Abstract

Fridays for Future has risen as a new environmental movement pushing politicians to take action against climate change. However, its interaction with other political actors, most importantly political parties, has hardly been addressed systematically by scientific research. In this article, we take stock of party reactions to the movement on the national and subnational level in Germany. Furthermore, we investigate possible explanations for variances in these reactions in a comparison of subnational party organisations and thereby, focus on dynamics of party competition, especially on the impact of the Green Party as established contender and of the populist radical right AfD and its new role in environmental politics. We show that party reactions to the movement vary widely reflecting a clear divide on the left-right-spectrum. While centre-left parties, particularly the Green Party, support the movement, centre-right parties are utmost cautious and the populist radical right AfD stands out with a blatantly hostile attitude. Though indications for the impact of party competition dynamics were minor, we observed a strong polarisation on the climate issue that may take effect in the near future.

Zusammenfassung

Die Schülerproteste von Fridays for Future haben sich zu einer neuen Umweltbewegung entwickelt, welche Politiker*innen zu konsequenten Maßnahmen gegen die Erderwärmung auffordert. Trotz dieser direkten Adressierung ist die Interaktion zwischen Bewegung und politischen Akteuren – vor allem politische Parteien – bislang kaum Gegenstand systematischer wissenschaftlicher Untersuchungen. Hier setzen die beiden Hauptziele des Artikels an: erstens, wird für Deutschland, auf Bundes- wie Länderebene, eine erste Bilanz über die Reaktionen der Parteien auf die Bewegung gezogen; und zweitens, werden unter spezieller Berücksichtigung des Parteienwettbewerbs mögliche Erklärungen für die Varianz zwischen diesen Reaktionen diskutiert. Insbesondere der Einfluss rechtspopulistischer Parteien und deren neue Rolle in der Umweltpolitik sind dabei interessant.

Zentrale Ergebnisse sind, dass die Reaktionen der einzelnen Parteien stark untereinander variieren und dabei das traditionelle Links-Rechts-Spektrum widerspiegeln. Während Mitte-Links Parteien, vor allem Bündnis’90/Die Grünen, der Bewegung sehr unterstützend gegenüberstehen, verhalten sich die Mitte-Rechts-Parteien sehr zurückhaltend und die rechtspopulistische AfD sticht mit einer offen feindlichen Haltung heraus. Obwohl die Ergebnisse auf einen Einfluss des Parteienwettbewerbs nur hinweisen können, ist eine starke Polarisierung in der klimapolitischen Debatte zu konstatieren, welche in naher Zukunft eine Wirkung entfalten kann.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Since 2018, Fridays for Future (FfF) has risen as a new environmental movement pushing politicians to take action against climate change. So far, research has mainly looked from a sociological perspective at this movement and provided insights into the socio-structural composition of the protesters and into their personal motives for participation (Wahlström et al. 2019; De Moor et al. 2020)Footnote 1. Its reception in the political sphere, in particular by political parties as its main actors, however, has hardly been subject of systematic examination yet although research showed this relationship to be essential for understanding the effects of social movements (Rucht 1996; Keman 2006; Tarrow 2011). While Sommer et al. (2019) only gave a short and cursory overview on political reactions to FfF, Raisch and Zohlnhöfer (2020) presented first results for German federal parties based on the analysis of Twitter accounts. This paper intends to expand on this research by capturing party reactions comprehensively based on a variety of sources, including both social media and parliamentary debates, and exploring possible explanations for variation in party reactions in a comparative manner. We perceive Germany as a suitable site of investigation for two reasons: it represents one of the most important areas for FfF in Europe regarding their absolute numbers (Wahlström et al. 2019; De Moor et al. 2020); and its federal structure offers a promising opportunity to harness the virtues of comparison. We proceed in two steps. First, we take stock of how different parties meet the FfF-movement and classify their reactions on two dimensions which indicate the basic position of the party towards the movement and the attention a party concedes to it: degree of approval and frequency of reference. Importantly, we conceive FfF not as a contender of parties in the intermediary system but as an object of party competitionFootnote 2. Second, in order to provide a comprehensive view on party reactions to the new movement, we shift attention to possible explanations for the variance of reactions. For this purpose, we draw upon existing research (e.g. Hutter and Vliegenthart 2018) identifying factors responsible for how parties react to social movements. In particular, we focus on the ideological affiliation of parties and aspects of party competition. For the latter, we attribute a special role to the German Green Party and the populist radical right party (PRRP)Footnote 3Alternative für Deutschland (Alternative for Germany, AfD) and aim to explore their impact on party reactions overall. While an effect of green parties in the field of environmental policy is already an established subject of political science research, the latter only recently receives some more attention. Thus, understanding both parties as central factors in our analysis, in the wake of rising PRRP influence, we intend, in particular, to move the AfD to the limelight and examine its possible impact.

In sum, this paper addresses two key research questions:

-

1.

How do individual political parties in Germany react to the Fridays for Future movement regarding the degree of approval as well as the frequency of reference?

-

2.

Which factors may account for the variance in reactions of the parties particularly focussing on party competition?

To respond to these questions we, first, outline theoretical considerations on party behaviour and social movements and extract potential causal factors for different party reactions. Next, we introduce our research design and methods and, on this basis, give an account of our descriptive and comparative analyses. The final section discusses our key findings and contributions.

2 Theoretical considerations

Research has been interested in environmental movements since the beginning of environmental politics in the 1970s and analysed both their emergence and impact. For instance, Müller-Rommel (1993) showed an influence on the development of Green parties and more recently, Jahn (2017) confirmed an effect on governmental positions and even environmental outcomes. Importantly, Rucht (1996) points to the necessity to investigate the responsiveness of political parties to (environmental) movements in order to understand their impact in the political sphere (also Piccio 2019).

To address this latter point, we first have to clarify the relation of political parties and social movements in general. According to the literature, social movements might either merge with or into a political party and thus transfer their demands to the parliamentary sphere, or deliberately stay outside the parliamentary policy-making process and seek to take effect first and foremost through agenda-setting (Hutter et al. 2019). The latter is the very strategy that FfF has declared to pursue, so far (see FfF 2020; Haunss et al. 2019; Neuber and Gardner 2020). This non-partisan attitude, however, does not mean that FfF operates without any link to political parties. In fact, parties represent their main target group since—in accordance with partisan theory—these are ultimately responsible to translate its demands into political action (Keman 2006). Hence, like movements in general, FfF seeks support among political parties to render their agenda-setting efforts effective not only within civil society but also inside parliament (Dryzek et al. 2003; Hutter et al. 2019). Conversely, assuming parties to behave rationally, different reactions to FfF might emerge due to varying strategic considerations by parties in terms of vote- and office-seeking (Downs 1957; Strøm 1990; Poguntke 2006).

Party reactions to protests or movements, in general, have rarely been a specific subject to research (e.g. Tarrow 2011; as exception Piccio 2019). Only recently, Hutter and Vliegenthart (2018) investigated the responsivity of individual political parties to issues brought forward by street protests in four Western European countriesFootnote 4. Although we focus on reactions to the movement itself, FfF is strongly intertwined with its demands, so that we may utilise the set of factors suggested by Hutter and Vliegenthart (2018) to approach our second research question and explain the variety of party responses. Thus, we first focus on ideological affiliation on the traditional left-right-scale and expect left parties to take rather positive positions towards FfF while right parties tend to be more opposing. Generally speaking, this is also in accordance with the literature on party positions on environmental policy although the exact positioning of (in particular centre-left and centre-right) parties remains a question at issue (Carter 2013; Töller 2017). In contrast, the extreme poles, usually, are more clear-cut. Turning to the German case, they are represented by the Green Party (positive) and the populist radical right AfD (negative) (Neuber and Gharrity Gardner 2020). The Green Party integrates two further aspects considered by Hutter and Vliegenthart (2018), as it can be seen to be most radical on climate matters and in any case, to hold the issue ownership on this policy (Spoon et al. 2014). Although issue ownership is attributed to a party through the electorate, literature confirms that parties themselves take actively part in maintaining and pushing this reputation (e.g. Budge 2015). Furthermore, the Greens originated in the environmental movement and traditionally are affiliated with other actors advocating for environmental policy (Dryzek et al. 2003; Bukow 2016), so that, all in all, they can be expected to support FfF most positively and vigorously.

However, literature states quite unanimously that individual parties might deviate from the reactions typical to their ideological affiliation depending on whether they are part of the government coalition or part of the opposition (Vliegenthart et al. 2011; Green-Pedersen and Mortensen 2010; Van der Brug and Berkhout 2015). Even though the direction of effect is less unambiguous, we take possible effects of government-opposition status into account and in accordance with Hutter and Vliegenthart (2018) conjecture opposition parties to react more frequently on FfF since they offer an opportunity to criticise the government (also Gilljam et al. 2012).

When it comes to the ‘contagion effect’ of parties we diverge from Hutter’s and Vliegenthart’s idea that parties show reaction to the movement after it was picked up by “some parties” (2018). For pragmatic reasons we neglect this dimension of time but refine the focus on party competition by using the concepts of electoral threat and opportunity, put forward by Spoon et al. (2014). While the authors provide a number of factors, for our comparison we concentrate on the potential electoral threat of the contender parties and its ideological proximity to the respective responding parties. Thus, we seek to provide an explanation for variance while at the same time keeping the analysis manageable. Since we are looking at reactions to an environmental movement the Green Party seems to be the obvious candidate for the role of the main contender. However, as described above, in the wake of recent political trends PRRP, such as the AfD, appear to have become increasingly influential regarding the issue competition in Western European party systems (e.g. Meguid 2005; Bale et al. 2010; Abou-Chadi and Krause 2020)Footnote 5. In terms of environmental policy, they clearly have marked a change of party competition as they broke the political consensus on this former valence issue and (in their majority) take a firmly negative stance (Gemenis et al. 2012; Schaller and Carius 2019; Lockwood 2018). Consequently, from a theoretical perspective we would assume both the Green Party and the AfD to pressure mainstream parties (meaning above all CDU/CSU and SPD) in the field of environmental policy. To sum up, we derive the following assumptions as heuristic landmarks guiding our investigation (Table 1).

3 Research design and methods

Our research is guided by two questions. To answer the first one, we start with parties on the federal level and analyse their reactions to FfF. We deem this step important for three reasons: first, since FfF has addressed all levels of politics, neglecting the highest administrative level would seem to miss the mark of comprehensively investigating party reactions to FfF in Germany. Second, we are thus able to cross-validate our findings from the Länder-level on an enriched data basis. In addition, we use the positioning of federal parties as a yardstick to evaluate varying responses to FfF on the subnational level. Overall, research points to the dynamics between levels which we reflect in our two-step approach (Bräuninger et al. 2020).

For our second research question, we turn to the Länder-level as this enables us to leave a simple single-case study behind and explore potential causes of variance between German political partiesFootnote 6 more precisely in a structured comparative analysis (Beinborn et al. 2018). Thereby comparing parties from German Länder ensures extensive similarities that let us hold several potentially influencing factors quite constant (Sack and Töller 2018)—of which literature on party competition deems the electoral system and political salience of FfF most important (Spoon et al. 2014). Thus, following a classic most similar systems design (e.g. Berg-Schlosser and De Meur 2009), we are equally interested in maximising the variance on our four factors derived in the previous section (e.g. Peters 2013): party ideology, issue ownership, government-opposition status and especially, the specific constellation of party competition.

Since variance of party ideology is almost guaranteed in German multi-party systems and environmental issue ownership is almost exclusively aligned with the Green Party, we focus on increasing the variance of the other two factors choosing parties from Länder which differ distinctively in terms of their governmental compositions and their party competition constellationsFootnote 7 (Bräuninger et al. 2020). As delineated above, for the latter we expect the Green Party and the AfD to be most decisive and therefore look at their respective strength. Hence, our case selection comprises an intermediate n with 37 parties in six German LänderFootnote 8 selected on two criteria (Table 2).

With the six complementary cases on the federal level, these parties stand for the population of the relevant parties in the German federal system.

To analyse these parties’ reactions to FfF we discover two dimensions: the degree of approval as well as the frequency of reference. Captivating the degree of approval, we adapt existing research that focuses general party reactions to (new) contenders (Meguid 2005), e.g. accommodation, dismissal, aversion, and strategies of dealing with contenders (Bale et al. 2010). Following the literature, we differentiate between five forms of reaction which allow us to identify qualitative differences within general rejection or approval: strong and weak rejection, caution, strong and weak affirmation (Table 3). In a first inductive step, we applied the categories to the material (see below) and developed a coding scheme which we re-assessed and refined before coding all dataFootnote 9. Overall, the coding scheme proved applicable and left only a small amount of ambiguous coding segmentsFootnote 10 which were crosschecked in the research team for intercoder-reliability. Differentiating between weak and strong responses enables us to indicate qualitative differences, e.g. between a critical and defamatory stance. To assess overall party positions, we estimated average position based on all coded data.

Measuring the frequency of reference is based on the notion of topic salience (Wagner and Meyer 2014). While we do not compare references to FfF with references to other topics, we follow previous research stressing the advantages of an integrative conception of salience-related and ideological features of party reaction (Meguid 2005; Guinaudeau and Persico 2014). Hence, we understand a more frequent dealing with the topic to signal parties’ interest and importance assigned to the issue.

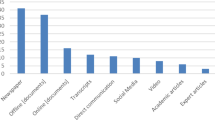

Since the FfF movement is a rather recent phenomenon we rely on a variety of data sources to raise the number of observations to a sufficient level and get a picture as complete as possible. Therefore, we assess party positions based on press releases, Twitter posts and documents of the parliamentary process on both administrative levels. While research on party preferences usually relies on manifestos (Eder et al. 2017) we cannot use this data since there was no general election after 2017 in Germany and state elections in just a few Länder. Research shows parties’ press releases to represent their position and signal their issue priorities (Harris et al. 2005). Furthermore, Twitter has become a major outlet for party communication (Jungherr 2016; Conway et al. 2015) and parliamentary documents, such as parliamentary protocols, are commonly used to assess party positions on certain issues (e.g. Maatsch 2014). Thus, we collected press releases of parties, Twitter posts and analysed parliamentary debate protocols, enquiries and motions. To be included, the respective sources had to refer explicitly to FfF or Greta Thunberg. While for parliamentary sources we coded statements irrespective of the politician’s status in the party, for the other we focused on party leaders and party’s central offices. Additionally, we considered media coverage (researched via LexisNexis) to enrich the data base. Overall, 612 observationsFootnote 11 are included in our analysis covering a time period between 08/2018 (when Greta Thunberg first demonstrated in Stockholm) and 12/2019.

4 Party reactions to Fridays for Future

In our first descriptive step, we focus on parties on the federal level to analyse their reactions to FfF and provide a comprehensive picture of German parties’ general responses. Following our research design, we differentiate between strong and weak rejection, caution, weak and strong affirmation. Overall, parties on average refer to the movement 40 times, with the AfD and Greens marking the most active parties (Fig. 1).

Here, the analysis of party positions towards the FfF movement shows three results. First, there is clear difference in party reactions to FfF along a left-right divide with centre-left parties being more supportive than conservative and liberal ones and the AfD taking a dismissive stance towards FfF. Second, conservative and liberal parties in Germany are more cautious with regard to their reaction and less explicit in their position. Third, our analysis shows a distinct polarisation between the centre-left parties and the AfD. The Green Party vigorously refers to the movement and positions itself as its principal supporter. The AfD is not only the most hostile party, it also most frequently refers to FfF. This reaction can clearly be characterised as a strong rejection of the movement and its claims. In several instances party representatives dismiss and defame the movement, question its goals and overall dispute climate change. Thus, not only the clear rejection of FfF but also the explicit reaction to the movement differentiates the party from conservative parties in Germany.

Moving to the subnational level (Fig. 2), values of approval cover the whole scale from −2 to 2, while the frequency of references to FfF ranges from zero, e.g. FDP in SNFootnote 12, to a maximum of 28 references, e.g. Greens in BY, and discloses an average of about nine references.

Overall, the analysis of the sub-national level confirms a pattern detected at the national level. Parties of the left have addressed FfF across the board positively with no party showing a value below two. Hence, they support the movement without exception. However, looking at frequency, there is variance observable with parties mentioning the movement between 2 and 28 times. Two aspects are worth mentioning: for the Left Party, we see a quite clear divide between less active Western and more vigorous Eastern associations of which the latter even outperform the corresponding Green Parties. For the Green Party, it appears to be the contrary as the regional associations of BW and BY are dominant in claiming affiliation with FfF while in the Eastern Länder their ambitions are expressed less clearly or even must be seen to be limited as in SN. In SH, on the other hand, the co-ruling Green Party and the oppositional SPD show a similarly welcoming behaviour.

In the conservative camp, all regional associations of the centre-right parties CDU, CSU, FDP and FW reluctantly address the movement and show a below-average number of references. This cautiousness is also reflected in their degree of approval as the centre-right parties notably concentrate in the middle with only two deviations to more positive positions (+1, CDU, FDP in SH) and one deviant case to the negative side (−1 CDU in ST). Additionally, three regional associations of the FPD did not yield any observations (MV, SN, ST) neither in parliament nor in press releases or on Twitter. While the parliamentary inactivity is no surprise due to their extra-parliamentary status in the concerned states, the overall reserve stands out since there are examples of parties not represented in parliament which show reactions on other channels, e.g. Green Party in MV or Left Party in BW.

All regional associations of the AfD considered in our analysis take up a clearly negative position, with blatantly hostile reactions in four cases and a slightly less rejective reaction in BW (−1.5) and SH (−1). In terms of frequency, all six regional associations are eager to bring up references to FfF noticeably often. In fact, the AfD in ST is the party in our selection that made second most references and is only excelled by the Bavarian Green Party.

Concluding, parties’ reactions are most similar within party organisations across the different regional settings, however, they still reveal variance in particular regarding the frequency of responses. Both the different degrees of activity among regional Green Parties and Left Parties as well as two aspects concerning the centre-right, namely their rather positive orientation in SH and the deviating case of the CDU in ST, are interesting in this regard and we will come back to them in the next section. While a too fine-grained examination of the variance among the regional parties could be premature concerning our rather low number of observations available for each state, general patterns are clearly discernible and in sum, they resonate with our findings from the federal level. Considering the degree of approval and the frequency of references, the AfD and the centre-left parties react most vigorously to FfF taking up two totally opposing positions. This reflects a strong polarisation on the movement while the centre-right parties remain somewhere in between.

5 A closer look at different party reactions

In this section we reflect upon our assumptions and discuss different party reactions in detail. While Social Democrats, Left and Green Party take the most positive stance towards FfF, CDU/CSU, FDP and FW are rather cautious and the AfD dismisses the movement. The frequency of reference, by and large, completes this picture and confirms the cautious attitude of the centre-right parties towards FfF as well as the positive responses of centre-left and left parties. Thus, ideological affiliation can help explain party reactions to FfF. However, we find differences between the parties that remain unexplained by the left-right scale (see above).

Therefore, we turn to other explanatory factors. First, we consider the government or opposition status of a party and assume opposition parties to react more frequently to FfF with the kind of reaction depending on ideological affiliations. On the federal level, opposition status indeed aligns with parties’ vigorousness in responding to FfF. However, looking at the subnational cases, the explanatory power of party status is limited. Due to our case selection and research focus we cannot draw conclusions for Christian Democratic parties (always a member of government in our cases) or the Left and AfD (both always in opposition). The Greens and SPD show variance in party status but this does not align with party reactions to FfF. For instance, the Greens in BW are among the most active parties in our sample despite their status as leading governmental party and more frequently refer to FfF than the oppositional SPD. And in MV, the governing SPD is more frequently referring to FfF than the oppositional Left party and the Greens, which are not in parliament. Overall, a party’s status does not explain reactions to FfF in our cases. Looking at Greens and SPD, we find strongly affirmative and highly frequent references from the parties both while in government (Green Party BW; SPD MV) and in opposition (Green Party BY; SPD SH)Footnote 13.

To arrive at a more complete picture, we turn to issue ownership. We assume issue ownership as a given condition—in our case, the German Greens are clearly owning environmental and climate issues and should thus be the party most supportive of the movement (see Sect. 2). Generally, the results of our analysis underline the role of issue ownership. All regional branches of the Green Party are clearly affirmative of FfF and refer to it above average (except for the Green Party in SN). Yet, also some other regional parties of the centre-left camp refer to FfF clearly above average, e.g. SPD in MV or SH or the Left Party in ST and SN.

Thus, while ideological affiliation and issue ownership can explain general patterns, some cases need a closer inspection. Therefore, we turn to aspects of party competition. We assumed the strength of the Greens and the AfD to impact mainstream parties’ reactions (see Table 1). While the Green Party is commonly understood as contender on climate issues (Van Haute 2016), we argue that with its described consensus-breaking course, the AfD equally must be seen as clear contender which potentially exerts influence on other parties’ climate policy positions. In accordance with the literature, we would expect contagiousness to increase with ideological proximity so that centre-left parties are more likely to be influenced by the Green Party while centre-right parties might be geared to the PRRP (Meguid 2005). Likewise, (centre-)left parties also might address similar constituencies as PRRP and, therefore, restrain their positive positions on climate issues (Bale et al. 2010). However, only a few cases align with our expectations (Table 4) indicating that party stances are consistent and only rarely change because of party competition.

The SPD does not deviate from the average reaction to FfF. Only in SH, where the Greens are an important contender, they react more frequently to FfF. In ST, where the AfD has gained a stronghold, they refer slightly below average of all regional Social Democratic parties included. However, contrary to our assumption, the SPD in SN and MV refers more frequently to FfF than on average. We argue, that this is related to the rather weak position of the local Green Party, thus giving the SPD room to actively address environmental topics.

The Christian Democratic parties deviate in two states from the party’s average position in line with our assumption. In SH the CDU is more affirmative about FfF while being confronted with a comparatively weak AfD and an over the period of investigation increasingly strong Green Party which, moreover, is their coalition partner. In ST, on the other hand, despite also sharing office with the Green Party, the CDU faces a consistently very strong AfD and a relatively small Green Party and takes a comparatively negative view on FfF.

These two cases deserve closer examination. Without being able to present in-depth case studies of the parties in the two Länder, a closer look at the political situations indicates possible reasons for the different values achieved. If we take our basic idea of the ideological distribution on FfF with the Green Party and the AfD at its extreme ends as a starting point, the dynamics of party competition point to opposite directions in the two cases. While in SH the Green Party made significant gainsFootnote 14 and the AfD more or less stagnated, in ST the AfD has performed successfully in several elections and holds its historical results from 2016 at around 25% and the Green Party only plays a minor role although in the period of investigation it doubled its support in polls up to around 11% (Holtmann and Völkl 2016). At the same time, in both states the CDU suffered serious losses in the EU election and also in other election polls. As a consequence, the Christian Democrats face serious electoral threats in both Länder with the only difference that these threats come from absolutely different directions regarding the environmental question, and thereby FfF. This line of argumentation, furthermore, is supported by a closer glance at the present coalitions. In SH the so-called Jamaica-coalition of CDU, Green Party and FDP is said to operate well and pragmatically on a basis of mutual trust and respect (Knelangen 2018). In clear contrast, the CDU-SPD-Greens coalition in ST, by default appears to work on the brink of break-up and periodically discloses diverging positions on central issues as well as a serious lack of mutual trust (Spiegel 2020). Given these dynamics of competition, in comparison the CDU in ST is more likely to direct its attention towards the AfD both in terms of vote- and office-seeking. Thus, considering these two cases and our brief analysis, we want to stress the potential of state-specific party competition as an explanation for varying responses to FfF.

6 Discussion & Conclusion

In this article we shed some light on party reactions to the Fridays for Future movement. Our first question addressed the overall reaction of parties regarding the degree of approval (i.e. affirmation or rejection) as well as the frequency of references. Initially, we looked at the federal level to approach the general positions of German parties and developed a yardstick for capturing varieties. However, our main emphasis was on the comparative analysis of reactions on the subnational level, where we in particular focused the impact of the AfD and the Greens on mainstream parties (CDU/CSU, SPD). Altogether, the analysis shows a clear difference between centre-left, centre-right and populist radical right parties. While the first group is strongly affirmative and clearly a friend of FfF, the AfD acts its part as a foe. In contrast, the centre-right parties are cautious and, mainly, keep a low profile in this polarisation. By using a fine-grained analytical approach, we were able to not only differentiate between approval or dismissal but to also uncover nuanced differences (cf. Raisch and Zohlnhöfer 2020). For instance, there is clear qualitative difference between critical reactions to FfF (e.g. from the CDU) and degrading responses by the AfDFootnote 15. In our investigation, the described general trend has to be put into perspective regarding the Länder-level. There are some differences among parties’ regional organisations, i.e. the Greens are not in all cases the most frequent supporters of FfF. This underscores the point that, at least concerning FfF, they represent no lonely extreme pole on the left. On the other side of the party landscape, it became clear that centre-right parties are consistently cautious apart from two deviant cases: In SH the CDU is more supportive, while the CDU in ST is rejecting FfF. To provide some explanations for these varieties, we followed existing research (e.g. Hutter and Vliegenthart 2018) and took party status, party ideology, as well as issue ownership and party competition into account.

Thus, answering our second question, we come back to our assumptions. While party status could not explain varieties in the six Länder, overall, party ideology is the main explanation for responses to FfF, and competition can shed light on some deviating cases. For instance, the SPD refers more frequently to FfF in states where the Greens are in less competitive positions (e.g. low number of members, smallest faction or not even in parliament). Thus, Social Democrats fill the void and are more active in supporting FfF. Nevertheless, our analysis indicates the Green Party to be the prime supporter of the movement. When it comes to the centre-right parties, regionally specific party competition constellations shaped by the Green Party resp. the AfD provide explanations for the divergent party positions in ST and SH.

Furthermore, our analysis underscores that the AfD understands climate change as a crucial issue which it addresses by combining an openly rejective attitude with a high frequency of references (Kemmerzell and Selk 2020). The latter attests a willingness to bring and keep the topic on the political agenda and, indeed, the AfD has declared the climate issue as their third main topic after Euro and migration policy (Welt 2019). Unlike other parties of the right, the AfD underlined its status as a political pariah and broke the minimal consensus on climate policy by questioning its very (scientific) legitimation. Thus, the party chose a strategy of ‘offence is the best defence’ and picked out FfF and their main activists as most prominent examples of a distinct pro-climate advocacy to prove their oppositional attitude. As Wagner (2012) has shown, a vote-maximising perspective can explain why parties emphasise issues. In our cases, the AfD seems to stress its extreme position to underline its anti-establishment position and to differentiate itself from other parties in an environment of increasing party competition around climate issues—which was fuelled from the FfF protests.

In sum, our analysis clarified a number of factors and their explanatory power for different reactions to FfF. Yet, some external variance regularly remains and we cannot rule out other (additional) explaining factors, e.g. traditional idiosyncrasies of regional party associations (Bräuninger et al. 2020), a bias caused by overrepresenting individual politicians’ statements or increased cross-party awareness caused by a different climate change exposition as it is plausible in SH due to its specific geographical situation at the coast (Böcher and Töller 2016). Thus, further state-level factors should be considered in future research. With regard to general party positions and issue ownership we adopted positions from the federal level. However, as Bräuninger et al. (2020) show, subnational party systems and party positions differ between states as well as over time. Future research might dive deeper into (environmental) policy positions on the state level. Furthermore, we conceptualised FfF as an issue parties react to. This helped to show general reaction and party stances. Yet, how and whether political parties in Germany adopt the movement’s demands and interact with FfF must be dealt with in further research.

Overall, while Fridays for Future has undoubtedly pushed environmental and climate policy discussion, systematic findings regarding party reactions to FfF have been scarce. By investigating these reactions in Germany and more specifically in six states we developed two core insights. First, our analysis presents first reliable data on the reactions of political parties to FfF at the German federal and state level. It shows a clear difference based on parties’ general ideological positions. This corroborates the existence of a partisan effect for this specific issue in Germany and, thus, let us contribute to clarify which side Social Democratic (clear affirmation) as well as Christian Democratic parties (cautiousness) are on in the field of environmental policy. Second, the fierce reactions of the AfD indicate an intense polarisation on climate policy between the centre-left and the radical right with the centre-right parties somehow in between. This raises questions whether future environmental resp. climate policy will be characterised by a bipolar (Thomeczek et al. 2019) or rather tripolar party competition. As the AfD takes a contender position in climate policy challenging the overall consensus of parties in Germany, this underlines the uneasy relation between environmentalism and right-wing populism.

Notes

While this neglects the active role FfF plays in a dynamic political discussion it helps us to investigate party stances towards the movement.

Based on Mudde’s (2017) established conceptualisation we, henceforth, refer to respective parties as populist radical right parties (PRRP). Though disagreeing on the specific term, in the face of last years’ programmatic shifts, today, political scientists agree on classifying the AfD as PRRP (e.g. Arzheimer and Berning 2019).

They focus ideological affinity, radicalism, issue ownership, opposition status and contagion effect (Hutter and Vliegenthart 2018).

Although other scholars stress that any further impact of populist radical right parties still needs to be empirically proven (e.g. Mudde 2013).

CDU, CSU: Christian democratic; FDP: liberal; FW: conservative; Green Party: green-left; SPD: social democratic; Left Party: socialist-Left; AfD: populist radical right (for details see Decker and Neu 2018).

Note that despite being a system feature, competition constellations deploy an immediate effect on individual parties by shaping their strategic behaviour in terms of office- and vote-seeking.

The selection of three governments with participation of the Green Party is not biased in Germany, since the it participates in 10 of 16 regional governments.

Coding done with MAXQDA.

As segments we conceived whole statements (i.e. a tweet or a parliamentary speech) and coded them accordingly.

Observations were derived from overall 542 sources: 97 parliamentary protocols, 97 parliamentary inquiries and motions, 93 press releases, 10 media coverages, 245 Twitter posts.

For state abbreviations see Table 2.

However, we did not focus party status in our case selection, e.g. the AfD is in opposition in all states. Thus, this insight should be investigated further.

Due to the lack of available election polls for the subnational level, we included results of the European election as a benchmark. From 12.9%, 2017 to 26% in the beginning of 2020 in election polls and in the European election the Green Party even outperformed the CDU and became strongest with 29.1% (Sources: wahlrecht.de; https://www.bundeswahlleiter.de/europawahlen/2019/ergebnisse/bund-99/land-1.html, accessed April 14 2020).

Raisch and Zohlnhöfer (2020) arrive at a slightly different picture regarding the AfD. All in all, this indicates the need for further research into party responses to FfF.

References

Abou-Chadi, Tarik, and Werner Krause. 2020. The causal effect of radical right success on mainstream parties’ policy positions: a regression discontinuity approach. British Journal of Political Science 50(3):829–847. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123418000029.

Arzheimer, Kai, and Carl C. Berning. 2019. How the Alternative for Germany (AfD) and their voters veered to the radical right, 2013–2017. Electoral Studieshttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2019.04.004.

Bale, Tim, Christoffer Green-Pedersen, André A. Krouwel, Kurt Richard Luther, and Nick Sitter. 2010. If you can’t beat them, join them? Explaining social democratic responses to the challenge from the populist radical right in Western Europe. Political Studies 58(3):410–426.

Beinborn, Niclas, Stephan Grohs, Renate Reiter, and Nicolas Ullrich. 2018. „Eigenständige Jugendpolitik“: Varianz in den Ländern. Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft 12(4):743–762.

Berg-Schlosser, Dirk, and Gisèle De Meur. 2009. Comparative research design: case and variable selection. In Configurational comparative methods: qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) and related techniques, ed. Benoît Rihoux, Charles C. Ragin, 19–32. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

Böcher, Michael, and Annette Elisabeth Töller. 2016. Umwelt-und Naturschutzpolitik der Bundesländer. In Die Politik der Bundesländer, ed. Achim Hildebrandt, Frieder Wolf, 259–281. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Bräuninger, Thomas, Marc Debus, Jochen Müller, and Christian Stecker. 2020. Parteienwettbewerb in den deutschen Bundesländern, 2nd edn., Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Budge, Ian. 2015. Issue emphases, saliency theory and issue ownership: a historical and conceptual analysis. West European Politics 38(4):761–777.

Bukow, Sebastian. 2016. The Green Party in Germany. In Green parties in europe, ed. Emilie van Haute, 126–153. London: Routledge.

Carter, Neil. 2013. Greening the mainstream: party politics and the environment. Environmental Politics 22(1):73–94.

Conway, Bethany A., Kate Kenski, and Di Wang. 2015. The rise of Twitter in the political campaign: searching for intermedia agenda-setting effects in the presidential primary. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 20(4):363–380.

De Moor, Joost, Katrin Uba, Mattias Wahlström, Magnus Wennerhag, and Michiel De Vydt. 2020. Protest for a future II: composition, mobilization and motives of the participants in Fridays For Future climate protests on 20–27 September, 2019, in 19 cities around the world. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/ASRUW

Decker, Frank, and Viola Neu. 2018. Handbuch der deutschen Parteien. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Downs, Anthony. 1957. An economic theory of political action in a democracy. Journal of political economy 65(2):135–150.

Dryzek, John S., David Downes, Christian Hunold, David Schlosberg, and Hans-Kristian Hernes. 2003. Green states and social movements: environmentalism in the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, and Norway. Oxford: OUP.

Eder, Nikolaus, Marcelo Jenny, and Wolfgang C. Müller. 2017. Manifesto functions: how party candidates view and use their party’s central policy document. Electoral Studies 45:75–87.

Fridays For Future (FfF). 2020. Forderungen. https://fridaysforfuture.de/forderungen/. Accessed 11 Feb 2021.

Gemenis, Kostas, Alexia Katsanidou, and Sofia Vasilopoulou. 2012. The politics of anti-environmentalism: positional issue framing by the European radical right. In MPSA Annual Conference. Chicago, IL, USA.

Gilljam, Mikael, Mikael Persson, and David Karlsson. 2012. Representatives’ attitudes toward citizen protests in Sweden: the impact of ideology, parliamentary position, and experiences. Legislative Studies Quarterly 37(2):251–268.

Green-Pedersen, Christoffer, and Peter B. Mortensen. 2010. Who sets the agenda and who responds to it in the Danish parliament? A new model of issue competition and agenda-setting. European Journal of Political Research 49(2):257–281.

Guinaudeau, Isabelle, and Simon Persico. 2014. What is issue competition? Conflict, consensus and issue ownership in party competition. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 24(3):312–333.

Harris, Phil, Donna Fury, and Andrew Lock. 2005. The evolution of a campaign: tracking press coverage and party press releases through the 2001 UK General Election. Journal of Public Affairs 5(2):99–111.

Haunss, Sebastian, Dieter Rucht, Moritz Sommer, and Sabrina Zajak. 2019in. Germany. In Protest for a future: Composition, mobilization and motives of the participants in Fridays For Future climate protests on 15 March, 2019 in 13 European cities, ed. Mattias Wahlström, Piotr Kocyba, Michiel De Vydt, and Joost De Moor, 69–81.

Holtmann, Everhard, and Kerstin Völkl. 2016. Die sachsen-anhaltische Landtagswahl vom 13. März 2016: Eingetrübte Grundstimmung, umgeschichtete Machtverhältnisse. Zeitschrift für Parlamentsfragen 47(3):541–560.

Hutter, Swen, and Rens Vliegenthart. 2018. Who responds to protest? Protest politics and party responsiveness in Western Europe. Party Politics 24(4):358–369.

Hutter, Swen, Hanspeter Kriesi, and Jasmine Lorenzini. 2019. Soziale Bewegungen im Zusammenspiel mit politischen Parteien: Eine aktuelle Bestandsaufnahme. Forschungsjournal Soziale Bewegungen 32(2):163–177.

Jahn, Detlef. 2017. New internal politics in western democracies: the impact of the environmental movement in highly industrialized democracies. In Parties, governments and elites, ed. Philipp Harfst, Ina Kubbe, and Thomas Poguntke, 125–150. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Jungherr, Andreas. 2016. Twitter use in election campaigns: a systematic literature review. Journal of information technology & politics 13(1):72–91.

Keman, Hans. 2006. Parties and government: features of governing in representative democracies. In Handbook of party politics, ed. Richard S. Katz, William Crotty, 160–174. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

Kemmerzell, Jörg, and Veith Selk. 2020. Three responses to democracy problems of energy transitions. Political Studieshttps://doi.org/10.1177/0032321720907556.

Knelangen, Wilhelm. 2018. Funktioniert „Jamaika“ nur in Schleswig-Holstein? Warum es zu einer Koalition aus Union, FDP und Bündnis 90/Die Grünen im Norden kam, sie im Bund aber scheitert. In Jahrbuch des Föderalismus 2018, ed. EZFF, 202–213. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

Lockwood, Matthew. 2018. Right-wing populism and the climate change agenda: exploring the linkages. Environmental Politics 27(4):712–732.

Maatsch, Aleksandra. 2014. Are we all austerians now? An analysis of national parliamentary parties’ positioning on anti-crisis measures in the eurozone. Journal of European Public Policy 21(1):96–115.

Meguid, Bonnie M. 2005. Competition between unequals: the role of mainstream party strategy in niche party success. American political science review 99(3):347–359.

Mudde, Cas. 2013. Three decades of populist radical right parties in Western Europe: So what? European Journal of Political Research 52(1):1–19.

Mudde, Cas. 2017. Introduction to the populist radical right. In The populist radical right: a reader, 1–10. London. New York: Routledge.

Müller-Rommel, Ferdinand. 1993. Grüne Parteien in Westeuropa. Entwicklungsphasen und Erfolgsbedingungen. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Neuber, Michael, and Beth Gharrity Gardner. 2020. Germany. In Protest for a future II: composition, mobilization and motives of the participants in Fridays For Future climate protests on 20–27 September, 2019, in 19 cities around the world, ed. J. De Moor, K. Uba, Mattias Wahlström, M. Wennerhag, and M. De Vydt, 117–138.

Peters, B. Guy. 2013. Strategies for comparative research in political science. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Piccio, Daniela R. 2019. Party responses to social movements: challenges and opportunities. Oxford: Berghahn.

Poguntke, Thomas. 2006. Political parties and other organizations. In Handbook of party politics, ed. Richard S. Katz, William Crotty, 396–405.

Raisch, Judith, and Reimut Zohlnhöfer. 2020. Beeinflussen Klima-Schulstreiks die politische Agenda? Eine Analyse der Twitterkommunikation von Bundestagsabgeordneten. Zeitschrift für Parlamentsfragen 51(3):667–682.

Rucht, Dieter. 1996. Wirkungen von Umweltbewegungen: Von den Schwierigkeiten einer Bilanz. Forschungsjournal Neue Soziale Bewegungen 9(4):15–27.

Rucht, Dieter. 2019a. Faszinosum Fridays for Future. Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte 69(47/48):4–9.

Rucht, Dieter. 2019b. Fridays for Future und die Generationenfrage. WZB Mitteilungen. 165:6–8.

Sack, Detlef, and Annette Elisabeth Töller. 2018. Einleitung: Policies in den deutschen Ländern. Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft 12(4):603–619.

Schaller, Stella, and Alexander Carius. 2019. Convenient truths: mapping climate agendas of right-wing populist parties in Europe. Berlin: adeplhi.

Sommer, Moritz, Dieter Rucht, Sebastian Haunss, and Sabrina Zajak. 2019. Fridays for Future: Profil, Entstehung und Perspektiven der Protestbewegung in Deutschland. ipb working paper series, Vol. 2

Spiegel. 2020. Kenia-Bündnis in Sachsen-Anhalt. Die härteste Koalition Deutschlands. https://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/sachsen-anhalt-das-erstaunliche-ueberleben-der-kenia-koalition-a-b175fa35-08ce-41b1-8a80-19ee205e196c. Accessed 11 Feb 2021.

Spoon, Jae-Jae, Sara B. Hobolt, and Catherine E. De Vries. 2014. Going green: explaining issue competition on the environment. European Journal of Political Research 53(2):363–380.

Strøm, Kaare. 1990. A behavioral theory of competitive political parties. American Journal of Political Science 34(2):565–598.

Tarrow, Sidney G. 2011. Power in movement: social movements and contentious politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Thomeczek, Jan Philipp, Michael Jankowski, and André Krouwel. 2019. Die politische Landschaft zur Bundestagswahl 2017. In Die Bundestagswahl 2017, ed. Karl-Rudolf Korte, Jan Schoofs, 267–291. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Töller, Annette Elisabeth. 2017. Verkehrte Welt? Parteien (in) differenz in der Umweltpolitik am Beispiel der Regulierung des Frackings. Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft 27(2):131–160.

Van Haute, Emilie. 2016. Green parties in Europe. London: Routledge.

Van der Brug, Wouter, and Joost Berkhout. 2015. The effect of associative issue ownership on parties’ presence in the news media. West European Politics 38(4):869–887.

Vliegenthart, Rens, Stefaan Walgrave, and Corine Meppelink. 2011. Inter-party agenda-setting in the Belgian parliament: the role of party characteristics and competition. Political Studies 59(2):368–388.

Wagner, Markus. 2012. When do parties emphasise extreme positions? How strategic incentives for policy differentiation influence issue importance. European Journal of Political Research 51(1):64–88.

Wagner, Markus, and Thomas M. Meyer. 2014. Which issues do parties emphasise? Salience strategies and party organisation in multiparty systems. West European Politics 37(5):1019–1045.

Wahlström, Mattias, M. Sommer, P. Kocyba, M. de Vydt, J. De Moor, S. Davies, R. Wouters, M. Wennerhag, J. van Stekelenburg, and K. Uba. 2019in. Protest for a future: Composition, mobilization and motives of the participants in Fridays For Future climate protests on 15 March, 2019 in 13 European cities

Welt. 2019. Die AfD und die „sogenannte Klimaschutzpolitik“. https://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article201093000/CO2-Emissionen-Die-AfD-und-die-sogenannte-Klimaschutzpolitik.html. Accessed 11 Feb 2021.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank Melanie Slavici and Michael Böcher for their feedback on an earlier version of this paper. We are grateful to the three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

L.E. Berker and J. Pollex declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Submission for the ZfVP Special Section “Environmentalism and Populism” with the guest editors: Aron Buzogány, Hans-Joachim Lauth and Christoph Mohamad-Klotzbach

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Berker, L.E., Pollex, J. Friend or foe?—comparing party reactions to Fridays for Future in a party system polarised between AfD and Green Party. Z Vgl Polit Wiss 15, 1–19 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12286-021-00476-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12286-021-00476-7

Keywords

- Environmental politics

- Fridays for Future

- Party competition

- Populist racial right parties

- Social movements