Abstract

Obesity is one of the main risk factors for type 2 diabetes (T2D), representing a major worldwide health crisis. Modest weight-loss (≥ 5% but < 10%) can minimize and reduce diabetes-associated complications, and significant weight-loss can potentially resolve disease. Treatment guidelines recommend that intensive lifestyle interventions, pharmacologic therapy, and/or metabolic surgery be considered as options for patients with T2D and obesity. The benefits and risks of such interventions should be evaluated in the context of their weight-loss potential, ability to sustain weight change, side effect profile, and costs. Antihyperglycemia therapies have considerable effects on patient weight, prompting careful consideration of weight-loss or weight-neutral therapies for patients with T2D who also have obesity. Metformin, sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs), α-glucosidase inhibitors, and amylin mimetics promote weight-loss. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors and fixed-ratio insulin/GLP-1 RA combination therapies (IDegLira, iGlarLixi) appear to be weight-neutral. Thiazolidinediones, insulin secretagogues (sulfonylureas, meglitinides), and insulins are associated with weight gain. Sulfonylureas are additionally associated with a higher risk of serious hypoglycemia from hyperinsulinemia, making them less suitable for the treatment of patients who are overweight or have obesity. Patients are often overtitrated on basal insulin, resulting in an increased risk of hypoglycemia and weight gain without achieving glycemic goals. Given these observations, the effects of antihyperglycemia agents on weight should be considered when individualizing T2D therapy.

Funding: Sanofi US, Inc.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The increasing prevalence of both obesity and type 2 diabetes (T2D) represents major public health crises worldwide. Obesity increases the risk of multiple diseases, and is believed to account for 80 − 85% of the risk for developing T2D [1]. In 2015, diabetes affected around 30 million people in the USA alone (9.4% of the population), of which 90 − 95% of cases were type 2 [2]. As expected, given its relationship to disease risk, a high proportion of people diagnosed with diabetes in the US are overweight [body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 kg/m2] or have obesity (87.5%; BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) [2].

For patients with T2D, prevention of weight gain, and modest weight reduction of as little as 5%, can reduce diabetes-associated complications and significantly improve cardiovascular risk factors [3, 4]. However, weight gain during antidiabetes therapy is common and has been cited as a reason for delaying treatment intensification—particularly with insulin-based regimens [5]. A combination of clinician perceptions and attitudes, patient concerns about weight gain and potential hypoglycemia, and the increasing complexity of treatment options contribute to reluctance in therapy escalation, leading to clinical inertia [5,6,7]. Overcoming clinical inertia is paramount in the effective treatment of diabetes, and communication between clinicians and patients about antihyperglycemia therapies may help dispel some of the concerns associated with treatment progression [7]. Given that the benefits and detriments may be prioritized differently by patients and their clinicians (for example, a change in body weight might present a significant concern to a patient, but be considered a normal part of therapy to the clinician), it is important that clinicians consider not only the antihyperglycemia effects of selected medications, but also the effect they may have on body weight.

This review presents an overview of the relationship between T2D and obesity, and discusses the effects of widely used classes of antihyperglycemia agents on body weight. The information in this article is based on previously conducted studies and does not include any new report of findings not previously published by any of the authors.

Relationship Between Obesity and T2D

While the underlying cause of T2D is multifactorial, the cardinal features are a decline in insulin production by pancreatic β-cells and peripheral insulin resistance [8]. A number of factors play a major role in the development of both obesity and T2D (Fig. 1), and studies have identified a wide range of potential links between the two conditions relating to insulin resistance, pro-inflammatory cytokines, endothelial dysfunction, deranged fatty acid metabolism, and cellular processes such as mitochondrial dysfunction and endoplasmic reticulum stress [3, 9, 10].

Reproduced with permission from Scheen AJ, Van Gaal LF. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2:911–922. [3] © 2014 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved

Complex pathophysiology of obesity and type 2 diabetes. GIP glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (gastric inhibitor polypeptide), GLP-1 RA glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist, NEFA non-esterified fatty acids

Excess adiposity and fat distribution have a strong relationship with hyperinsulinemia and T2D; fat distribution may be equally, or more, important than adiposity in determining development of T2D [11]. Increased upper body fat—visceral fat in particular—is associated with metabolic syndrome, T2D, and cardiovascular disease. Though the mechanism behind this has not been fully elucidated, it is likely to be related to differences in functional subtypes of adipose tissue. Overall, visceral fat is more metabolically active than subcutaneous fat, producing a range of adipose-specific cytokines (such as adiponectin) as well as pro-inflammatory cytokines that contribute to metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance [9, 12].

Strategies Used for Weight-Loss in T2D

The primary clinical goals of weight-loss in patients with T2D are achievement of glycemic targets, improvement of lipid profile, and normalization of blood pressure [13]. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends a glycated hemoglobin A1c (A1C) target of < 7.0% for most adults with T2D. However, these goals must be individualized for each patient according to their needs. More stringent A1C goals (such as target A1C < 6.5%) may be suitable for younger patients, or for patients with a short duration of diabetes, provided they are achieved without significant hypoglycemia or significant adverse events. Conversely, less stringent A1C goals (such as target A1C < 8.0%) may be suitable for older patients, or those patients with extensive comorbidities, high risk of hypoglycemia, or a long duration of diabetes. “Over-basalization” (a commonly used term amongst health care providers when referring to detrimentally high amounts of basal insulin [14]) can occur when the basal insulin dose is increased but A1C remains uncontrolled due to a lack of postprandial glucose control. Over-basalization is associated with increased weight gain and hypoglycemia risk [14] and is an important consideration for weight-loss strategies in patients using basal insulin to manage their T2D.

Sustained weight-loss (≥ 5% after one year) has been shown to improve glycemic control in patients with obesity [8, 15, 16]. In addition, there is strong and consistent evidence that modest, sustained weight-loss can delay the progression from prediabetes to T2D [16]. Recent treatment guidelines from the ADA and The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) and American College of Endocrinology (ACE) recommend weight-loss through lifestyle modification or nonsurgical energy restriction promoting weight-loss with the goal of reducing body weight by 5–10% in patients with T2D and a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 [8, 13]. The use of weight-loss medication is recommended as an option for eligible patients with a BMI ≥ 27 kg/m2 [8, 13]. Recommendations for bariatric surgery differ between guidelines, with AACE recommending it as an option for patients with a BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2, and ADA recommending it for patients with a BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2 (≥ 37.5 kg/m2 in Asian Americans) [8, 13].

Nutrition education at diagnosis and throughout the care process is advocated by the ADA and the AACE/ACE to support lifestyle modification and achieve weight-loss [8, 13, 17], and is an annually renewable benefit in insurance plans in the US [18, 19]. ADA guidelines state that lifestyle intervention programs should be intensive and involve frequent follow-ups [8]. Despite these recommendations, data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) indicate that only 54.6% of patients reported receiving any diabetes education, and in a study investigating the effects of diabetes and nutrition education on health outcomes, only 13.4% had received an educational visit of any kind [20, 21]. Clinical data indicate that lifestyle interventions can achieve long-term results overall, despite the tendency for patients to regain weight over time [22]. In the Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) trial of intensive lifestyle interventions, a 6% decrease in body weight was achieved after 9.6 years of follow-up [23]. Participants also showed improved glucose control over the follow-up period [23, 24].

The National Institutes of Health obesity guidelines suggest the use of weight-management medications as an adjunct to lifestyle modifications in patients with a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 (or ≥ 27 kg/m2 in patients with concomitant risk factors and/or diseases); however, insurance coverage and patient selection criteria for weight-loss medication have been prohibitive and a barrier to therapy options [8, 25]. Five agents (or combinations) are currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for long-term weight management in patients with T2D: orlistat (a lipase inhibitor); lorcaserin (a selective serotonin receptor agonist); phentermine/topiramate (a sympathomimetic amine anorectic in combination with an antiepileptic); naltrexone/bupropion (an opioid antagonist in combination with an aminoketone antidepressant); and liraglutide at a dose of 3 mg (a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist [GLP-1 RA]) [8]. Data from clinical trials show average one-year weight-losses with these agents; the percentage of subjects losing sufficient body weight (≥ 5%) was 35–73% with orlistat, 38–48% with lorcaserin, 45–70% with phentermine/topiramate, 36–57% with naltrexone/bupropion, and 51–73% with liraglutide [8, 26,27,28,29,30,31,32].

The ADA recommends metabolic/bariatric surgery as a treatment option for T2D in eligible patients with a BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2 (≥ 37.5 kg/m2 in Asian Americans) regardless of the extent of glycemic control and in patients with a BMI 30.0–34.9 kg/m2 (27.5–32.4 kg/m2 in Asian Americans) with inadequately controlled hyperglycemia despite optimal medical therapy [8]. The effects of bariatric surgery on T2D are profound and may include temporary disease remission. In a large meta-analysis (N = 135,246), patients with T2D and severe obesity who underwent bariatric surgery achieved a 58% reduction in excess body weight, and 78% of patients no longer showed clinical manifestations of T2D after two years. The overall A1C reduction was 2.1% [33].

Addressing excess weight can have a significant impact on outcomes in diabetes care. Lifestyle, pharmacologic, and surgical interventions all have the potential to reduce weight sufficiently to improve glycemic control, and each is associated with its own risks and benefits [8, 13]. Discussion regarding the pros and cons of each strategy should be an integral part of managing T2D in overweight patients.

Effects of Antihyperglycemia Drugs on Body Weight

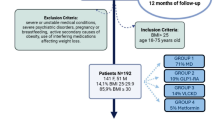

The effects of antihyperglycemia therapy on clinical outcomes (including body weight) vary both between and within the drug classes (Fig. 2) [13]. The ADA recommends choosing glucose-lowering medications that are weight-neutral or that promote weight-loss when treating patients with T2D who are overweight or have obesity with a hierarchy of choice [8]. In the following section we will review the drug classes associated with weight-loss, as well as those that are weight-neutral, and those that are associated with weight gain. In addition to the effects on weight, potential adverse events and dosing schedules also impact patients on a daily basis, and should be considered when individualizing therapy (Table 1).

Reprinted with permission from American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists © 2018 AACE. Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI, et al. AACE/ACE comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm 2018. Endocr Pract. 2018;24:91–120

Profiles of antidiabetic medications. AGI alpha-glucosidase inhibitor, ASCVD atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, BCR-QR bromocriptine qui release, CHF congestive heart failure, COLSVL colesevelam, DPP-4i dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitor, FDA US Food and Drug Administration, GI Sx gastrointestinal side effects, GLN glinides, GLP-1 RA glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist, MET metformin, PRAML pramlintide, SGLT-2i sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor, SU sulfonylurea, TZD thiazolidinedione

Drug Classes Associated with Weight-Loss

Metformin

Metformin is the first-line recommended treatment for T2D. It has a low risk of hypoglycemia and promotes slight weight-loss and euglycemia with only mild gastrointestinal side effects [8, 13, 34]. Metformin has been shown to reduce A1C levels by ~ 1% compared with placebo [35]. Approximately 50% of the studies conducted in drug-naïve patients to date have shown significant reductions in body weight with metformin relative to baseline or comparators, and weight changes of + 1.5 to − 2.9 kg in insulin-naïve patients have been reported [36]. The mechanisms behind weight-loss with metformin are not fully understood, but are likely related, at least in part, to its anorectic effects [37].

α-Glucosidase Inhibitors

α-Glucosidase inhibitors delay the absorption of carbohydrates in the gastrointestinal tract, which subsequently slows the spike in postprandial glucose. They demonstrate A1C-lowering effects (reductions of ~ 1% versus placebo) and a low risk of hypoglycemia; they demonstrate cardiovascular benefit in patients with impaired glucose tolerance and T2D, and are associated with weight-loss [8, 13, 35]. Weight change associated with α-glucosidase inhibitors ranges from − 0.43 to − 1.80 kg [38,39,40,41]. α-Glucosidase inhibitors may also cause dose-related gastrointestinal side effects, such as flatulence and diarrhea [42].

Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists (GLP-1 RAs)

GLP-1 RAs reduce postprandial glucose levels by a variety of mechanisms. They activate GLP-1 receptors in the pancreas to stimulate insulin secretion and suppress glucagon secretion [43, 44]. They also act on GLP-1 receptors in the central nervous system to decrease appetite. Further, they act on the gastrointestinal tract to slow gastric motility and emptying; this delays intestinal glucose absorption, which reduces postprandial glucose excursions and also leads to reduced appetite and enhanced satiety [43, 44]. These agents show efficacy in reducing A1C (reductions of ~ 0.8% to 1.9% compared with baseline), have a low risk of hypoglycemia due to their glucose-dependent mechanism of action, and are usually associated with reductions in weight and blood pressure [13, 45]. The most common side effects with GLP-1 RAs are transient, mild-to-moderate gastrointestinal adverse events (such as nausea and vomiting) [46, 47]. GLP-1 RAs are an injectable therapy, with injection requirements ranging from twice daily to once weekly, depending on the formulation. Clinical trial data show that GLP-1 RA therapy is associated with weight change ranging from − 1.14 to − 6.9 kg [38,39,40,41, 48, 49].

Amylin Mimetics

Pramlintide, which is indicated for patients who use meal-time insulin therapy and have failed to reach glycemic targets [50], has A1C-lowering effects (reductions of ~ 0.33% versus placebo), and is associated with gastrointestinal side effects, an increased risk of hypoglycemia with insulin therapy (unless insulin dose is decreased concomitantly), and the need for multiple daily injections [51, 52]. In clinical diabetes trials, pramlintide consistently and significantly lowered body weight compared with placebo (between-group differences of 1.5 to 2.5 kg; P < 0.01) [52]. Weight-loss efficacy is likely related to enhanced satiety and slowed gastric emptying, and studies have shown reduced food and caloric intake in non-diabetic individuals with obesity [52, 53]. In patients with obesity who do not have diabetes, significant reductions in weight (weighted mean difference − 2.27 kg) and waist circumference (weighted mean difference − 2.02 cm) have been achieved [51]). The effects of pramlintide on weight appear to be independent of gastrointestinal side effects [52].

Sodium Glucose Co-Transporter 2 (SGLT2) Inhibitors

SGLT2 inhibitors prevent glucose reabsorption in the proximal tubules of the kidneys, resulting in an increase in urinary glucose excretion [54, 55]. They have A1C-lowering efficacy (reductions of ~ 0.69% compared with placebo) with a low incidence of hypoglycemia, and are associated with weight-loss and systolic blood pressure reduction [8, 13, 54, 56]. Adverse events associated with SGLT2 inhibitors include increased urogenital infections and bone fractures [13, 54, 57,58,59].

Meta-analyses have revealed a greater loss of body weight in patients treated with SGLT2 inhibitors (− 0.9 to − 2.5 kg) compared with placebo and oral antidiabetes drugs including metformin, sulfonylureas, and dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors [54, 60]. weight-loss with SGLT2 inhibitors is associated with significant decreases in total body fat, waist circumference, index of central obesity, and visceral adiposity [57, 61]. The increased renal excretion of glucose is thought to induce weight-loss through both the induced calorie deficit and fluid loss resulting from increased osmotic diuresis [62].

Weight-Neutral Agents

Dipeptidyl Peptidase 4 (DPP-4) Inhibitors

DPP-4 inhibitors have A1C-lowering properties (reductions of ~ 0.75% versus placebo) with a low risk of hypoglycemia, are weight-neutral, and are well tolerated, with reported adverse event rates of hypersensitivity and skin-related reactions similar to placebo in pooled analyses [13, 35, 63]. The range of weight change associated with DPP-4 inhibitor therapy is − 0.09 to +1.11 kg [38, 40, 41, 48]. In patients already on metformin, the addition of a DPP-4 inhibitor resulted in a more favorable weight profile versus the addition of a sulfonylurea, meglitinide, or thiazolidinedione (TZD), but not versus the addition of a GLP-1 RA [40, 64].

Fixed-Ratio Combination Therapy

Once-daily GLP-1 RA/basal insulin titratable fixed-ratio combinations [insulin glargine and lixisenatide (iGlarLixi) and insulin degludec and liraglutide (IDegLira)] produce greater A1C reductions (~ 0.72%) compared with basal insulin alone, with a higher likelihood of achieving A1C < 7.0% than with using each individual agent on its own [65]. Fixed-ratio combination therapies also help to mitigate the weight gain associated with basal insulin use without increasing hypoglycemia risk, and have a significantly lower frequency of gastrointestinal adverse events compared with GLP-1 RAs alone, likely reflecting the gradual increase in GLP-1 RA dose that parallels titration of the basal insulin component [46, 66].

Clinical trial data from patients receiving fixed-ratio combination therapies showed a weight change of − 0.3 kg to − 0.7 kg for iGlarLixi and − 2.7 to + 2.0 for IDegLira [67,68,69,70,71]. These differences in weight are due to the use of either liraglutide or lixisenatide in the combination with insulin [71, 72].

The safety and efficacy profiles of fixed-ratio combinations, combined with their ease of use, decreased injection burden, and potential to address over-basalization, make them particularly useful in patients who are overweight or have obesity, or who wish to avoid weight gain, and those who require intensification of basal insulin therapy.

Drug Classes Associated with Weight Gain

Sulfonylureas

Sulfonylureas show high efficacy in lowering A1C (reductions of ~ 1.25% versus placebo), but are associated with weight gain and hypoglycemia [13, 35]. Sulfonylureas are considered to have the highest risk of severe hypoglycemia of the available T2D therapies [13]. Meta-analyses have demonstrated that when added to other agents, sulfonylureas are associated with weight gain ranging between 2.01 and 2.3 kg versus placebo [38, 40, 73]. Due to associated hypoglycemia, weight gain, and possible cardiovascular risk, together with their diminished efficacy over time, sulfonylureas should be avoided in patients with obesity [74].

Thiazolidinediones (TZDs)

TZDs show relatively high efficacy in reducing A1C (reductions of ~ 1.25% versus placebo), are associated with weight gain and a low risk of hypoglycemia, and induce durable antihyperglycemia effects [8, 13, 35]. Weight gain seen with TZDs ranges from 2.30 to 4.25 kg [38,39,40,41, 48], and is thought to be related to a number of mechanisms, including fluid retention and redistribution of adipose tissue [75].

Meglitinides (glinides)

Glinides have A1C-lowering properties (reductions of ~ 0.75% versus placebo), a shorter half-life, and a similar side effect profile, but with a lower risk of hypoglycemia, compared with sulfonylureas [13, 35, 74]. In addition, their relatively short half-life means they must be administered frequently [74]. Weight gain is similar to that seen with sulfonylureas (0.91 to 2.67 kg), which suggests glinides should also be avoided in patients with obesity [38, 40, 41].

Insulin and Insulin Analogs

Insulin remains the most effective glucose-lowering agent—especially in patients with elevated A1C. A significant proportion of patients with T2D require insulin therapy as their disease progresses because of β-cell failure. Compared with most other antihyperglycemia therapies, there is a substantial risk of hypoglycemia with insulin—especially with regimens that include prandial insulin [13]. Weight gain with insulin ranges between 1.56 and 5.75 kg, which is substantially greater than with other agents [39,40,41, 48, 76]. Although all insulin therapy is associated with weight gain, the extent of weight gain varies between the different insulins and regimens. In meta-analyses, weight gain with insulin analog therapy was found to positively correlate with insulin dosage [77] and to be greater with biphasic (premixed) insulin than with basal insulin alone [48, 76, 78]. However, weight gain is similar with premixed insulin and combination basal/prandial insulin [79].

In terms of different basal insulin formulations, insulin detemir (versus insulin glargine) has been associated with a lower increase in body weight when used in combination with oral antidiabetes drugs or with prandial insulin [79]. However, a pooled analysis found that, due to the lower A1C-lowering efficacy of insulin detemir, weight gain per mean A1C change was similar with both insulin analogs [80]. A recent meta-analysis including the latest generation of insulin analogs showed that treatment with insulin glargine 300 U/ml resulted in a comparable change in body weight to treatment with insulin detemir, NPH insulin, or insulin degludec, but significantly lower weight gain when compared with premixed insulin [81].

Guidelines recommend intensification to target postprandial glucose where A1C remains above target despite basal insulin being titrated to an acceptable fasting plasma glucose or if basal insulin dose exceeds 0.5 U/kg/day [8, 13]. Intensification can be achieved by adding either a rapid-acting insulin analog (basal plus or basal bolus), premixed insulin, or a GLP-1 RA [8, 13]. Alternatively, a once-daily, fixed-ratio combination of basal insulin in combination with a GLP-1 RA provides the advantage of drug delivery through a single daily injection with a lower risk of hypoglycemia. The weight-related advantages of GLP-1 RAs mentioned here should also be considered when intensifying therapy.

Conclusions

Current major guidelines recommend that when choosing antihyperglycemic treatments for patients who are overweight or have obesity, wherever possible, consideration should be given to medications that promote weight-loss or that are weight-neutral [8]. Given the benefits of weight-loss and the potential risks of weight gain in patients with T2D, the effect of antihyperglycemia agents on body weight is an important factor to take into account when individualizing patient therapy. Future developments should focus on increasing the number of agents for T2D that promote weight-loss, thus providing more options for patients.

References

Medical Research Council. Diabetes: facts and stats. https://www.mrc.ac.uk/documents/pdf/diabetes-uk-facts-and-stats-june-2015/. Accessed June 2018.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. Accessed June 2018.

Scheen AJ, Van Gaal LF. Combating the dual burden: therapeutic targeting of common pathways in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2:911–22.

Wing RR, Lang W, Wadden TA, et al. Benefits of modest weight loss in improving cardiovascular risk factors in overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1481–6.

Ross SA. Breaking down patient and physician barriers to optimize glycemic control in type 2 diabetes. Am J Med. 2013;126(9 Suppl 1):S38–48.

Peyrot M, Barnett AH, Meneghini LF, Schumm-Draeger PM. Insulin adherence behaviours and barriers in the multinational global attitudes of patients and physicians in insulin therapy study. Diabet Med. 2012;29:682–9.

Strain WD, Cos X, Hirst M, et al. Time to do more: addressing clinical inertia in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;105:302–12.

Davies MJ, D’Alessio DA, Fradkin J et al. Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes, 2018. A Consensus Report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2018. https://doi.org/10.2337/dci18-0033.

Eckel RH, Kahn SE, Ferrannini E, et al. Obesity and type 2 diabetes: what can be unified and what needs to be individualized? Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1424–30.

Sattar N, Gill JM. Type 2 diabetes as a disease of ectopic fat? BMC Med. 2014;12:123.

InterAct Consortium, Langenberg C, Sharp SJ, et al. Long-term risk of incident type 2 diabetes and measures of overall and regional obesity: the EPIC-InterAct case-cohort study. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001230.

Fang L, Guo F, Zhou L, Stahl R, Grams J. The cell size and distribution of adipocytes from subcutaneous and visceral fat is associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus in humans. Adipocyte. 2015;4:273–9.

Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI, et al. Consensus Statement by The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology on the Comprehensive Type 2 Diabetes Management Algorithm—2018 Executive Summary. Endocr Pract. 2018;24:91–120.

LaSalle JR, Berria R. Insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a practical approach for primary care physicians and other health care professionals. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2013;113:152–62.

US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health. Managing overweight and obesity in adults. Systematic evidence review from the obesity expert panel, 2013. Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/managing-overweight-obesity-in-adults. Accessed June 2018.

Khavandi K, Amer H, Ibrahim B, Brownrigg J. Strategies for preventing type 2 diabetes: an update for clinicians. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2013;4:242–6.

American Diabetes Association. Third-party reimbursement for diabetes care, self-management education, and supplies. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(Suppl 1):S87–8.

Medicare.gov. Nutrition therapy services. https://www.medicare.gov/coverage/nutrition-therapy-services.html. Accessed June 2018.

Medicare.gov. Diabetes self-management training. https://www.medicare.gov/coverage/diabetes-self-mgmt-training.html. Accessed June 2018.

Ali MK, Bullard KM, Saaddine JB, Cowie CC, Imperatore G, Gregg EW. Achievement of goals in US diabetes care, 1999–2010. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1613–24.

Robbins JM, Thatcher GE, Webb DA, Valdmanis VG. Nutritionist visits, diabetes classes, and hospitalization rates and charges: the Urban Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:655–60.

Look AHEAD Research Group. Eight-year weight losses with an intensive lifestyle intervention: the look AHEAD study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014;22:5–13.

Look AHEAD Research Group, Wing RR, Bolin P, et al. Cardiovascular effects of intensive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:145–54.

Dutton GR, Lewis CE. The Look AHEAD trial: implications for lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;58:69–75.

US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults—the evidence report. National Institutes of Health. Obes Res. 1998;6(Suppl 2):51S–209S.

Davies MJ, Bergenstal R, Bode B, et al. Efficacy of liraglutide for weight loss among patients with type 2 diabetes: the SCALE Diabetes Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2015;31:687–99.

Gadde KM, Allison DB, Ryan DH, et al. Effects of low-dose, controlled-release, phentermine plus topiramate combination on weight and associated comorbidities in overweight and obese adults (CONQUER): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2011;377:1341–52.

Greenway FL, Fujioka K, Plodkowski RA, et al. Effect of naltrexone plus bupropion on weight loss in overweight and obese adults (COR-I): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2010;376:595–605.

Hollander PA, Elbein SC, Hirsch IB, et al. Role of orlistat in the treatment of obese patients with type 2 diabetes. A 1-year randomized double-blind study. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1288–94.

Hollander P, Gupta AK, Plodkowski R, et al. Effects of naltrexone sustained-release/bupropion sustained-release combination therapy on body weight and glycemic parameters in overweight and obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:4022–9.

O’Neil PM, Smith SR, Weissman NJ, et al. Randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial of lorcaserin for weight loss in type 2 diabetes mellitus: the BLOOM-DM study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012;20:1426–36.

Pi-Sunyer X, Astrup A, Fujioka K, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of 3.0 mg of liraglutide in weight management. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:11–22.

Buchwald H, Estok R, Fahrbach K, et al. Weight and type 2 diabetes after bariatric surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2009;122:248–56.

Scarpello JH, Howlett HC. Metformin therapy and clinical uses. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2008;5:157–67.

Sherifali D, Nerenberg K, Pullenayegum E, Cheng JE, Gerstein HC. The effect of oral antidiabetic agents on A1C levels: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1859–64.

Golay A. Metformin and body weight. Int J Obes (Lond). 2008;32:61–72.

Malin SK, Kashyap SR. Effects of metformin on weight loss: potential mechanisms. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2014;21:323–9.

Phung OJ, Scholle JM, Talwar M, Coleman CI. Effect of noninsulin antidiabetic drugs added to metformin therapy on glycemic control, weight gain, and hypoglycemia in type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2010;303:1410–8.

Gross JL, Kramer CK, Leitão CB, et al. Effect of antihyperglycemic agents added to metformin and a sulfonylurea on glycemic control and weight gain in type 2 diabetes: a network meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:672–9.

McIntosh B, Cameron C, Singh SR, et al. Second-line therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with metformin monotherapy: a systematic review and mixed-treatment comparison meta-analysis. Open Med. 2011;5:e35–48.

McIntosh B, Cameron C, Singh SR, Yu C, Dolovich L, Houlden R. Choice of therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with metformin and a sulphonylurea: a systematic review and mixed-treatment comparison meta-analysis. Open Med. 2012;6:e62–74.

Derosa G, Maffioli P. α-Glucosidase inhibitors and their use in clinical practice. Arch Med Sci. 2012;8:899–906.

Kalra S, Baruah MP, Sahay RK, Unnikrishnan AG, Uppal S, Adetunji O. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: past, present, and future. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2016;20:254–67.

Meier JJ. GLP-1 receptor agonists for individualized treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012;8(12):728–42.

Trujillo JM, Nuffer W, Ellis SL. GLP-1 receptor agonists: a review of head-to-head clinical studies. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2015;6:19–28.

Valentine V, Goldman J, Shubrook JH. Rationale for, initiation and titration of the basal insulin/GLP-1RA fixed-ratio combination products, IDegLira and IGlarLixi, for the management of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2017;8:739–52.

Shyangdan DS, Royle P, Clar C, Sharma P, Waugh N, Snaith A. Glucagon-like peptide analogues for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;10:CD006423.

Lozano-Ortega G, Goring S, Bennett HA, Bergenheim K, Sternhufvud C, Mukherjee J. Network meta-analysis of treatments for type 2 diabetes mellitus following failure with metformin plus sulfonylurea. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32:807–16.

Davies M, Pieber TR, Hartoft-Nielsen ML, Hansen OKH, Jabbour S, Rosenstock J. Effect of oral semaglutide compared with placebo and subcutaneous semaglutide on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318:1460–70.

AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals. Symlin® (pramlintide acetate) Full Prescribing Information. 2014.

Singh-Franco D, Perez A, Harrington C. The effect of pramlintide acetate on glycemic control and weight in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and in obese patients without diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13:169–80.

Lee NJ, Norris SL, Thakurta S. Efficacy and harms of the hypoglycemic agent pramlintide in diabetes mellitus. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8:542–9.

Smith SR, Aronne LJ, Burns CM, Kesty NC, Halseth AE, Weyer C. Sustained weight loss following 12-month pramlintide treatment as an adjunct to lifestyle intervention in obesity. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1816–23.

Storgaard H, Gluud LL, Bennett C, et al. Benefits and harms of sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0166125.

Johnston R, Uthman O, Cummins E, et al. Canagliflozin, dapagliflozin and empagliflozin monotherapy for treating type 2 diabetes: systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2017;21:1–218.

Shyangdan DS, Uthman OA, Waugh N. SGLT-2 receptor inhibitors for treating patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e009417.

Li J, Gong Y, Li C, Lu Y, Liu Y, Shao Y. Long-term efficacy and safety of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors as add-on to metformin treatment in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e7201.

Kohler S, Salsali A, Hantel S, et al. Safety and tolerability of empagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes. Clin Ther. 2016;38:1299–313.

Xiong W, Xiao MY, Zhang M, Chang F. Efficacy and safety of canagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e5473.

Mearns ES, Sobieraj DM, White CM, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of antidiabetic drug regimens added to metformin monotherapy in patients with type 2 diabetes: a network meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0125879.

Neeland IJ, McGuire DK, Chilton R, et al. Empagliflozin reduces body weight and indices of adipose distribution in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2016;13:119–26.

Peene B, Benhalima K. Sodium glucose transporter protein 2 inhibitors: focusing on the kidney to treat type 2 diabetes. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2014;5:124–36.

Karagiannis T, Boura P, Tsapas A. Safety of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors: a perspective review. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2014;5:138–46.

Karagiannis T, Paschos P, Paletas K, Matthews DR, Tsapas A. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors for treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the clinical setting: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;344:e1369.

Liakopoulou P, Liakos A, Vasilakou D, et al. Fixed ratio combinations of glucagon like peptide 1 receptor agonists with basal insulin: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endocrine. 2017;56:485–94.

Wysham C, Bonadonna RC, Aroda VR, et al. Consistent findings in glycaemic control, body weight and hypoglycaemia with iGlarLixi (insulin glargine/lixisenatide titratable fixed-ratio combination) vs insulin glargine across baseline HbA1c, BMI and diabetes duration categories in the LixiLan-L trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19:1408–15.

Gough SC, Bode B, Woo V, et al. Efficacy and safety of a fixed-ratio combination of insulin degludec and liraglutide (IDegLira) compared with its components given alone: results of a phase 3, open-label, randomised, 26-week, treat-to-target trial in insulin-naive patients with type 2 diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2:885–93.

Rodbard H, Bode B, Harris S, et al. Safety and efficacy of insulin degludec/liraglutide (IDegLira) added to sulphonylurea alone or to sulphonylurea and metformin in insulin-naïve people with type 2 diabetes: the DUAL IV trial. Diabet Med. 2017;34:189–96.

Linjawi S, Bode B, Chaykin L, et al. The efficacy of IDegLira (insulin degludec/liraglutide combination) in adults with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with a GLP-1 receptor agonist and oral therapy: DUAL III randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Ther. 2017;8:101–14.

Lingvay I, Pérex Manghi F, García-Hernández P, et al. Effect of insulin glargine up-titration vs insulin degludec/liraglutide on glycated hemoglobin levels in patients with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes: the DUAL V randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315:898–907.

Buse JB, Vilsbøll T, Thurman J, et al. Contribution of liraglutide in the fixed-ratio combination of insulin degludec and liraglutide (IDegLira). Diabetes Care. 2014;37:2926–33.

Rosenstock J, Aronson R, Grunberger G, et al. Benefits of Lixilan, a titratable fixed-ratio combination of insulin glargine plus lixisenatide, versus insulin glargine and lixisenatide monocomponents in type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on oral agents: the LixiLan-O randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:2026–35.

Hirst JA, Farmer AJ, Dyar A, Lung TW, Stevens RJ. Estimating the effect of sulfonylurea on HbA1c in diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2013;56:973–84.

Schwartz S, Herman M. Revisiting weight reduction and management in the diabetic patient: novel therapies provide new strategies. Postgrad Med. 2015;127:480–93.

Fonseca V. Effect of thiazolidinediones on body weight in patients with diabetes mellitus. Am J Med. 2003;115(Suppl 8A):42S–8S.

Giugliano D, Maiorino MI, Bellastella G, Chiodini P, Ceriello A, Esposito K. Efficacy of insulin analogs in achieving the hemoglobin A1c target of < 7% in type 2 diabetes: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:510–7.

Pontiroli AE, Morabito A. Long-term prevention of mortality in morbid obesity through bariatric surgery. A systematic review and meta-analysis of trials performed with gastric banding and gastric bypass. Ann Surg. 2011;253:484–7.

Lasserson DS, Glasziou P, Perera R, Holman RR, Farmer AJ. Optimal insulin regimens in type 2 diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analyses. Diabetologia. 2009;52:1990–2000.

Rys P, Wojciechowski P, Rogoz-Sitek A, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials comparing efficacy and safety outcomes of insulin glargine with NPH insulin, premixed insulin preparations or with insulin detemir in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Acta Diabetol. 2015;52:649–62.

Dailey G, Admane K, Mercier F, Owens D. Relationship of insulin dose, A1c lowering, and weight in type 2 diabetes: comparing insulin glargine and insulin detemir. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2010;12:1019–27.

Freemantle N, Chou E, Frois C, et al. Safety and efficacy of insulin glargine 300 u/mL compared with other basal insulin therapies in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a network meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e009421.

Acknowledgements

Funding

Development of the manuscript and article processing charges and Open Access fee were funded by Sanofi US, Inc. All authors had full access to all data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Editorial Assistance

Editorial and writing support in the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Yasmin Issop, PhD, and Luke Shelton, PhD, of Excerpta Medica, funded by Sanofi US, Inc.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Disclosures

Caroline M. Apovian has received research funding from Aspire Bariatrics, GI Dynamics, Orexigen, Takeda, the Vela Foundation, Gelesis, Energesis, and Coherence Lab; has participated on the Advisory Boards for Nutrisystem, Zafgen, Sanofi, Orexigen, EnteroMedics, GI Dynamics, Scientific Intake, Gelesis, Novo Nordisk, SetPoint Health, Xeno Biosciences, Rhythm Pharmaceuticals, Eisai, and Takeda. Takeda Speakers Bureau for the medication Contrave. Ownership interest in Science Smart LLC. Jennifer Okemah has served on Sanofi Advisory Board, Sanofi Speakers Bureau, Dexcom Advisory Board, Dexcom/Sigma Speakers Bureau, Medtronic CPT, and Insulet CPT. Patrick M. O’Neil has received research grant support and honoraria from Novo Nordisk and has received honoraria from Robard Corp., Janssen, Vindico CME, and WebMD.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The information in this article is based on previously conducted studies and does not include any new report of findings not previously published by any of the authors.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7229018.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Apovian, C.M., Okemah, J. & O’Neil, P.M. Body Weight Considerations in the Management of Type 2 Diabetes. Adv Ther 36, 44–58 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-018-0824-8

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-018-0824-8