diverse lands. Linkage with the most prominent strategic topographic settings is well evident since the earliest times pointing to the adaptation to the local mountain and steppe environments (e.g. Levine and Kislenko 1997; Vishnyatsky 1999). Whereas the hydronyms of the Sary-Arka may have an intricate and not a fully clear origin with a connection to the ancient tribes and nations, the principal oronyms (Altai, Tarbagatai, Alatau, Shingistau, Bayanaul etc.) clearly show their Mongolian provenance. The later medieval Turkic-Tatar occupation is eventually mirrored by the present Kazakh language forms including those of numerous geo-sites.

The place names deliver direct insights into the past population shifts in northern Central Asia throughout the millennia since the most ancient Indo-European inhabitation through the Bronze and Iron Ages (third and first millenia. BC) until the historical period (second millenium AD) represented by nomadic and territorially mobile to semi-sedentary tribes. A major cultural-geographic imprint was left behind by the Mongolian invasion into parkland-steppes of the present northern Kazakhstan during the thirteenth century (Baumer 2016c) and the following Turkic-Tatar clans politically integrated into hordes and representing the multi-ethnic substratum of the modern Kazakh nation. The local uniformity of some toponyms across the extensive area, assuming a common cultural background during the particular temporal stages, attests to a certain ethnic homogeneity and/or mobility of the ancient populations inhabiting this vast and geomorphically mosaic land. This suggests a close relationship and interactions (including demographic exchanges and mixing) between the past pastoral ethnics in the parkland-steppe and semi-desert areas north of Lake Balkhash between the Aral Sea and the southern Urals in the west and the Alatau–Altai Mountain systems in the east.

Understanding the landscape names thus has major relevance for the regional cultural geography (Crang 2013) taking into account the relief and the associated geo-ecosystem and settlement peculiarities of the Sary-Arka/East Kazakhstan territory. Finally, the new knowledge also adds to a closer cultural geo-site categorisation and the contextual geological phenomena interpretations.

Geoheritage Conservation Risks and Priorities

In terms of the regional geoheritage conservation and public promotion (Brocx 2008), Kazakhstan is still at the initial stage by having a general lack of awareness and appreciation of the existing geo-relief and its cultural-historical value and meaning. Complex field mapping and proper documentation should be carried out and not be limited just to the geo-sites listed by UNESCO such as the Plateau Ukok or the central Bukhtarma “Golden Valley” (Molodin et al. 2004; Samashev 2011). Other prominent and regionally specific geo-relief sites should be adequately treated by underlining their uniqueness. Interdisciplinary Quaternary (geological, geomorphologic, and pedological) investigations represent a constituent part of the Eastern Kazakhstan geo-diversity studies in terms of the acting past natural processes, their dynamics, and chronology, allowing for the reconstruction of the regional physiographic history and the present relief formation. The distinct Last Ice Age mountain topography attests to the intensity of these processes and pronounced climatic fluctuations since the Last Glacial. A progressing retreat of the mountain glaciers reinforced by global warming observed across the broader Altai (Surazakov et al. 2007; Chlachula and Sukhova 2011; Narozhniy and Zemtsov 2011; Shangedanova, et al. 2010) exposes new landforms in the recently deglaciated alpine zone. Particularly, the most spectacular structural elements of glacial landscapes represent a major asset to the local geoheritage programme (Kiernan 1996) (Fig. 3b, c).

As mentioned above, many ancient cultural places (such as the prehistoric rock art sites (Fig. 5b), canyons hiding early ritual sites, opulent burial complexes, and decorated stone stelae among other monuments) often relate to the naturally most unique and prominent landscape forms and places and represent a contextual geoheritage component (Asrat and Zwolinski 2012). The discovered archaeological localities bound to the diverse geo-settings bear witness to repeated colonisation and settlements of this land and specific forms of adaptation to the local (palaeo-)environments (Aubekerov 1993; Chlachula 2018). The earliest Stone Age occupation localities, found on the present wind-deflated surfaces or buried in the stratified alluvial and thick aeolian formations, endow the initial peopling antiquity of the country (Chlachula 2010). Except for the most famous locations (such as the royal Scythian cemeteries of the “Golden Valley”) (Samashev 2014) (Fig. 5c, d), the cultural sites are still being treated with certain negligence and even disrespect, and their national geo- and cultural heritage positive reception and a spiritual meaning are undervalued and underestimated. Although well known among the locals, the consciousness of their cultural-historical significance is rather low, and some monuments are being wilfully damaged. Underlining the linkage and meaning (both scientific and public) between the geo-sites and the sacred cultural places is of primary importance.

Apart from the human factors, the present regional climate-related geo-environmental shifts generate risks to the geoheritage of East Kazakhstan. This particularly concerns the current status of preservation/rescue of permafrost-sealed and most authentic cultural localities (Hahn 2006; Cheremisin 2006; Jakobson-Tepfer 2008). Geo-archaeological reconnaissance and regular monitoring are prerequisites for the preservation and/or the rescue of these unique cultural geo-sites. Systematic fieldwork contributes not only to improved knowledge of the regional geoheritage, but also to the protection of the natural/cultural monuments with the corresponding legal actions which are the key priorities. The visibility, identification, and selection of the prime geo-sites are the basics for the geo-contextual and geographic evaluation of the geoheritage resources (Mikhailenko and Ruban 2019). The structural landscape mapping and a GIS visualisation constitute a background for the spatial distribution assessment of the specific geo-sites (Hovorková and Chlachula 2012; Brilha 2016) with regard to their proper conservation needs. Ultimately, the newly mapped localities have a major bearing for not only scientific research, but also the regional environmental management of the nature-protected areas hosting the most unique landscape elements and for the national geo-/eco-tourism promotion. The selected principal geo-sites are assessed by their uniqueness among other relief places, by their spatial pattern (occurrence, visibility, density, concentrations, diversity, and complexity) and their physical preservation with respect to other geo-relief features. Legislative regulations are recommended to mitigate destruction of these unique natural places and geoarchaeological locations due to local industrial activities (infrastructure development, mining, building construction, etc.). As a methodological framework, appropriate multi-disciplinary geo-, bio-, and social science approaches should be implemented for the geo-site categorisation system taking into account the extraordinary geomorphic diversity of East Kazakhstan (Zhensikbayeva et al. 2017). A systemised geoheritage management is beneficial to visitors and local operators.

In summary, the specific physiographic attributes of the patterned landscape features found across East Kazakhstan comply with the international geoheritage criteria (e.g. Wimbledon and Smith-Meyer 2012). These relief forms are nationally, some globally, significant as they pertain to the exclusive geological and geomorphological places and the contextually associated cultural sites that jointly offer insights into the regionally unique evolution of the Earth. However, they also provide novel scientific knowledge, public information, and teaching references. Finally, the most exceptional geo-sites found amid the great geological sceneries meet the standards of the global geo-park networks (Komoo and Patzak 2008) and offer new geo-tourism destinations.

Geo-Tourism of East Kazakhstan

Eastern Kazakhstan is one of the most colourful and authentic regions of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Many nationalities (~30) reside on its territory, mainly Kazakh (60%) and Russian (36%) largely mixed in urban places. The ethnically pure Kazakh settlements are mostly rural centred in the eastern areas. In respect to the progressing industrial development initiated in the seventeenth century, the region has major potential for geo-/eco-tourism and geography recreation adding to the long-term socio-economic rise of the country. The overwhelmingly domestic visitors’ travel increasingly contributes to the settlement sustainability of the mountain and especially the most environmentally vulnerable arid (semi-)desert zone as an alternative to the traditional pastoral economy on which the majority of the locals depends. The foreign tourism to these areas, largely undiscovered by abroad visitors, is still sporadic in the range of a few hundreds visiting the most popular places such as the Katon-Karagay National Park and Lake Markakol Nature Reserve (Fig. 1) per year.

East Kazakhstan has the best geo-tourism predispositions in view of the natural beauty and the most attractive and pristine landscapes. The major Altai-Tarbagatai mountain systems, constituting the extreme NE frontiers of the republic along with the adjoining Gorno Altai and the Chinese Altai, offer the best tourism and recreation opportunities (Dunets 2011; Harms et al. 2016; Sukhova et al. 2016; Kabdrakhmanova et al. 2019; Song 2010; Wang et al. 2014a, b) that can well compete with other mountain regions in the world (e.g. Newsome and Dowling 2010; Ilieş et al. 2017; Melinte-Dobrinescu et al. 2017; Bouzekraoui et al. 2018); the same is true about the semi-desert places. The present relief and the existing socio-cultural milieu underline the specific uniqueness of these places for exploration, adventure, and leisure-time geo-tourism activities (Chikhachev 1974; Yerdavletov 2000; Swarbrooke et al. 2003; Geta et al. 2015). These are accentuated by the region’s location in the border zone adjoining the other (Russian, Mongolian, and Chinese) nature protection reserves and the national parks integrated into the broader physiographic entity of the “Great Altai” listed in the World Natural and Cultural Heritage sites of UNESCO. The past and present environmental conditions associated with the particular geomorphic settings and the continental atmospheric regime gave rise to the variety of (palaeo-)ecosystems hosting rich endemic and rare biota with distinctive floral and faunal communities reflecting the extreme geographic and bio-climatic zonality of the territory (Kozhamkulova and Kostenko 1984; Chlachula 2007, 2011; DNK World News 2017).

The multi-facetted cultural evolution exemplified by the numerous prehistoric and historical sites provides testimony of a balanced natural adjustment of people to the extreme continental environments of Inner Asia (Gorbunov and Gorbunova 1994; Baybatsha 1998; Agatova et al. 2016). The more recent settlements have locally altered the former geo-relief by large-scale construction activities (Zaisan and Bukhtarma Lakes), intensified agrarian practices, or mineral mining. A differential anthropogenic impact is particularly evident in the previously pristine places due to the expanding agriculture and pastoralism surmounting the natural capacity during Soviet times. Most of the original countryside, however, remained preserved in terms of relief and biota. The integration of the geo-ecosystems, natural habitats, and cultural landscapes on the sparsely populated territory offers the best conditions for eco-tourism, mainly in the biotically precious (but most vulnerable) desert and alpine mountain areas.

All these locations have a major potential not just for fundamental scientific research, but primarily for the geoheritage promotion, geo-education, and the regional geo-tourism and recreation geography programme inauguration (Kuskov 2005; Mazbaev 2016; Dunets et al. 2019). The existing concepts of the present geoheritage documentation and conservation, as well as the geo-tourism management efforts centred in the major nature protection sites, such as the Katon-Karagay State Nature Park (Chlachula 2007), meet well the world standards (e.g. Brocx 2008; Wimbledon and Smith-Meyer 2012). The social and environmental impact of the visitors’ travel, including various geo-tourism and rural tourism activities, should be taken into account in their planning by the local administrations and regional governments (Inskeep 1994; Jenner and Smith 1992; Mihalič 2000; Mason 2015; Saarinen et al. 2017). This primarily concerns the most visited natural park and protected nature reserve locations.

The study of climate variations affecting the relief structure and the associated semi-desert, parkland-steppe, and alpine-zone geo- and biodiversity is essential for understanding the current geo-environmental transformations over the territory. This also adds to the geo-tourism concept as a part of the national economic progress. Yet, because of the limited logistics and the border-zone entry regulations, especially for the most scenic and least developed eastern areas of East Kazakhstan (Fig. 1), many of these locations remain unexposed to modern geo-/eco-tourism because of the limited accessibility. The local implementation of geo-tourism may partly substitute for the narrow rural work market and slow down the present depopulation trends due to high unemployment or natural stress. The latter is well exemplified by the progressing desert land expansion along the Chinese (Xing-Jiang) border and the degradation/aridisation of agricultural lands, which represents a highly negative factor in respect to environmental sustainability and the settlement stability of this southeastern part of East Kazakhstan.

Conclusion

The great geo-diversity of the scenic and multifarious East Kazakhstan landscapes reflects the broad variety of geomorphic processes—endogene and exogene—acting on the territory over the past millions of years. Some of the most attractive relief forms and geographic locations enclose the preserved archaeological sites and historical monuments providing witness of an ancient occupancy of the region.

The duality of the regional geoheritage and cultural heritage, embraced into the traditional framework of the landscapes’ and peoples’ interactions, offers an expressive insight into the geological history and human adaptations to the local natural settings and ecosystems. The distinctive aesthetic and physio-geographic features together with the rich cultural sites provide a most favourable geo-contextual milieu for modern geo-tourism by taking into account the regionally specific natural, historical, cultural, and socio-economic aspects. Some of the most geomorphically diverse places are globally unique.

In spite of this, awareness of the country’s extraordinary geoheritage and geo-tourism potential is still rather low at the state’s administration and the public level. Overall, the geoheritage issue in Kazakhstan is in a developing stage. In the northeastern part of the country, this is further impeded by the limited field accessibility due to the poor infrastructure and the restricting Kazakh-Russian-Chinese border zone entry regime. The complex geo-sites’ field mapping, scientific evaluation and categorisation, geo-contextual analyses, and definition of the embracing statutory processes with the implementation of the corresponding legal actions for the most exceptional and authentic landscape forms/geo-sites protection are a priori the central prerequisites for formal geoheritage recognition and conservation. Conversely, the close cultural-historical relationship of the traditional Kazakh people lifestyles can, in a natural way, add to the installation of a vital geo-tourism in this marginal geographic area contributing to its local sustainable development.

References

Agatova AR, Nepop RK, Bronnikova MA, Slyusarenko IY, Orlova LA (2016) Human occupation of South Eastern Altai highlands (Russia) in the context of environmental changes. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 8:419–440

Agatova AR, Nepop RK, Carling PA, Bohorquez P, Khazin LB, Zhdanova AN, Moska P (2020) Last ice-dammed lake in the Kuray basin, Russian Altai: New results from multidisciplinary research. Earth-Sci Rev (in press) 205:103183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2020.103183

Akhmetyev MA, Dodonov AE, Sotnikova MV (2005) Kazakhstan and Central Asia (plains and foothills). In Velichko AA, Nechaev VP (Eds) Cenozoic Climatic and Environmental Changes in Russia. Geological Society of America, pp.139–161

Akishev KA (1978) Kurgan Issyk. Art of the Saks of Kazakhstan. Nauka, Moskva, 131p. (in Russian)

Antoine P, Rousseau DD, Degeai JP, Moine O, Lagroix F, Kreutzer S, Juchs M, Hatté C, Gauthier C, Svoboda J, Lisá L (2013) High-resolution record of the environmental response to climatic variations during the Last Interglacial - Glacial cycle in Central Europe: The loess-palaeosol sequence at Dolní Věstonice (Czech Republic). Quat Sci Rev 67:17–38

Asrat A, Zwolinski Z (2012) Geoheritage: from geoarchaeology to geotourism. Editorial Quaestiones Geographicae 31(1):5–6

Asrat A, Demissie M, Mogessie A (2012) Geoheritage conservation in Ethiopia: The case of the Simien Mountains. Quaestiones Geographicae 31(1):7–23

Aubekerov BZh (1993) Stratigraphy and paleogeography of the plain zones of Kazakhstan during the Late Pleistocene and Holocene. Development of landscape and climate in northern Asia in Late Pleistocene and Holocene 1:101–110. Nauka, Moskva (in Russian)

Bábek O, Chlachula J, Grygar J (2011) Non-magnetic indicators of pedogenesis related to loess magnetic enhancement and depletion from two contrasting loess-paleosol sections of Czech Republic and Central Siberia during the last glacial-interglacial cycle. Quat Sci Rev 30:967–979

Baibatsha AB, Aubekerov BJ (2003) Quaternary geology of Kazakhstan. Niz Flym, Almaty (in Russian)

Baker VC, Benito G, Rudoy AN (1993) Paleohydrology of Late Pleistocene superflooding, Altai Mountains, Siberia. Nature 259:348–350

Baumer C (2016a) The history of Central Asia. Vol. 1: The Age of the Steppe Warriors. I.B. Tauris Press, 372p

Baumer C (2016b) The history of Central Asia. Vol. 2: The Age of the Silk Roads. I.B. Tauris Press, 288p

Baumer C (2016c) The history of Central Asia. Vol.3: The Age of Islam and the Mongols. I.B. Tauris Press, 408p

Baybatsha A (1998) The ancient history of the Kazakh steppe. Sanat Press, Almaty, 46p (in Russian)

Bouzekraoui H, Barakat A, Elyoussi M, Touhami F, Mouaddine A, Hafid A, Zwoliński Z (2018) Mapping geosites as gateways to the geotourism management in Central High-Atlas (Morocco). Quaestiones Geographicae 37(1):87–102

Brilha J (2016) Inventory and quantitative assessment of geosites and geodiversity sites: A review. Geoheritage 8(2):119–134

Brocx M (2008) Geoheritage: From global perspectives to local principles for conservation and planning. Western Australian Museum, Welshpool, Western Australia

Brocx M, Semeniuk V (2007) Geoheritage and geoconservation - History, definition, scope and scale. J R Soc West Aust 90:53–87

Buslov MM, Watanabe T, Fujiwara Y, Iwata K, Smirnova LV, Safonova IY, Semakov NN, Kiryanova AP (2004) Late Paleozoic faults of the Altai region, Central Asia: Tectonic pattern and model of formation. J Asian Earth Sci 23(5):655–671

Butvilovskiy VV (1985) Catastrophic releases of waters of glacial lakes of the South-Eastern Altai and their traces in relief. Geomorphology 1985(1):65–74 (in Russian)

Bykova VA, Bykov NI (2014) Natural conditions of southeastern Altai and their role in the life in the Pazyryk period society. Barnaul University Press, Barnaul, 186p. (in Russian)

Cheremisin DV (2006) Frozen tombs in the Altai Mountains: Strategies and perspectives. Archaeol Ethnol Anthropol Eurasia 27(1):157–159

Chernenko ZI, Chlachula J (2017) Precious and decorative non-metallic minerals from East Kazakhstan: Geological deposits and present utilisation. Proceedings, 17th International Multidisciplinary Scientific Geoconference SGEM, Sofia, 29.06.-05.07.2017. Vol. 17, Issue 11: Science and Technologies in Geology Exploration and Mining, STEF92 Technology Press, Sofia, pp. 447–454

Chikhachev PA (1974) Travel in East Kazakhstan. Nauka, Moskva, 317p (in Russian)

Chlachula J (2001) Pleistocene climates, natural environments and palaeolithic occupation of the Altai area, west Central Siberia. In Prokopenko S, Catto N, Chlachula J (Eds.) Lake Baikal and surrounding regions.), Quat Int 80-81:131–167

Chlachula J (2003) The Siberian loess record and its significance for reconstruction of the Pleistocene climate change in north-Central Asia. In: Dust indicators and Records of Terrestrial and Marine Palaeoenvironments (DIRTMAP) (E. Derbyshire, editor). Quat Sci Rev 22 (18–19):1879–1906

Chlachula J (2007) Biodiversity protection of southern Altai in the context of contemporary environmental transformations and sustainable development. Sector 2–3 (East Kazakhstan). Final report field studies 2007, Irbis, Staré Město, 152p

Chlachula J (2010) Pleistocene climate change, natural environments and Palaeolithic peopling of East Kazakhstan, in Chlachula J, Catto N, (Eds.) Eurasian perspectives of environmental archaeology. Quat Int 220:64–87

Chlachula J (2011) Biodiversity and environmental protection of southern Altai. Studii Sicomunicari Stiintelenaturii 27(1):171–178

Chlachula J (2018) Environmental context and adaptations of the prehistoric and early historical occupation of the southern Altai (SW Siberia – East Kazakhstan). Archaeol Anthropol Sci 11(5):2215–2236

Chlachula J (2020) Gemstones of East Kazakhstan. Geologos 22(2):125–148 (in press). https://doi.org/10.2478/logos-2020-0013

Chlachula J, Sukhova MG (2011) Regional manifestations of present climate change in the Altai, Siberia. In: Xuan L (ed) Proceedings, the ICEEA 2nd international conference on environmental engineering and applications, Shanghai, China (august 19–21, 2011). Environmental engineering and applications, vol 17. IACSIT Press, Singapore, pp 134–139

Chupakhin V (1968) Physical Geography of Kazakhstan. Alma-Ata. “Mektep” Press, 260p. (in Russian)

Cohen KM, Finney SK, Gibbard PL, Fan J-X (2013) The ICS international chronostratigraphic chart. Episodes 36(3):199–204

Crang M (2013) Cultural geography. Routledge Press, New York and London, 205p

Crofts R (2018) Putting geoheritage conservation on all agendas. Geoheritage 10(2):231–238

Czerniawska J, Chlachula J (2018) The field trip in the Thar Desert. Landform Analysis 35:21–26

de Wever P, Alterio I, Egoroff G, Cornee A, Bobrowsky P, Collin G, Durranthon F, Hill W, Lalanne A, Page KN (2015) Geoheritage, a national inventory in France. Geoheritage 7:205–247

Deviatkin EV (1965) Cenozoic deposits and neotectonics of the South-Eastern Altai Proceedings of the GIN AN SSSR Volume 126, 244p. (in Russian)

Deviatkin EV (1981) The Cainozoic of the inner Asia. Nauka, Moskva, 196p

DNK World News (2017) Unique open-air paleontological museum at Tarchanka: an East Kazakhstan State University Project, Ust-Kamenogorsk, 2018–2019. https://dknews.kz/lifestyle/132-culture/35340-v-vko-budet-sozdan-unikalnyj-paleontologicheskij-muzej-pod-otkrytym-nebom-imeyushchij-drevnejshie-skalnye-okamenelosti.html

Dodonov AE (2002) Quaternary of Central Asia: Stratigraphy, correlation, Palaeo-geography. GEOS, Moskva, 250p. (In Russian)

Dowling RK (2009) Geotourism’s contribution to local and regional development. In: de Carvalho C, Rodrigues J (eds) Geotourism and local development. Camar municipal de Idanha-a-Nova, Portugal, pp 15–37

Dowling RK (2011) Geotourism’s global growth. Geoheritage 3(1):1–13

Dowling RK, Newsome D (2010) Global geotourism perspectives. Goodfellow Publishers, Woodeaton, Oxford

Dunets AN (2011) Tourist and recreational complexes of mountain region, Altai State University Press, Barnaul, 150p

Dunets AN, Zhogova IG, Sycheva IN (2019) Common characteristics in the organization of tourist space within mountainous regions: Altai-Sayan region (Russia). GeoJ Tour Geosites 24(1):161–174

Dyachkov BA, Mayorova NP, Chernenko ZI (2014) History of East Kazakhstan geological structures development in the Hercynian, Cimmerian and Alpine cycles of tectonic genesis, Part ІІ. Proceedings of the Ust-Kamenogorsk Kazakh Geographical Society, D. Serikbaev East Kazakhstan State Technical University Press, Ust-Kamenogorsk, pp. 42–48 (in Russian)

Ehsan S, Leman MS, Begum RA (2013) Geotourism: A tool for sustainable development of Geoheritage resources. Adv Mater Res 622–623(2013):1711–1715

El Wartiti M, Malaki A, Zahraoui M, El Ghannouchi A, Gregorio FD (2008) Geosites inventory of the northeastern Tabular Middle Atlas of Morocco. Environ Geol 55(2):415–422

Fauzi MS, Misni A (2016) Geoheritage conservation: Indicators affecting the condition and sustainability of Geopark – A conceptual review. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 222:676–684

Galakhov VP, Mukhametov PM (1999) Glaciers of the Altai. Nauka, Novosibirsk, 136p

Geta RI, Yegorina AV, Saparov KT, Zhensikbaeva NZ (2015) Methods for assessing the recreational potential of the Kazakhstan part of Altai on the basis of information theory. Acad Nat Sci Int J Exp Educ (Moscow) 2015:10–14

Goessling S, Hall CM (2005) Tourism and global environmental change. Ecological, social, economic and political interrelationship. Routledge Publishers, London–New York, 331p

Gorbunov A, Gorbunova I (1994) Burial mound permafrost of the Altai. Permafr Periglac Process 5(4):289–292

Gorbunov A, Samashev Z, Severskiy E (2005) Treasures of frozen kurgans of the Kazakh Altai. Materials of the Berel’ Burial Ground. Il’-Tech-Kitap, 114p

Gordon JE, Crofts R, Díaz-Martínez E (2018) Geoheritage conservation and environmental policies: retrospect and Prospect. In: Reynard E, Brilha J (eds) Geoheritage. Elsevier, Chennai, pp 213–236

Gray M (2008) Geoheritage 1: Geodiversity: A new paradigm for valuing and conserving geoheritage. Geosci Can 35(2):51–59

Grigoriev VV (Ed.) (1950) Kazakhstan, general physiogeographic characteristics. Nauka, Leningrad, 492p (in Russian)

Gusev AI (2007) The Altay geoheritage and gemology with the basis of the gemmo-tourism. Biysk State University Press, 187p (in Russian)

Gusev AI (2020) Gemology of Altai and Salair. Pedagogical State University of Biysk, 320p. (in Russian)

Hahn J (2006) Impact of the climate change on the frozen tombs in the Altai Mountains. Heritage at Risk 2006(2007):215–217

Harms E, Sukhova M, Kocheeva N (2016) On the concept of sustainable recreational use of natural resources of cross-border areas of Altai. J Environ Manag Tour 2(14/7):158–164

Henriques MH, Neto K (2015) Geoheritage at the Ecuador: selected geo-sites of São Tomé Island (Cameron Line, Central Africa). Sustainability 7(1):648–667

Herget J (2005) Reconstruction of Pleistocene ice-dammed lake outburst floods in Altai Mountains, Siberia. Geological Society of America, Special Publication, 386p

Hose TA (Ed.) (2016) Geoheritage and geotourism: A European perspective. The heritage matters series, volume 19, Boydell Press, Newcastle University, Woodbridge, 336p

Hovorková M, Chlachula J (2012) Methods and visualisation of geographic information system in the southern Altai. News of the Department of the National Geographic Society in the Altai Republic, University of Gorno Altai, Gorno Altaisk, 2012(3):42–48

Ilieş M, Ilieş G, Hotea M, Wendt JA (2017) Geomorphic attributes involved in sustainable ecosystem management scenario for the Ignis-Gutai Mountains Romania. J Environ Biol 38(5):1121–1127

Inskeep E (1994) National and regional tourism planning: Methodologies and case studies. Rutledge, New York, 249p

Jakobson-Tepfer E (2008) Culture and landscape of the high Altai. In: Preservation of the Frozen Tombs in the Altai Mountains, UNESCO, pp. 31–34

Jenner P, Smith C (1992) The tourism industry and the environment. Special Report: Economist Intelligence Unit, no. 2354, 355p

Kabdrakhmanova N, Mussabayeva M, Atasoy E, Zhensikbayeva N, Kumarbekuly S (2019) Landscape and recreational analysis of Yertis river upper part on the basis of basin approach (Kazakhstan). GeoJ Tour Geosites XII(4/27):1392–1400

Kenesbayev SK, Abdrakhmanov AA, Donidze GI (1971) Place names of Kazakhstan, their research, writing and transcription. Proceedings of the Academy of Sciences of the KazSSR. Public Series 4:73–74

Kiernan K (1996) Conserving Geodiversity and Geoheritage: The conservation of glacial landforms, Australian Heritage Commission, Hobart, 244p

Kiernan K (2013) The nature conservation, geotourism and poverty reduction nexus in developing countries: A case study from the Lao PDR. Geoheritage 5(4):207–225

Kiernan K (2015) Landforms as sacred places: Implications for geodiversity and geoheritage 7(2):177–193

Komoo I, Patzak M (2008) Global geoparks network: An integrated approach for heritage conservation and sustainable use. In: Leman MS, Reedman A, Pei CS (Eds). Geoheritage of east and southeast Asia. Lestari Universiti Kibangsaan, Ampang Press, Kuala Lumpur, pp. 3–13

Konkashpayev GK (1959) Kazakh folk geographical terms. Proceedings of the Academy of Sciences of the KazSSR. Geographical Series 3, p.7. (in Russian)

Kozhamkulova AA, Kostenko NN (1984) Extinct animals of Kazakhstan. (Palaeogeography of the late Cainozoic). Nauka, Alma-Ata, 104 p. (in Russian)

Kuskov AS (2005) Recreation geography: Methodical complex, Moscow, 496p

Leman MS, Reedman A, Pei CS (Eds) (2008) Geoheritage of east and southeast Asia. Lestari Universiti Kibangsaan, Ampang Press, Kuala Lumpur, 308p

Levine M, Kislenko A (1997) New Eneolithic and Early Bronze Age radiocarbon dates for North Kazakhstan and South Siberia. Camb Archaeol J 7(2):297–300

Mason P (2015) Tourism impacts, planning and management. Routledge, Oxon, UK. 253p

Mazbaev OB (2016) Geographical bases of territorial development of tourism in Republic of Kazakhstan, Ph.D. Thesis, Al-Farabi Kazakh National University, Аlmaty, 138p (in Russian)

Melinte-Dobrinescu MC, Brustur T, Jipa D, Macaleţ R, Ion G, Ion E, Popa A, Stănescu I, Briceag A (2017) The geological and palaeontological heritage of the Buzău Land Geopark (Carpathians, Romania). Geoheritage 2017(9):225–236

Mihalič T (2000) Environmental management of a tourism destination: A factor of tourism competitiveness. Tour Manag 21(1):65–78

Mikhailenko AV, Ruban DA (2019) Geo-heritage specific visibility as an important parameter in geo-tourism resource evaluation. Geosciences 9:146. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences9040146

Mikhailov NI (1961) Mountains of southern Siberia. Nauka, Moskva (in Russian)

Mikhailova NI (2002) Environmental evolution of East Kazakhstan in Cainozoic period. In: Regional Components in System of Ecological Education, Ust-Kamenogorsk, pp. 88–93 (in Russian)

Molodin VI, Polosmak NV, Novikov AV, Bogdanov ES, Slyusarenko IYu, Sheremisin DV (2004) Archaeological monuments of the Plateau Ukok (Gorno Altai). IAET SB RAS, Novosibirsk, 255p. (in Russian)

Narozhniy Y, Zemtsov V (2011) Current state of the Altai glaciers (Russia) and trends over the period of instrumental observations 1952–2008. AMBIO 40:575–588

Nazaruddin DA (2017) Systematic studies of geoheritage in Jeli District, Kelantan, Malaysia. Geoheritage 9(1):19–33

Nekhoroshev VP (1958) Geology of the Altai. Moskva, Gosgeoltekhizdat, 262p (in Russian)

Nekhoroshev VP (1967) Eastern Kazakhstan. Geological structure, In: Sidorenko AV, Nedra M (Eds.), Geology of the USSR, Volume 41, Nauka, Moskva–Leningrad, 467p. (in Russian)

Newsome D, Dowling RK (eds) (2010) Geotourism: The tourism of geology and landscape. Goodfellow Publishers, Woodeaton

Obruchev VA (1951) Selected works on geography of Asia. Volume 2, Geografizdat, Moskva, 400 p. (in Russian)

Pacekov UM, Jukova AA, Alekseyev AG, Artemeva EL (1990) Minerals of Kazakhstan, IGS AS KazSSR, Alma Ata, 196p. (in Russian)

Page KN (2018) Fossils, heritage and conservation: Managing demands on a precious resource. In: Reynard E, Brilha J (eds) Geoheritage. Elsevier, Chennai, pp 107–128

Polosmak NV (2001) Inhabitants of Ukok. Infolio, Novosibirsk, pp. 334 (in Russian)

Reynard E (2012) Geoheritage protection and promotion in Switzerland. Eur Geol 2012(34):44–47

Robinson AM, Percival IG (2011) Geotourism, geodiversity and geoheritage in Australia – Current challenges and future opportunities. Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales 132, pp. 1–4

Ruban DA (2015) Geoheritage in Europa and its conservation. J Environ Policy Plan 17(1):151–153

Rudoy AN, Baker VR (1993) Sedimentary effects of cataclysmic late Pleistocene glacial outburst flooding, Altay Mountains, Siberia. Sediment Geol 85:53–62

Rudoy AN, Kirianova MR (1994) Lacustrine and glacial lake formation and Quaternary palaeogeography of the Altai. Proc Russian Geogr Soc 121(3):236–244 (in Russian)

Saarinen J, Rogerson CM, Hall CM (2017) Geographies of tourism development and planning. Tour Geogr 19(3):307–317

Samashev Z (2001) Archaeological monuments of the Kazakh Altai. Institute of Archaeology, Almaty, 108p (in Russian)

Samashev Z (2011) Berel’. Ministry of Education and Science, Archaeological Institute, Taimas Press, Astana, 236p

Samashev Z (2014) Tsar Valley. Archaeological Institute, Astana, 236p. (in Kazakh)

Saparov КТ, Zhensikbayeva NZ (2016) Evaluation of the natural resource potential of the southern Altai. Vestnik, D. Serikbayev East Kazakhstan state Technical University. Sci J (Ust-Kamenogorsk) 2016:66–71

Saparov K, Chlachula J, Yeginbayeva A (2018) Toponymy of the ancient Sary-Arka (north-eastern Kazakhstan). Quaestiones Geographicae 37(3):37–54

Schulz SS (1948) Analysis of Neotectonics and relief of the Tian-Shan. Proceedings of the Soviet Geographical Society, Vol. 1, Nauka, Moskva-Leningrad, 201p. (in Russian)

Sherba GN, Bespayev ХА, Dyachkov BА (2000) Large Altai (geology and metallogeny). RIO VAC RK, Almaty, 400p. (in Russian)

Song H (2010) The geological heritages in Xinjiang, China: Its features and protection. J Geogr Sci 20:357–374

Sukhova MG, Garms EO (2014) Bioclimatic conditions of Russian Altai landscapes as a factor of sustainable tourism development. World Appl Sci J 30:187–189

Sukhova MG, Harms EO, Babin VG, Zhuravleva OV, Karanin AV (2016) Functional zoning as an instrument for sustainable development of tourism of Great Altai. Int J Environ Sci Educ 11(15):7506–7514

Surazakov AB, Aizen VB, Aizen EM, Nikotin SA (2007) Glacier changes in the Siberian Altai Mountains, the Ob river basin, (1952–2006) estimated with high resolution imager. Environ Res Lett 2(4):1–7

Svarichevskaya I (1965) Geomorphology of Kazakhstan and Central Asia. Nauka, Leningrad (in Russian)

Swarbrooke J, Beard C, Leckie S, Pomfret G (2003) Adventure tourism, the new frontier, in: Oxford, Butterworth-Heineman, 354p

van der Ancker H (2012) Geodiversity and geoheritage, modern perspectives for earth scientists and for Europe. Eur Geol 2012(34):6–7

Velikovskaya EM (1946) Relief development of the southern Altai and Kalba and deep gold placers. Bull Moscow Inst Petrol Geol Section 21(6):57–77 (in Russian)

Veselova LK (1970) Morphostructure of the south-eastern Kazakhstan Mountains. In: Geography of Desertic and mountain region of Kazakhstan, Nauka, Moskva-Leningrad, pp. 38–48 (in Russian)

Vishnyatsky LB (1999) The paleolithic of Central Asia. J World Prehist 13(1):69–122

Wang Z, Yang Z, Wall G, Xua X, Hana F, Dua X, Liua W (2014a) Is it better for a tourist destination to be a world heritage site? Visitors’ perspectives on the inscription of kanas on the world heritage list in China. J Nat Conserv 23:19–26

Wang F, Zhang X, Yang Z, Luan F, Xiong H, Wang Z, Shi H (2014b) Analysis on spatial distribution characteristics and geographical factors of Chinese National Geoparks. Central Eur J Geosci 6(3):279–292

Wimbledon WAP, Smith-Meyer S (Eds.) (2012) Geoheritage in Europe and its conservation. Oslo, ProGEO, 405p. ISBN 978-82-426-2476-5

Yegorina АV (2002) Physical geography of East Kazakhstan, Ust-Kamenogorsk, EHI Press, 181p. (in Russian)

Yegorina АV (2015) The climate of Southwest Altai, Textbook, Semey, 315p (in Russian)

Yegorina А, Saparov КТ, Zhensikbayeva N (2016) The structure of the geo-cultural space of Southern Altai as a factor of tourist-recreational development. Vestnik, КNU, Scientific Journal. Almaty, pp. 214–219

Yerdavletov SR (2000) Geography of tourism: history, theory, methods. Practice Textbooks, Аlmaty, 336p. (in Russian)

Zhensikbayeva N, Saparov K, Atasoy E, Kulzhanova S, Wendt J (2017) Determination of Southern Altai geography propitiousness extent for tourism development. GeoJ Tour Geosites 9(2):158–164

Zhensikbayeva NZ, Saparov KT, Chlachula J, Yegorina AV, Atasoy A, Wendt JA (2018) Natural potential of tourism development in southern Altai. GeoJ Tour Geosites IX/1(21):200–212

Acknowledgements

The geography and geoheritage investigations in East Kazakhstan were a part of field studies coordinated by the author and supported by the Czech Ministry of Environment, the IRBIS NGO, and the East Kazakhstan State University, Ust’-Kamenogorsk. Dr. E. Little (Geological Survey of Canada, Calgary) provided contributing comments on the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chlachula, J. Geoheritage of East Kazakhstan. Geoheritage 12, 91 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12371-020-00514-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12371-020-00514-y