Abstract

Introduction

Continuous delivery of levodopa–carbidopa intestinal gel (LCIG) by percutaneous endoscopic gastrojejunostomy (PEG-J) in advanced Parkinson’s disease (PD) patients reduces variability in plasma levels, providing better control of motor fluctuations (“on” and “off” states). The MONOTREAT study assessed the effect of LCIG on activities of daily living, motor and non-motor symptoms, and quality of life in advanced PD patients.

Methods

This prospective, observational study included patients with advanced, levodopa-responsive PD with either 2–4 h of “off” time or 2 h of dyskinesia daily. Patients received LCIG via PEG-J for 16 h continuously. Effectiveness was assessed using Unified PD Rating Scale parts II and III, the Non-Motor Symptom Scale, and the PD Questionnaire-8.

Results

The mean (SD) treatment duration was 275 (157) days. Patients experienced significant improvement from baseline in activities of daily living at final visit (p < 0.05) as well as at months 3 and 6 (p < 0.0001). Patients also experienced significant improvements from baseline in quality of life and non-motor symptoms at all time points (p < 0.001 for all). Specifically, patients manifested significant improvements in mean change from baseline at every study visit in five of nine non-motor symptom score domains: sleep/fatigue, mood/cognition, gastrointestinal tract, urinary, and miscellaneous. One-third of patients (32.8%) experienced an adverse event; 21.9% experienced a serious adverse event; 11.1% discontinued because of an adverse event.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated significant and clinically relevant improvements in measures of activities of daily living, quality of life, and a specific subset of non-motor symptoms after treatment with LCIG.

Funding

AbbVie Inc.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Levodopa-related motor complications occur in the majority of patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) after 5–10 years of treatment [1]. The motor complications are attributed to progressive loss of striatal dopamine nerve terminals, the short half-life of levodopa, as well as variable gastric emptying and intestinal absorption leading to irregular plasma levodopa levels [2, 3].

In addition, patients manifest non-motor symptoms (e.g., cognitive deficits, sleep abnormalities, autonomic dysfunction), which can greatly impair a patient’s autonomy, resulting in increasing caregiver support and reduced quality of life. The prevalence of non-motor symptoms increases with disease severity but varies among the different domains and is patient specific [4, 5]. Several studies reported a strong contribution of non-motor symptoms on quality of life, confirming their relevance as therapeutic targets [4, 6,7,8].

Levodopa–carbidopa intestinal gel [LCIG, Duodopa®, carbidopa levodopa enteral suspension in the USA (CLES, Duopa®), AbbVie Inc, North Chicago, IL, USA] is continuously delivered via percutaneous endoscopic gastrojejunostomy (PEG-J) in patients with advanced PD who have motor fluctuations and dyskinesia not adequately managed by available orally administered anti-Parkinsonian medications. Continuous delivery by PEG-J reduces variability in plasma levels by avoiding the effects of erratic gastric emptying [9]. This strategy reduces “off” time and improves quality of life in patients with advanced PD in a controlled setting [6, 10,11,12,13,14]. Previous studies have reported extensively on the safety and efficacy of LCIG in controlled settings; however, there is a dearth of “real-life” data available on the use of LCIG in clinical practice. Further, these studies have typically included patients with advanced PD as well as long disease duration. The objective of this study was to assess the effect of LCIG treatment on activities of daily living, motor and non-motor symptoms, and quality of life in patients as they start presenting with motor complications.

Methods

Patients

Patients were eligible to participate in the study if they fulfilled the following criteria at baseline: patients were diagnosed with advanced, levodopa-responsive PD; patients’ physicians chose to use LCIG to treat patients’ PD in accordance with the local approved use before any decision was made to solicit a patient’s participation in this study; patients had unchanged PD treatment for at least 4 weeks before the baseline visit; patients received four or more daily oral doses of PD medication; and patients had 2–4 h of “off” time or 2 h of non-troublesome or troublesome dyskinesia daily supported by a Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) total score in the best “on” state of at least 40 points at baseline [15, 16]. Patients were excluded if they had been treated with deep brain stimulation (DBS), used apomorphine pump, received LCIG treatment before the baseline visit, or had evidence for clinically relevant cognitive deficits, as defined by a score less than 24 on the mini-mental state examination.

Study Design and Treatment

This prospective, post-marketing observational study was performed in an international, multicenter setting at 30 sites. There were five target visits: baseline; hospital discharge; and months 3, 6, and 12 after hospital discharge. A temporary naso-jejunal tube was used for LCIG administration to determine if the patient responded favorably to LCIG and to optimize the dose before treatment was initiated via PEG-J tube. LCIG was administered directly into the proximal small intestine through a jejunal extension tube using a portable infusion pump. Patients who chose not to continue LCIG treatment after the temporary naso-jejunal test phase as well as patients who discontinued LCIG treatment during the study had the option to continue the study in the standard-of-care group (orally and/or transdermally administered anti-Parkinson’s disease medications that patients were taking prior to consideration for LCIG treatment). If, during the study, a patient chose to be treated with apomorphine pump or DBS, the patient was no longer eligible to continue in the study. This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964, as revised in 2013, good clinical practice, and applicable local legal and regulatory requirements. All patients provided written informed consent.

Assessments

Effectiveness

The primary endpoint was the change from baseline to final visit in a patient’s impairment in activities of daily living as measured by UPDRS Part II (score range 0–52; a higher score indicates a greater impairment; measured during the best “on” time). Secondary endpoints included the change from baseline in activities of daily living at other time points; UPDRS Part III and IV scores (measured during the best “on” time), scores on the Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire-8 (PDQ-8) summary index (assessing quality of life; score normalized to a scale of 0–100, with a higher summary index indicating a greater impairment); and scores on the Non-Motor Symptoms Scale (NMSS) and subdomains, which assessed non-motor symptoms over the previous month (total NMSS score range 0–360, with a higher score indicating more severe symptoms).

Safety

Safety was assessed by adverse events (AEs) and product complaints. Investigators identified the severity and seriousness of AEs, and indicated their opinion of the relationship of the AE to LCIG (reasonable possibility or not).

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS® version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Significant changes from baseline in the LCIG group were assessed using two-sided t tests. “Final” endpoints included data from month 12 with the last observation carried forward for missing values. The standard-of-care treatment group was not powered for statistical analysis; as such, statistical comparisons were not made within the standard-of-care treatment group nor between the standard of care and LCIG treatment groups.

Results

Patients

Patient baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. The majority of patients in this study were male, and the average age was 70.4 (7.8) years. The average PD duration was 13.9 (5.4) years and the most common previous PD therapies were orally administered levodopa (100%) and dopamine agonists (94%).

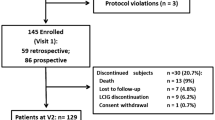

Overall, 65 patients were screened and 64 patients began treatment via naso-jejunal tube (Fig. 1). One patient was excluded because of a protocol violation. A total of 58 (89%) continued to LCIG treatment via PEG-J after the initial naso-jejunal test phase. Six (9%) patients returned to the standard-of-care group after starting LCIG therapy via a naso-jejunal tube and prior to PEG-J placement (please see Supplemental Table 1 for detailed patient disposition by visit).

The mean (SD) study duration was 308 (129) days (range 1–546 days); the mean (SD) LCIG treatment duration was 275 (157) days (range 2–545 days). Forty-one patients (63%) completed all 12 months of LCIG treatment. Over the course of the study, 16 patients (25%) switched to the standard-of-care group (orally and/or transdermally administered dopaminergic therapy), although only six remained in the standard-of-care group through month 12. Of patients who did not remain in the standard-of-care group, one patient opted for an excluded surgical treatment and nine patients discontinued participation in the study (or there was no treatment information).

A total of 23 patients (35.9%) discontinued LCIG treatment during the study, most commonly by patients’ decision (nine patients, 14.1%), or by the investigator as a result of a medical event (eight patients, 12.5%) (please see Supplemental Table 2 for reasons for discontinuation).

Effectiveness

LCIG Treatment Group

In patients receiving LCIG, there was a significant improvement from baseline in patients’ abilities to perform activities of daily living (UPDRS Part II) at the final visit [mean (SD) change from baseline of −2.1 (6.9); p < 0.05] (Fig. 2). Results were also significant at months 3 and 6 (p < 0.0001); an improvement of −1.8 (7.1) from baseline at month 12 was not significant.

Mean (SD) change from baseline in measures of activities of daily living in the LCIG treatment group. Activities of daily living were measured by UPDRS Part II total score during the best “on” time. Statistical significance compared with baseline is indicated at p ≤ 0.05 (single asterisk) and p ≤ 0.0001 (triple asterisk). “Final” is the last observation carried forward. LCIG levodopa–carbidopa intestinal gel, UPDRS Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale

Patients receiving LCIG experienced significant improvements from baseline in motor symptoms at all time points, as measured by UPDRS Part III total score (p < 0.0001 at all time points, Fig. 3a). The largest improvement from baseline was seen after 3 months of treatment [mean (SD) change from baseline of −12.9 (16.2)]; improvements from baseline were around −9 thereafter. Patients receiving LCIG had a significant mean decrease from baseline in the PDQ-8 summary index score at all time points (p < 0.0001 at month 3 and 6; p < 0.001 at month 12 and final; Fig. 3b). The mean change in the NMSS total score from baseline was significant at every time point in patients receiving LCIG (p < 0.0001), indicating that the significant improvement in non-motor symptoms was sustained over time (Fig. 3c). Patients manifested significant improvements in the mean change from baseline at every study visit in five of the nine NMSS domains: sleep/fatigue, mood/cognition, gastrointestinal tract, urinary, and miscellaneous (Table 2).

Mean (SD) change from baseline in measures of a motor symptoms, b quality of life, and c non-motor symptoms in the LCIG treatment group. Motor symptoms were measured by UPDRS Part III total score during the best “on” time; quality of life was measured by PDQ-8 summary index score; non-motor symptoms were measured using the NMSS total score. Statistical significance compared with baseline is indicated at p ≤ 0.01 (double asterisk) and p ≤ 0.0001 (triple asterisk). “Final” is the last observation carried forward. LCIG levodopa–carbidopa intestinal gel, NMSS Non-Motor Symptom Scale, PDQ-8 Parkinson’s disease questionnaire, UPDRS Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale

Standard-of-Care Treatment Group

Patients in the standard-of-care group demonstrated small improvements from baseline of −1.5 (2.3) in UPDRS Part II total score at month 6, although the mean change from baseline at month 12 of 0.5 (5.3) indicates that there was no improvement from baseline at month 12 in the standard-of-care group (Supplemental Fig. 1A). Patients in the standard-of-care group also experienced some improvement from baseline in UPDRS Part III total score at months 3, 6, and at the final measurement (Supplemental Fig. 1B). Patients in the standard-of-care group experienced reductions from baseline in PDQ-8 summary index scores and numerical/formal improvements from baseline in non-motor symptoms at all time points (Supplemental Fig. 1C, D). Patients experienced improvements at each visit in four of nine NMSS subdomains: cardiovascular, mood/cognition, gastrointestinal, and miscellaneous (Supplemental Table 3). The small number of patients in the standard-of-care group did not allow for any statistical analyses.

Safety

One-third of the patients (32.8%) experienced an AE. Eight patients (12.7%) experienced AEs that were considered to be possibly related to LCIG, as rated by the study investigator. Adverse events occurring in two or more patients included stoma site infection (4.7%), therapy cessation (4.7%), and psychotic disorder (3.1%). Of the 14 patients (21.9%) who experienced a serious AE, two patients (3.1%) experienced a psychotic disorder. Two patients (3.1%) experienced serious AEs reported by the study investigator to have a reasonable possibility of being related to the treatment: one patient had dopamine dysregulation syndrome, overdosed on orally administered levodopa/entacapone, suffered psychosis, and was hospitalized; the other patient had a mild lung infection and severe dystonia of both legs. Two patients (3.1%) died during the study (causes of death: cardiac failure and sudden death); both deaths were deemed by the investigator as having no reasonable possibility of being related to LCIG. Seven patients (11.1%) discontinued LCIG treatment because of AEs, including one of each of the following AEs: peristomal fasciitis, peritonitis, gastrostomy tube infection, dopaminergic dysregulation syndrome, severe dystonia, lack of clinical improvement, and a severed tube. Three AEs (stoma site infection, peristomal granuloma and gastric secretion, and peristomal fasciitis) were associated with three different product complaints and were reported in one patient each.

Discussion

Results from this prospective, multicenter, observational study showed significant improvements in activities of daily living, motor and non-motor symptoms, and quality-of-life scores, with safety results in accord with the known safety profile of LCIG [11, 12, 17]. These results extend current findings, which have focused primarily on the effect of LCIG on motor complications [10,11,12, 14]. As it has recently been suggested that there is a relationship between improvements in motor UPDRS and NMSS scores [18], assessing the effect of both motor and non-motor symptoms on quality of life will be a boon to patients with advanced PD.

General disease progression and gradual deterioration of activities of daily living have been reported to occur at an average yearly decline in UPDRS Part II scores of 0.56 (measured during “on” time) [19]. In the current study, LCIG treatment led to significant improvements in patients’ activities of daily living from baseline to the final visit (primary endpoint), and at 3 and 6 months after starting LCIG therapy. The minimal clinically important difference in UPDRS part II scores has been previously determined to be 1.8 [15]; results from the current study indicated improvements of 1.8 or more as observed at all time points. Patients treated with LCIG also experienced significant improvements from baseline in motor symptoms at each time point. The greatest improvement in UPDRS Part III scores was −12.9 at month 3; improvements in motor skills were sustained around −9 for the remainder of the study. The minimal clinically important difference in UPDRS part III scores has been previously reported to be 2.5 points, with moderate improvement classified as 5.2 points, and large improvement at 10.8 points [20]. On the basis of these criteria, patients in this study experienced moderate-to-large clinically important improvements in motor symptoms.

Non-motor symptoms have been shown to negatively impact quality of life in both patients and caregivers [4, 6,7,8, 21]. However, non-motor symptoms are frequently not well recognized and assessed in clinical practice [22]. In this study, patients treated with LCIG experienced significant improvements from baseline in non-motor symptoms, with corresponding improvements in quality of life (as measured by PDQ-8), at all time points. Overall improvements from baseline in quality of life and non-motor symptoms were similar to those reported in other observational, routine-care studies [23, 24]. Patients experienced significant improvements from baseline for sleep/fatigue, mood/cognition, gastrointestinal tract, urinary, and miscellaneous NMSS subscores. LCIG treatment has previously demonstrated a varied degree of significant improvement in these same subdomains in other studies [6, 23,24,25]. When compared with results in other studies assessing non-motor symptoms in patients receiving LCIG, patients in the current study exhibited greater improvements in mood/cognition, less improvement in sleep/fatigue, and improvements in gastrointestinal and urinary symptoms in between the improvements seen in other studies [6, 23]. Patients treated with DBS have demonstrated significant improvement in NMSS total score and six of nine subdomains, although improvements in these patients were generally of smaller magnitude than in the current study (except for sleep/fatigue) [26], which may account for the larger improvements in quality of life experienced by patients undergoing LCIG treatment. Treatment with apomorphine infusion has also demonstrated significant improvements in NMSS total score and in six of nine subdomains; improvements in urinary function were not to the same degree as noted in the current study [24]. Among the variety of non-motor symptoms observed in PD patients, it was recently shown that mood was consistently among the most important predictors for an impact on quality of life [21, 27, 28], which further underscores the relevance of the observed greater improvement in mood/cognition in the present study.

Individuals in the standard-of-care treatment group did show some numerical/formal and/or transient improvements from baseline in activities of daily living, quality of life, and non-motor symptoms. However, the size of the standard-of-care group was small, and the size fluctuated over the course of the study, as patients could switch to the standard-of-care group at any time during the study. Consequently, patients who may have initially been treated with LCIG before switching to the standard of care may have altered the outcomes in the standard-of-care group. Further, the variability and small size of the standard-of-care group precluded any statistical analyses and any comparisons between groups.

The safety results were consistent with the established safety profile of LCIG [11, 12, 17]; no new safety concerns were reported or detected. The most common AEs were related to maintenance of the stoma site. It has been reported that there is considerable potential for gastrointestinal serious adverse events with LCIG treatment [29]; however, in this study, there was only one incident of peritonitis, and all gastrointestinal serious adverse events were not considered to be related to the treatment. In addition, axonal neuropathy has been reported in patients treated with LCIG [30]; however, there were no reports of neuropathy in the current study. Although there was a relatively high (35.9%) overall rate of discontinuation from LCIG treatment, in only 11.1% of patients it was due to AEs.

Interestingly, patients in this study tended to be older (mean age of 70.4 vs. 64 years) and have a longer disease duration (mean duration of 14 vs. 12.5 years) than patients in a previous open-label study, despite similar inclusion criteria [11]. Moreover, the magnitude of improvement of activities of daily living (as assessed by UPDRS II) was smaller than previously reported (−2.1 vs. −4.4). The observed older age of patients included in the present study could have an impact on the treatment response and benefit, as it has been shown for other interventional therapies [31, 32].

A limitation of this study design is that the effectiveness measures were based on self-reported assessments and did not include a diary to assess motor benefit. Because this study was conducted as an observation of routine care with LCIG, these outcomes are considered to be close to what may be observed in real-world clinical practice. Nonetheless, this study was limited by the observational design and the lack of a true control group. Because patients in the standard-of-care group could have initiated LCIG before they decided to transition back to standard-of-care treatment (and also back to LCIG), no direct comparisons or statistical analyses can be made between the groups. Further prospective randomized controlled studies are needed to assess the differences between LCIG and standard of care in activities of daily living, non-motor symptoms, and quality of life.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated significant and clinically relevant improvements in measures of activities of daily living, motor and non-motor symptoms, and quality of life after treatment with LCIG. Despite a relatively high rate of discontinuation, these data indicate that in addition to the previously reported safety and efficacy, LCIG also provides significant benefits to activities of daily living, non-motor symptoms, and quality of life in patients with advanced PD.

References

Ahlskog JE, Muenter MD. Frequency of levodopa-related dyskinesias and motor fluctuations as estimated from the cumulative literature. Mov Disord. 2001;16(3):448–58.

Hardoff R, Sula M, Tamir A, et al. Gastric emptying time and gastric motility in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2001;16(6):1041–7.

Contin M, Martinelli P. Pharmacokinetics of levodopa. J Neurol. 2010;257(Suppl 2):S253–61.

Martinez-Martin P, Schapira AH, Stocchi F, et al. Prevalence of nonmotor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease in an international setting; study using nonmotor symptoms questionnaire in 545 patients. Mov Disord. 2007;22(11):1623–9.

Antonini A, Barone P, Marconi R, et al. The progression of non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease and their contribution to motor disability and quality of life. J Neurol. 2012;259(12):2621–31.

Honig H, Antonini A, Martinez-Martin P, et al. Intrajejunal levodopa infusion in Parkinson’s disease: a pilot multicenter study of effects on nonmotor symptoms and quality of life. Mov Disord. 2009;24(10):1468–74.

Estrada-Bellmann I, Camara-Lemarroy CR, Calderon-Hernandez HJ, Rocha-Anaya JJ, Villareal-Velazquez HJ. Non-motor symptoms and quality of life in patients with Parkinson’s disease in Northeastern Mexico. Acta Neurol Belg. 2016;116(2):157–61.

Santos-Garcia D, de la Fuente-Fernandez R. Impact of non-motor symptoms on health-related and perceived quality of life in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Sci. 2013;332(1–2):136–40.

Othman AA, Chatamra K, Mohamed ME, et al. Jejunal Infusion of levodopa–carbidopa intestinal gel versus oral administration of levodopa–carbidopa tablets in Japanese subjects with advanced Parkinson’s disease: pharmacokinetics and pilot efficacy and safety. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2015;54(9):975–84.

Olanow CW, Kieburtz K, Odin P, et al. Continuous intrajejunal infusion of levodopa–carbidopa intestinal gel for patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease: a randomised, controlled, double-blind, double-dummy study. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(2):141–9.

Fernandez HH, Standaert DG, Hauser RA, et al. Levodopa–carbidopa intestinal gel in advanced Parkinson’s disease: final 12-month, open-label results. Mov Disord. 2015;30(4):500–9.

Slevin JT, Fernandez HH, Zadikoff C, et al. Long-term safety and maintenance of efficacy of levodopa–carbidopa intestinal gel: an open-label extension of the double-blind pivotal study in advanced Parkinson’s disease patients. J Parkinsons Dis. 2015;5(1):165–74.

Puente V, De Fabregues O, Oliveras C, et al. Eighteen month study of continuous intraduodenal levodopa infusion in patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease: impact on control of fluctuations and quality of life. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2010;16(3):218–21.

Antonini A, Fung VS, Boyd JT, et al. Effect of levodopa–carbidopa intestinal gel on dyskinesia in advanced Parkinson’s disease patients. Mov Disord. 2016;31(4):530–7.

Hauser RA, Gordon MF, Mizuno Y, et al. Minimal clinically important difference in Parkinson’s disease as assessed in pivotal trials of pramipexole extended release. Parkinsons Dis. 2014;2014:467131.

Hauser RA, Auinger P, Parkinson Study Group. Determination of minimal clinically important change in early and advanced Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2011;26(5):813–8.

Lang AE, Rodriguez RL, Boyd JT, et al. Integrated safety of levodopa–carbidopa intestinal gel from prospective clinical trials. Mov Disord. 2016;31(4):538–46.

Muller T, Ohm G, Eilert K, et al. Benefit on motor and non-motor behavior in a specialized unit for Parkinson’s disease. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2017;124(6):715–20.

Jankovic J, Kapadia AS. Functional decline in Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 2001;58(10):1611–5.

Shulman LM, Gruber-Baldini AL, Anderson KE, Fishman PS, Reich SG, Weiner WJ. The clinically important difference on the unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale. Arch Neurol. 2010;67(1):64–70.

Martinez-Martin P, Rodriguez-Blazquez C, Kurtis MM, Chaudhuri KR, NMSS Validation Group. The impact of non-motor symptoms on health-related quality of life of patients with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2011;26(3):399–406.

Chaudhuri KR, Prieto-Jurcynska C, Naidu Y, et al. The nondeclaration of nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease to health care professionals: an international study using the nonmotor symptoms questionnaire. Mov Disord. 2010;25(6):704–9.

Antonini A, Yegin A, Preda C, et al. Global long-term study on motor and non-motor symptoms and safety of levodopa–carbidopa intestinal gel in routine care of advanced Parkinson’s disease patients; 12-month interim outcomes. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2015;21(3):231–5.

Martinez-Martin P, Reddy P, Katzenschlager R, et al. EuroInf: a multicenter comparative observational study of apomorphine and levodopa infusion in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2015;30(4):510–6.

Reddy P, Martinez-Martin P, Rizos A, et al. Intrajejunal levodopa versus conventional therapy in Parkinson disease: motor and nonmotor effects. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2012;35(5):205–7.

Dafsari HS, Reddy P, Herchenbach C, et al. Beneficial effects of bilateral subthalamic stimulation on non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Stimul. 2016;9(1):78–85.

Prakash KM, Nadkarni NV, Lye WK, Yong MH, Tan EK. The impact of non-motor symptoms on the quality of life of Parkinson’s disease patients: a longitudinal study. Eur J Neurol. 2016;23(5):854–60.

Liu WM, Lin RJ, Yu RL, Tai CH, Lin CH, Wu RM. The impact of nonmotor symptoms on quality of life in patients with Parkinson’s disease in Taiwan. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:2865–73.

Klostermann F, Jugel C, Bomelburg M, Marzinzik F, Ebersbach G, Muller T. Severe gastrointestinal complications in patients with levodopa/carbidopa intestinal gel infusion. Mov Disord. 2012;27(13):1704–5.

Jugel C, Ehlen F, Taskin B, Marzinzik F, Muller T, Klostermann F. Neuropathy in Parkinson’s disease patients with intestinal levodopa infusion versus oral drugs. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e66639.

Bouwyn JP, Derrey S, Lefaucheur R, et al. Age limits for deep brain stimulation of subthalamic nuclei in Parkinson’s disease. J Parkinsons Dis. 2016;6(2):393–400.

Derost PP, Ouchchane L, Morand D, et al. Is DBS-STN appropriate to treat severe Parkinson disease in an elderly population? Neurology. 2007;68(17):1345–55.

Acknowledgements

Financial support for this study, as well as funding for the article processing charges and open access fee associated with this manuscript, was provided by AbbVie Inc., North Chicago, IL, USA. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published. Rejko Krüger, Paul Lingor, Triantafyllos Doskas, Johanna Henselmans, Erik H. Danielsen, Oriol de Fabregues, Alessandro Stefani, Koray Onuk, and Angelo Antonini acquired and interpreted the data and reviewed and critiqued the manuscript throughout the editorial process. Sven-Christian Sensken, Juan Carlos Parra, and Ashley Yegin were responsible for original research project conception and design, and reviewed and critiqued the manuscript throughout the editorial process. Juan Carlos Parra also performed statistical analysis. Data included in this manuscript were previously presented at the 20th International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders, June 19–21, 2016, in Berlin, Germany, at the 11th International Congress on Non-Motor Dysfunctions in Parkinson’s Disease and Related Disorders, October 6–8, 2016, in Ljubljana, Slovenia, as well as at the Austrian Parkinson Society (ÖPG) Annual Meeting, October 20–22, 2016, in Graz, Austria.

Medical writing assistance was provided by Kelly M. Cameron, PhD, of JB Ashtin, who, on behalf of AbbVie Inc., helped prepare the first draft and implemented author revisions throughout the editorial process. Support for this assistance was funded by AbbVie Inc.

Disclosures

Rejko Krüger was a study investigator. He has received research grants from the German Research Council (DFG: KR2119/8-1), the Michael J Fox Foundation, the Fritz Thyssen Foundation (10.11.2.153), the Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF, NGFNplus; 01GS08134), the Fonds National de Recherche Luxembourg (FNR; PEARL and NCER-PD), and from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement No. 692320 (TWINNING; Centre-PD). He has received speakers’ honoraria and/or travel grants from UCB Pharma, AbbVie, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, St Jude, and Medtronic. Paul Lingor was a study investigator and received speaker honoraria and/or travel grants from AbbVie, Licher MT, Medtronic, BayerVital, and Zambon. His research has been supported by the German Research Council (DFG), the Michael J Fox Foundation, and the Else Kröner-Fresenius Stiftung. Triantafyllos Doskas was a study investigator, and has received speaker/consulting honoraria from Merck, Novartis, Teva, Actellion, and Genesis. Erik H Danielsen was a study investigator and has no other conflicts of interest to disclose. Alessandro Stefani was a study investigator and has no other conflicts of interest to disclose. Johanna Henselmans was a study investigator and did not receive any personal funding from AbbVie over the past year. Oriol de Fabregues was a study investigator and has received speaker honoraria from AbbVie and Zambon; he reports no other financial conflicts of interest. Sven-Christian Sensken is an employee of AbbVie Deutschland GmbH & Co KG. Juan Carlos Parra is an employee of AbbVie Inc, and holds AbbVie stock and/or stock options. Koray Onuk is an employee of AbbVie Inc, and holds AbbVie stock and/or stock options. Ashley Yegin is an employee of AbbVie Inc, and holds AbbVie stock and/or stock options. Angelo Antonini has received honoraria for consulting services and symposia from AbbVie. This study was funded by AbbVie Inc. AbbVie participated in the study design, research, data collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, writing, reviewing, and approving the manuscript for publication.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, as revised in 2013. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Data Availability

The clinical study report synopsis is available on AbbVie.com. Requests for additional trial data can be made at http://abbvie.com.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/4998F0605DE851C0.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Krüger, R., Lingor, P., Doskas, T. et al. An Observational Study of the Effect of Levodopa–Carbidopa Intestinal Gel on Activities of Daily Living and Quality of Life in Advanced Parkinson’s Disease Patients. Adv Ther 34, 1741–1752 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-017-0571-2

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-017-0571-2