Abstract

A role for the cerebellum in causing ataxia, a disorder characterized by uncoordinated movement, is widely accepted. Recent work has suggested that alterations in activity, connectivity, and structure of the cerebellum are also associated with dystonia, a neurological disorder characterized by abnormal and sustained muscle contractions often leading to abnormal maintained postures. In this manuscript, the authors discuss their views on how the cerebellum may play a role in dystonia. The following topics are discussed:

-

The relationships between neuronal/network dysfunctions and motor abnormalities in rodent models of dystonia.

-

Data about brain structure, cerebellar metabolism, cerebellar connections, and noninvasive cerebellar stimulation that support (or not) a role for the cerebellum in human dystonia.

-

Connections between the cerebellum and motor cortical and sub-cortical structures that could support a role for the cerebellum in dystonia.

Overall points of consensus include:

-

Neuronal dysfunction originating in the cerebellum can drive dystonic movements in rodent model systems.

-

Imaging and neurophysiological studies in humans suggest that the cerebellum plays a role in the pathophysiology of dystonia, but do not provide conclusive evidence that the cerebellum is the primary or sole neuroanatomical site of origin.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Albanese A et al. Phenomenology and classification of dystonia: a consensus update. Mov Disord. 2013;28(7):863–73.

Bhatia KP, Marsden CD. The behavioral and motor consequences of focal lesions of the basal ganglia in man. Brain. 1994;117:859–76.

Neychev VK et al. The functional neuroanatomy of dystonia. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;42(2):185–201.

Prudente CN, Hess EJ, Jinnah HA. Dystonia as a network disorder: what is the role of the cerebellum? Neuroscience. 2014;260:23–35.

Malfait N, Sanger TD. Does dystonia always include co-contraction? A study of unconstrained reaching in children with primary and secondary dystonia. Exp Brain Res. 2007;176(2):206–16.

Yanagisawa N, Goto A. Dystonia musculorum deformans. Analysis with electromyography. J Neurol Sci. 1971;13(1):39–65.

Guehl D et al. Primate models of dystonia. Prog Neurobiol. 2009;87(2):118–31.

Wilson BK, Hess EJ. Animal models for dystonia. Mov Disord. 2013;28(7):982–9.

Jinnah HA et al. Rodent models for dystonia research: characteristics, evaluation, and utility. Mov Disord. 2005;20(3):283–92.

Butler AB, Hodos W. Comparative vertebrate neuroanatomy: evolution and adaptation. 2nd ed. Hoboken, N.J: Wiley-Interscience; 2005. p. xxi–715.

Lemon RN. Descending pathways in motor control. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2008;31:195–218.

Ericsson J et al. Striatal cellular properties conserved from lampreys to mammals. J Physiol. 2011;589(Pt 12):2979–92.

Shakkottai VG. Physiologic changes associated with cerebellar dystonia. Cerebellum. 2014;13(5):637–44.

Filip P, Lungu OV, Bares M. Dystonia and the cerebellum: a new field of interest in movement disorders? Clin Neurophysiol. 2013;124(7):1269–76.

Sadnicka A et al. The cerebellum in dystonia—help or hindrance? Clin Neurophysiol. 2012;123(1):65–70.

Avanzino L, Abbruzzese G. How does the cerebellum contribute to the pathophysiology of dystonia. Basal Ganglia. 2012;2:231–5.

Zoons E et al. Structural, functional and molecular imaging of the brain in primary focal dystonia—a review. NeuroImage. 2011;56(3):1011–20.

Burke RE, Fahn S. Chlorpromazine methiodide acts at the vestibular nuclear complex to induce barrel rotation in the rat. Brain Res. 1983;288(1–2):273–81.

Cenci MA, Whishaw IQ, Schallert T. Animal models of neurological deficits: how relevant is the rat? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3(7):574–9.

Dang MT et al. Generation and characterization of Dyt1 DeltaGAG knock-in mouse as a model for early-onset dystonia. Exp Neurol. 2005;196(2):452–63.

Tanabe LM, Martin C, Dauer WT. Genetic background modulates the phenotype of a mouse model of DYT1 dystonia. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e32245.

Zhao Y, Sharma N, LeDoux MS. The DYT1 carrier state increases energy demand in the olivocerebellar network. Neuroscience. 2011;177:183–94.

Song CH et al. Subtle microstructural changes of the cerebellum in a knock-in mouse model of DYT1 dystonia. Neurobiol Dis. 2014;62:372–80.

Liang CC et al. TorsinA hypofunction causes abnormal twisting movements and sensorimotor circuit neurodegeneration. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(7):3080–92.

Weisheit, C.E. and W.T. Dauer, A novel conditional knock-in approach defines molecular and circuit effects of the DYT1 dystonia mutation. Hum Mol Genet, 2015.

Pappas SS et al. Forebrain deletion of the dystonia protein torsinA causes dystonic-like movements and loss of striatal cholinergic neurons. Elife. 2015;4:e08352.

Yokoi F et al. Motor deficits and hyperactivity in cerebral cortex-specific Dyt1 conditional knockout mice. J Biochem. 2008;143(1):39–47.

Yokoi F et al. Motor deficits and decreased striatal dopamine receptor 2 binding activity in the striatum-specific Dyt1 conditional knockout mice. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e24539.

Tanabe LM et al. Primary dystonia: molecules and mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5(11):598–609.

Middleton FA, Strick PL. Basal ganglia and cerebellar loops: motor and cognitive circuits. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2000;31(2–3):236–50.

Dum RP, Li C, Strick PL. Motor and nonmotor domains in the monkey dentate. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;978:289–301.

Akkal D, Dum RP, Strick PL. Supplementary motor area and presupplementary motor area: targets of basal ganglia and cerebellar output. J Neurosci. 2007;27(40):10659–73.

Percheron G et al. The primate motor thalamus. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1996;22(2):93–181.

Hoshi E et al. The cerebellum communicates with the basal ganglia. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(11):1491–3.

Chen CH et al. Short latency cerebellar modulation of the basal ganglia. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17(12):1767–75.

Bostan AC, Dum RP, Strick PL. The basal ganglia communicate with the cerebellum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(18):8452–6.

Kelly RM, Strick PL. Macro-architecture of basal ganglia loops with the cerebral cortex: use of rabies virus to reveal multisynaptic circuits. Prog Brain Res. 2004;143:449–59.

Sutton AC et al. Stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus engages the cerebellum for motor function in parkinsonian rats. Brain Struct Funct. 2015;220(6):3595–609.

Campbell DB, Hess EJ. Cerebellar circuitry is activated during convulsive episodes in the tottering (tg/tg) mutant mouse. Neuroscience. 1998;85(3):773–83.

Ulug AM et al. Cerebellothalamocortical pathway abnormalities in torsinA DYT1 knock-in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(16):6638–43.

Chen G et al. Low-frequency oscillations in the cerebellar cortex of the tottering mouse. J Neurophysiol. 2009;101(1):234–45.

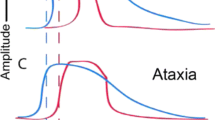

Walter JT et al. Decreases in the precision of Purkinje cell pacemaking cause cerebellar dysfunction and ataxia. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9(3):389–97.

Fremont R et al. Abnormal high-frequency burst firing of cerebellar neurons in rapid-onset dystonia-parkinsonism. J Neurosci. 2014;34(35):11723–32.

Hisatsune C et al. IP3R1 deficiency in the cerebellum/brainstem causes basal ganglia-independent dystonia by triggering tonic Purkinje cell firings in mice. Front Neural Circuits. 2013;7:156.

Campbell DB, Hess EJ. L-type calcium channels contribute to the tottering mouse dystonic episodes. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;55(1):23–31.

LeDoux MS, Lorden JF, Ervin JM. Cerebellectomy eliminates the motor syndrome of the genetically dystonic rat. Exp Neurol. 1993;120(2):302–10.

Calderon DP et al. The neural substrates of rapid-onset dystonia-parkinsonism. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14(3):357–65.

Neychev VK et al. The basal ganglia and cerebellum interact in the expression of dystonic movement. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 9):2499–509.

Raike RS, Hess EJ, Jinnah HA. Dystonia and cerebellar degeneration in the leaner mouse mutant. Brain Res. 2015;1611:56–64.

Raike RS et al. Limited regional cerebellar dysfunction induces focal dystonia in mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;49C:200–10.

Fan X et al. Selective and sustained alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor activation in cerebellum induces dystonia in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;340(3):733–41.

Pizoli CE et al. Abnormal cerebellar signaling induces dystonia in mice. J Neurosci. 2002;22(17):7825–33.

Alvarez-Fischer D et al. Prolonged generalized dystonia after chronic cerebellar application of kainic acid. Brain Res. 2012;1464:82–8.

Rose SJ et al. A new knock-in mouse model of l-DOPA-responsive dystonia. Brain. 2015;138(Pt 10):2987–3002.

Cooper IS, Upton AR. Use of chronic cerebellar stimulation for disorders of disinhibition. Lancet. 1978;1(8064):595–600.

Bradnam LV et al. Anodal transcranial direct current stimulation to the cerebellum improves handwriting and cyclic drawing kinematics in focal hand dystonia. Front Hum Neurosci. 2015;9:286.

Sokal P et al. Deep anterior cerebellar stimulation reduces symptoms of secondary dystonia in patients with cerebral palsy treated due to spasticity. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2015;135:62–8.

Eidelberg D et al. Functional brain networks in DYT1 dystonia. Ann Neurol. 1998;44(3):303–12.

Le Ber I et al. Predominant dystonia with marked cerebellar atrophy: a rare phenotype in familial dystonia. Neurology. 2006;67(10):1769–73.

Dow RS, Moruzzi G. The physiology and pathology of the cerebellum. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press ; 1958.675 p

Mottolese C et al. Mapping motor representations in the human cerebellum. Brain. 2013;136(Pt 1):330–42.

Nashold Jr BS, Slaughter DG. Effects of stimulating or destroying the deep cerebellar regions in man. J Neurosurg. 1969;31(2):172–86.

Heiney SA et al. Precise control of movement kinematics by optogenetic inhibition of Purkinje cell activity. J Neurosci. 2014;34(6):2321–30.

LeDoux MS. Animal models of dystonia: lessons from a mutant rat. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;42(2):152–61.

Xiao J, Ledoux MS. Caytaxin deficiency causes generalized dystonia in rats. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;141(2):181–92.

Fremont R, Tewari A, Khodakhah K. Aberrant Purkinje cell activity is the cause of dystonia in a shRNA-based mouse model of rapid onset dystonia-parkinsonism. Neurobiol Dis. 2015;82:200–12.

Harries AM et al. Unilateral pallidal deep brain stimulation in a patient with dystonia secondary to episodic ataxia type 2. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2013;91(4):233–5.

Hu, Y., et al., Identification of a novel nonsense mutation p.Tyr1957Ter of CACNA1A in a Chinese family with episodic ataxia 2. PLoS One, 2013. 8(2): p. e56362.

Weisz CJ et al. Potassium channel blockers inhibit the triggers of attacks in the calcium channel mouse mutant tottering. J Neurosci. 2005;25(16):4141–5.

Alvina K, Khodakhah K. The therapeutic mode of action of 4-aminopyridine in cerebellar ataxia. J Neurosci. 2010;30(21):7258–68.

Alvina K, Khodakhah K. KCa channels as therapeutic targets in episodic ataxia type-2. J Neurosci. 2010;30(21):7249–57.

Starr PA et al. Spontaneous pallidal neuronal activity in human dystonia: comparison with Parkinson's disease and normal macaque. J Neurophysiol. 2005;93(6):3165–76.

Meunier S et al. Plasticity of cortical inhibition in dystonia is impaired after motor learning and paired-associative stimulation. Eur J Neurosci. 2012;35(6):975–86.

Castrop F et al. Basal ganglia-premotor dysfunction during movement imagination in writer's cramp. Mov Disord. 2012;27(11):1432–9.

Mure H et al. Deep brain stimulation of the thalamic ventral lateral anterior nucleus for DYT6 dystonia. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2014;92(6):393–6.

Koy A et al. Young adults with dyskinetic cerebral palsy improve subjectively on pallidal stimulation, but not in formal dystonia, gait, speech and swallowing testing. Eur Neurol. 2014;72(5–6):340–8.

Volkmann J et al. Pallidal neurostimulation in patients with medication-refractory cervical dystonia: a randomised, sham-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(9):875–84.

Ozelius LJ et al. The early-onset torsion dystonia gene (DYT1) encodes an ATP-binding protein. Nat Genet. 1997;17(1):40–8.

LeDoux MS et al. Genotype-phenotype correlations in THAP1 dystonia: molecular foundations and description of new cases. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012;18(5):414–25.

Vemula SR et al. Role of Galpha(olf) in familial and sporadic adult-onset primary dystonia. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22(12):2510–9.

Zhao Y et al. Neural expression of the transcription factor THAP1 during development in rat. Neuroscience. 2013;231:282–95.

Xiao J et al. Developmental expression of rat torsinA transcript and protein. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2004;152(1):47–60.

Carbon M et al. Increased sensorimotor network activity in DYT1 dystonia: a functional imaging study. Brain. 2010;133(Pt 3):690–700.

Jinnah HA, Hess EJ. A new twist on the anatomy of dystonia: the basal ganglia and the cerebellum? Neurology. 2006;67(10):1740–1.

Perlmutter JS, Thach WT. Writer's cramp: questions of causation. Neurology. 2007;69(4):331–2.

LeDoux MS, Brady KA. Secondary cervical dystonia associated with structural lesions of the central nervous system. Mov Disord. 2003;18(1):60–9.

Waln O, LeDoux MS. Delayed-onset oromandibular dystonia after a cerebellar hemorrhagic stroke. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2010;16(9):623–5.

Prudente CN et al. Neuropathology of cervical dystonia. Exp Neurol. 2013;241:95–104.

LeDoux MS, Hurst DC, Lorden JF. Single-unit activity of cerebellar nuclear cells in the awake genetically dystonic rat. Neuroscience. 1998;86(2):533–45.

Sawada K et al. Striking pattern of Purkinje cell loss in cerebellum of an ataxic mutant mouse, tottering. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars). 2009;69(1):138–45.

Zhang L et al. Altered dendritic morphology of Purkinje cells in Dyt1 DeltaGAG knock-in and purkinje cell-specific Dyt1 conditional knockout mice. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e18357.

Hirasawa M et al. Carbonic anhydrase related protein 8 mutation results in aberrant synaptic morphology and excitatory synaptic function in the cerebellum. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007;35(1):161–70.

Xiao J, Gong S, Ledoux MS. Caytaxin deficiency disrupts signaling pathways in cerebellar cortex. Neuroscience. 2007;144(2):439–61.

Charlesworth G et al. Mutations in HPCA cause autosomal-recessive primary isolated dystonia. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;96(4):657–65.

Tzingounis AV et al. Hippocalcin gates the calcium activation of the slow afterhyperpolarization in hippocampal pyramidal cells. Neuron. 2007;53(4):487–93.

Raike RS et al. Stress, caffeine and ethanol trigger transient neurological dysfunction through shared mechanisms in a mouse calcium channelopathy. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;50:151–9.

Maejima T et al. Postnatal loss of P/Q-type channels confined to rhombic-lip-derived neurons alters synaptic transmission at the parallel fiber to purkinje cell synapse and replicates genomic Cacna1a mutation phenotype of ataxia and seizures in mice. J Neurosci. 2013;33(12):5162–74.

LeDoux MS, Lorden JF. Abnormal spontaneous and harmaline-stimulated Purkinje cell activity in the awake genetically dystonic rat. Exp Brain Res. 2002;145(4):457–67.

Argyelan M et al. Cerebellothalamocortical connectivity regulates penetrance in dystonia. J Neurosci. 2009;29(31):9740–7.

Asanuma K et al. The metabolic pathology of dopa-responsive dystonia. Ann Neurol. 2005;57(4):596–600.

Hutchinson M et al. The metabolic topography of essential blepharospasm: a focal dystonia with general implications. Neurology. 2000;55(5):673–7.

Carbon M et al. Regional metabolism in primary torsion dystonia: effects of penetrance and genotype. Neurology. 2004;62(8):1384–90.

Carbon M et al. Metabolic changes in DYT11 myoclonus-dystonia. Neurology. 2013;80(4):385–91.

Eidelberg D et al. The metabolic topography of idiopathic torsion dystonia. Brain. 1995;118(Pt 6):1473–84.

Niethammer M et al. Hereditary dystonia as a neurodevelopmental circuit disorder: evidence from neuroimaging. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;42(2):202–9.

Carbon M, Eidelberg D. Abnormal structure-function relationships in hereditary dystonia. Neuroscience. 2009;164(1):220–9.

Odergren T, Stone-Elander S, Ingvar M. Cerebral and cerebellar activation in correlation to the action-induced dystonia in writer's cramp. Mov Disord. 1998;13(3):497–508.

Carbon M et al. Impaired sequence learning in dystonia mutation carriers: a genotypic effect. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 5):1416–27.

Carbon M et al. Increased cerebellar activation during sequence learning in DYT1 carriers: an equiperformance study. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 1):146–54.

Thobois S et al. Globus pallidus stimulation reduces frontal hyperactivity in tardive dystonia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28(6):1127–38.

Delmaire C et al. Structural abnormalities in the cerebellum and sensorimotor circuit in writer's cramp. Neurology. 2007;69(4):376–80.

Carbon M et al. Microstructural white matter changes in primary torsion dystonia. Mov Disord. 2008;23(2):234–9.

Vo A et al. Thalamocortical connectivity correlates with phenotypic variability in dystonia. Cereb Cortex. 2015;25(9):3086–94.

Sako, W., et al., The visual perception of natural motion: abnormal task-related neural activity in DYT1 dystonia. Brain, 2015.

Dresel C et al. Multiple changes of functional connectivity between sensorimotor areas in focal hand dystonia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85(11):1245–52.

Draganski B et al. "Motor circuit" gray matter changes in idiopathic cervical dystonia. Neurology. 2003;61(9):1228–31.

Obermann M et al. Morphometric changes of sensorimotor structures in focal dystonia. Mov Disord. 2007;22(8):1117–23.

Ramdhani RA et al. What's special about task in dystonia? A voxel-based morphometry and diffusion weighted imaging study. Mov Disord. 2014;29(9):1141–50.

Draganski B et al. Genotype-phenotype interactions in primary dystonias revealed by differential changes in brain structure. NeuroImage. 2009;47(4):1141–7.

Zeuner KE et al. Increased volume and impaired function: the role of the basal ganglia in writer's cramp. Brain Behav. 2015;5(2):e00301.

Baker RS et al. A functional magnetic resonance imaging study in patients with benign essential blepharospasm. J Neuroophthalmol. 2003;23(1):11–5.

Schmidt KE et al. Striatal activation during blepharospasm revealed by fMRI. Neurology. 2003;60(11):1738–43.

Zhou B et al. A resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging study of patients with benign essential blepharospasm. J Neuroophthalmol. 2013;33(3):235–40.

Hu XY et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging study of writer's cramp. Chin Med J. 2006;119(15):1263–71.

Gallea C et al. Increased cortico-striatal connectivity during motor practice contributes to the consolidation of motor memory in writer's cramp patients. Neuroimage Clin. 2015;8:180–92.

Fiorio M et al. The role of the cerebellum in dynamic changes of the sense of body ownership: a study in patients with cerebellar degeneration. J Cogn Neurosci. 2014;26(4):712–21.

Moore RD et al. Individuated finger control in focal hand dystonia: an fMRI study. NeuroImage. 2012;61(4):823–31.

Delnooz CC et al. Task-free functional MRI in cervical dystonia reveals multi-network changes that partially normalize with botulinum toxin. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e62877.

Mohammadi B et al. Changes in resting-state brain networks in writer's cramp. Hum Brain Mapp. 2012;33(4):840–8.

Lehericy S et al. The anatomical basis of dystonia: current view using neuroimaging. Mov Disord. 2013;28(7):944–57.

Popa T et al. Cerebellar processing of sensory inputs primes motor cortex plasticity. Cereb Cortex. 2013;23(2):305–14.

Hubsch C et al. Defective cerebellar control of cortical plasticity in writer's cramp. Brain. 2013;136(Pt 7):2050–62.

Bostan AC, Strick PL. The cerebellum and basal ganglia are interconnected. Neuropsychol Rev. 2010;20(3):261–70.

Bostan AC, Dum RP, Strick PL. Cerebellar networks with the cerebral cortex and basal ganglia. Trends Cogn Sci. 2013;17(5):241–54.

Quartarone A, Hallett M. Emerging concepts in the physiological basis of dystonia. Mov Disord. 2013;28(7):958–67.

Blakemore SJ, Wolpert DM, Frith CD. The cerebellum contributes to somatosensory cortical activity during self-produced tactile stimulation. NeuroImage. 1999;10(4):448–59.

Stoodley CJ, Schmahmann JD. Evidence for topographic organization in the cerebellum of motor control versus cognitive and affective processing. Cortex. 2010;46(7):831–44.

Batla, A., et al., The role of cerebellum in patients with late onset cervical/segmental dystonia?-Evidence from the clinic. Parkinsonism Relat Disord, 2015.

Cancel G et al. Molecular and clinical correlations in spinocerebellar ataxia 2: a study of 32 families. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6(5):709–15.

Hagenah JM et al. Focal dystonia as a presenting sign of spinocerebellar ataxia 17. Mov Disord. 2004;19(2):217–20.

Lang AE et al. Homozygous inheritance of the Machado-Joseph disease gene. Ann Neurol. 1994;36(3):443–7.

van de Warrenburg BP et al. The syndrome of (predominantly cervical) dystonia and cerebellar ataxia: new cases indicate a distinct but heterogeneous entity. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78(7):774–5.

Kuoppamaki M et al. Slowly progressive cerebellar ataxia and cervical dystonia: clinical presentation of a new form of spinocerebellar ataxia? Mov Disord. 2003;18(2):200–6.

Kumandas S et al. Torticollis secondary to posterior fossa and cervical spinal cord tumors: report of five cases and literature review. Neurosurg Rev. 2006;29(4):333–8 discussion 338.

Teo JT et al. Neurophysiological evidence for cerebellar dysfunction in primary focal dystonia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80(1):80–3.

Sommer M et al. Learning in Parkinson's disease: eyeblink conditioning, declarative learning, and procedural learning. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;67(1):27–34.

Paudel R et al. Neuropathological features of genetically confirmed DYT1 dystonia: investigating disease-specific inclusions. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2014;2:159.

Kulisevsky J et al. Meige syndrome: neuropathology of a case. Mov Disord. 1988;3(2):170–5.

Paudel R et al. Review: genetics and neuropathology of primary pure dystonia. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2012;38(6):520–34.

Iwata NK, Ugawa Y. The effects of cerebellar stimulation on the motor cortical excitability in neurological disorders: a review. Cerebellum. 2005;4(4):218–23.

Brighina F et al. Effects of cerebellar TMS on motor cortex of patients with focal dystonia: a preliminary report. Exp Brain Res. 2009;192(4):651–6.

Koch G et al. Effects of two weeks of cerebellar theta burst stimulation in cervical dystonia patients. Brain Stimul. 2014;7(4):564–72.

Hamada M et al. Cerebellar modulation of human associative plasticity. J Physiol. 2012;590(Pt 10):2365–74.

Sadnicka A et al. Cerebellar stimulation fails to modulate motor cortex plasticity in writing dystonia. Mov Disord. 2014;29(10):1304–7.

Hubsch C et al. Impaired saccadic adaptation in DYT11 dystonia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82(10):1103–6.

Hoffland BS et al. Cerebellum-dependent associative learning deficits in primary dystonia are normalized by rTMS and practice. Eur J Neurosci. 2013;38(1):2166–71.

Hoffland BS et al. Cerebellar theta burst stimulation impairs eyeblink classical conditioning. J Physiol. 2012;590(Pt 4):887–97.

Linssen MW et al. A single session of cerebellar theta burst stimulation does not alter writing performance in writer's cramp. Brain. 2015;138(Pt 6):e355.

Acknowledgments

VGS was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (K08NS072158, R01NS085054). EJH was supported in part by Public Health Service grant R01 NS088528 and a grant from the United States Department of Defense (PR140091). MSL was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 NS069936, R01 NS082296, and Dystonia Coalition U54 NS065701), the Dorothy/Daniel Gerwin Parkinson’s Research Fund, and the Benign Essential Blepharospasm Research Foundation. HAJ was supported in part by a grant to the Dystonia Coalition (U54 NS065701, TR001456) from the Office of Rare Diseases at the National Center for Advancing Translational Studies and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke at the NIH. MH was supported by the NIH intramural program. PLS was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 NS24328, P30 NS076405, P40 OD010996). KK was supported by NIH grants NS050808 and NS079750.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shakkottai, V.G., Batla, A., Bhatia, K. et al. Current Opinions and Areas of Consensus on the Role of the Cerebellum in Dystonia. Cerebellum 16, 577–594 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-016-0825-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-016-0825-6