Abstract

The production of heavy and extra-heavy oil is challenging because of the rheological properties that crude oil presents due to its high asphaltene content. The upgrading and recovery processes of these unconventional oils are typically water and energy intensive, which makes such processes costly and environmentally unfriendly. Nanoparticle catalysts could be used to enhance the upgrading and recovery of heavy oil under both in situ and ex situ conditions. In this study, the effect of the Ni-Pd nanocatalysts supported on fumed silica nanoparticles on post-adsorption catalytic thermal cracking of n-C7 asphaltenes was investigated using a thermogravimetric analyzer coupled with FTIR. The performance of catalytic thermal cracking of n-C7 asphaltenes in the presence of NiO and PdO supported on fumed silica nanoparticles was better than on the fumed silica support alone. For a fixed amount of adsorbed n-C7 asphaltenes (0.2 mg/m2), bimetallic nanoparticles showed better catalytic behavior than monometallic nanoparticles, confirming their synergistic effects. The corrected Ozawa–Flynn–Wall equation (OFW) was used to estimate the effective activation energies of the catalytic process. The mechanism function, kinetic parameters, and transition state thermodynamic functions for the thermal cracking process of n-C7 asphaltenes in the presence and absence of nanoparticles are investigated.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Currently, fossil fuels supply approximately 82 % of the world’s energy demand (Ghannam et al. 2012). The growing demand for crude oil worldwide requires the exploitation of heavy and extra-heavy crude oil deposits, which are approximately of the same order as conventional crude oil according to the International Energy Agency (Tedeschi 1991; IEA 2013). In fact, over the period 2014–2035, approximately 9 % of the cumulative upstream investment is necessary for the development of heavy and extra-heavy oil resources (IEA 2014). For the case of Colombia, heavy and extra-heavy crude oils represent about 45 % of the total local oil production, and it is expected to increase to 60 % by 2018 (Colombia Energía 2013).

The oil and gas industry has avoided the exploitation of heavy oil (HO) and extra-heavy oil (EHO) reservoirs due to the high cost of production, transportation, and refining in comparison with conventional crude oil production. However, in the last decade, the cost of oil and the increasing production of HO and EHO have altered opinions about this topic (Castaneda et al. 2014). These types of crude oil have disadvantages in their physical properties compared with light crude oil, hindering production from reservoirs. This behavior occurs because HO and EHO have extremely high asphaltene contents, which result in high viscosities and low specific gravities (Luo and Gu 2007). The chemical structures of asphaltenes are very complex. They are usually defined as the fraction of oil that is insoluble in low molecular weight n-paraffin, such as n-heptane or n-pentane, while being soluble in light aromatic hydrocarbons, such as toluene, benzene, or pyridine. The structures of asphaltenes are formed by polyaromatic cores attached to aliphatic chains containing heteroatoms, such as nitrogen, oxygen, sulfur, and metals including vanadium, iron, and nickel (Chianelli et al. 2007; Mullins et al. 2012; Mullins 2011; Groenzin and Mullins 1999, 2000). Asphaltenes also contain polar and nonpolar groups and tend to form i-mer colloids due to their polarizability and self-associative characteristics (Montoya et al. 2014; Bockrath et al. 1980; Wargadalam et al. 2002; Rosales et al. 2006; Acevedo et al. 1998; Mousavi-Dehghani et al. 2004; Sheu et al. 1994). It has been widely documented that the viscosity of heavy oil can dramatically increase due to asphaltene aggregation (Acevedo et al. 1998; Mousavi-Dehghani et al. 2004; Sheu et al. 1994).

Accordingly, several in situ techniques have been employed for enhancing HO and EHO recovery with the objective of upgrading the oil and improving its viscosity and mobility. These techniques include thermal processes, such as in situ combustion and steam-assisted gravity drainage (SAGD) (Cavallaro et al. 2008; Moore et al. 1999; Greaves et al. 2001; Kumar et al. 2011; Kapadia et al. 2010; Speight 1970; Jiang et al. 2005; Fan et al. 2004; Maity et al. 2010), and cold techniques, such as treatments using diluents like natural gas condensate (Luo et al. 2007a, b; James et al. 2008; Castro et al. 2011; Cavallaro et al. 2005). The latter (i.e., cold process) is used to improve the crude oil by dilution or destabilization, and deposition of the asphaltene components in the reservoir by injecting solvents that have a direct impact on viscosity reduction (Luo et al. 2007b; Cavallaro et al. 2005). The more frequently employed thermal techniques for heavy oil upgrading address breaking the heavier compounds of oil using combustion processes (Moore et al. 1999; Cavallaro et al. 2008), low-temperature oxidation (Xu et al. 2000; Wichert et al. 1995), aquathermolysis (Jiang et al. 2005; Fan et al. 2004; Maity et al. 2010), and pyrolysis, also called thermal cracking or thermolysis (Speight 1970; Kumar et al. 2011; Monin and Audibert 1988; Nassar et al. 2013a). However, most of these techniques do not exceed 20 %–25 % oil recovery or 50 % for the steam-assisted gravity drainage (SAGD) process (Butler 1998; Nasr et al. 2003; Hashemi et al. 2013). Nanoparticle technology has emerged as an alternative with a great potential to improve the previously mentioned techniques and increase oil recovery (Hashemi et al. 2014a, b, c; Galarraga and Pereira-Almao 2010; Hashemi et al. 2012; Franco et al. 2013a, b, 2014; Hosseinpour et al. 2014). Because of their small sizes, high surface area/volume ratios, and tunable chemical characteristics, nanoparticles have exceptional adsorptive and catalytic properties and can be employed for in situ adsorption and post-adsorption catalytic cracking of heavy hydrocarbons, such as asphaltenes (Nassar et al. 2011a, b, c, d, e, 2012a, b, 2013b, 2014; Nassar 2010; Franco et al. 2013c; Hosseinpour et al. 2014; Hashemi et al. 2014c). It has been demonstrated that with advanced research, nanoparticles can be used to sustain the heavy oil industry via the development of environmentally sound processes with cost-effective approaches. For in situ applications, previous studies have provided useful information about the catalytic effects of transition metal oxide and supported nanoparticles on asphaltene gasification (Nassar et al. 2011a, 2015a; Franco et al. 2014), pyrolysis (Nassar et al. 2012b), and oxidation (Franco et al. 2013b, 2015; Nassar et al. 2011b, c, d, e, 2012a, 2013b, 2014).

This work continues previous work (Franco et al. 2013b, 2014, 2015), and it aims at employing NiO and/or PdO nanoparticles supported on fumed silica nanoparticles for post-adsorption catalytic thermal cracking of n-C7 asphaltenes. The kinetic study of the thermal cracking of asphaltenes in the presence and absence of nanoparticles was carried out using the isoconversional method. In addition, the mechanism function, kinetic parameters, and transition state thermodynamic functions for the thermal cracking process of n-C7 asphaltenes in the presence and absence of nanoparticles are reported for the first time. This work provides potential applications of nanoparticle technology for heavy oil catalytic upgrading and recovery, which could be a viable alternative green technology.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials

A sample of “Capella” HO (Putumayo, South of Colombia) was used as the source of n-C7 asphaltenes. This HO sample has an API of 10.5° (specific gravity: 0.996; asphaltene content: 9 wt%) and viscosity of 4.7 × 105 cP at 25 °C. n-Heptane (99 %, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used as a precipitant for isolating solid virgin n-C7 asphaltenes from crude oil by following the standard procedure reported in previous studies (Franco et al. 2013b; Nassar 2010). Toluene (99.5 %, Merck KGaA, Germany) was used to prepare heavy oil model solutions. Fumed silica (S) nanoparticles were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Distilled water and salt precursors of Ni(NO3)2(6H2O) (Merck KGaA, Germany) and Pd(NO3)2 (Merck KGaA, Germany) were used for nanoparticle functionalization.

The functionalized nanoparticles were prepared following the procedure developed in a previous study (Franco et al. 2013b). Briefly, NiO and/or PdO supported on silica nanoparticles were prepared by the incipient wetness method (Ertl et al. 2008), where the support nanoparticles were exposed to the corresponding aqueous solutions of Ni(NO3)2 and/or Pd(NO3)2 followed by drying at 120 °C overnight and calcination for 6 h in air at 450 °C. The amount of NiO and/or PdO on the support was controlled to 1 wt%–2 wt% by changing the concentration of aqueous solutions of the corresponding nitrate. The functionalized nanoparticles were labeled by the initial letter of the support (S for 7 nm silica nanoparticles) followed by the symbol of the cation of the resulting metal oxide after the calcination process and the weight percentage of the precursor hydroscopic salt used. The hybrid nanomaterials obtained in this study are called supported hygroscopic salt (SHS). Thus, nanoparticles of SNiXPdY with 1 wt% PdO and 1 wt% NiO were denoted SNi1Pd1.

Table 1 lists the measured BET surface areas (S BET) and mean crystallite sizes of the nanoparticles considered in this study. The S BET was measured via nitrogen physisorption at −196 °C using an Autosorb-1 from Quantachrome after outgassing samples overnight at 140 °C under high vacuum (10−6 mbar). The mean crystal size of the nanoparticles was measured by applying the Debye-Scherrer equation to the primary XRD peak. XRD patterns were recorded with an X’Pert PRO MPD X-ray diffractometer from PANalytical using Cu Kα radiation operating at 60 kV and 40 mA with a θ/2θ goniometer. Additional information about nanoparticles characterizations can be found in previous studies (Franco et al. 2013b, 2014; Nassar et al. 2015b).

2.2 Methods

2.2.1 Adsorption experiments

Bath-mode adsorption experiments were carried out at a temperature of 25 °C using a set of 50-mL glass beakers by adding a fixed amount of nanoparticles to the heavy oil model solutions at a nanoparticle-to-solution ratio of 100 mg to 10 mL and different initial concentrations (\(C_{i}\)) of n-C7 asphaltenes and mixing for 24 h, as described elsewhere (Franco et al. 2013b, 2014, 2015). Then, the nanoparticles with the adsorbed asphaltenes were separated from the mixture by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 30 min to guarantee the maximum recovery of the material (Franco et al. 2015). After that, the nanoparticles containing adsorbed asphaltenes were dried to remove any traces of toluene. At this stage, the nanoparticles containing adsorbed asphaltenes were ready for the thermal analysis experiment. The amount of asphaltenes adsorbed \(q\) (mg of n-C7 asphaltenes/m2 dry surface area of nanoparticles) was obtained by mass balance (Franco et al. 2013b, 2014).

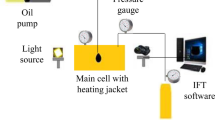

2.2.2 Thermogravimetric analysis of virgin and adsorbed n-C7 asphaltenes

The dried nanoparticles with adsorbed asphaltenes were subjected to catalytic thermal cracking at temperatures up to 800 °C in a thermogravimetric analyzer Q50 (TA Instruments, Inc., New Castle, DE) at three different heating rates of 5, 10, and 20 °C/min in an Ar atmosphere. The flow of the inert gas was kept constant at 100 cm3/min throughout the experiment. The sample mass was kept at approximately 5 mg to avoid diffusion limitations (Nassar et al. 2013a). The selected nanoparticles for TGA experiments had the same loading of asphaltenes per unit surface area of 0.2 mg/m2. The gases produced by the thermal cracking process were analyzed via Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy using an online spectrophotometer IRAffinity-1 (Shimadzu, Japan) coupled to the TGA and operating in transmission mode in the range of 4000–400 cm−1 at a resolution of 2 cm−1 with 16 scans/min (Franco et al. 2014, 2015; Nassar et al. 2015a). After the thermal cracking process, oxidation under an air flow of 20 °C/min from 100 to 800 °C was conducted to estimate the coke yield (Franco et al. 2014). All experiments were performed in duplicate to confirm reproducibility.

2.3 Theoretical considerations

2.3.1 Estimation of effective activation energy

The corrected Ozawa–Flynn–Wall equation (OFW) was used to estimate the effective activation energies; assuming that, for a constant reaction conversion, the reaction rate [Eq. (1)] is a function of the state and the temperature (Vyazovkin et al. 2011; Nassar et al. 2014).

where \(A_{\alpha }\) is the pre-exponential factor, s−1; \(E_{\alpha }\) is the effective activation energy for a constant conversion, kJ/mol; \(R\) is the ideal gas constant, J/(mol K); \(T\) is the reaction temperature, K, and \(\alpha\) is the reaction conversion as described by Eq. (2):

where \(m_{0}\) is the initial mass of the sample, \(m_{f}\) the final mass of the sample, and m t is the mass at a given temperature. Defining the heating rate as \(\beta = {\text{d}}T{/}{\text{d}}t\) and after integrating, Eq. (3) is obtained:

The right-hand side of Eq. (3) is solved via a commonly employed approach for isoconversional methods by defining \(x = - E_{\alpha } /RT\) and applying the Doyle approximation (Doyle 1961, 1965). After rearrangement, the effective activation energy at each value of \(\alpha\) can be estimated from the slope of the linear fit from the plot of \(\ln (\beta )\) against \(1/T\) according to Eq. (4) (Ozawa 1965; Flynn and Wall 1966; Nassar et al. 2014):

The error in the estimation of \(E_{\alpha }\) due to Doyle’s approximation is corrected using a correction factor as shown in Eq. (5) (Nassar et al. 2014; Opfermann and Kaisersberger 1992; Flynn 1983):

with

and

where \(T_{m}\) is the mean temperature at the determined value for the selected \(\alpha\), K.

2.3.2 Estimation of the thermodynamic parameters of the transition state functions

The thermodynamic parameters of the transition state functions, such as changes in the Gibbs free energy (\(\Delta G^{\ddag }\)), enthalpy (\(\Delta H^{\ddag }\)), and entropy (\(\Delta S^{\ddag }\)) of activation, are of importance for understanding the catalytic role of the SHS nanoparticles. A conversion of 50 % at a fixed heating rate of 5 °C/min was used for the estimation of the thermodynamic parameters at the respective temperature, \(T_{p}\) (K). Hence, \(\Delta G^{\ddag }\) can be estimated as follows:

where \(\Delta H^{\ddag }\) can be approximated to \(\Delta H^{\ddag } = E^{\ddag } - RT_{p}\), with \(E^{\ddag }\) as the effective activation energy at the selected \(T_{p}\) (Nassar et al. 2014). In addition, after rearrangement of the Arrhenius and Eyring equations (Nassar et al. 2014; Rooney 1995; Young 1966; Sestak 1984), \(\Delta S^{\ddag }\) can be estimated as follows:

where \(h\) (6.6261 × 10−34 J s) is the Planck’s constant, \(e\) (2.7183) is the Neper number, and \(k_{B}\) (1.3806 × 10−23 J/K) is Boltzmann’s constant. The pre-exponential factor \(A\) can be estimated from the intercept of the linear plots of \(\ln [g(\alpha )]\) against \(\ln (\beta )\) according to Eq. (4) (Nassar et al. 2014). The n-order kinetic expressions \((1 - \alpha )^{ - n + 1} - 1\) and \(\frac{1}{n - 1}\left( {1 - \alpha } \right)^{n}\) were used for the estimation of the best-fit chemical reaction models \(g(\alpha )\) and \(f(\alpha )\), respectively. \(n\) is the mechanism order and was estimated as the value where the slope and the \(R^{2}\) of the linear plots of \(\ln [g(\alpha )]\) against \(\ln (\beta )\) are equal to −1.0 and 1.0, respectively (Nassar et al. 2014).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Asphaltene adsorption onto fumed silica and SHS

n-C7 asphaltene adsorption on the surface area-normalized basis was higher for the SHS nanoparticles than for the fumed silica support, and it followed the order SNi1Pd1 > SNi2 > SPd2 > S (Franco et al. 2014). This result was attributed to the synergistic effects of NiO and PdO, which have different selectivities toward the asphaltene compounds. As the purpose of this study is to investigate the role of nanoparticles in the catalytic thermal cracking of adsorbed asphaltenes, we will limit our discussion on the role of the nanoparticles as nanocatalysts. Detailed discussion of the roles of the nanoparticles as adsorbents for n-C7 asphaltenes and full descriptions of the adsorption isotherms can be found in a previous study (Franco et al. 2014).

3.2 Catalytic thermal cracking of n-C7 asphaltenes

3.2.1 Rate of mass loss of n-C7 asphaltenes in the presence and absence of silica nanoparticles

Figure 1 shows the rate of mass loss of virgin n-C7 asphaltenes and n-C7 asphaltenes in the presence of silica nanoparticles in the thermal cracking reaction. As shown, virgin asphaltene decomposition started at approximately 310 °C and finished at approximately 660 °C with a maximum mass loss rate at approximately 448 °C. These findings are in very close agreement with those reported by Nassar et al. (2012b) for the pyrolysis of asphaltenes extracted from a vacuum residue from Athabasca EHO; they found that thermal decomposition occurred between 300 and 700 °C. The n-C7 asphaltenes thermal decomposition could be fractionated into three steps: (1) the breaking of intermolecular associations, loss of short alkyl chains, and weak chemical bonds such as sulfur bridges (Trejo et al. 2010) at temperatures lower than 350 °C; (2) the rupture of longer alkyl groups and the opening of the PAHs between 350 and 500 °C; and (3) coke formation at temperatures above 500 °C (Nassar et al. 2012b). The catalytic effect of the silica nanoparticles is also found in Fig. 1. The catalytic thermal decomposition of n-C7 asphaltenes in the presence of silica nanoparticles can be divided into two main regions: one from 300 to 500 °C and a second one from 500 to 800 °C. The first region corresponds to the breaking of the alkyl side chains and the PAHs. In this region, the maximum peak of the rate of mass loss was shifted to the left by approximately 40 °C, in comparison with that of virgin n-C7 asphaltenes, indicating that the reactions involved in this stage took place earlier than those for the virgin n-C7 asphaltenes. However, according to the rate of mass loss above 500 °C, it seems that some addition reactions occurred in the first stage and the decomposition of the resultant compounds took place at up to 800 °C, indicating that silica nanoparticles could lead to less coke formation in comparison to virgin n-C7 asphaltenes.

For the functionalized nanoparticles, Fig. 2 shows the plot of the rate of mass loss of monometallic SNi2 and SPd2. As shown, two peaks were found below 660 °C for both SNi2 and SPd2. For SNi2 nanoparticles, the first peak appeared near to 300 °C, and the second one (main peak) was shifted to the left by approximately 30 °C in comparison with the main peak of the virgin n-C7 asphaltenes. These results indicated that SNi2 nanoparticles had a higher catalytic effect on the n-C7 asphaltene thermal cracking than the silica support. For SPd2 nanoparticles, the first peak appeared near 210 °C, and the second one was in the same position as that for the SNi2 nanoparticles. It is worth mentioning here that the magnitude of the first peak was about one-third higher than that of the second peak, indicating that more components were decomposed in this region (the first peak). This result is in agreement with a previous work on the oxidation of n-C7 asphaltenes that showed asphaltene decomposition in the presence of SPd2 took place at temperatures near to 220 °C (Franco et al. 2013b). For both monometallic SHS, at temperatures higher than 660 °C, it can be found that some addition reactions could occur. However, with SPd2 nanoparticles, only a small peak appeared at 720 °C, and then, the rate of mass loss drop off to zero, indicating that monometallic SHS functionalized with PdO can lead to the suppression of coke formation.

Figure 3 shows the plot of the rate of mass loss for n-C7 asphaltenes in the presence of SNi1Pd1 nanoparticles. The synergistic effect of the NiO and the PdO was clearly found. Two mean peaks appeared at 220 and 300 °C, showing that the selectivity of NiO and PdO for certain components can greatly enhance the catalytic activity. In addition, a third small peak appeared at 530 °C that was associated with the decomposition of the new compounds from the addition reactions. For temperatures above 660 °C, no mass loss was observed, indicating that bimetallic nanoparticles were useful for the suppression of coke formation with a better efficiency than SPd2 nanoparticles.

3.2.2 Presence and absence of nanoparticles

The n-C7 asphaltene thermal cracking could lead to different solid and gaseous sub-products to different extents depending on the system evaluated. As the temperature increases, radical species may be stabilized to form new lighter compounds, such as hydrocarbons with lower molecular weights, CO and CO2, among others (Savage et al. 1985; Ali and Saleem 1991; Hosseinpour et al. 2014). However, the recombination of free radial species leads to addition reactions that result in changes to the chemical structures of the n-C7 asphaltenes and, therefore, result in heavier and more refractory compounds than the initial n-C7 asphaltenes (Alshareef et al. 2011; Habib et al. 2013; Sanford 1994).

The coke yield after the thermal cracking process was evaluated for the virgin n-C7 asphaltenes and the n-C7 asphaltenes in the presence of the evaluated nanoparticles. Reactions, such as addition of olefin free radicals (Gray and McCaffrey 2002), cross-linking between aromatic clusters (Habib et al. 2013), and bridging of aromatics by alkyl chains (Alshareef et al. 2011), were likely to be responsible for the formation of more refractory compounds. Figure 4 shows the results obtained for coke yield of the five evaluated samples. As shown, the presence of nanoparticles significantly reduced the coke formation compared with the virgin n-C7 asphaltenes. In the presence of S nanoparticles, the coke yield was reduced by approximately 47 % compared with the virgin asphaltenes. However, with the functionalized nanoparticles, the inhibition of coke formation was greatly enhanced, with reductions greater than 99 % for all the SHS. It is worth mentioning here that synergistic effects were also found for the bimetallic SHS SNi1Pd1, resulting in 100 % inhibition of coke formation with this material, presumably due to the inhibition of n-C7 asphaltene self-association on the nanoparticle surfaces (Franco et al. 2015).

The thermal cracking reactions of virgin n-C7 asphaltenes and n-C7 asphaltenes in the presence of SNi1Pd1 nanoparticles were selected for gaseous product analysis. Figure 5 shows the evolution of CO2, light hydrocarbons (LHC), and CH4 during the thermal cracking of n-C7 asphaltenes in (a) the absence of and (b) the presence of SNi1Pd1 nanoparticles at a fixed heating rate of 10 °C/min. As shown, the gas profile followed, to some degree, the shapes of the mass loss rate curves for the virgin n-C7 asphaltenes and the n-C7 asphaltenes with SNi1Pd1 nanoparticles, confirming the catalytic activity of the bimetallic SHS toward n-C7 asphaltene thermal decomposition. Figure 5 also showed that, in both cases, the amount of CO2 produced was higher than the production of LHC and CH4. The results are in agreement with that by Hosseinpour et al. (2014), who evaluated the pyrolysis of n-C7 asphaltenes in the presence of NiO and found that the CO2 production was higher than that of hydrocarbons. The production of CO2 could be attributed to two main oxygen sources: i) lattice oxygen from the SHS and ii) the oxygen content of the asphaltenes (Hosseinpour et al. 2014). Free carbon radicals could react with the oxygen released from O-containing functional groups in the n-C7 asphaltene structures to form CO; the CO was chemisorbed on the catalyst surface, and after reaction with the surface oxygen, it is desorbed as CO2. The oxygen content in the n-C7 asphaltene structures and the mobility of the lattice oxygen in the adsorbent structures play important roles in the stabilization of free radicals, the formation of carbon oxides and, subsequently, the suppression of coke formation. Thus, because the coke yield was minimized with SHS, one can infer that the lattice oxygen in the functionalized nanoparticles is more mobile and more prone to react than the oxygen in the support.

3.3 Estimation of the effective activation energies

The effective activation energies (\(E_{\alpha }\)) were estimated by the isoconversional OFW method. Panels a–e in Fig. 6 show the percentage of conversion as a function of temperature for (a) virgin n-C7 asphaltenes and asphaltenes in the presence of (b) fumed silica, (c) SNi2, (d) SPd2, and (e) SNi1Pd1 nanoparticles at different heating rates of 5, 10, and 20 °C/min. As shown, for all the materials, the gap between the three curves at different heating rates was almost constant, and there was no overlapping, which allows for the successful use of the OFW method avoiding the risk of the calculation with underestimated values. Taking a fixed heating rate of 10 °C/min for comparison, the catalytic effect of the nanoparticles could be found via the higher conversion at lower temperatures. For a fixed conversion of 40 %, the catalytic activity follows the order of SNi1Pd1 > SPd2 > SNi2 > S, and for all the nanoparticles, the temperature of n-C7 asphaltene decomposition was lower than that of the virgin n-C7 asphaltene decomposition.

Figure 7 shows \(E_{\alpha }\) for the thermal cracking of n-C7 asphaltenes with different nanoparticles and of the virgin n-C7 asphaltenes as a function of the degree of conversion estimated by Eq. (5). It was found that \(E_{\alpha }\) was not the same for all the conversion degrees, indicating that the n-C7 asphaltene thermal cracking was not a single-mechanism process (Nassar et al. 2014), due to different reaction paths might occur, such as aromatization, dealkylation, fragmentation, isomerization, and/or rupture of naphthene rings (Siddiqui 2010). For the virgin n-C7 asphaltenes, the activation energy varied between 117 and 195 kJ/mol, while for SNi1Pd1, \(E_{\alpha }\) ranged between 55 and 170 kJ/mol. When the conversion percentage was less than 50 %, the general trend for the effective activation energy was SNi1Pd1 ≈ SPd2 < SNi2 < S < virgin n-C7 asphaltenes. However, when the conversion percentage was above 60 %, the trend for \(E_{\alpha > 60\;\% }\) was virgin asphaltenes < SNi1Pd1 ≈ SPd2 < SNi2 ≈ S. This results might be attributed to the addition reactions mentioned above that lead to decomposition of the new compounds at temperatures higher than that for virgin n-C7 asphaltenes decomposition. It is worth mentioning that, for the thermal cracking of n-C7 asphaltenes with nanoparticles functionalized with PdO, the values of \(E_{\alpha }\) never reached the highest value of \(E_{\alpha }\) for virgin n-C7 asphaltenes, confirming that, with these nanoparticles, the addition reactions were suppressed, and there was little formation of components with larger molecular weights than the virgin n-C7 asphaltenes.

3.4 Thermodynamic parameters of the transition state functions

The kinetic parameters and thermodynamic properties of the transition state functions for the thermal cracking of n-C7 asphaltenes in the presence and absence of the nanoparticles were studied following the procedure described in Sect. 2.3 and are presented in Table 2. As shown, the values of mechanism order n ranged from 1.5 to 10 with the slope values between −1.07 and −0.97 for \(R^{2}\) = 0.99. However, it is worth mentioning that the values of \(n\) > 4 lack chemical significance and were only used as fitting parameters for the description of the kinetic equation and the estimation of the thermodynamic properties. This is because the chemical compositions and structures are very complex and can result in a series of unidentified simultaneous reactions. Additionally, different values of \(n\) imply that the thermal cracking of n-C7 asphaltenes in the presence or absence of the nanoparticles is not a single-mechanism process, highly dependent on the chemical nature of the nanoparticles. Table 2 shows that the trend of the change in the enthalpy (\(\Delta H^{\ddag }\)) of activation follows the order of virgin n-C7 asphaltenes > S > SNi2 > SPd2 > SNi1Pd1, indicating that the highest catalytic effect was obtained with the bimetallic SHS as its reduction in \(\Delta H^{\ddag }\) was highest among the evaluated systems; the same trend can be found for Gibbs free energy (\(\Delta G^{\ddag }\)). In addition, according to the negative values of the entropy \(\Delta S^{\ddag }\), it can be inferred that the entropy of the activated state is lower than that of the initial state (Nassar et al. 2014).

4 Conclusions

This study provides important insights into the effects of NiO and PdO supported on fumed silica nanoparticles on the thermal cracking of n-C7 asphaltenes. The catalytic thermal cracking process was performed using a TGA/FTIR system. The reaction kinetics were studied using the isoconversional Ozawa–Flynn–Wall (OFW) corrected method. The mechanism function, kinetic parameters, and transition state thermodynamic functions for the thermal cracking of n-C7 asphaltenes were nanoparticle dependent. PdO supported on silica nanoparticles showed better catalytic activity than NiO supported on silica nanoparticles. Nevertheless, bimetallic nanoparticles (NiO and PdO) supported on silica nanoparticles showed the highest catalytic activity. The excellent behavior of the bimetallic nanoparticles could be attributed the synergistic effects of NiO and PdO on the silica surface, which leads to higher selectivity than the independent effects of the monometallic ones. The computational kinetics study of n-C7 asphaltenes thermal cracking in the presence and absence of nanoparticles were carried out using the isoconversional method. The reaction kinetic parameters, namely, activation energy \((E_{\alpha } )\), the pre-exponential factor \((A_{\alpha } )\) and the most probable mechanism functions \(f\left( \alpha \right)\) were determined. Thermodynamic transition state parameters, namely, changes in Gibbs free energy of activation \((\Delta G^{\ddag } )\), enthalpy of activation \((\Delta H^{\ddag } )\), and entropy of activation \((\Delta S^{\ddag } )\) were also calculated through kinetic parameters. Bimetallic (NiO and PdO) supported on silica nanoparticles showed the highest catalytic activity toward n-C7 asphaltenes thermal cracking, confirmed by the lowest effective activation energy trend and lowest values of reaction temperature, \(\Delta H^{\ddag } , {\text{and }} \Delta G^{\ddag }.\) This work provides new insights into the use of nanoparticles for enhancing the in situ heavy and extra-heavy oil upgrading and recovery processes.

References

Acevedo S, Castillo J, Fernández A, et al. A study of multilayer adsorption of asphaltenes on glass surfaces by photothermal surface deformation. Relation of this adsorption to aggregate formation in solution. Energy Fuels. 1998;12(2):386–90.

Ali MF, Saleem M. Thermal decomposition of Saudi crude oil asphaltenes. Fuel Sci Technol Int. 1991;9(4):461–84.

Alshareef AH, Scherer A, Tan X, et al. Formation of archipelago structures during thermal cracking implicates a chemical mechanism for the formation of petroleum asphaltenes. Energy Fuels. 2011;25(5):2130–6.

Bockrath BC, LaCount RB, Noceti RP. Coal-derived asphaltenes: effect of phenol content and molecular weight on viscosity of solutions. Fuel. 1980;59(9):621–6.

Butler R. SAGD comes of age! J Can Pet Technol. 1998;37(07):9–12.

Castaneda LC, Munoz JA, Ancheyta J. Current situation of emerging technologies for upgrading of heavy oils. Catal Today. 2014;220:248–73.

Castro LV, Flores EA, Vazquez F. Terpolymers as flow improvers for Mexican crude oils†. Energy Fuels. 2011;25(2):539–44.

Cavallaro A, Galliano G, Sim S, et al. Laboratory investigation of an innovative solvent based enhanced recovery and in situ upgrading technique. In: Canadian international petroleum conference. Petroleum Society of Canada; 2005.

Cavallaro A, Galliano G, Moore R, et al. In situ upgrading of Llancanelo heavy oil using in situ combustion and a downhole catalyst bed. J Can Pet Technol. 2008;47(9):23–31.

Chianelli RR, Siadati M, Mehta A, et al. Self-assembly of asphaltene aggregates: synchrotron, simulation and chemical modeling techniques applied to problems in the structure and reactivity of asphaltenes. In: Mullins OC, Sheu EC, Hammami A, Marshall AG, editors. Asphaltenes, heavy oils, and petroleomics. New York: Springer; 2007.

Colombia Energía. Crudos pesados, la gran apuesta del sector. http://www.colombiaenergia.com/featured-article/crudos-pesados-la-gran-apuesta-del-sector (2013). Accessed 10 Aug 2015.

Doyle C. Synthesis and evaluation of thermally stable polymers. II. Polymer evaluation. Appl Polym Sci. 1961;5:285–92.

Doyle CD. Series approximations to the equation of thermogravimetric data. Nature. 1965;207:290–1.

Ertl G, Knözinger H, Weitkamp J. Preparation of Solid Catalysts. New York: Wiley; 2008.

Fan H, Zhang Y, Lin Y. The catalytic effects of minerals on aquathermolysis of heavy oils. Fuel. 2004;83(14):2035–9.

Flynn J. The isoconversional method for determination of energy of activation at constant heating rates: corrections for the Doyle approximation. J Therm Anal Calorim. 1983;27(1):95–102.

Flynn JH, Wall LA. A quick, direct method for the determination of activation energy from thermogravimetric data. J Polym Sci C Polym Lett. 1966;4(5):323–8.

Franco C, Patiño E, Benjumea P, et al. Kinetic and thermodynamic equilibrium of asphaltenes sorption onto nanoparticles of nickel oxide supported on nanoparticulated alumina. Fuel. 2013a;105:408–14.

Franco CA, Montoya T, Nassar NN, et al. Adsorption and subsequent oxidation of Colombian asphaltenes onto nickel and/or palladium oxide supported on fumed silica nanoparticles. Energy Fuels. 2013b;27(12):7336–47.

Franco CA, Nassar NN, Ruiz MA, et al. Nanoparticles for inhibition of asphaltenes damage: adsorption study and displacement test on porous media. Energy Fuels. 2013c;27(6):2899–907. doi:10.1021/ef4000825.

Franco CA, Nassar NN, Montoya T, Cortés FB. NiO and PdO supported on fumed silica nanoparticles for adsorption and catalytic steam gasification of Colombian C7 asphaltenes. In: Ambrosio J, editor. Handbook on Oil Production Research. New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2014.

Franco CA, Nassar NN, Montoya T, et al. Influence of asphaltene aggregation on the adsorption and catalytic behavior of nanoparticles. Energy Fuels. 2015;29(3):1610–21.

Galarraga CE, Pereira-Almao P. Hydrocracking of Athabasca bitumen using submicronic multimetallic catalysts at near in-reservoir conditions. Energy Fuels. 2010;24(4):2383–9.

Ghannam MT, Hasan SW, Abu-Jdayil B, et al. Rheological properties of heavy & light crude oil mixtures for improving flowability. J Pet Sci Eng. 2012;81:122–8.

Gray MR, McCaffrey WC. Role of chain reactions and olefin formation in cracking, hydroconversion, and coking of petroleum and bitumen fractions. Energy Fuels. 2002;16(3):756–66.

Greaves M, Saghr A, Xia T, et al. THAI-new air injection technology for heavy oil recovery and in situ upgrading. J Can Pet Technol. 2001;40(3):38–47.

Groenzin H, Mullins OC. Asphaltene molecular size and structure. J Phys Chem A. 1999;103(50):11237–45.

Groenzin H, Mullins OC. Molecular size and structure of asphaltenes from various sources. Energy Fuels. 2000;14(3):677–84.

Habib FK, Diner C, Stryker JM, et al. Suppression of addition reactions during thermal cracking using hydrogen and sulfided iron catalyst. Energy Fuels. 2013;27(11):6637–45.

Hashemi R, Nassar NN, Pereira-Almao P. Transport behavior of multimetallic ultradispersed nanoparticles in an oil-sands-packed bed column at a high temperature and pressure. Energy Fuels. 2012;26(3):1645–55.

Hashemi R, Nassar NN, Pereira-Almao P. Enhanced heavy oil recovery by in situ prepared ultradispersed multimetallic nanoparticles: a study of hot fluid flooding for Athabasca bitumen recovery. Energy Fuels. 2013;27(4):2194–201.

Hashemi R, Nassar NN, Pereira-Almao P. In situ upgrading of athabasca bitumen using multimetallic ultra-dispersed nanocatalysts in an oil-sands-packed bed column: Part 1, produced liquid quality enhancement. Energy Fuels. 2014a;28(2):1338–50.

Hashemi R, Nassar NN, Pereira-Almao P. In situ upgrading of Athabasca bitumen using multimetallic ultradispersed nanocatalysts in an oil sands packed-bed column: Part 2, solid analysis and gaseous product distribution. Energy Fuels. 2014b;28(2):1351–61.

Hashemi R, Nassar NN, Pereira-Almao P. Nanoparticle technology for heavy oil in situ upgrading and recovery enhancement: opportunities and challenges. Appl Energy. 2014c;133:374–87.

Hosseinpour N, Mortazavi Y, Bahramian A, et al. Enhanced pyrolysis and oxidation of asphaltenes adsorbed onto transition metal oxides nanoparticles towards advanced in situ combustion EOR processes by nanotechnology. Appl Catal A. 2014;477:159–71.

IEA. Resources to Reserves 2013.

IEA. World Energy Investment Outlook. 2014.

James L, Rezaei N, Chatzis I. VAPEX, warm VAPEX and hybrid VAPEX: the state of enhanced oil recovery for in situ heavy oils in Canada. J Can Pet Technol. 2008;47(4):12–8.

Jiang S, Liu X, Liu Y, et al. editors. In Situ Upgrading Heavy Oil by Aquathermolytic Treatment Under Steam Injection Conditions. In: SPE international symposium on oilfield chemistry. Society of Petroleum Engineers; 2005.

Kapadia PR, Kallos M, Gates ID, editors. A comprehensive kinetic theory to model thermolysis aquathermolysis gasification combustion and oxidation of athabasca bitumen. In: SPE improved oil recovery symposium. Society of Petroleum Engineers; 2010.

Kumar J, Fusetti L, Corre B, editors. Modeling in-situ upgrading of extraheavy oils/tar sands by subsurface pyrolysis. In: Canadian unconventional resources conference. Society of Petroleum Engineers; 2011.

Luo P, Gu Y. Effects of asphaltene content on the heavy oil viscosity at different temperatures. Fuel. 2007;86(7):1069–78.

Luo P, Yang C, Gu Y. Enhanced solvent dissolution into in situ upgraded heavy oil under different pressures. Fluid Phase Equilib. 2007a;252(1):143–51.

Luo P, Yang C, Tharanivasan A, et al. In situ upgrading of heavy oil in a solvent-based heavy oil recovery process. J Can Pet Technol. 2007b;46(9):37–43.

Maity S, Ancheyta J, Marroquín G. Catalytic aquathermolysis used for viscosity reduction of heavy crude oils: a review. Energy Fuels. 2010;24(5):2809–16.

Monin J, Audibert A. Thermal cracking of heavy-oil/mineral matrix systems. SPE Reserv Eng. 1988;3(04):1243–50.

Montoya T, Coral D, Franco CA, et al. A novel solid-liquid equilibrium model for describing the adsorption of associating asphaltene molecules onto solid surfaces based on the “Chemical Theory”. Energy Fuels. 2014;. doi:10.1021/ef501020d.

Moore R, Laureshen C, Mehta S, et al. A downhole catalytic upgrading process for heavy oil using in situ combustion. J Can Pet Technol. 1999;38(13):1–8.

Mousavi-Dehghani S, Riazi M, Vafaie-Sefti M, et al. An analysis of methods for determination of onsets of asphaltene phase separations. J Pet Sci Eng. 2004;42(2):145–56.

Mullins OC. The asphaltenes. Annu Rev Anal Chem. 2011;4:393–418.

Mullins OC, Sabbah H, Jl Eyssautier, et al. Advances in asphaltene science and the Yen-Mullins model. Energy Fuels. 2012;26(7):3986–4003.

Nasr T, Beaulieu G, Golbeck H, et al. Novel expanding solvent-SAGD process ES-SAGD. J Can Pet Technol. 2003;42(1):13–6.

Nassar NN. Asphaltene adsorption onto alumina nanoparticles: kinetics and thermodynamic studies. Energy Fuels. 2010;24(8):4116–22. doi:10.1021/ef100458g.

Nassar NN, Hassan A, Pereira-Almao P. Application of nanotechnology for heavy oil upgrading: catalytic steam gasification/cracking of asphaltenes. Energy Fuels. 2011a;25(4):1566–70.

Nassar NN, Hassan A, Pereira-Almao P. Comparative oxidation of adsorbed asphaltenes onto transition metal oxide nanoparticles. Colloids Surf, A. 2011b;384(1):145–9.

Nassar NN, Hassan A, Pereira-Almao P. Effect of surface acidity and basicity of aluminas on asphaltene adsorption and oxidation. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2011c;360(1):233–8.

Nassar NN, Hassan A, Pereira-Almao P. Effect of the particle size on asphaltene adsorption and catalytic oxidation onto alumina particles. Energy Fuels. 2011d;25(9):3961–5.

Nassar NN, Hassan A, Pereira-Almao P. Metal oxide nanoparticles for asphaltene adsorption and oxidation. Energy Fuels. 2011e;25(3):1017–23.

Nassar NN, Hassan A, Carbognani L, et al. Iron oxide nanoparticles for rapid adsorption and enhanced catalytic oxidation of thermally cracked asphaltenes. Fuel. 2012a;95:257–62.

Nassar NN, Hassan A, Pereira-Almao P. Thermogravimetric studies on catalytic effect of metal oxide nanoparticles on asphaltene pyrolysis under inert conditions. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2012b;110(3):1327–32.

Nassar NN, Hassan A, Luna G, et al. Comparative study on thermal cracking of Athabasca bitumen. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2013a;114(2):465–72.

Nassar NN, Hassan A, Luna G, et al. Kinetics of the catalytic thermo-oxidation of asphaltenes at isothermal conditions on different metal oxide nanoparticle surfaces. Catal Today. 2013b;207:127–32.

Nassar NN, Hassan A, Vitale G. Comparing kinetics and mechanism of adsorption and thermo-oxidative decomposition of Athabasca asphaltenes onto TiO2, ZrO2, and CeO2 nanoparticles. Appl Catal A. 2014;484:161–71.

Nassar NN, Franco CA, Montoya T, et al. Effect of oxide support on Ni–Pd bimetallic nanocatalysts for steam gasification of n-C7 asphaltenes. Fuel. 2015a;156:110–20.

Nassar NN, Betancur S, Acevedo S, et al. Development of a population balance model to describe the influence of shear and nanoparticles on the aggregation and fragmentation of asphaltene aggregates. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2015b;54(33):8201–11.

Opfermann J, Kaisersberger E. An advantageous variant of the Ozawa-Flynn-Wall analysis. Thermochim Acta. 1992;203:167–75.

Ozawa T. A new method of analyzing thermogravimetric data. Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan. 1965;38(11):1881–6.

Rooney JJ. Eyring transition-state theory and kinetics in catalysis. J Mol Catal A. 1995;96(1):L1–3.

Rosales S, Machín I, Sánchez M, et al. Theoretical modeling of molecular interactions of iron with asphaltenes from heavy crude oil. J Mol Catal A. 2006;246:146–53.

Sanford EC. Molecular approach to understanding residuum conversion. Ind Eng Chem Res. 1994;33(1):109–17.

Savage PE, Klein MT, Kukes SG. Asphaltene reaction pathways. 1. Thermolysis. Ind Eng Chem Process Des Dev. 1985;24(4):1169–74.

Sestak J. Thermodynamical properties of solids. Prague: Academia; 1984.

Sheu EY, Shields MB, Storm DA. Viscosity of base-treated asphaltene solutions. Fuel. 1994;73(11):1766–71.

Siddiqui MN. Catalytic pyrolysis of Arab Heavy residue and effects on the chemistry of asphaltene. J Anal Appl Pyrol. 2010;89(2):278–85.

Speight J. Thermal cracking of Athabasca bitumen, Athabasca asphaltenes, and Athabasca deasphalted heavy oil. Fuel. 1970;49(2):134–45.

Tedeschi M., editor. Reserves and production of heavy crude oil and natural bitumen. In: 13th world petroleum congress. World Petroleum Congress; 1991.

Trejo F, Rana MS, Ancheyta J. Thermogravimetric determination of coke from asphaltenes, resins and sediments and coking kinetics of heavy crude asphaltenes. Catal Today. 2010;150(3):272–8.

Vyazovkin S, Burnham AK, Criado JM, Pérez-Maqueda LA, et al. ICTAC Kinetics Committee recommendations for performing kinetic computations on thermal analysis data. Thermochim Acta. 2011;520(1):1–19.

Wargadalam VJ, Norinaga K, Iino M. Size and shape of a coal asphaltene studied by viscosity and diffusion coefficient measurements. Fuel. 2002;81(11):1403–7.

Wichert G, Okazawa N, Moore R, et al editors. In-situ upgrading of heavy oils by low-temperature oxidation in the presence of caustic additives. In: International heavy oil symposium; 1995.

Xu HH, Okazawa N, Moore R, et al. editors. In situ upgrading of heavy oil. In: Canadian international petroleum conference. Petroleum Society of Canada; 2000.

Young DA. Decomposition of solids. Oxford: Pergamon; 1966.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge COLCIENCIAS, ECOPETROL S.A., and Universidad Nacional de Colombia for the support provided in Agreement No. 264 of 2013 and the Cooperation Agreement 04 of 2013, respectively. The authors are also grateful to the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) and the Department of Chemical and Petroleum Engineering at the Schulich School of Engineering at the University of Calgary.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Edited by Xiu-Qin Zhu

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Montoya, T., Argel, B.L., Nassar, N.N. et al. Kinetics and mechanisms of the catalytic thermal cracking of asphaltenes adsorbed on supported nanoparticles. Pet. Sci. 13, 561–571 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12182-016-0100-y

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12182-016-0100-y