Abstract

The major soy-derived isoflavones such as genistein has been demonstrated to possess anticarcinogenic activity in animal model systems. The present study was designed to investigate the effects of isoflavone genistein exposure at concentrations ranging from 0.01 to 50 μM on the LDL receptor and HMG-CoA reductase gene expression in the estrogen receptor positive DLD-1 human colon cancer cell line. LDL receptor and HMG-CoA reductase gene expressions were evaluated by reverse transcription followed by real-time PCR. Genistein induced an increase of LDL receptor gene expression and later decrease of HMG-CoA reductase mRNA expression in DLD-1 cells. These findings provide direct evidence on the role of genistein in regulating LDL receptor and HMG-CoA reductase gene expression in colon cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Soybeans contain about 40% protein, and depending on the processing procedure, the protein content can reach over 90% as in soy protein isolate (SPI) that is usually used in soy-based infant formulas [39]. Most of the attention in soy studies has been focused on the proteins and their associated isoflavones (ISF). Epidemiological evidences suggest that soy consumption is linked to a lower incidence of chronic diseases including coronary heart disease, atherosclerosis, Type 2 diabetes, osteoporosis, and certain types of cancer such as prostate and breast cancer [31, 39]. In these connections, soy isoflavones have been reported to have a variety of biological activities including estrogenic [32], antioxidative [19], anti-osteoporotic [1] and anticarcinogenic [18] activities. Furthermore, recent clinical trials [2] and animal studies [4, 21, 33] also showed that dietary soy proteins or ISF reduce the risk factors for cardiovascular diseases, lowering triglyceride, total and low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels and increasing the ratio of HDL/LDL cholesterol. However, the reported beneficial health effects were quite variable in different studies and the lack of understanding in the molecular mechanisms by which lipid metabolism is impacted, may contribute a major part to the discrepancies.

Soy proteins and ISF regulate lipid metabolism via multiple cellular pathways (fatty acid biosynthesis, cholesterol synthesis, catabolism and uptake) and through modulation of the key transcription factors including SREBP, PPAR, TR, RAR, and LXR [39]. The same multiple cellular pathways are disregulated in colon cancer [10, 23, 34–36].

Cholesterol is an essential component of cell membrane and the main pathway through which proliferating cells gain cholesterol is de novo synthesis of endogenous cholesterol regulated by the activity of 3-hydroxy-methylglutaryl-coenzymeA (HMG-CoA) reductase. Alternatively, the cellular uptake of circulating LDL after binding to its receptor represents another mechanism of cholesterol acquisition. Several evidences have demonstrated that LDL receptor have a role in cell growth and tumorigenesis [8–10]. We, previously, showed that 63.3% of colon cancer patients did not present LDL receptors and that the absence of LDL receptor predicted shorter survival [8, 9]. Additionally, the absence of LDL receptor in cancers was associated with enhanced endogenous cholesterol synthesis [10]. A loss of LDL receptor in tumors is expected to remove feedback inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase, stimulating endogenous mevalonate pathway [10]. Increased synthesis mevalonate and mevalonate-derived isoprenoids supports increased cell proliferation through the activation of growth-regulatory proteins and oncoproteins and by promoting DNA synthesis [16]. In agreement with these observations the inhibition of mevalonate synthesis and the up-regulation of LDL receptor, therefore may be an effective strategy to impair the growth of colon malignant cells.

Factors that up-regulate LDL receptor gene include estrogen and phytoestrogen in HepG2 cells and in rat liver [7, 13, 15]. Moreover the inhibition of mevalonate synthesis may be exerted by plant isoprenoid and genistein on experimental breast cancer [16]. Genistein has been also shown to decrease cholesterol synthesis in cultured HepG2 [7] and inhibits HMG-CoA reductase activity in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells [17]. It has been suggested that the soy proteins enhance the expression of the LDL receptor in cultured human hepatoma cells [26], animals, and hypercholesterolemic Type 2 diabetic patients [24, 25]. A similar effect has been observed with a soy protein polypeptide in cultured HepG2 cells [27].

Previously, we have demonstrated an estrogenic regulation of cholesterol biosynthesis and cell growth in DLD-1 colon cancer cells. Estrogens induced an early increase of LDL receptor at both mRNA and protein level and later decrease of HMG-CoA reductase activity and protein expression [30].

Then, in the present study, we aimed to investigate whether genistein might affect gene expression of LDL receptor and HMG-CoA reductase in DLD-1 cells, a human colon cancer cell line expressing estrogen receptor β, but lacked estrogen receptor α [3]. If genistein regulation of LDL receptor and HMG-CoA reductase gene expression via estrogen receptor β exists, the use of genistein might be a new approach for colon cancer management.

Methods

Cell culture condition

Human colon adenocarcinoma-derived DLD-1 cells were obtained from the Interlab Cell Line Collection (IST, Genoa, Italy). Cells were routinely cultured in RPMI 1640 without phenol red supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% nonessential amino acids, 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, in monolayer culture, and incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 in air. At confluence, the grown cells were harvested by means of trypsinization and serially subcultured with a 1:4 split ratio. All cell culture components were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Milan, Italy).

Genistein treatment

In the experiments investigating the effect of genistein under estrogen-depleted culture conditions, DLD-1 cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 105 cells/5 ml of phenol red-free RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS in 60 mm tissue culture dishes (Corning Costar Co., Milan, Italy). After 24 h, to allow for attachment, the medium was removed, and RPMI 1640 containing 5% dextran-coated charcoal-treated FBS was added to cell line.

The cells were incubated for further 24 h, and then the medium was replaced by fresh culture medium containing 5% charcoal-stripped FBS with genistein at increasing concentrations (0.01, 1, 10 and 50 μM) dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The cells were allowed to grow for established time and then trypsinized. The cell pellet obtained after low-speed centrifugation was used for subsequent analyses.

Before proceeding with the experiments, estrogen levels were evaluated in the estrogen stripped medium in which DLD-1 cells were seeded by using a specific radioimmunoassay; estrogen levels were found below the detection limit.

Each experiment included an untreated control and a control with the equivalent concentration of DMSO as had been used for adding phytoestrogen. The solvent reached a concentration not higher than 0.3% in all experiments.

Triplicate cultures were set up for each phytoestrogen concentration and for control, and each experiment was repeated four times.

Cell viability, determined using the trypan blue exclusion test, always exceeded 90%.

LDL receptor and HMG-CoA reductase gene expression

DLD-1 cells were cultured with 0.01, 1, 10 and 50 μM of genistein for 30 min, 1, 2, 5 and 24 h in order to evaluate LDL receptor mRNA expression and for 24 and 48 h to analyze mRNA expression of HMG-CoA reductase. Very precocious times of exposure to genistein were tested because LDL-R gene is considered an early gene [5, 30], on the contrary longer times of exposure to genistein are required in order to detect an effect in HMG-CoAR gene expression [13, 30]. In parallel experiments, LDL-R mRNA levels were analysed in DLD-1 cells exposed for 5 h to genistein (0.01 μM) alone and genistein (0.01 μM) plus ICI 182,780 (0.1 μM).

Analysis of gene expression was performed by reverse transcription followed by real-time PCR. Total cell RNA was isolated with TRI-Reagent (Mol. Res. Centre Inc. Cincinnati, O, USA), following the manufacturer’s instruction. Briefly, DLD-1 cells, after exposure to different genistein concentrations, were washed twice in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), scraped in PBS, and vigorously shaken in 0.3 ml of pure distilled water; then, 0.75 ml of TRI-Reagent and 0.2 ml of chloroform were added to cell lysate. The samples were vigorously shaken and centrifuged and the RNA present in the aqueous phase was precipitated with 0.5 ml of isopropanol. The RNA pellet was washed once with 1 ml of 75% ethanol, dried, resuspended in sterile water and quantified by UV absorbance. A sum of 2 μg of total RNA were used for the reverse transcription reaction performed in 20 μl of final volume at 41°C for 60 min, using 30 pmol of antisense primer (Table 1) for analyses of the HMG-CoA reductase, the LDL receptor and the β-actin gene. β-actin gene was utilized as an internal control and it was chosen as a reference gene because it is a housekeeping gene. Real-time PCRs were performed in 25 μl of final volume containing 2 μl of cDNA, master mix with SYBR Green (iQ SYBR Green Supermix Bio-Rad, Milan, Italy) and sense and antisense primers for each target gene. The expression of each gene analysed was detected in separated tubes.

Real-time PCR was carried out in iCycler Thermal Cycler System apparatus (Bio-Rad) using the following parameters: one cycle of 95°C for 1 min and 30 s, followed by 45 cycles at 94°C for 10 s, 55°C for 10 s and 72°C for 30 s and a further melting curve step at 55–95°C with a heating rate of 0.5°C per cycle for 80 cycles. The PCR products were quantified by external calibration curves, one for each tested gene, obtained with serial dilutions of known copy number of molecules (102–107 molecules). All expression data were normalized by dividing the amount of target by the amount of β-actin used as internal control for each sample. The specificity of the PCR product of each tested gene was confirmed by gel electrophoresis.

Assessment of cell proliferation

After DLD-1 cells had been cultured for 24 h with different concentrations of genistein (0.01, 1, 10 and 50 μM), proliferative response was estimated by [3H]-thymidine incorporation and colorimetric MTT-test (Sigma-Aldrich) as previously reported [28, 29].

Statistical analysis

The significance of the differences between the control group and each experimental group was evaluated with one-way analysis of variance and the Dunnett’ post test. Differences were considered significant at a 5% probability level.

Results

The exposure of DLD-1 to different concentrations of genistein, under estrogen-depleted culture conditions, determined an induction of LDL receptor gene expression. In fact, compared to control cells, a good time-dependency of the gene induction was at 1 μM of genistein concentration, while a good dose-dependency was present after 2 h of hormone exposure (Table 2).

Genistein exerted a weak, but not significant, decrease in HMG-CoA reductase gene expression after 24 h of treatment. On the contrary, after 48 h of exposure to increasing concentrations of genistein, DLD-1 cells showed a significant decrease in HMG-CoA reductase mRNA expression starting to 1 μM which was maintained for up 50 μM (Table 3).

To evaluate whether the effect of genistein on LDL receptor mRNA expression in DLD-1 cells was mediated through the estrogen receptor, cells were also exposed to 0.01 μM genistein for 5 h in the presence or absence of 0.1 μM ICI 182,780 (a pure estrogen receptor antagonist). ICI 182,780 completely abolished the stimulation of LDL receptor gene induced after 5 h of exposure (Fig. 1).

LDL-R mRNA levels in DLD-1 cells exposed for 5 h to genistein (0.01 μM) alone and genistein (0.01 μM) plus ICI 182,780 (0.1 μM). Data displayed as mean ± SE of number molecules mRNA LDL receptor/number molecules mRNA β-actin. P value was determined by one-way analysis with Dunnett’ post-test. *P < 0.05 versus control (CTR)

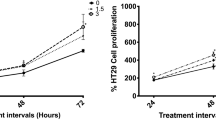

Exposure of the DLD-1 cell line to increasing concentrations of genistein (from 0.01 to 50 μM) under estrogen-depleted culture conditions showed an evident antiproliferative action, measured by 3H-thymidine incorporation and the colorimetric MTT method.

Figure 2 shows the effect of increasing concentrations of genistein on the incorporation of 3H-thymidine in DNA of DLD-1 cells after 24 h. Concentrations equal to or higher than 10 μM of the isoflavone caused a significant reduction of cell proliferation.

As with 3H-thymidine incorporation, the formazan-generated MTT decreased in dose-dependent manner, from 0.01 to 50 μM of genistein concentrations after 24 h of exposure (data not shown).

Discussion

Factors that up-regulate LDL receptor expression in normal and neoplastic cells include multiple growth factors, many hormones (such as insulin, glucagons, growth hormone) and steroid hormones, such as estrogens. Some authors have demonstrated, both in vivo and in vitro, a stimulation of LDL receptor mRNA and protein expression in hepatoma cell line HepG2 and in rat liver by a natural estrogen, 17β-estradiol, suggesting an estrogen regulation of hepatic LDL receptor expression [13, 15]. Recently, it has been showed that diets containing soy protein enhance the clearance of apoB-containing lipoproteins via LDL receptors expressed on the hepatocyte plasma membrane [7].

Dietary factors may regulate HMG-CoA reductase activity with implications for breast cancer development [16]. Kojima et al. have demonstrated that genistein itself and/or its metabolites may suppress hepatic lipid synthesis [20].

In this report, we show that LDL receptor and HMG-CoA reductase gene expression are affected by genistein in DLD-1 cell line. The phytoestrogen genistein is present in relatively high amounts in soybeans and it is able to induce LDL receptor gene expression and down-regulate HMG-CoA reductase gene in DLD-1 cells via estrogen receptor β. The effect of genistein treatment on LDL receptor gene expression was dose-dependent after 2 h. A good time-dependency was present at 1 μM of genistein.

In addition, genistein, exerted an evident antiproliferative action on DLD-1 cells in a dose-dependent manner.

These findings provide direct evidence of the relationship between phytoestrogens and cholesterol pathway, representing a promising basis for the comprehension of the mechanism of estrogen and phytoestrogens action in gastrointestinal tract. We have already showed that estrogens modulate the colon cancer proliferation by the up regulation of LDL receptor and the down regulation of HMG-CoA reductase activity [30], suggesting that the cholesterol metabolism could be considered an additional target for the estrogenic antiproliferative properties in colon cancer.

The estrogen-gene regulated transcription utilizes different pathways depending on the cellular contex. It is known that at hepatic level the induction of LDL receptor gene by estrogen is mediated by non transcriptional factors, but if a similar mechanism exists in colon cells is not currently known. Moreover, genistein is also a tirosyne kinase inhibitor and therefore can affect the cell signal transduction pathway through this way. Further studies are required to identify this molecular mechanism.

HMG-CoA reductase is the key enzyme of mevalonate biosynthesis [37]. A reduction of the HMG-CoA reductase expression by genistein may decrease the mevalonate pool, thus limiting protein isoprenylation, which involves the post-translational covalent attachment of a lipophilic farnesyl or geranylgeranyl isoprenoid group to several proteins [11]. Many prenylated proteins, like Ras, lamin B, and Rho regulate cell growth and/or transformation. The up-regulation of LDL receptor by genistein make to an increased cholesterol intracellular content, modulating HMG-CoA reductase gene expression and consequently controlling cell proliferation and transformation.

Our findings support a variety of studies that have linked the soy-derived isoflavones, such as genistein, with anti-tumorigenic activity [6, 12]. Genistein has been demonstrated to reduce proliferation and induce G2/M phase arrest and apoptotic death in colon cancer HT-29 cells [40]. Genistein increased expression of Bax and p21WAF1 and slightly decreased Bcl-2 level and resulted to inhibit the viability of human colon cancer HT-29 cells via induction of apoptosis. In a previous study, we showed that genistein can affect growth of DLD-1 cells by both decreasing polyamine biosynthesis and inducing apoptosis [22]. It is known that high polyamine levels are associated with fast proliferating cells [38] and that polyamine levels in colon cancer are significantly increased compared to normal and preneoplastic tissue [14]. Therefore, the reduction of polyamine levels represents an antiproliferative mechanism, offered by genistein, against colon cancer growth. Genistein produces suggestive effects for estrogenicity given that it can induce estrogen-responsive gene products, as LDL receptor. This estrogen agonistic activity of genistein may account for the beneficial effects of this compound against colon cancer development. A central role of genistein in prevention of colon tumor and in reduction of colon tumor growth might be considered.

References

Anderson JJB, Garner SC (1997) The effects of phytoestrogens on bone. Nutr Rev 17:1617–1632

Anderson JW, Jhonstone BM, Cook N (1995) Meta-analysis of the effects of soy protein intake on serum lipids. N Engl J Med 333:276–282

Arai N, Strom A, Rafter JJ, Gustafsson (2000) Estrogen receptor β mRNA in colon cancer cells: growth effects of estrogen and genistein. Biochem Biophys Res Comm 270:425–431

Ascenscio C, Torres N, Isoard-Acosta F, Gomez-Perez FJ, Hernandez-Pando R, Tovar AR (2004) Soy protein affects serum insulin and hepatic SREBP-1 mRNA and reduces fatty liver in rats. J Nutr 134:522–529

Bocchetta M, Bruscalupi G, Castellano F, Trentalance A, Komaromy M, Fong LG, Cooper AD (1993) Early induction of LDL receptor gene during rat liver regeneration. J Cell Physiol 156:601–609

Booth C, Hargreaves Df, Hadfield JA, McGown AT, Potten CS (1999) Isoflavones inhibit intestinal epithelial cell proliferation and induce apoptosis in vitro. Br J Cancer 80:1550–1557

Borradaile NM, de Dreu LE, Wilcox LJ, Edwards JY, Huff MW (2002) Soya phytoestrogens, genistein and daidzein, decrease apolipoprotein B secretion from HepG2 cells through multiple mechanisms. Biochem J 366:531–539

Caruso MG, Notarnicola M, Cavallini A, Guerra V, Misciagna G, Di Leo A (1993) Demonstration of low density lipoprotein receptor in human colonic carcinoma and in surrounding mucosa by immunoenzymatic assay. Ital J Gastroenterol 25:361–367

Caruso MG, Osella AR, Notarnicola M, Berloco P, Leo S, Bonfiglio C, Di Leo A (1998) Prognostic value of low density lipoprotein receptor expression in colorectal carcinoma. Oncol Rep 5:927–930

Caruso MG, Notarnicola M, Santillo M, Cavallini A, Di Leo A (1999) Enhanced 3-HMGCoA reductase activity in human colorectal cancer not expressing low density lipoprotein receptor. Anticancer Res 19:451–454

Clarke S (1992) Protein isoprenylation and methylation at carboxyl-terminal cystein residue. Annu Rev Biochem 61:355–86

Crowell PL (1999) Prevention and therapy of cancer by dietary monoterpenes. J Nutr 129:775S–778

Di Croce L, Bruscalupi G, Trentalance (1996) Independent behaviour of rat liver LDL receptor and HMGCoA reductase under estrogen treatment. Biochem Biophys Res Comm 224:345–350

Di Leo A, Messa C, Russo F, Misciagna G, Guerra V, Taveri R, Leo S (1994) Prognostic value of cytosolic estrogen receptors in human colorectal carcinoma and surrounding mucosa. Preliminary results. Dig Dis Sci 9:2038–2042

Di Stefano E, Marino M, Gillette JA, Hanstein B, Pallottini V, Bruning J, Krone W, Trentalance A (2002) Role of tyrosine kinase signaling in estrogen-induced LDL receptor gene expression in HepG2 cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 1580:145–149

Duncan RE, El-Sohemy A, Archer MC (2005) Dietary factors and the regulation of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase: implication for breast cancer and development. Mol Nutr Food Res 49:93–100

Dyck JRB, Kudo N, Barr AJ, Davies SP, Hardie DG, Lopaschuk GD (1999) Phosphorylation control of cardiac acetyl-CoA carboxylase by cAMP-dependent protein kinase and 5′-AMP activated protein kinase. Eur J Biochem 262:184–190

Herman C, Adlercreutz T, Goldin BR, Gorbach SL, Hockerstedt KAV, Watanabe S, Hamalainen EK, Markkanen MH, Makela TH, Wahala KT, Hase TA, Fotsis T (1995) Soybean phytoestrogen intake and cancer risk. J Nutr 125:757S–770S

Kapiotis S, Herman M, Held I, Seelos C, Ehringer H, Gmeiner BM (1997) Genistein, the dietary-derived angiogenesis inhibitor, prevents LDL oxidation and protects endothelial cells from damage by atherogenic LDL. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 17:2868–2874

Kojima T, Uesuqi T, Toda T, Miura Y, Yagasaki K (2002) Hypolipidemic action of the soybean isoflavones genistein and genistein in glomerulonephritic rats. Lipids 37:261–265

Lin Y, Meijer GW, Vermer MA, Trautwein EA (2004) Soy protein enhances the cholesterol-lowering effect of plant sterol esters in cholesterol-fed hamster. J Nutr 134:143–148

Linsalata M, Russo F, Notarnicola M, Guerra V, Cavallini A, Clemente C, Messa C (2005) Effects of genistein on the polyamine metabolism and cell growth in DLD-1 human colon cancer cells. Nutr Cancer 52:83–92

Linsalata M, Giannini R, Notarnicola M, Cavallini A (2006) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase gene expressions are significantly correlated in human colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer 6:191–198

Lovati MR, Manzoni C, Canadesi A, Sirtori M, Vaccarino V, Marchi M, Gaddi G, Sirtori CR (1987) Soybean protein diet increases low density lipoprotein receptor activity in mononuclear cells from hypercholesterolemic patients. J Clin Invest 80:1498–1502

Lovati MR, Manzoni C, Agostinelli P, Ciappellano S, Mannucci L, Sirtori CR (1991) Studies on the mechanism of the cholesterol lowering activity of soy proteins. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 1:18–24

Lovati MR, Manzoni C, Gianazza E, Sirtori CR (1998) Soybean protein products as regulators of liver low-density lipoprotein receptors. I. Identification of active b-conglycinin subunits. J Agric Food Chem 46:2474–2480

Manzoni C, Lovati MR, Gianazza E, Sirtori CR (1998) Soybean protein products as regulators of liver low-density lipoprotein receptors. II a-a’ rich commercial soy concentrate an a′ deficient mutant differently affect low-density lipoproetin receptor activation. J Agric Food Chem 46:2481–2484

Messa C, Pricci M, Linsalata M, Russo F, Di Leo A (1999) Inhibitory effect of 17β-estradiol on growth and the polyamine metabolism of a human gastric carcinoma cell line (HGC-27). Scand J Gastroenterol 34:79–84

Messa C, Russo F, Pricci M, Di Leo A (2000) Epidermal growth factor and 17β-estradiol effects on proliferation of a human gastric cancer cell lines (AGS). Scand J Gastroenterol 35:753–58

Messa C, Notarnicola M, Russo F, Cavallini A, Pallottini V, Trentalance A, Bifulco M, Laezza C, Caruso MG (2005) Estrogenic regulation of cholesterol biosynthesis and cell growth in DLD-1 human colon cancer cells. Scand J Gastroenterol 40:1454–1461

Messina M, Persky V, Setchell KDR, Barnes S (1994) Soy intake and cancer risk: a review of the in vitro and in vivo data. Nutr Cancer 21:113–131

Messina M (2000) Soyfoods and soybean phyto-oestrogens (isoflavones) as a possible alternative to hormone replacement therapy (HRT). Eur J Cancer 36:71S–72S

Moriyama T, Kishimoto K, Nagai K, Urade R, Ogawa T, Utsumi S, Maruyama N, Maebuchi M (2004) Soybean beta-conglycin diet suppress serum triglyceride levels in normal and genetically obese mice by induction of beta-oxidation, down-regulation of fatty acid synthase and inhibition of triglyceride absorption. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 68:352–359

Notarnicola M, Messa C, Cavallini A, Bifulco M, Tecce MF, Eletto D, Di Leo A, Montemurro S, Laezza C, Caruso MG (2004) Higher farnesyl diphosphate synthase activity in human colorectal cancer: inhibition of cellular apoptosis. Oncology 67:351–358

Notarnicola M, Altomare DF, Calvani M, Orlando A, Bifulco M, D’Attoma B, Caruso MG (2007) Fatty acid synthase hyperactivation in human colorectal cancer: relationship with tumor side and sex. Oncology 71:327–332

Rao KN (1995) The significance of cholesterol biosynthetic pathway in cell growth and carcinogenesis. Anticancer Res 15:309–314

Siperstein MD (1984) Role of cholesterogenesis and isoprenoid synthesis in DNA replication and cell growth. J Lipid Res 25:1462–1468

Tabor CW, Tabor H (1984) Polyamines. Annu Rev Biochem 53:749–790

Xiao CW, Mei J, Wood CM (2008) Effect of soy proteins and isoflavones on lipid metabolism and involved gene expression. Front Biosci 13:2660–2673

Yu Z, Li W, Liu F (2004) Inhibition of proliferation and induction of apoptosis by genistein in colon cancer HT-29 cells. Cancer Lett 215:159–166

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Notarnicola, M., Messa, C., Orlando, A. et al. Effect of genistein on cholesterol metabolism-related genes in a colon cancer cell line. Genes Nutr 3, 35–40 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12263-008-0082-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12263-008-0082-5