Abstract

Objectives

This study investigated the incidence of caries in infants and explored the risk factors related to noteworthy variations between urban and rural areas.

Methods

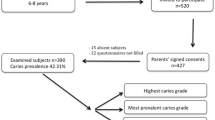

Subjects were 232 infants (111 males and 121 females) aged 1.6 and 3 years born in “N” town between the fiscal years of 1997 and 2001. Infants aged 1.6 and 3 years had 99.6 and 100% participation in health checkups, respectively. Of the total, 148 and 84 infants were living in the urban and rural areas, respectively, of “N” town.

Results

Caries incidence and the average number of carious teeth (decayed/missing/filled teeth, dmft) for infants aged 1.6 years were significantly higher in the rural area than in the urban area, indicating that environmental factors that predispose infants to develop dental caries exist in the rural area. In addition, logistic regression analysis for infants in each of the two areas revealed that risk factors of the child-care environment, for example living with grandparents and brushing by parents, stood in marked contrast with each other. Moreover, the odds ratio of the risk factor dozing off while drinking showed a marked difference between the areas, although this risk factor was common in both areas.

Conclusions

The results of this study indicated that several factors of the child-care environment, for example the daytime caring person, are related with caries development. Scientific elucidation of the risk factors that give rise to high prevalence of caries in specific regions and access to the whole picture of the disease mechanism may have great potential to lead to the development of effective countermeasures and to contribute to the reduction of dental caries in preschool children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

After reconstruction, the Japan of the post-World War 2 period had rapid economic development and, together with this, greatly increased incidence of childhood caries (more than 80%); the so-called “flood of decayed teeth in children”. In recent years, caries prevalence in infants has decreased significantly in Japan, being regarded as a slight illness. However, prevalence of early childhood caries in Japan is still higher than in other developed countries [1].

Studies on caries prevalence in infants have taken into consideration several important aspects such as race [2–4], the gap between the rich and the poor [5], lifestyle [6–10], social class [11, 12] and so forth. By recognizing the influence of modernization and changes in the social environment, those multi-faceted [13] studies have made a valuable contribution to the prevention of tooth decay.

Studies that compared caries incidence in urban and rural areas with regard to their environmental and lifestyle differences only have been performed since 1980 [1, 14–17]. However, to our knowledge, studies analyzing the characteristics of different areas inside a certain municipality are rare [15, 16, 18]. Recently we have found “N” town in which the rural area has higher caries incidence than the urban area [19]. However, there have been few studies which uncover the risk factors yielding the differences in caries prevalence in such areas.

“N” town can be roughly divided into a functional urban area, provided with good infrastructure, and a mountainous rural area, where the majority of the houses are widely dispersed. Taking into account the characteristics of the subjects in both areas, this study intended to make clear the risk factors that influence significant differences in caries prevalence in the different areas of “N” town. By investigating the risk factors of early childhood caries, this study also aimed to contribute to the development of effective directions for prevention of caries.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Subjects were 232 infants (111 males and 121 females) born in “N” town between the fiscal years of 1997 and 2001. Data were collected when infants were 1.6 and 3 years old and correspond to the same individuals at both ages. Infants aged 1.6 and 3 years had 99.6% and 100% participation in health checkups, respectively. Of the total, 148 and 84 infants were living in the urban and rural areas, respectively, of “N” town.

Characteristics of “N” town and its areas

“N” town (Fig. 1) is located in a region blessed with abundant nature and has about 87% of its total area (160.27 km2) covered by mountains. At the time this study was carried out, in November 2005, the number of households in “N” town was 2,789, the population was 9,447 people, each household was composed of an average of 3.39 people, the ratio of elderly was 24.7%, and the population density was 58 people per square kilometer. The number of births per year in “N” town is about 50.

Thanks to cooperation among the associations of physicians, dentists, and dental hygienists and health-care centers, newborns aged 4 months, 1.6 and 3 years have been given health checkups. In addition, despite several inconveniences found in the rural area of “N” town, implementation of a mobile health checkup unit has provided health examination for nearly 100% of the infants living in that area. Furthermore, dental health checkups in infants aged 1.6 and 3 years have been carried out with enthusiasm and, unlike other towns in Aichi prefecture, gratis examinations for infants aged 1 and 2 years also have been implemented. Moreover, charged fluoride applications in infants aged 3 years or less have been carried out when the parents requested them.

The characteristics of the areas selected for this study were as follows:

-

1)

Urban Area where the offices, banks, libraries, and shopping malls are concentrated. Provided with good infrastructure and containing 58.8% of the population and 58.6% of the total households of the town. Frequent moving in and out, and predominance of nuclear families. This area has one dental clinic.

-

2)

Rural Mountainous region 2.84-fold larger than the urban area where houses are widely dispersed, and containing 41.2% of the population and 41.4% of the total households of the town. Most of the inhabitants are native. Families are basically composed of three generations and patriarchy remains. The presence of strong community awareness is evident. This area also has one dental clinic.

Methods

Data were obtained from the health-control documentation (slips) of mother and child and from questionnaires filled out by mothers. The contents of health guidance and information such as those acquired by physical measurements (stature, body weight, Kaup index), interviews carried out by public health professionals, dental examination (number of carious teeth, number of filled teeth, number of silver-coated teeth, pattern of caries prevalence, situation of stained teeth, presence/absence of abnormal soft tissue, other dental abnormalities, finger chewing), and medical examination performed by the pediatrician were collected from health-control records pertaining to infants aged 1.6 and 3 years. Data on the child-care environment (residence area, household composition, birth order, daytime caring person, etc.), lifestyle (snack composition, habit of brushing teeth, dietary habits, etc.), physical and mental development (language development, understanding, general habits, recreation, etc.), and number of fluoride applications were obtained from questionnaires filled out by mothers. The number of dental checkups performed between 1 and 2 years of age was extracted from the health-control documentation of mother and child.

Inspection of the oral health status of infants aged 1.6 and 3 years in “N” town was performed by six dentists (two working permanently in “N” town and four from a nearby city), who followed the standards set by the Mother and Child Health Checkup Manual of the Aichi prefecture. Questionnaires were mailed to the guardians together with notifications of health checkup for infants when they were 1.6 and 3 years old.

Caries prevalence conditions were classified according to the ratio of infants with decayed teeth, the average number of carious teeth per infant (dmft), and the pattern of caries incidence (0, no carious tooth; A, maxillary frontal or molar teeth with caries; B, molar and maxillary frontal teeth with caries; C, carious teeth including the inferior frontal ones).

Data analyses were performed as follows:

-

1)

Descriptive statistical analysis of total caries prevalence.

-

2)

Comparative analysis of caries prevalence in urban and rural areas. The Pearson’s Chi-squared test and the t test were used.

-

3)

Descriptive analysis of the relationship between the presence/absence of caries in infants aged 1.6 years and the pattern of caries prevalence in infants aged 3 years.

-

4)

Specifically, 12 items were selected from the 103 items that composed the data extracted from the health-control documentation of mother and child. First, based on the results of the descriptive statistical analysis, 21 items that have a direct relationship with oral health and caries and four items that have indirect relationship with caries development and psychosomatic development of the infants (e.g., the state of the feces, type of recreation with friends at 3 years of age) were extracted. Next, qualitative variables and those that had too many missing values were excluded, so that the 21 variables directly related with oral health were narrowed down to 11 variables present at 1.6 years of age. Finally, given the difficulty of providing evidence on the cause-and-effect relationship and the nonexistence of previous studies on this matter, the four variables related to the psychosomatic development of the infants were excluded. Carious tooth at 3 years of age was set as the response variable, and then logistic regression analyses were performed per residence area for the ten items that were set as risk factors. As infants who had missing values for any of the 12 items (including the response variable) were excluded from data analysis, the final number of subjects became 188 (120 subjects in the urban area and 68 subjects in the rural area). Type III analysis of the SAS logistic procedure was used for analysis of the effect of the risk factors.

Ethical considerations

Following detailed explanation of the objectives and methods of the study, approval from the institutional administrator was obtained by means of exchange of written consent. All identifiable personal information was adequately disguised in the data provided by “N” town in order to preserve the anonymity of the individuals involved. This procedure was based on the ethical guidelines set by the Japan Epidemiological Association, which standardizes the policy to be followed by researchers when informed consent cannot be obtained from the subjects.

This study was approved by the Committee on Human Research of the Aichi Gakuin University (Department of Health Science, Faculty of Psychological and Physical Science) on March 22, 2006 (receipt number 0506).

Results

Dental health and caries prevalence in “N” town

Nine of the 232 infants aged 1.6 years had carious teeth and, as seven of them (77.8%) lived in the rural area, total caries prevalence was significantly higher and dmft tended to be elevated in the rural area (Table 1). For infants aged 3 years, both caries prevalence and dmft were markedly higher in the rural area than in the urban area (Table 1). Of the nine 1.6-year old infants who had carious teeth, six (66.7%) showed a type B pattern of carious incidence at age 3 years. On the other hand, 55 (24.7%) of the 223 infants who had healthy teeth at 1.6 years of age but had caries at 3 years of age exhibited a type A pattern of carious incidence.

Charged fluoride applications in infants were implemented in “N” town as a result of joint cooperation among the associations of dentists and dental hygienists and health-care centers. Regional differences in the ratios of dental health checkups and fluoride applications in infants aged 1–2 years were not observed (Table 2).

Comparison of the risk factors for caries in urban and rural areas

In order to clarify the risk factors which might have given rise to significant differences in caries prevalence in the two areas, we performed logistic regression analysis separately for the data in these areas.

The likelihood ratio Chi-squared test of the overall goodness of fit of the model resulted in a significance level of 5% for infants in the urban area (χ 2 = 23.7169, df = 13, P = 0.0338). Type III analysis indicated that the factor daytime caring person was significantly related with caries incidence (Wald χ 2 = 6.1768, P = 0.0129). In addition, it showed that the factors living with grandparents, dozing off while drinking, and snack eating frequency tended to be associated with caries incidence. Wald χ 2 statistics with dfs and corresponding P-values for the three factors were, in the order they are described above, 4.3063 (df = 2, P = 0.1161), 2.2490 (df = 1, P = 0.1337), and 2.8741 (df = 1, P = 0.0900).

We then estimated the odds ratios corresponding to 2 × 2 contingency tables and their 95% confidence intervals for caries prevalence in the urban area (Table 3). Here, we shall describe exclusively the odds ratios that had statistical significance or tendency to significance. First, the odds of the presence of caries in infants living with a grandmother or grandfather were nearly fourfold higher than those for infants living with neither a grandmother nor grandfather. Second, the odds of the presence of caries in second-born infants were about 34% those for third or later-born infants. Third, the odds of the presence of caries in infants who dozed off while drinking were nearly 2.6 times higher than the odds for infants who did not doze off while drinking. Fourth, the odds of caries incidence in infants who ate one or two snacks were nearly 35% of the odds for infants, who had three or more snacks between meals. Finally, the odds when the daytime caring person was the mother or the nursery school staff were less than 20% of those when the daytime caring person was a grandmother (Table 3).

In contrast with the urban area, the likelihood ratio Chi-squared test of the overall goodness of fit of the model resulted in a tendency to significance for infants in the rural area (χ 2 = 18.7682, df = 13, P = 0.1305). Type III analysis indicated that the factor doze off when drinking was significantly related with caries incidence (Wald χ 2 = 7.1009, df = 1, P = 0.0077). Furthermore, Type III analysis revealed that the factors living with grandparents, brushing by parents, snack-eating frequency, and daytime caring person tended to associate with caries incidence in infants living in the rural area. Wald χ 2 statistics with dfs and corresponding P-values for the four factors were, in the order they are described above, 4.5463 (df = 2, P = 0.1004), 2.1292 (df = 1, P = 0.1445), 3.0712 (df = 1, P = 0.0797), and 3.5287 (df = 1, P = 0.0603).

We estimated the odds ratios corresponding to 2 × 2 contingency tables and their 95% confidence intervals for caries prevalence in the rural area (Table 4).

The odds ratios that had statistical significance or tendency to significance are described below. First, the odds of the presence of caries in infants living with both a grandmother and grandfather were nearly 22% of those for infants living with neither a grandmother nor a grandfather. This result is clearly different from that in the urban area. Moreover, the odds for infants living with a grandmother or grandfather were nearly fourfold higher than those for infants in the third category in the urban area, whereas those odds were less than unity in the rural area.

Second, the odds of the presence of caries in infants who had their teeth brushed every day were about 34% of those for infants whose parents occasionally or never brushed their teeth. This result also is clearly different from that exhibited in the urban area, because the corresponding odds ratio in the urban area was more than unity.

Third, the odds of the presence of caries in infants who dozed off while drinking were nearly 13 times higher than the odds for infants who did not doze off while drinking. This result is in marked contrast with that obtained in the urban area, which had an odds ratio of less than 3. Nevertheless, this risk factor was common in both areas.

Fourth, the odds of caries incidence in infants who ate one or two snacks were nearly 30% of the odds for infants who had three or more snacks between meals.

Finally, the odds when the daytime caring person was the mother or nursery school staff were just above 20% of those when the daytime caring person was a grandmother (Table 4). Although there were clear differences for the first three results between the urban area and rural area, odds ratios for the fourth and fifth results and the birth order are almost the same in both areas.

Discussion

When urban and rural areas were compared in relation to caries prevalence and dmft in infants aged 1.6 and 3 years, both caries prevalence and dmft were significantly higher in the rural area than in the urban area. In 1984, Sakuma [15] reported that caries prevalence in infants aged 3 years was significantly higher in the peripheral than in the central area of a city. In addition, in 1990, Sakuma [16] reported that infants living in an urban area had lower dmft than infants who lived in two different rural areas. In this study we have obtained similar results: clear differences between the two areas of “N” town were detected.

Studies that compared urban and rural areas have obtained divergent results concerning the relationship between child-care environment and caries development. Although two studies [20, 21] have concluded that “living with grandparents” is not a risk factor for caries development, other studies have found that child care by grandparents is related to caries development in infants aged 3 years [9, 22, 23]. In this study, logistic regression analysis carried out to compare differences in the factor residence area identified that caries incidence in infants aged 3 years in the urban area tended to be high (odds ratio 3.868) when they lived with their grandmothers or their grandfathers. However, in the rural area, caries incidence was significantly low (odds ratio 0.217) in infants who lived with both a grandmother and grandfather. That is to say, added to the exclusion of “living with grandparents” as a risk factor for caries development, infants who lived with both a grandmother and grandfather in the rural area had significantly decreased caries incidence. Therefore we suppose that, in a rural area with deficient infrastructure and low population density, child care support by the grandparents underlies this phenomenon. In addition, the fact that the presence of both husband and wife facilitates the stability of familiar relationships may explain the observed differences between “living with both a grandmother and grandfather” and “living with a grandmother or grandfather”. Moreover, influence of grandparents on caries development may differ in areas with clearly different lifestyles and, thus, it is important to analyze these areas separately.

Reports also disagree with regard to whether “grandparents as daytime caring persons” is [9, 15] or is not [20] a risk factor for caries incidence in infants. In this study, caries incidence in both areas was higher or tended to be higher when the daytime caring person was a grandmother than when the daytime caring person was the mother or the nursery school staff.

Until now, several studies have been performed on the relationship between use of milk bottle or the habit of having snacks and early childhood caries. The conclusion that infants aged 1.6 years have high incidence of caries when they are given milk during the hours of sleep [16, 23] is in agreement with the finding that newborns who are continually breast-fed or given milk through the milk bottle until 1.6 years of age tend to have carious teeth [9, 15, 24]. Moreover, both the custom of having snacks and high plaque score have been regarded as important factors that influence caries development [10, 12]. In this study, although similar results were obtained, infants living in the rural and urban areas who had the custom of dozing off while drinking were shown to have 13.3 and 2.6-fold more caries, respectively, than infants who did not doze off while drinking. Among the risk factors, the only factor that showed a difference between urban and rural areas was brushing by parents. In other words, while the odds ratio of every day teeth brushing to occasional or absence of teeth brushing was 1.229 in the urban area, it was only 0.340 in the rural area—a clearly reverse situation. Therefore, given that the odds of the presence of caries in infants who had their teeth brushed every day were just above 30% of those for infants whose parents occasionally or never brushed their teeth, we consider that thorough guidance on the need for brushing of teeth by parents from the time when milk teeth start to appear will contribute to a reduction of caries incidence in rural areas.

Notwithstanding the declaration of Sakamoto et al. [25] that “despite the existence of great regional differences in Japan’s dental health guidelines, standardized procedures to confront the national average of caries incidence have been planned and put into effect”, dental health guidance has tended to be implemented in the same way as in the past and this situation is not limited to “N” town. So far, investigations about regional differences in caries prevalence and implementation of health-related educational activities adapted to local requirements have hardly been put into practice. It becomes essential, thus, to fill the gap between scientific knowledge and action of the people in order to improve dental health guidance. Finally, scientific elucidation of the risk factors that give rise to high prevalence of caries in specific regions and access to the whole picture of the disease mechanism have great potential to lead to the development of effective countermeasures and to contribute to the reduction of dental caries in infants.

References

Kawaguchi Y, Shinada K, Furukawa K. An epidemiological view of the dental health situation in Japan. J Tokyo Dent Assoc. 2003;51:527–35 (article in Japanese).

Verrips GH, Kalsbeek H, Eijkman MAJ. Ethnicity and maternal education as risk indicators for dental caries, and the role of dental behavior. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1993;21:209–14.

Watt R, Sheiham A. Inequalities in oral health: a review of the evidence and recommendations for action. Br Dent J. 1999;187:6–12.

Willems S, Vanobbergen J, Martens L, Maeseneer JD. The independent impact of household- and neighborhood-based social determinants on early childhood caries: a cross-sectional study of inner-city children. Fam Community Health. 2005;28:168–75.

Kaste LM, Drury TF, Horowitz AM, Beltran E. An evaluation of NHANES III estimates of early childhood caries. J Public Health Dent. 1999;59:198–200.

Grindefjord M, Dahllöf G, Ekström G, Höjer B, Modéer T. Caries prevalence in 2.5-year-old children. Caries Res. 1993;27:505–10.

Marthaler TM. Epidemiological and clinical dental findings in relation to intake of carbohydrates. Caries Res. 1967;1:222–38.

Kawabata K, Miyagi M, Sasahara H, Kawamura M, Kitamoto J, Nagao M, et al. Maternal and child dental health care at a public health center. J Dent Health. 1992;42:101–8 (article in Japanese).

Mitoh S. Lifestyle factors affecting prevalence of dental caries in infants in Onomichi-city. J Dent Health. 2006;56:688–708. (article in Japanese).

Okuno M, Kani T, Shimizu H. A cohort study on dental caries in infants. Jap J Pub Health. 1994;41:625–8. (article in Japanese).

Milen A, Hausen H, Heinonen O, Paunio I. Caries in primary dentition related to age, sex, social status, and county of residence in Finland. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1981;9:83–6.

Wennhall I, Matsson L, Schröder U, Twetman S. Caries prevalence in 3-year-old children living in a low socio-economic multicultural urban area in southern Sweden. Swed Dent J. 2002;26:167–72.

Drury TF, Horowitz AM, Ismail AI, Maertens MP, Rozier RG, Selwitz RH. Diagnosing and reporting early childhood caries for research purposes. J Public Health Dent. 1999;59:192–7.

Inoue S, Ito H. Caries and its prevention. In: Yonemitsu M, Kobayashi S, Miyazaki H, Kawaguchi Y, editors. Contemporary preventive dentistry. Tokyo: Ishiyaku Publishers; 1993. pp. 61–73 (book in Japanese).

Sakuma T. Prevalence of dental caries of three-year-old children in Koriyama. Tohoku Univ Dent J. 1984;3:9–15 (article in Japanese).

Sakuma S. Epidemiological study of dental caries prevalence in deciduous teeth. J Dent Health. 1990;40:678–94. (article in Japanese).

Nakamura K, Kurita K, Kanehira T, Takehara J, Hongo H, Okubo R, et al. Caries prevalence in infants in 5 areas of Hokkaido in 2001. Hokkaido J Dent Sci. 2002;23:34–9 (article in Japanese).

Nakahara Y, Kurazumi R, Sogame A, Tsutsui H. A questionnaire-based study on the relationship between life conditions and caries in infants aged 3 years. J Public Health Pract. 1998;62:674–7 (article in Japanese).

Ohsuka K, Ohsawa I, Sato S, Kataoka I, Nakagaki H, Oshida Y. Comparison between the incidence of caries in urban and rural areas of the “N” town and examination of its lifestyle- and environmental-related determinants. 52nd Meeting of the Tokai Public Health Association, Obu city, 2006 (abstract in Japanese).

Nagai Y, Yata S, Tenpaku N, Higashigawa A, Sakamoto K, Minami T, et al. On the health conduct of 1.5- and 3-year old children and the occurrence of caries in 3-year old children. 58th Meeting of the Japanese Society of Public Health, Oita city, 1999 (abstract in Japanese).

Mizoguchi K, Kurumado K, Tango T, Minowa M. Study on factors for caries and infant feeding characteristics in children aged 1.5–3 years in a Kanto urban area. Jap J Pub Health. 2003;50:867–78 (article in Japanese).

Watanabe A, Horiuchi K, Tsurumoto A, Fukushima M, Kitamura C. Regional diagnosis of the high-risk factors that cause deciduous tooth caries. J Dent Health. 1999;49:558–9 (article in Japanese).

Eda S, Miyazawa H. The environment of life and the development of caries in children. J Child Health. 1996;55:347 (abstract in Japanese).

Wakabayashi Y, Kitahara M, Hashimoto K, Fukuda J, Watanabe A, Iizawa T, et al. Predictive assessment of the caries occurrence tendency in newborns. Jap J Pub Health. 1997;44:1157 (abstract in Japanese).

Sakamoto M, Taura K, Kusumoto M. Caries prevalence in 3-year-old children in all Japanese prefectures and culture and socio-economic status: analyses for possible factors causing prefectural differences. J Dent Health. 2001;51:20–8 (article in Japanese).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Gustavo Bajotto for translating the manuscript into English. We also thank Professor Gregory L. Rohe for proofreading of the English manuscript. We are indebted to anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions and comments on earlier versions of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ohsuka, K., Chino, N., Nakagaki, H. et al. Analysis of risk factors for dental caries in infants: a comparison between urban and rural areas. Environ Health Prev Med 14, 103–110 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12199-008-0065-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12199-008-0065-6