Abstract

Schizophrenia is characterized by positive, negative, cognitive, and affective symptoms. Antipsychotic medications, which work by blocking the dopamine D2 receptor, are the foundation of pharmacotherapy for schizophrenia to control positive symptoms. Cariprazine is a dopamine D3 receptor-preferring D3/D2 partial agonist antipsychotic that is approved for the treatment of schizophrenia (USA and European Union [EU]) and manic and depressive episodes associated with bipolar I disorder (USA). Partial agonist agents have a lower intrinsic activity at receptors than full agonists, so they act as either functional agonists or functional antagonists depending on the surrounding neurotransmitter environment. Beyond efficacy against positive symptoms, the unique D3-preferring partial agonist pharmacology of cariprazine suggests potential advantages against negative symptoms, and cognitive and functional impairment, which are challenging to treat. The efficacy and safety of cariprazine in adult patients with schizophrenia have been demonstrated in four short-term randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials, two long-term open-label studies, one relapse prevention study, and one prospective negative symptom study versus the active comparator risperidone. Additional post hoc investigations have supported efficacy across individual symptoms and domains in schizophrenia, as well as in diverse areas of interest including cognition, functioning, negative symptoms, hostility, and global well-being. This comprehensive review of cariprazine summarizes its pharmacologic profile, clinical trial evidence, and post hoc investigations. Collective evidence suggests that the pharmacology of cariprazine may offer broad-spectrum efficacy advantages for patients with schizophrenia, including effects against difficult-to-treat negative and cognitive symptoms, as well as functional improvements. Cariprazine was generally safe and well tolerated in patients with short- and long-term exposure and no new safety concerns were associated with longer-duration treatment.

Trial registration ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers, NCT00404573, NCT00694707, NCT01104766, NCT01104779, NCT01412060, NCT00839852, NCT01104792.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

This article presents an overview of the pharmacology and clinical trial evidence of cariprazine in the treatment of adult patients with schizophrenia. |

Cariprazine is a dopamine D3 receptor-preferring D3/D2 partial agonist antipsychotic that is approved for the treatment of schizophrenia (USA and EU) and manic/mixed and depressive episodes associated with bipolar I disorder (USA). |

The efficacy and safety of cariprazine in schizophrenia were demonstrated in four short-term randomized clinical trials, two long-term open-label safety studies, one relapse prevention study, and one prospective study in patients with persistent predominant negative symptoms. |

In post hoc analyses, cariprazine has also shown broad-spectrum efficacy across individual symptoms and domains of schizophrenia, as well as in diverse areas of interest including cognitive symptoms, negative symptoms, and functioning. |

In all clinical trials, cariprazine was generally safe and well tolerated in patients with acute and long-term exposure, with no new safety concerns revealed in longer-term treatment. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14588418.

Introduction

Schizophrenia, a serious central nervous system disorder that affects approximately 1% of the world’s population [1], is characterized by diverse symptom domains: positive symptoms (e.g., hallucinations, delusions), negative symptoms (e.g., social and emotional withdrawal, anhedonia), cognitive dysfunctions (e.g., attention deficit, executive function impairment), and comorbid affective symptoms (i.e., depression and anxiety) [2, 3]. Although antipsychotic medications are the foundation of pharmacotherapy for schizophrenia, they are primarily effective against positive symptoms, which means that negative, cognitive, and affective symptoms remain as unmet treatment needs [4, 5]. Since symptoms from these domains significantly affect functional well-being and patient quality of life [6,7,8], an antipsychotic with broad-spectrum efficacy is needed to provide comprehensive symptom management for patients with schizophrenia.

Early success in the treatment of schizophrenia was initiated by the discovery of first-generation antipsychotics (i.e., neuroleptics) [9]. These agents work by blocking the dopamine D2 receptor and, while they are mainly effective against the positive symptoms of schizophrenia, they are commonly associated with serious and treatment-limiting adverse effects including extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) [9]. In the mid-1990s, second-generation or atypical antipsychotics were introduced; although there is no consensus definition for the term “atypical,” it was originally used to describe antipsychotics with lower or minimal risk of causing EPS [10]. Pharmacologically different than first-generation antipsychotics, atypical agents are a heterogenous class of drugs that have less specific antagonistic activity at the D2 receptor, relatively stronger serotonin 5-HT2A receptor action, and variable effects on other receptor subtypes; different pharmacological profiles account for vast differences in safety and tolerability profiles among the agents in the class [11, 12]. Although atypical antipsychotics have largely replaced conventional agents for schizophrenia treatment [13], no breakthrough negative or cognitive symptoms efficacy has been noted [5] and all agents are associated with some degree of EPS [14]. Other undesirable side effects such as weight gain, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular side effects are also a considerable concern with some agents [9].

Most recently, atypical antipsychotic agents with novel dopamine D2 receptor partial agonist pharmacology have been advanced as “third-generation” antipsychotics [9, 15]. Partial agonists have a lower intrinsic activity at receptors than full agonists, which enables them to act as either functional agonists or functional antagonists depending on the surrounding neurotransmitter environment [16]. In schizophrenia, a D2 receptor partial agonist behaves as a functional antagonist in the mesolimbic dopamine pathway where hyperdopaminergic activity is thought to cause positive symptoms, while acting as a functional agonist in the mesocortical pathway where hypodopaminergic activity is thought to cause negative symptoms and cognitive dysfunction [16]. Aripiprazole, the first of these agents introduced, is distinguished from earlier antipsychotics by partial agonist activity at D2, D3, 5-HT1A, and 5-HT2C receptors [17]. Cariprazine, a more recent member of this distinct group of antipsychotics, has a unique receptor profile characterized by dopamine D3-preferring D3/D2 receptor partial agonism and serotonin 5-HT1A partial agonism. Although cariprazine and aripiprazole are both partial agonists at dopamine D2 and D3 receptors, cariprazine is more selective for the D3 versus D2 receptor, while aripiprazole has greater selectivity for D2 receptors [18]. Cariprazine is approved to treat adults with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia (EU and USA) and mixed or manic and depressive episodes associated with bipolar I disorder (USA).

This comprehensive review provides an overview of the unique pharmacology of cariprazine in the context of its clinical studies and numerous post hoc analyses that have added to the cariprazine evidence base across symptomatic and functional domains in schizophrenia. Additionally, since efficacy is only meaningful if the medication has a good tolerability and usability profile, the short- and long-term safety data for cariprazine are also summarized across studies.

Cariprazine Pharmacology

Mechanism of Action

The discovery and characterization of the dopamine D3 receptor subtype advanced the possibility of finding and developing new types of antipsychotic drugs that could provide a more effective and better-tolerated target for the treatment of psychotic disorders than the previously used D2 receptor antagonists [19, 20]. Cariprazine was developed on the basis of the hypotheses that, although dopamine D2 affinity is an indispensable antipsychotic property, compounds with dopamine D3 antagonism/partial agonism may provide additional benefits in the treatment of schizophrenia [21]. Cariprazine is a partial agonist at the dopamine D2 and D3 receptors and serotonin 5-HT1A receptors and an antagonist at the 5-HT2B receptors, with moderate affinity for adrenergic, histaminergic, and cholinergic receptors [22]. Differing from other antipsychotics, cariprazine has a higher potency for the D3 receptor than does dopamine itself, resulting in full D3 receptor occupancy at clinically relevant doses [23]. Cariprazine has almost tenfold greater affinity for D3 than D2 receptors in vitro [18], with high in vivo occupancy at both dopamine D2 and D3 receptors at clinically relevant doses [24, 25]. In animal studies, cariprazine has demonstrated clear dopamine D3 receptor-dependent procognitive and anti-anhedonic effects, suggesting potential efficacy against negative and cognitive symptoms in patients [26, 27].

In human positron emission tomography (PET) studies, the in vivo dopamine D2 and D3 receptor binding profile for cariprazine has been elucidated in healthy volunteers (using [11C]raclopride) and in patients with schizophrenia (using [18F]fallypride) [28]. In an another PET study in patients with schizophrenia, cariprazine bound to both D3 and D2 receptors in a dose-dependent manner, and receptor occupancy data confirmed in vivo D3 receptor dominance (3.43- to 5.75-fold) using [11C]-(+)-PHNO [24]. While other atypical antipsychotics also show significant affinity for both D2 and D3 receptors in vitro, they are unable to inhibit PET ligand binding to D3 receptors alone in vivo [29,30,31]. Since the dopamine D3 receptor is preferentially expressed in the mesolimbic circuit, it has been identified as a potential target for treating negative, cognitive, and mood symptoms associated with schizophrenia [32,33,34,35,36]. These pharmacological characteristics form the basis from which the clinical profile of cariprazine emerges; understanding the intricacies of its partial agonist profile may help explain negative and cognitive symptom improvement seen in clinical trials of patients with schizophrenia.

Pharmacokinetic Properties

Cariprazine is a once-daily oral medication taken with or without food. It has two major active metabolites, desmethyl cariprazine (DCAR) and didesmethyl cariprazine (DDCAR), which are pharmacologically equipotent to cariprazine and jointly responsible for the overall therapeutic effect [37, 38]. The pharmacokinetics of cariprazine were characterized in a randomized, open-label, parallel-group, fixed-dose (3, 6, or 9 mg/day) study [38]. Steady state was reached in 1–2 weeks for cariprazine and DCAR, 4 weeks for DDCAR, and 3 weeks for total active moieties. Levels of cariprazine and DCAR decreased by more than 90% within 1 week after the last dose, while DDCAR decreased by ca. 50% at 1 week; the total active moieties decreased by ca. 90% within 4 weeks [38]. Terminal half-lives ranged between 31.6 and 68.4 h for cariprazine, 29.7–37.5 h for DCAR, and 314–446 h for DDCAR. The effective half-life of the total active moieties, based on time to reach steady state, was ca. 1 week [38]. Cariprazine is extensively metabolized by CYP3A4 and, to a lesser extent, by CYP2D6 to DCAR and DDCAR. The effect of CYP3A4 inducers on the exposure of cariprazine has not been evaluated, and the net effect is unclear. Because concomitant use of cariprazine with a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor increases the exposures of cariprazine and DDCAR compared to the use of cariprazine alone, a reduced cariprazine dose is recommended [39].

Cariprazine: Clinical Trial Overview

The efficacy and safety of cariprazine in treating adult patients with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia were established in four short-term randomized clinical studies, two long-term open-label studies, one relapse prevention study, and one negative symptom study. All cariprazine study protocols were approved by the relevant institutional review boards (US sites) or ethics committee (non-US sites); ICH-E6 Good Clinical Practice guidelines were followed and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Short-Term Efficacy Studies

The acute efficacy of cariprazine in schizophrenia was demonstrated in four randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter, international, 6-week studies [40,41,42,43]. The primary efficacy endpoint in each study was mean change from baseline to week 6 in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score [44]; the secondary endpoint was change in Clinical Global Impressions-Severity (CGI-S) score [45]. Included patients (18–60 years of age [18–65 in RGH-MD-03]) had current exacerbation less than 2 weeks in duration (less than 4 weeks in RGH-MD-03), a CGI-S score of at least 4 (moderately ill or worse), PANSS total score between 80 and 120, and a score of at least 4 (moderate or higher) on at least two specified PANSS items (hallucinatory behavior, suspiciousness/persecution, delusions, and conceptual disorganization). Exclusion criteria were typical of clinical studies in schizophrenia and included the presence of various other psychiatric diagnoses (e.g., schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorders), treatment-resistant schizophrenia, substance abuse, and active suicidal intent or past attempt within 2 years. Concurrent medical conditions that could interfere with the conduct of the study, confound the interpretation of results, or endanger the patient’s well-being were also exclusionary.

Proof-of-Concept Study (RGH-MD-03)

This 6-week, flexible-dose, double-blind, placebo-controlled, proof-of-concept study was conducted to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of high- and low-dose cariprazine in patients with acute schizophrenia [41]. The primary endpoint of the study was evaluated in the intent-to-treat (ITT) population using the last observation carried forward (LOCF). Completion rates were similar among treatment groups. No statistically significant differences were found for the overall comparison between cariprazine and placebo after adjustment for multiplicity on any efficacy outcome. However, when pairwise comparisons were evaluated without correcting for multiplicity, low-dose cariprazine (1.5–4.5 mg/day) was significantly different than placebo on change from baseline in PANSS total score (Table 1) and PANSS negative subscale score (P = 0.027); the difference between cariprazine 6–12 mg/day and placebo in PANSS total score was not significant (P = 0.100). Given this positive efficacy signal for lower dose cariprazine, further investigation of cariprazine as a potential treatment for schizophrenia was warranted.

Phase 2 Dose-Finding Study (RGH-MD-16)

On the basis of the results of the proof-of-concept study, a fixed-dose, multinational, double-blind, randomized, placebo- and active-controlled dose-finding study in patients with acute schizophrenia was initiated [42]. Primary efficacy analyses were based on the ITT population using an LOCF approach in patients randomized to placebo, cariprazine: 1.5 mg/day, 3 mg/day, 4.5 mg/day, or risperidone 4 mg/day; risperidone was included for assay sensitivity. Approximately 64% of patients completed the study. The difference in PANSS total score and CGI-S change from baseline was statistically significant in favor of each cariprazine dose versus placebo using the LOCF approach (Table 1); sensitivity analyses using a mixed-effects model for repeated measures (MMRM) supported the primary outcomes (least squares mean difference [LSMD] 1.5 mg/day = − 8.0 (− 12.9, − 3.0); 3.0 mg/day = − 8.2 (− 13.1, − 3.2); 4.5 mg/day = − 10.5 (− 15.4, − 5.6); P < 0.01 each). Differences in CGI-S change were also significant for all cariprazine doses versus placebo (P < 0.05); differences for risperidone versus placebo were also statistically significant on the primary and secondary efficacy outcome.

Phase 3 Efficacy Study 1 (RGH-MD-04)

In this multinational, randomized, 6-week, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled, fixed-dose phase 3 clinical trial, patients with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia received placebo, cariprazine 3 mg/day, cariprazine 6 mg/day, or aripiprazole 10 mg/day; aripiprazole was included for assay sensitivity [40]. Efficacy analyses were based on the ITT population using an MMRM approach. Approximately 67% of patients completed the study. Differences versus placebo in change from baseline to week 6 in PANSS total score were statistically significant in favor of cariprazine 3 mg/day and 6 mg/day; similarly, differences in CGI-S score were also significant for both cariprazine groups versus placebo (Table 1). Aripiprazole was also significantly different than placebo on PANSS total score and CGI-S.

Phase 3 Efficacy Study 2 (RGH-MD-05)

In a second phase 3, 6-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study, the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of fixed/flexible doses cariprazine were evaluated in patients with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia [43]. Efficacy analyses were based on the ITT population using an MMRM approach. The study was completed by 59.9%, 63.6%, and 58.1% of placebo-treated, cariprazine 3–6 mg/day, and cariprazine 6–9 mg/day patients, respectively. At the end of week 6, the difference in PANSS total score was statistically significant in favor cariprazine 3–6 mg/day and 6–9 mg/day; differences in CGI-S score versus placebo were also significant for cariprazine 3–6 mg/day and cariprazine 6–9 mg/day (Table 1).

Long-Term Efficacy Studies

Relapse Prevention (RGH-MD-06)

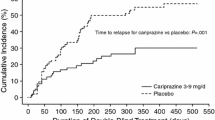

The efficacy of cariprazine for the prevention of relapse in patients with acute schizophrenia was evaluated in a multicenter, international, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, relapse prevention phase 3 clinical trial of up to 97 weeks’ duration (NCT01412060) [46]. The primary efficacy parameter was time to relapse defined as worsening of symptom scores, psychiatric hospitalization, aggressive/violent behavior, or suicidal risk. Open-label cariprazine 3–9 mg/day was administered to 765 patients during a 20-week stabilization phase; 200 patients completed open-label treatment with stable symptoms and were eligible to be randomized to double-blind placebo (n = 99) or continued cariprazine 3, 6, or 9 mg/day (n = 101) for up to 72 weeks. Time to relapse was significantly longer for patients treated with double-blind cariprazine (224 days) than for patients switched to placebo (92 days) (P = 0.0010), with the rate of relapse 24.8% for cariprazine and 47.5% for placebo.

In additional analyses, the relapse rate of patients with schizophrenia who were treated with cariprazine in the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommended 3–6 mg/day dose range was investigated [39]. A total of 337 enrolled patients were stabilized on cariprazine 3–6 mg/day; of stabilized patients, 51 received fixed-dose cariprazine 3 or 6 mg/day and 51 received placebo. By the end of the study, 49.0% of placebo-treated patients and 21.6% of cariprazine-treated patients experienced a relapse event. The time to relapse was significantly longer for cariprazine (326 days) than for placebo (92 days) (P = 0.009).

Schizophrenia with Predominant Negative Symptoms (RGH-188-005)

Negative symptoms of schizophrenia are a core feature of schizophrenia and, although they can be severe enough to interfere with normal functioning, they are only marginally responsive to antipsychotic treatment [47, 48]. The efficacy of cariprazine versus the active comparator risperidone was investigated in adult patients with stable schizophrenia and persistent (at least 2 years) and predominant (more than 6 months) negative symptoms (EudraCT 2012-005485-3) [49]. To exclude the possibility that negative symptom improvement was secondary to improvements in other symptom domains (i.e., pseudospecific), patients were excluded if they had significant positive symptoms, moderate/severe depressive symptoms, or clinically relevant EPS. A total of 461 patients (cariprazine = 230; risperidone = 231) with moderate-to-severe negative symptoms were randomized to cariprazine (target dose = 4.5 mg/day) or risperidone (target dose = 4 mg/day) in a 26-week, multinational, multicenter, randomized, double-blind study. The primary and secondary efficacy parameters were change from baseline to week 26 in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale-Factor Score for Negative Symptoms (PANSS-FSNS) [50] and Personal and Social Performance Scale (PSP) [51], respectively, analyzed using an MMRM approach. The difference in PANSS-FSNS score at week 26 was statistically significant in favor of cariprazine versus risperidone (P = 0.0022) (Table 2); the effect size versus risperidone was 0.31. Improved patient functioning was also demonstrated for cariprazine versus placebo by statistically significant differences in PSP total (P < 0.0001), with an effect size of 0.48. Significant differences for cariprazine versus risperidone were also seen across all PSP subdomains reflecting negative symptoms (i.e., self-care, socially useful activity, personal and social relationships) scores (P < 0.01 each); a between-group difference in the aggressive behavior subdomain was not expected or observed because of the exclusion of patients with exacerbated positive symptoms (Table 2). Importantly, because negative symptom change is not considered clinically relevant unless it is accompanied by functional improvement, these PSP changes are important outcomes of note. On the basis of these clinical data, cariprazine was recommended as the first-choice treatment for predominantly negative symptomatic in patients with schizophrenia [52].

Post Hoc Efficacy Analyses

To further inform the evidence base for cariprazine, several post hoc analyses have been conducted across a variety of areas relevant to schizophrenia. In the three phase 2/3 acute studies of cariprazine in schizophrenia [40, 42, 43], similar designs, inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, and outcome parameters allowed the data to be pooled to assess the efficacy of cariprazine across diverse outcomes and domains; in most post hoc investigations, analyses were based on the pooled ITT population using an MMRM approach with no correction for multiplicity. Efficacy has been further evaluated in post hoc analyses of data from the long-term relapse prevention [46] and the negative symptom [49] studies.

Broad-Spectrum Efficacy Across Symptom Domains

Because schizophrenia is associated with diverse symptom domains, changes in PANSS-derived symptom factors (positive symptoms, negative symptoms, disorganized thought, uncontrolled hostility/excitement, and anxiety/depression) and individual items were evaluated for cariprazine versus placebo using pooled data from the three acute schizophrenia studies [53]. Statistically significant differences in change from baseline to week 6 were observed in favor of cariprazine versus placebo on all five PANSS symptom factors (P < 0.01 all factors) with effect sizes ranging from 0.21 (anxiety/depression) to 0.47 (disorganized thought). In a dose–response analysis using data from the two fixed-dose studies [40, 42], significant differences in PANSS total score, negative symptom factor, and disorganized thought factor change were observed across all cariprazine doses (1.5, 3.0, 4.5, 6.0 mg/day) versus placebo (P < 0.001). Additionally, significant improvement for cariprazine versus placebo was also noted on 26 of 30 PANSS individual items (P < 0.05). Collectively, these results demonstrate that cariprazine has broad-spectrum efficacy across the domains and symptoms of acute schizophrenia.

Hostility

Although most patients with schizophrenia are not aggressive, some patients have an increased risk of hostile or aggressive behavior [54]. To investigate the efficacy of cariprazine in patients with schizophrenia and hostility, a post hoc analysis of pooled data from the three acute studies assessed PANSS item P7 (hostility) in the pooled overall ITT population, when adjusted for certain covariates, and in baseline hostility subsets [55]. The LSMD in change from baseline to week 6 in PANSS hostility item was statistically significant in favor of cariprazine versus placebo in the overall, unadjusted analysis (− 0.28 [− 0.41, − 0.15]; P < 0.0001), when adjusted for PANSS positive symptoms (− 0.12 [− 0.4, − 0.2]; P < 0.05), and when adjusted for positive symptoms plus sedation (− 0.12 [− 0.4, − 0.2]; P < 0.05). The magnitude of change for cariprazine increased across three levels of increasing baseline hostility, with a statistically significant difference seen at each severity level analyzed (P < 0.01 each).

Global Illness Severity

The CGI-S is a global measurement that uses informed clinical judgment to assess illness severity, level of distress and impairment, and the impact of the illness on functioning [56]. To better characterize the clinical relevance of cariprazine in improving disease severity in patients with schizophrenia, data from the three acute efficacy trials were pooled for post hoc analysis [57]. Cariprazine- and placebo-treated patients were categorized by baseline CGI-S scores and the proportion of patients who improved from more severe categories at baseline to less severe categories at study endpoint was evaluated. After 6 weeks of treatment, the most common CGI-S score for cariprazine-treated patients corresponded to mild illness regardless of baseline disease severity scores; a small percentage of patients with severe/extreme or marked baseline illness scores attained scores corresponding to normal. Additionally, more placebo- than cariprazine-treated patients had worse end of treatment scores in both disease states. More cariprazine patients than placebo patients shifted from the extremely/severely ill category to the mildly ill/better category (42% vs 18%, odds ratio [OR] = 3.4 [1.5, 7.9], P < 0.01); ORs were also statistically significant in favor of cariprazine for shifts from marked illness to borderline/normal (OR = 2.3 [1.1, 4.8], P < 0.05) and from moderate illness to borderline/normal (OR = 1.6 [1.0, 2.7], P < 0.05). In these post hoc analyses, treatment with cariprazine produced clinically relevant, as well as statistically significant, improvement in patients with schizophrenia.

Relapse and Sustained Remission

Since the chronic nature of schizophrenia may necessitate treatment throughout the lifetime, symptom stability is an important component of comprehensive illness management [58]. Long-term remission with cariprazine was investigated in a post hoc analysis of data from the constituent relapse prevention study [59]. Symptomatic remission criteria (scores ≤ 3 on eight items of the PANSS General, Positive, and Negative Subscales) and sustained remission was defined as meeting symptomatic criteria for a specified period of time. At randomization, 84.5% (169/200) of patients met the criteria for symptomatic remission. During double-blind treatment, time to loss of sustained remission was significantly longer for cariprazine-treated patients than placebo-treated patients (P = 0.0020; hazard ratio = 0.51 [0.33, 0.79]). A total of 60.5% of cariprazine-treated patients and 34.9% of placebo-treated patients remained in remission until the last visit (OR = 2.85 [1.52, 5.32]; P = 0.0012; number needed to treat [NNT] = 4). More cariprazine-treated patients (41.6%) than placebo-treated patients (27.3%) sustained remission for 6 consecutive months before their last visit in remission (OR = 1.90 [1.05, 3.44], P = 0.0379; NNT = 7) and almost twice as many cariprazine- (39.6%) versus placebo-treated patients (21.2%) met remission criteria for at least 6 consecutive months including their last study visit (OR = 2.44 [1.30, 4.55]; P = 0.0057; NNT = 6). Overall, cariprazine compared with placebo was characterized by significantly longer sustained remission, higher remission rates, and higher uninterrupted remission for at least one half year.

When cariprazine and its two major active metabolites (DCAR and DDCAR) are taken into account, the effective half-life for the total active moieties is approximately 1 week [38]. This long half-life, compared with other oral antipsychotics, may offer some continued treatment effect after drug discontinuation, which could provide protection against rapid onset of relapse in cases of nonadherence. To explore the timing of relapse following drug discontinuation relative to estimated plasma levels and elimination half-life, data from the cariprazine relapse study [46] was compared with data from similarly designed randomized control trials of other oral atypical antipsychotics [60]. Kaplan–Meier curves were used to estimate the time to separation of the drug–placebo curves; separation was defined as a sustained difference of at least 5% incidence of relapse between the antipsychotic and placebo curves. Separation of the cariprazine and placebo relapse curves occurred 6–7 weeks after randomization into double-blind treatment, while separation of other antipsychotics and placebo was estimated to occur much sooner (1–4 weeks). Four weeks after randomization, the relapse rate for patients switched to placebo for double-blind treatment was 5% in the cariprazine study and 8–34% in the studies of other antipsychotics. The model-predicted plasma concentrations of cariprazine suggested that cariprazine may continue to occupy D2 and D3 receptors at 2 and 4 weeks after the last dose, while other antipsychotics, whose half-lives are less than 4 days, would be expected to have low or negligible plasma concentration at these time points. The incidence of relapse after treatment discontinuation appeared to be delayed for cariprazine compared with other antipsychotics, suggesting that the longer half-life of cariprazine and its active metabolites may be associated with a delayed incidence of relapse.

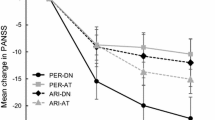

Negative Symptoms

The lack of effective treatments for the negative symptoms of schizophrenia is considered a significant unmet medical need. Post hoc analyses of data from two acute cariprazine clinical studies [40, 42] investigated the potential for efficacy in a subset of patients with exacerbation of schizophrenia and moderate/severe negative symptoms; risperidone and aripiprazole were included in the constituent studies to confirm assay sensitivity [61]. Changes from baseline to week 6 in PANSS-FSNS, the negative symptom factor score, were significantly different than placebo for cariprazine 1.5–3 mg/day (P = 0.0179), 4.5–6 mg/day (P = 0.0002), and risperidone (P = 0.0149); aripiprazole was not significantly different than placebo (P = 0.3265), while a significant difference was noted in favor of cariprazine 4.5–6 mg/day versus aripiprazole (P = 0.0197). After adjustment for changes in positive symptoms, differences versus placebo remained statistically significant for cariprazine (1.5–3 mg/day, P = 0.0322; 4.5–6 mg/day, P = 0.0038), but not for risperidone (P = 0.2204), suggesting that improvement in negative symptoms for cariprazine was at least partially independent of improvements in positive symptoms. This is an important observation since improvement in negative symptoms often occurs secondary to improvement in other symptom domains, making it difficult to identify actual treatment effects for primary negative symptoms. Of note, this pooled analysis, which provided an initial signal that cariprazine may offer efficacy in negative symptoms, supports the subsequent efficacy advantage demonstrated for cariprazine versus risperidone in the 26-week prospective study of patients with persistent and predominant negative symptoms of schizophrenia [49].

Post hoc analyses have also been conducted on data from the negative symptom study (RGH-188-005) to further inform these outcomes. Individual PANSS items and PANSS-derived symptom factors were evaluated using an MMRM approach in the ITT population (cariprazine = 227; risperidone = 227) [62]. On the individual items of the PANSS negative subscale, differences were statistically significant in favor of cariprazine versus risperidone on items N1 (blunted affect), N2 (emotional withdrawal), N3 (poor rapport), N4 (passive/apathetic social withdrawal), and N5 (difficulty in abstract thinking) (P < 0.05 all); no between-group differences were seen on items N6 (lack of spontaneity/continuity of conversation) and N7 (stereotypical thinking). Of the individual items that make up the PANSS-FSNS, significant differences were again seen on negative symptoms items N1 through N4, but not on N6, and General Psychopathology subscale item G16 (active social avoidance; P < 0.05), but not on item G7 (motor retardation). Differences were also statistically significant for cariprazine versus risperidone on several other PANSS-derived negative symptom factors (i.e., Liemburg factor, Khan factor, pentagonal structure model negative symptom factor; P < 0.05 each factor). On PANSS-based factors assessing changes in other symptom domains that are relevant to negative symptoms, significant differences in mean change from baseline were seen for cariprazine over risperidone on the Marder disorganized thoughts factor, the prosocial functioning factor, and the Meltzer cognitive subscale (P < 0.05 for each factor) [62, 63]. Of note, a pseudospecificity analysis found that changes in factors related to positive symptoms, depressive/anxious symptoms, and uncontrolled excitement and hostility were small and similar for cariprazine and risperidone, confirming that improvement in negative symptoms was not secondary to improvement in other symptoms.

The long-term efficacy of cariprazine on negative symptoms has been investigated in a subset of patients with moderate-to-severe negative symptoms using data from the two long-term, open-label cariprazine safety studies [64, 65]; supportive analyses were conducted on data from the relapse prevention trial [46]. In the pooled 48-week open-label study population, PANSS-FSNS scores decreased over time, with the majority of change occurring during the first 8 weeks of treatment (least squares mean [LSM] change at week 8, − 9.0) and maintained through the remaining 40 weeks (LSM change at week 48, − 11.1) [66]. Results were similar in the supportive analysis of 20-week open-label relapse prevention data, with the majority of change occurring in the first 12 weeks of treatment (LSM change from baseline, week 8 = − 10.5; week 12 = − 11.5; week 20 = − 12.1). These results extend the findings of previous analyses and suggest that cariprazine-associated negative symptom improvement could persist for up to a year.

Cognition

Neurocognitive impairment is a core feature of schizophrenia; deficits in cognitive functioning are associated with worse outcomes and diminished quality of life, including longer illness duration, negative symptoms, and lower psychosocial functioning [67, 68]. The positive effect of cariprazine on cognitive symptoms in patients with schizophrenia has been noted in pooled post hoc analyses of the three acute studies where differences in change from baseline to week 6 for cariprazine 1.5–9 mg/day versus placebo were statistically significant on the PANSS disorganized thought factor (P < 0.0001) [53], the PANSS cognitive subscale (P < 0.001) [69], and on each individual item of the cognitive subscale (P < 0.001 each item) [69]. Further, improvement in cognitive symptoms in patients with schizophrenia and persistent predominant negative symptoms was demonstrated by statistically significant differences in change from baseline to week 26 in favor of cariprazine 4.5 mg/day versus risperidone 4.0 mg/day (the active comparator) on the PANSS disorganized thought factor (P < 0.05) and PANSS cognitive subscale (P < 0.05) [62].

Of additional interest, an objective measure of cognitive change was provided by findings from the Cognitive Drug Research (CDR) System Attention Battery [70], which was administered as an additional efficacy measure to patients in phase 3 study RGH-MD-04 [40]. For patients with baseline attentional impairment, significantly greater median change from baseline was noted for cariprazine 3 mg/day versus placebo (P < 0.01), as well as for cariprazine versus the active comparator aripiprazole (P < 0.01), on the power of attention factor, a focused attention measure [40]. Significant improvement for cariprazine 3 mg/day and 6 mg/day versus placebo (P < 0.01) was also seen on the continuity of attention factor, a sustained attention measure in patients with baseline impairment.

Functional Outcomes

Day-to-day functioning is an important component of quality of life and well-being for patients with schizophrenia. Symptoms of schizophrenia, especially those from the negative and depressive symptom domains, are associated with severe social and occupational dysfunction and subsequent detrimental effects on patients’ quality of life [71]. In a pooled analysis of data from the two short-term phase 3 trials [40, 43], quality of life in patients experiencing an acute exacerbation of schizophrenia was evaluated using the Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale Revision 4 (SQLS-R4) total score and the vitality and psychosocial factor scores [72]. The between-group difference was statistically significant in favor of cariprazine versus placebo for change from baseline to week 6 on SQLS-R4 total score (P < 0.0001), vitality factor score (P < 0.0001), and psychosocial factor score (P = 0.0007) [73]. Results of these post hoc analyses suggest that quality of life benefits may have been associated with symptom improvement for cariprazine-treated patients with schizophrenia.

An additional post hoc analysis of data from a phase 3 cariprazine study (RGH-MD-04) [40] was conducted to evaluate psychosocial functioning in patients with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia [74]. The difference in change from baseline on the PANSS-derived prosocial factor score was statistically significant in favor of cariprazine versus placebo at week 1 for the 6 mg/day dose and week 3 for the 3 mg/day dose; statistical differences in both groups were maintained through week 6. Significant differences versus placebo were observed for both doses of cariprazine on three items (emotional withdrawal, passive/apathetic social withdrawal, active social avoidance) and on one additional item for cariprazine 6 mg/day (suspiciousness/persecution); differences were not significant for hallucinatory behavior and stereotyped thinking items. Results suggest that previously demonstrated efficacy across multiple symptom domains (e.g., negative and cognitive symptoms) may contribute to improved psychosocial functioning in patients with acute exacerbations of schizophrenia.

In longer-term treatment, functional improvement was also investigated via post hoc analyses of PSP total and subdomain outcomes in the relapse prevention trial [46]. Marked and clinically relevant PSP total score improvement was noted for patients who were stabilized on cariprazine during the open-label phase of the trial (+19 point) versus patients who did not stabilize during open-label treatment (+8 points) [75]. After stabilized patients entered double-blind treatment, those randomized to placebo experienced worsening of PSP outcomes, while cariprazine-treated patients remained basically unchanged, with statistically significant differences in favor cariprazine seen in PSP total score (P < 0.001) and each subdomain score (self-care, socially useful activity, personal and social relationships, aggressive behavior; P < 0.01). These post hoc outcomes are consistent with results from the negative symptom trial [49], which showed a statistically significant difference in favor of cariprazine versus risperidone on PSP total score and in each subdomain relevant to the study (self-care, socially useful activity, personal and social relationships).

Severity and Stage of Illness

Because the ability to effectively treat patients across differing levels of severity and illness progression is an important antipsychotic attribute, the efficacy of cariprazine across these illness characteristics has been investigated in post hoc analyses of pooled data from three acute cariprazine treatment trials [40, 42, 43]. Illness severity was evaluated by change from baseline in PANSS outcomes (total score, negative and positive subscale scores) and CGI-S score in patient subgroups categorized by baseline severity [76]. Across outcomes, cariprazine was more effective than placebo in reducing schizophrenia symptoms and global disease severity regardless of baseline symptom severity, with greater treatment effects observed in subgroups with more severe symptoms. Additional analyses evaluated cariprazine versus placebo in subgroups of patients stratified by stage of illness defined by the number of previous episodes, duration of schizophrenia, or number of previous psychiatric hospitalizations. Relative to placebo, cariprazine-treated patients in the latest stage of illness experienced similar or greater efficacy than patients at the earliest stage, suggesting that cariprazine is effective in schizophrenia regardless of disease progression [77]. Collectively, cariprazine appears to be a beneficial treatment for patients with schizophrenia across levels of baseline illness severity and regardless of stage of illness.

Safety Investigations

Acute and long-term exposure to cariprazine in patients with schizophrenia was generally safe and well tolerated. No new safety concerns were revealed during long-term treatment and adverse events (AEs) were consistent with those associated with atypical antipsychotic treatment. One significant and accidental overdose has been reported in cariprazine clinical trials. In a patient with schizophrenia, orthostasis and sedation were observed with cariprazine 48 mg/day, which resolved on the day of overdose [39].

Short-Term Safety Analysis

The safety and tolerability of cariprazine has been evaluated in a post hoc analysis of data from the proof-of-concept study and the three phase 2/3 studies in acute patients [78]. Analyses were performed in the overall safety population, which included 1317 cariprazine patients and in modal daily dose subgroups (1.5–3 mg/day = 539, 4.5–6 mg/day = 575, and 9–12 mg/day = 203) using descriptive statistics. A dose response was noted for the incidence of treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs), with similar rates for cariprazine 1.5–3 mg/day (68.6%) and placebo (69.0%), and higher rates for cariprazine 4.5–6 mg/day (76.9%) and 9–12 mg/day (84.7%). The most common TEAEs for overall cariprazine were EPS (17.4%), insomnia (12.3%), akathisia (11.3%), and headache (11.2%); the incidence of headache was greater in placebo (12.7%) than in overall cariprazine. A dose–response relationship was also seen for akathisia, extrapyramidal symptoms, and diastolic blood pressure. Mean changes in metabolic parameters were generally similar in cariprazine- and placebo-treated patients. No increase in prolactin levels or QTc values greater than 500 ms were observed, while a small increase in mean body weight (ca. 1–2 kg) was observed relative to placebo. Pooled analysis demonstrated that cariprazine was generally safe and well tolerated in patients with schizophrenia, with a dose–response noted in the incidence of some AEs.

Long-Term Safety

Pooled Open-Label, Long-Term Safety Studies

Two long-term, multicenter, open-label, flexible-dose studies were conducted to assess the safety and tolerability of cariprazine in patients who had completed a 6-week acute lead-in study or were newly enrolled (NCT00839852 [RGH-MD-17] and NCT01104792 [RGH-MD-11]) [64, 65]. Included patients were required to have stable symptoms (at least 20% reduction in PANSS total score from lead-in study baseline [RGH-MD-17] or PANSS positive subscale score ≤ 25 [RGH-MD11]) and CGI-S score ≤ 3.

Pooled data from these long-term, open-label safety studies were analyzed in the overall cariprazine safety population and in modal daily dose groups of 1.5–3 mg/day, 4.5–6 mg/day, and 9 mg/day [79]. A total of 679 patients were included in the overall population and 40.1% completed the study; withdrawal of consent (n = 25.0%) and AEs (n = 12.2%) were the most common reasons for study discontinuation. Akathisia, exacerbation of schizophrenia, and psychotic illness were the only AEs that led to discontinuation of at least 2% of patients. TEAEs were reported by 81.7% of overall cariprazine patients (1.5–3 mg/day = 82.9%; 4.5–6 mg/day = 79.5%; 9 mg/day = 85.8%), with akathisia, insomnia, weight gain, and headache reported in at least 10% of patients overall. AEs were mild or moderate in 71.1% of patients overall (1.5–3 mg/day = 74.1%; 4.5–6 mg/day = 70.1%; 9 mg/day = 70.3%). The most commonly reported serious AEs (SAEs) were worsening of schizophrenia (4.4%) and psychotic disorder (2.1%). EPS-related TEAEs that occurred in at least 5% of patients overall were akathisia, tremor, restlessness, and extrapyramidal disorder.

Mean change in prolactin levels was − 15.4 ng/ml for cariprazine overall (1.5–3 mg/day = − 13.6; 4.5–6 mg/day = − 17.1; 9 mg/day = − 13.3). Changes in aminotransferase and alkaline phosphatase levels were not clinically significant and did not show a dose relationship. Total cholesterol (− 5.3 mg/dL), low-density lipoprotein (− 3.5 mg/dL), and high-density lipoprotein (− 0.8 mg/dL) levels decreased and again showed no dose dependence. Mean weight gain was 1.58 kg; weight increase and decrease of at least 7% were 27% and 11%, respectively. Cardiovascular parameters, including mean changes in blood pressure and heart rate, were generally not clinically significant. Findings based on the combined data from two long-term safety studies supported previously reported safety and tolerability outcomes for cariprazine in adult patients with schizophrenia.

Safety and Tolerability in Recommended Dose Range

The safety of cariprazine in the therapeutic 1.5 to 6 mg/day dose range was characterized in a post hoc analysis of pooled data from the short- and long-term treatment trials of cariprazine in schizophrenia [80]. The safety data analyzed represented a total of 2048 cariprazine-treated patients and 683 placebo-treated patients from eight studies (one proof-of concept study; three phase 2/3 6-week studies, the negative symptoms study, two long-term open-label safety studies, and one relapse prevention trial) [40,41,42,43, 46, 49, 64, 65].

Common TEAEs (at least 5% and twice the rate of placebo) for cariprazine versus placebo were akathisia (14.6% vs 3.4%), extrapyramidal AEs (7.0% vs 3.2%), and weight gain (5.1% vs 1.5%) [80]. Although akathisia occurred at a considerably higher rate in cariprazine than in placebo, the characterization of severity was similar in both groups. For cariprazine and placebo, the majority of cases were considered mild (53.9% and 60.8%) or moderate (43.5% and 34.8%) and the proportion of severe cases was low (2.6% and 4.4%); akathisia-related discontinuations occurred in less than 1% of cariprazine-treated patients [81]. Other AEs that occurred with similar incidence for cariprazine and placebo were insomnia (14.0% vs 10.1%), headache (12.1% vs 11.9%), anxiety (6.9% vs 4.0%), and sedation (3.7% and 3.1%) [80, 82].

Cariprazine had a neutral metabolic profile. In the short-term clinical trials, a lower percentage of cariprazine- than placebo-treated patients shifted from normal to high levels of LDL cholesterol (2.9% vs 4.9%) and fasting triglyceride (6.7% vs 8.3%), while a higher percentage of cariprazine-treated patients (6.7%) than placebo-treated patients (3.6%) shifted from normal to high levels of fasting glucose [83]. In long-term use, similar percentages of cariprazine- and placebo-treated patients shifted from normal to high levels of LDL cholesterol (2.0% vs 2.0%) and fasting triglyceride (10.7% vs 12.5%), while a higher percentage of cariprazine-treated patients (6.2%) than placebo-treated patients (1.0%) again shifted from normal to high levels of fasting glucose. Of note, the rate of fasting glucose increase did not differ between the short- and long-terms. During long-term treatment, weight gain remained stable (ca. 1.1 kg/year) in cariprazine-treated patients, suggesting that long-term patients only gained 0.1 kg more than those treated for 6 weeks. However, in placebo-treated patients the 6-week value increased from 0.3 to 0.9 kg/year [39].

Mean changes in heart rate and other electrocardiographic findings were generally small and not clinically meaningful [82]. Cariprazine did not show hERG inhibitory activity in vitro at concentrations well above therapeutic concentrations. In a clinical study evaluating QT prolongation, no QT prolongation was observed even at supratherapeutic doses (9 and 18 mg/day, respectively). Only a few cases of not severe QT prolongation have been reported in clinical trials [82]. In a pooled analysis of eight cariprazine clinical studies (i.e., four short-term, two open-label safety, one relapse prevention, one negative symptom), the incidence of potentially clinically significant QT prolongation measured by the Fridericia formula (QTcF > 500 ms or QTcF increase > 60 ms), a better predictor of severe cardiac consequences than the Bazett formula (QTcB) [84], was low in both treatment groups (cariprazine = 0.2%; placebo = 0.3%). Taking a conservative approach and looking at both the QTcF and QTcB, QT prolongation was observed in 0.9% of cariprazine patients versus 1.2% of placebo patients [85]. Further, in the open-label phase of the long-term relapse prevention study, more than 60 ms increase from baseline in QT prolongation was observed in 12 patients (1.6%) using QTcB and in 4 patients (0.5%) using QTcF; during the double-blind treatment period, more than 60 ms increase from baseline in QTcB was observed in three cariprazine-treated patients (3.1%) and two placebo-treated patients (2%) [39].

Cariprazine was not associated with hyperprolactinemia; on the contrary, high or high-normal baseline prolactin levels decreased to reference range values for cariprazine (− 12.9 ng/ml) and placebo (− 8.2 ng/ml) [86]. Further, sexual dysfunction TEAEs occurred in only a slightly higher percentage of cariprazine-treated patients (1.0%) than placebo-treated patients (0.3%), with higher rates noted in the active controls risperidone (2.7%) and aripiprazole (2%) [80, 87]. The most common sexual dysfunction TEAEs for cariprazine 3–6 mg/day were erectile dysfunction (0.4%), decreased libido (0.3%), amenorrhea (0.2%), and female orgasmic disorder (0.2%).

Discussion

Dopamine receptor partial agonists, such as cariprazine, are different than all other second-generation antipsychotics because of partial agonism at the dopamine D2 and D3 receptors; given their generally favorable tolerability profiles, these agents are considered first-line options for the treatment of schizophrenia [88]. The unique mechanism of action of cariprazine, a partial agonist with the highest affinity for the dopamine D3 receptor and longest half-life, supports broad-spectrum efficacy across the symptom domains of schizophrenia [22]. High dopamine D2 receptor affinity accounts for efficacy in reducing positive symptoms and preventing relapse of schizophrenia during long-term therapy. Greater affinity for D3 receptors than for D2 receptors and high in vivo occupancy at both D3 and D2 receptors are thought to promote efficacy against difficult to treat predominant and persistent negative symptoms and cognitive symptoms [24]. When results from a cariprazine proof-of-concept study revealed an efficacy signal for cariprazine in the treatment of acute exacerbation of schizophrenia, further exploration of its potential for efficacy was undertaken [41].

Short-term efficacy in schizophrenia was established in three phase 2/3 short-term clinical studies in which significant improvements in PANSS total score and CGI-S scores were demonstrated for all cariprazine doses versus placebo, with a clear dose–response relationship noted in each study. Further, efficacy across diverse symptoms and symptom domains was demonstrated in post hoc analyses of data from these positive pivotal studies, with significant advantages observed for cariprazine versus placebo in patients with baseline hostility, moderate/severe negative symptoms, and cognitive symptoms. Although antipsychotics are the gold standard of treatment for acute schizophrenia, there is no clear understanding of the relative risks and benefits that should guide clinical decision-making regarding which agent to use. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis by Huhn and colleagues explored the efficacy and tolerability of 32 antipsychotic medications in an attempt to compare and rank them according to information from randomized clinical trials [89]. In terms of efficacy, cariprazine was found to be more effective than many other antipsychotics against negative and depressive symptoms; cariprazine was further shown to be effective and better than placebo on positive symptoms, although it did not lead in this symptom category. In terms of side effects, cariprazine was better than many other agents on weight gain, prolactin elevation, QTc prolongation, and sedation. The authors concluded that while there are some efficacy differences between antipsychotics, most of them are gradual rather than discrete, while differences in side effects are more marked.

Although predominant positive symptoms may be the focus of clinical attention during an acute exacerbation of schizophrenia, addressing negative symptoms and cognitive symptoms is additionally important [90]. Across a spectrum of presenting symptom scenarios, cariprazine is considered a drug of choice for treating patients with schizophrenia and acute positive symptoms, first episode psychosis, predominant negative symptoms, and metabolic syndrome [90]. Once acute symptoms are stabilized, long-term treatment of schizophrenia is required to ensure symptom control and prevent relapse [91]. Importantly, long-term efficacy for cariprazine has been demonstrated in a relapse prevention trial where patients with stable symptoms who were randomized to cariprazine had a significantly longer time to relapse and significantly lower relapse rates than patients who were randomized to placebo. Post hoc analyses have further shown a significant advantage for cariprazine in sustaining relapse, with evidence suggesting that delayed relapse for cariprazine-treated patients may be associated with its longer half-life. Namely, in a comparison of similarly designed relapse prevention studies, the relapse rate at week 4 for patients randomized to placebo was lower for patients stabilized on cariprazine (5%) than for patients stabilized on other antipsychotics with shorter half-lives (8% to 34%), suggesting that the longer half-life of cariprazine and its active metabolites may have delayed relapse following the last dose of active treatment [60].

Finally, long-term efficacy for cariprazine versus the active comparator risperidone has been shown in patients with persistent and predominant negative symptoms of schizophrenia, a domain with few proven treatments and considerable unmet need. As such, patients with negative symptoms are considered a target treatment group for cariprazine owing to its clinical and pharmacological advantages over other antipsychotics in terms of negative symptom efficacy [90]. In fact, in an attempt to provide an algorithm for negative symptom treatment, Cerveri et al. have proposed cariprazine as first-line treatment for this patient population, followed by amisulpride, quetiapine, and olanzapine [52]. Additionally, since functional outcome is considered a therapeutic priority and an important component of well-being and quality of life in patients in schizophrenia [92], it is important to note that cariprazine-treated patients in the relapse prevention and negative symptom trials also had clinically relevant functional improvement as demonstrated by PSP total and subdomain scores.

The efficacy of a pharmacologic agent cannot be reviewed independently of its safety profile since poor tolerability and adverse effects may lead to partial adherence or medication discontinuation [93]. In clinical trials, cariprazine 1.5–12 mg/day was safe and generally well tolerated in patients with schizophrenia; akathisia, insomnia, and headache were among the most commonly reported cariprazine-related TEAEs, with a greater incidence of headache actually noted for placebo-treated patients than for cariprazine-treated patients. Although most TEAEs were considered mild or moderate in severity and rates of associated study discontinuation were low, it was noted that doses above 6 mg/day were more likely to be associated with certain AEs (e.g., akathisia, blood pressure changes, weight gain) [78]. In consideration of comparable efficacy and better tolerability at the lower end of the dose range, the FDA and EMA established a 1.5–6 mg/day recommended dose range for cariprazine in the treatment of schizophrenia [39, 94], with additional analyses conducted in this dose range supporting the previously established safety profile. Across studies and post hoc analyses, cariprazine has been shown to be safe and generally well tolerated in patients with schizophrenia, with a neutral metabolic profile, clinically nonsignificant cardiac changes, no prolactin level increase, and small body weight increases. For these reasons, cariprazine is judged to be an advantageous treatment option for patients with schizophrenia and, although treatment decisions need to be made with individual patient characteristics in mind, cariprazine is among the safest antipsychotic treatment options available [90, 95]. In most cases, cariprazine-related AEs can be successfully managed by dose reduction; akathisia may be managed by lower doses or a combination of dose reduction and rescue medication [90].

This is a narrative review that has some inherent limitations related to the studies and analyses that were selected for inclusion. Given the volume of available cariprazine information, not every cariprazine study or analysis could be included in this review; studies were included on the basis of the authors’ expert judgment. Active comparators used for assay sensitivity were not included in every short-term cariprazine study; further, studies that included an active comparator were not powered to detect differences between cariprazine and the active comparator. Although negative symptom scales (e.g., Brief Negative Symptom Scale, Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms) may have some advantages for assessing negative symptom dimension constructs, the PANSS negative symptom subscale is also considered a reliable and valid measure in clinical trials, with the use of analysis-derived negative factors preferred to the full subscale [96]. In the cariprazine studies, negative symptoms were assessed by change from baseline in PANSS-FSNS, a PANSS-derived scale that is also referred to as the Marder factor for negative symptoms. Although the PANSS is not a negative symptom-specific scale, the PANSS-FSNS has been shown to adequately measure clinical changes in a negative symptom population [97]. Namely, linking results demonstrated that greater improvement on PANSS-FSNS corresponded to clinical impressions of greater improvement, as measured by the Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement Scale (CGI-I), and less severe disease states, as measured by the CGI-S. Finally, some of the long-term studies were open-label and no active or placebo comparators were used.

Antipsychotic medication has been the foundation of effective schizophrenia treatment for several decades. Although all agents rely on dopamine D2 receptor blockade for antipsychotic efficacy, cariprazine is additionally associated with a unique pharmacology that supports well-defined efficacy advantages, and a good safety and tolerability profile. In short- and long-term clinical trials, as well as in numerous post hoc investigations, cariprazine has demonstrated broad-spectrum efficacy across the diverse domains of schizophrenia, thereby establishing its place as a valuable therapeutic solution for the treatment of schizophrenia in daily clinical practice.

References

Perälä J, Suvisaari J, Saarni SI, et al. Lifetime prevalence of psychotic and bipolar I disorders in a general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(1):19–28.

Kanchanatawan B, Thika S, Anderson G, Galecki P, Maes M. Affective symptoms in schizophrenia are strongly associated with neurocognitive deficits indicating disorders in executive functions, visual memory, attention and social cognition. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;80(Pt C):168–76.

Owen MJ, Sawa A, Mortensen PB. Schizophrenia. Lancet. 2016;388(10039):86–97.

Haddad PM, Correll CU. The acute efficacy of antipsychotics in schizophrenia: a review of recent meta-analyses. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2018;8(11):303–18.

Insel TR. Rethinking schizophrenia. Nature. 2010;468(7321):187–93.

Hunter R, Barry S. Negative symptoms and psychosocial functioning in schizophrenia: neglected but important targets for treatment. Eur Psychiatry. 2012;27(6):432–6.

Rabinowitz J, Berardo CG, Bugarski-Kirola D, Marder S. Association of prominent positive and prominent negative symptoms and functional health, well-being, healthcare-related quality of life and family burden: a CATIE analysis. Schizophr Res. 2013;150(2–3):339–42.

Suttajit S, Pilakanta S. Predictors of quality of life among individuals with schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:1371–9.

Solmi M, Murru A, Pacchiarotti I, et al. Safety, tolerability, and risks associated with first- and second-generation antipsychotics: a state-of-the-art clinical review. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2017;13:757–77.

Farah A. Atypicality of atypical antipsychotics. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;7(6):268–74.

Correll CU. From receptor pharmacology to improved outcomes: individualising the selection, dosing, and switching of antipsychotics. Eur Psychiatry. 2010;25(Suppl 2):S12-21.

Shayegan DK, Stahl SM. Atypical antipsychotics: matching receptor profile to individual patient’s clinical profile. CNS Spectr. 2004;9(10 Suppl 11):6–14.

Leucht S, Corves C, Arbter D, et al. Second-generation versus first-generation antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373(9657):31–41.

Chow CL, Kadouh NK, Bostwick JR, VandenBerg AM. Akathisia and newer second-generation antipsychotic drugs: a review of current evidence. Pharmacotherapy. 2020;40(6):565–74.

Rauly-Lestienne I, Boutet-Robinet E, Ailhaud MC, Newman-Tancredi A, Cussac D. Differential profile of typical, atypical and third generation antipsychotics at human 5-HT7a receptors coupled to adenylyl cyclase: detection of agonist and inverse agonist properties. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2007;376(1–2):93–105.

Lieberman JA. Dopamine partial agonists: a new class of antipsychotic. CNS Drugs. 2004;18(4):251–67.

Casey AB, Canal CE. Classics in chemical neuroscience: aripiprazole. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2017;8(6):1135–46.

Kiss B, Horváth A, Némethy Z, et al. Cariprazine (RGH-188), a dopamine D(3) receptor-preferring, D(3)/D(2) dopamine receptor antagonist-partial agonist antipsychotic candidate: in vitro and neurochemical profile. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;333(1):328–40.

Sokoloff P, Giros B, Martres MP, Bouthenet ML, Schwartz JC. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel dopamine receptor (D3) as a target for neuroleptics. Nature. 1990;347(6289):146–51.

Sokoloff P, Le Foll B. The dopamine D3 receptor, a quarter century later. Eur J Neurosci. 2017;45(1):2–19.

Ágai-Csongor É, Domány G, Nógrádi K, et al. Discovery of cariprazine (RGH-188): a novel antipsychotic acting on dopamine D3/D2 receptors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22(10):3437–40.

Calabrese F, Tarazi FI, Racagni G, Riva MA. The role of dopamine D3 receptors in the mechanism of action of cariprazine. CNS Spectr. 2020;25(3):343–51.

Stahl SM. Mechanism of action of cariprazine. CNS Spectr. 2016;21(2):123–7.

Girgis RR, Slifstein M, D’Souza D, et al. Preferential binding to dopamine D3 over D2 receptors by cariprazine in patients with schizophrenia using PET with the D3/D2 receptor ligand [(11)C]-(+)-PHNO. Psychopharmacology. 2016;233(19–20):3503–12.

Gyertyán I, Kiss B, Sághy K, et al. Cariprazine (RGH-188), a potent D3/D2 dopamine receptor partial agonist, binds to dopamine D3 receptors in vivo and shows antipsychotic-like and procognitive effects in rodents. Neurochem Int. 2011;59(6):925–35.

Duric V, Banasr M, Franklin T, et al. Cariprazine exhibits anxiolytic and dopamine D3 receptor-dependent antidepressant effects in the chronic stress model. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;20(10):788–96.

Zimnisky R, Chang G, Gyertyán I, et al. Cariprazine, a dopamine D(3)-receptor-preferring partial agonist, blocks phencyclidine-induced impairments of working memory, attention set-shifting, and recognition memory in the mouse. Psychopharmacology. 2013;226(1):91–100.

Laszlovszky I, Gage A, Kapas M, Ghahramani P. Characterization of cariprazine (RGH-188) D3/D2 receptor occupancy in healthy volunteers and schizophrenic patients by positron emission tomography (PET). Eur Psychiatry. 2010;25(S1):1.

Girgis R, Abi-Dargham A, Slifstein M, et al. In vivo dopamine D3 and D2 receptor occupancy profile of cariprazine versus aripiprazole: a PET study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42:S595.

Girgis RR, Forbes A, Abi-Dargham A, Slifstein M. A positron emission tomography occupancy study of brexpiprazole at dopamine D2 and D3 and serotonin 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors, and serotonin reuptake transporters in subjects with schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020;45(5):786–92.

Mizrahi R, Agid O, Borlido C, et al. Effects of antipsychotics on D3 receptors: a clinical PET study in first episode antipsychotic naive patients with schizophrenia using [11C]-(+)-PHNO. Schizophr Res. 2011;131(1–3):63–8.

Gyertyán I, Sághy K, Laszy J, et al. Subnanomolar dopamine D3 receptor antagonism coupled to moderate D2 affinity results in favourable antipsychotic-like activity in rodent models: II behavioural characterisation of RG-15. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2008;378(5):529–39.

Joyce JN, Millan MJ. Dopamine D3 receptor antagonists as therapeutic agents. Drug Discov Today. 2005;10(13):917–25.

Kiss B, Laszlovszky I, Horváth A, et al. Subnanomolar dopamine D3 receptor antagonism coupled to moderate D2 affinity results in favourable antipsychotic-like activity in rodent models: I neurochemical characterisation of RG-15. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2008;378(5):515–28.

Laszy J, Laszlovszky I, Gyertyán I. Dopamine D3 receptor antagonists improve the learning performance in memory-impaired rats. Psychopharmacology. 2005;179(3):567–75.

Leggio GM, Salomone S, Bucolo C, et al. Dopamine D(3) receptor as a new pharmacological target for the treatment of depression. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013;719(1–3):25–33.

Kiss B, Némethy Z, Fazekas K, et al. Preclinical pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic characterization of the major metabolites of cariprazine. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2019;13:3229–48.

Nakamura T, Kubota T, Iwakaji A, et al. Clinical pharmacology study of cariprazine (MP-214) in patients with schizophrenia (12-week treatment). Drug Des Devel Ther. 2016;10:327–38.

Reagila SPC. Reagila [Summary of Product Characteristics]. Update 06/25/2018. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/reagila-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed 4 May 2021

Durgam S, Cutler AJ, Lu K, et al. Cariprazine in acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: a fixed-dose, phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(12):e1574–82.

Durgam S, Litman RE, Papadakis K, et al. Cariprazine in the treatment of schizophrenia: a proof-of-concept trial. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;31(2):61–8.

Durgam S, Starace A, Li D, et al. An evaluation of the safety and efficacy of cariprazine in patients with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: a phase II, randomized clinical trial. Schizophr Res. 2014;152(2–3):450–7.

Kane JM, Zukin S, Wang Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of cariprazine in acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: Results from an international, phase III clinical trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;35(4):367–73.

Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261–76.

Guy W. The Clinical Global Impression Severity and Improvement Scales. ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology. US Department of Health, Education and Welfare publication (ADM). 76–338. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health; 1976:218–222.

Durgam S, Earley W, Li R, et al. Long-term cariprazine treatment for the prevention of relapse in patients with schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Schizophr Res. 2016;176(2–3):264–71.

Arango C, Garibaldi G, Marder SR. Pharmacological approaches to treating negative symptoms: a review of clinical trials. Schizophr Res. 2013;150(2–3):346–52.

Buchanan RW. Persistent negative symptoms in schizophrenia: an overview. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33(4):1013–22.

Németh G, Laszlovszky I, Czobor P, et al. Cariprazine versus risperidone monotherapy for treatment of predominant negative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia: a randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10074):1103–13.

Marder SR, Davis JM, Chouinard G. The effects of risperidone on the five dimensions of schizophrenia derived by factor analysis: combined results of the North American trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(12):538–46.

Nasrallah H, Morosini P, Gagnon DD. Reliability, validity and ability to detect change of the Personal and Social Performance scale in patients with stable schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2008;161(2):213–24.

Cerveri G, Gesi C, Mencacci C. Pharmacological treatment of negative symptoms in schizophrenia: update and proposal of a clinical algorithm. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:1525–35.

Marder S, Fleischhacker WW, Earley W, et al. Efficacy of cariprazine across symptom domains in patients with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: pooled analyses from 3 phase II/III studies. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019;29(1):127–36.

Volavka J, Czobor P, Derks EM, et al. Efficacy of antipsychotic drugs against hostility in the European First-Episode Schizophrenia Trial (EUFEST). J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(7):955–61.

Citrome L, Durgam S, Lu K, Ferguson P, Laszlovszky I. The effect of cariprazine on hostility associated with schizophrenia: post hoc analyses from 3 randomized controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(1):109–15.

Busner J, Targum SD. The clinical global impressions scale: applying a research tool in clinical practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2007;4(7):28–37.

Durgam S, Earley W, Lu K, et al. Global improvement with cariprazine in the treatment of bipolar I disorder and schizophrenia: a pooled post hoc analysis. Int J Clin Pract. 2017;71(12):e13037.

Kane JM, Kishimoto T, Correll CU. Non-adherence to medication in patients with psychotic disorders: epidemiology, contributing factors and management strategies. World Psychiatry. 2013;12(3):216–26.

Correll CU, Potkin SG, Zhong Y, et al. Long-term remission with cariprazine treatment in patients with schizophrenia: a post hoc analysis of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, relapse prevention trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(2):1.

Correll CU, Jain R, Meyer JM, et al. Relationship between the timing of relapse and plasma drug levels following discontinuation of cariprazine treatment in patients with schizophrenia: indirect comparison with other second-generation antipsychotics after treatment discontinuation. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:2537–50.

Earley W, Guo H, Daniel D, et al. Efficacy of cariprazine on negative symptoms in patients with acute schizophrenia: a post hoc analysis of pooled data. Schizophr Res. 2019;204:282–8.

Fleischhacker W, Galderisi S, Laszlovszky I, et al. The efficacy of cariprazine in negative symptoms of schizophrenia: post hoc analyses of PANSS individual items and PANSS-derived factors. Eur Psychiatry. 2019;58:1–9.

Laszlovszky I, Kiss B, Barabássy Á, et al. Cognitive improving properties of cariprazine, a dopamine D3 receptor preferring partial agonist: overview of non-clinical and clinical data. Eur Psychiatry. 2019;56(Suppl):S238.

Cutler AJ, Durgam S, Wang Y, et al. Evaluation of the long-term safety and tolerability of cariprazine in patients with schizophrenia: results from a 1-year open-label study. CNS Spectr. 2018;23(1):39–50.

Durgam S, Greenberg WM, Li D, et al. Safety and tolerability of cariprazine in the long-term treatment of schizophrenia: results from a 48-week, single-arm, open-label extension study. Psychopharmacology. 2017;234(2):199–209.

McEvoy J, Earley W, Guo H, Szatmári B, Hostetler C. Long-term effects of cariprazine in patients with negative symptoms of schizophrenia: a post hoc analysis of two 48-week, open-label studies. Poster presented at the 171st Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; New York, NY; May 5–9; 2018.

Gkintoni E, Pallis EG, Bitsios P, Giakoumaki SG. Neurocognitive performance, psychopathology and social functioning in individuals at high risk for schizophrenia or psychotic bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2017;208:512–20.

Kuswanto C, Chin R, Sum MY, et al. Shared and divergent neurocognitive impairments in adult patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: Whither the evidence? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;61:66–89.

Fleischhacker WW, Marder S, Lu K, et al. Efficacy of cariprazine versus placebo across schizophrenia symptom domains: pooled analyses from 3 phase II/III trials. Poster presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology; Miami, Florida; June 22–25, 2015

Simpson PM, Surmon DJ, Wesnes KA, Wilcock GK. The cognitive drug research computerized assessment system for demented patients: a validation study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1991;6(2):95–102.

Bobes J, Garcia-Portilla MP, Bascaran MT, Saiz PA, Bousono M. Quality of life in schizophrenic patients. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2007;9(2):215–26.

Martin CR, Allan R. Factor structure of the schizophrenia quality of life scale revision 4 (SQLS-R4). Psychol Health Med. 2007;12(2):126–34.

Kahn R, Earley W, Kaifeng L, et al. Effects of cariprazine on health-related quality of life in patients with schizophrenia. Poster presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; Toronto, Ontario, Canada; May 16–20, 2015.

Cutler AJ, Durgam S, Lu K, Laszlovszky I, Earley W. Post hoc analysis of a randomized, controlled trial. Poster presented at the 169th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; Atlanta, Georgia; May 14–18, 2016

Laszlovszky I, Acsai K, Barabássy Á, et al. Long-term functional improving effects of cariprazine: Post-hoc analyses of acute and predominant negative symptom schizophrenia patient data. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020;40(Suppl 1):S326–7.

Mofsen RS, Xu S, Németh G, et al. Efficacy of cariprazine by baseline symptom severity in patients with schizophrenia: A post hoc analysis of 3 randomized controlled trials. Poster presented at the 170th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; San Diego, CA; May 20–24, 2017

Mofsen R, Chang C-T, Németh G, Barabássy Á, Earley W. Efficacy of cariprazine in patients with schizophrenia based on stage of illness. Presented at the Biennial International Congress on Schizophrenia Research; San Diego, California, March 24–28, 2017

Earley W, Durgam S, Lu K, et al. Safety and tolerability of cariprazine in patients with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: a pooled analysis of four phase II/III randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017;32(6):319–28.

Nasrallah HA, Earley W, Cutler AJ, et al. The safety and tolerability of cariprazine in long-term treatment of schizophrenia: a post hoc pooled analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):305.

Barabássy Á, Sebe B, Acsai K, et al. Safety and tolerability of cariprazine in patients with schizophrenia: a pooled analysis of eight phase II/III studies. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2021;17:957–70.

Barabássy Á, Sebe B, Szatmári B, et al. Akathisia during cariprazine treatment: post-hoc analyses of pooled schizophrenia studies. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019;29(Suppl 6):S323.

European Medicines Agency. Assessment Report. Reagila. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Public_assessment_report/human/002770/WC500234926.pdf. Accessed 11 Mar 2021.

Sebe B, Barabássy Á, Szatmári B, et al. Short- and long-term changes in metabolic parameters and body weight in cariprazine-treated patients with schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2019;56(1):S824.

Vandenberk B, Vandael E, Robyns T, et al. Which QT correction formulae to use for QT monitoring. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(6):e003264.

Barabassy Á, Sebe B, Laszlovszky I, et al. Cardiac safety with cariprazine treatment. Eur Psychiatry. 2020;63(S1):S252–3.

Szatmári B, Barabássy Á, Laszlovszky I, et al. Safety profile of cariprazine: post hoc analysis of safety parameters of pooled cariprazine schizophrenia studies. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018;29(Suppl 1):S419.

Barabássy Á, Szatmári B, Laszlovszky I, et al. Hormonal effects of cariprazine: post hoc analysis of pooled data from schizophrenia studies for sexual dysfunction and prolactin changes. Eur Psychiatry. 2018;48(Suppl):S701.

Keks N, Hope J, Schwartz D, et al. Comparative tolerability of dopamine D2/3 receptor partial agonists for schizophrenia. CNS Drugs. 2020;34(5):473–507.

Huhn M, Nikolakopoulou A, Schneider-Thoma J, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 32 oral antipsychotics for the acute treatment of adults with multi-episode schizophrenia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2019;394(10202):939–51.