Abstract

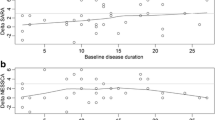

Spinocerebellar ataxia type 31 (SCA31) is known as a late-onset, relatively pure cerebellar form of ataxia, but a longitudinal prospective study on the natural history of SCA31 has not been done yet. In this prospective cohort study, we enrolled 44 patients (mean ± standard deviation 73.6 ± 8.5 years) with genetically confirmed SCA31 from 10 ataxia referral centers in the Nagano area, Japan. Patients were evaluated every year for 4 years using the Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (SARA) and the Barthel Index (BI). Of the 176 follow-up visits (91.5%), 161 were completed in this study. Five patients (11.4%) died during the follow-up period, and two patients (4.5%) were lost to follow-up. The annual progression of the SARA score was 0.8 ± 0.1 points/year and that of the BI was −2.3 ± 0.4 points/year (mean ± standard error). Shorter disease duration at baseline was associated with faster progression of the SARA score. Our study indicated the averaged clinical course of SCA31 as follows: the patients develop ataxic symptoms at 58.5 ± 10.3 years, become wheelchair bound at 79.4 ± 1.7 years, and died at 88.5 ± 0.7 years. Our prospective dataset provides important information for clinical trials of forthcoming disease-modifying therapies for cerebellar ataxia. It also represents a useful resource for SCA31 patients and their family members in genetic counseling sessions.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ouyang Y, Sakoe K, Shimazaki H, Namekawa M, Ogawa T, Ando Y, et al. 16q-linked autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia: a clinical and genetic study. J Neurol Sci. 2006;247:180–6.

Onodera Y, Aoki M, Mizuno H, Warita H, Shiga Y, Itoyama Y. Clinical features of chromosome 16q22.1 linked autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia in Japanese. Neurology. 2006;67:1300–2.

Nozaki H, Ikeuchi T, Kawakami A, Kimura A, Koide R, Tsuchiya M, et al. Clinical and genetic characterizations of 16q-linked autosomal dominant spinocerebellar ataxia (AD-SCA) and frequency analysis of AD-SCA in the Japanese population. Mov Disord. 2007;22:857–62.

Basri R, Yabe I, Soma H, Sasaki H. Spectrum and prevalence of autosomal dominant spinocerebellar ataxia in Hokkaido, the northern island of Japan: a study of 113 Japanese families. J Hum Genet. 2007;52:848–55.

Hayashi M, Adachi Y, Mori M, Nakano T, Nakashima K. Clinical and genetic epidemiological study of 16q22.1-linked autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia in western Japan. Acta Neurol Scand. 2007;116:123–7.

Yoshida K, Shimizu Y, Morita H, Okano T, Sakai H, Ohata T, et al. Severity and progression rate of cerebellar ataxia in 16q-linked autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia (16q-ADCA) in the endemic Nagano area of Japan. Cerebellum. 2009;8:46–51.

Sakai H, Yoshida K, Shimizu Y, Morita H, Ikeda S, Matsumoto N. Analysis of an insertion mutation in a cohort of 94 patients with spinocerebellar ataxia type 31 from Nagano, Japan. Neurogenetics. 2010;11:409–15.

Sato N, Amino T, Kobayashi K, Asakawa S, Ishiguro T, Tsunemi T, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 31 is associated with “inserted” penta-nucleotide repeats containing (TGGAA)n. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85:544–57.

Niimi Y, Takahashi M, Sugawara E, Umeda S, Obayashi M, Sato N, et al. Abnormal RNA structures (RNA foci) containing a penta-nucleotide repeat (UGGAA)n in the Purkinje cell nucleus is associated with spinocerebellar ataxia type 31 pathogenesis. Neuropathology. 2013;33:600–11.

Jacobi H, du Montcel ST, Bauer P, Giunti P, Cook A, Labrum R, et al. Long-term disease progression in spinocerebellar ataxia types 1, 2, 3, and 6: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:1101–8.

Ashizawa T, Figueroa KP, Perlman SL, Gomez CM, Wilmot GR, Schmahmann JD, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with spinocerebellar ataxias 1, 2, 3 and 6 in the US; a prospective observational study. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:177.

Velázquez-Pérez L, Rodríguez-Labrada R, Canales-Ochoa N, Montero JM, Sánchez-Cruz G, Aguilera-Rodríguez R, et al. Progression of early features of spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 in individuals at risk: a longitudinal study. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:482–9.

Tezenas du Montcel S, Charles P, Goizet C, Marelli C, Ribai P, Vincitorio C, et al. Factors influencing disease progression in autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia and spastic paraplegia. Arch Neurol. 2012;69:500–8.

Lee YC, Liao YC, Wang PS, Lee IH, Lin KP, Soong BW. Comparison of cerebellar ataxias: a three-year prospective longitudinal assessment. Mov Disord. 2011;26:2081–7.

Yasui K, Yabe I, Yoshida K, Kanai K, Arai K, Ito M, et al. A 3-year cohort study of the natural history of spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 in Japan. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:118.

Shintaku M, Kaneda D. Chromosome 16q-22.1-linked autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia: an autopsy case report with some new observations on cerebellar pathology. Neuropathology. 2009;29:285–92.

Ishikawa K, Mizusawa H. The chromosome 16q-linked autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia (16q-ADCA*): a newly identified degenerative ataxia in Japan showing peculiar morphological changes of the Purkinje cell. Neuropathology. 2010;30:490–4.

Yoshida K, Asakawa M, Suzuki-Kouyama E, Tabata K, Shintaku M, Ikeda S, Oyanagi K. Distinctive features of degenerating Purkinje cells in spinocerebellar ataxia type 31. Neuropathology. 2014;34:261–7.

Tada M, Nishizawa M, Onodera O. Redefining cerebellar ataxia in degenerative ataxias: lessons from recent research on cerebellar systems. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015;86:922–8.

Ishikawa K, Dürr A, Klopstock T, Müller S, De Toffol B, Vidailhet M, et al. Pentanucleotide repeats at the spinocerebellar ataxia type 31 (SCA31) locus in Caucasians. Neurology. 2011;77:1853–5.

Lee YC, Liu CS, Lee TY, Lo YC, Lu YC, Soong BW. SCA31 is rare in the Chinese population on Taiwan. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:426. e423–4.

Pedroso JL, Abrahao A, Ishikawa K, Raskin S, de Souza PV, de Rezende Pinto WB, et al. When should we test patients with familial ataxias for SCA31? A misdiagnosed condition outside Japan? J Neurol Sci. 2015;355:206–8.

Schmitz-Hübsch T, du Montcel ST, Baliko L, Berciano J, Boesch S, Depondt C, et al. Scale for the assessment and rating of ataxia—development of a new clinical scale. Neurology. 2006;66:1717–20.

Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61–5.

Jacobi H, Rakowicz M, Rola R, Fancellu R, Mariotti C, Charles P, et al. Inventory of non-ataxia signs (INAS): validation of a new clinical assessment instrument. Cerebellum. 2013;12:418–28.

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Japan demographics profile. 2014. (online) Available at: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/life/life14/. Accessed 22 Feb 2016.

Koob MD, Moseley ML, Schut LJ, Benzow KA, Bird TD, Day JW, et al. An untranslated CTG expansion causes a novel form of spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA8). Nat Genet. 1999;21:379–84.

Harley HG, Brook JD, Rundle SA, Crow S, Reardon W, Buckler AJ, et al. Expansion of an unstable DNA region and phenotypic variation in myotonic dystrophy. Nature. 1992;355:545–6.

Liquori CL, Ricker K, Moseley ML, Jacobsen JF, Kress W, Naylor SL, et al. Myotonic dystrophy type 2 caused by a CCTG expansion in intron 1 of ZNF9. Science. 2001;293:864–7.

Bernat V, Disney MD. RNA structures as mediators of neurological diseases and as drug targets. Neuron. 2015;87:28–46.

Matsushima A, Yoshida K, Genno H, Murata A, Matsuzawa S, Nakamura K, et al. Clinical assessment of standing and gait in ataxic patients using a triaxial accelerometer. Cerebellum Ataxias. 2015;2:9.

Shirai S, Yabe I, Matsushima M, Ito YM, Yoneyama M, Sasaki H, et al. Quantitative evaluation of gait ataxia by accelerometers. J Neurol Sci. 2015;358:253–8.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Drs. Jun Miki, Kazuma Kaneko, Akiyo Hineno, Daigo Miyazaki, Chinatsu Kobayashi, Ken Takasone, Kazuki Ozawa, Michiaki Kinoshita, and Ryuta Abe for their contribution to the inclusion of the patients in this study. The authors thank Ms. Emi Nomura and Ms. Sonomi Nagasaki for their technical support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Source of Funding

This study was supported in part by a grant from the Research Committee for Ataxic Diseases, the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, Japan (K. Yoshida).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Figure e-1

Flowchart for the annual follow-up of patients with SCA31. (JPEG 47 kb)

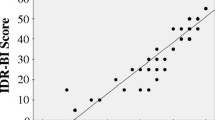

Figure e-2

Correlation between the total SARA score and BI in patients with SCA31 (n = 205 follow-ups). (JPEG 35 kb)

Figure e-3

Required sample size per group in two-group interventional trials of 1-year duration in SCA31 for various effect sizes. (JPEG 36 kb)

Table e-1

Change in the SARA subscores from baseline to Visit 5. (DOCX 16 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nakamura, K., Yoshida, K., Matsushima, A. et al. Natural History of Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 31: a 4-Year Prospective Study. Cerebellum 16, 518–524 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-016-0833-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-016-0833-6