Abstract

Background

It is not known whether various forms of emotion regulation are differentially related to cardiovascular disease risk.

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to assess whether antecedent and response-focused emotion regulation would have divergent associations with likelihood of developing cardiovascular disease.

Methods

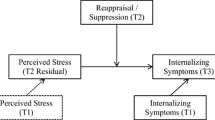

Two emotion regulation strategies were examined: reappraisal (antecedent-focused) and suppression (response-focused). Cardiovascular disease risk was assessed with a validated Framingham algorithm that estimates the likelihood of developing CVD in 10 years. Associations were assessed among 373 adults via multiple linear regression. Pathways and gender-specific associations were also considered.

Results

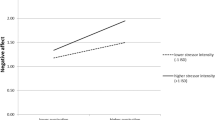

One standard deviation increases in reappraisal and suppression were associated with 5.9 % lower and 10.0 % higher 10-year cardiovascular disease risk, respectively, in adjusted analyses.

Conclusions

Divergent associations of antecedent and response-focused emotion regulation with cardiovascular disease risk were observed. Effective emotion regulation may promote cardiovascular health.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2011 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011; 123: e18-e209.

Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2010 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010; 121: e46-e215.

Miller G, Chen E, Cole SW. Health psychology: Developing biologically plausible models linking the social world to physical health. Annu Rev Psychol. 2009; 60: 501-524.

Everson-Rose SA, Lewis TT. Psychosocial factors and cardiovascular disease. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005; 26: 469-500.

Kobau R, Seligman MEP, Peterson C, et al. Mental health promotion in public health: Perspectives and strategies from positive psychology. Am J Public Health. 2011; 101: e1-e9.

Boehm JK, Kubzansky LD. The heart’s content: The association between positive psychological well-being and cardiovascular health. Psychol Bull. 2012. doi:10.1037/a0027448.

Gross JJ, John OP. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships and well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003; 85: 348-362.

John OP, Gross JJ. Healthy and unhealthy emotion regulation: Personality processes, individual differences, and life span development. J Pers. 2004; 72: 1301-1334.

Gross JJ. Emotion regulation in adulthood: Timing is everything. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2001; 10: 214-219.

Appleton AA, Kubzansky LD. Emotion regulation and cardiovascular disease risk. In: Gross JJ, ed. Hanbook of Emotion Regulation. 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2014.

Consedine NS, Magai C, Bonanno GA. Moderators of the emotion inhibition-health relationship: A review and research agenda. Rev Gen Psychol. 2002; 6: 204-228.

Appleton AA, Buka SL, Loucks EB, Gilman SE, Kubzansky LD. Divergent associations of adaptive and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies with inflammation. Health Psychol. 2013; 13: 748-756.

Rozanski A, Kubzansky LD. Psychologic functioning and physical health: A paradigm of flexibility. Psychosom Med. 2005; 67: S47-S53.

Kubzansky LD, Park N, Peterson C, Vokonas P, Sparrow D. Healthy psychological functioning and incident coronary heart disease: The importance of self-regulation. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 2011; 68: 400-408.

Kinnunen M, Kokkonen M, Kaprio J, Pulkkinen L. The associations of emotion regulation and dysregulation with the metabolic syndrome factor. J Psychosom Res. 2005; 58: 513-521.

C Reactive Protein Coronary Heart Disease Genetics Collaboration. Association between C reactive protein and coronary heart disease: Mendelian randomisation analysis based on individual participant data. BMJ. 2011; 342: 1-8.

Danesh D, Wheeler JG, Hirschfield GM, et al. C-reactive protein and other circulating markers of inflammation in the prediction of coronary heart disease. New Engl J Med. 2004; 350: 1387-1397.

Pearson TA, Mensah GA, Alexander RW, et al. Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: Application to clinical and public health practice. A statement for healthcare professionals from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2003; 107: 499-511.

Elliott P, Chambers JC, Zhang W, et al. Genetic loci associated with c-reactive protein levels and risk of coronary heart disease. JAMA. 2009; 302: 37-48.

Appleton AA, Loucks EB, Buka SL, Rimm E, Kubzansky LD. Childhood emotional functioning and the developmental origins of cardiovascular disease risk. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013; 67: 405-411.

Thurston RC, Kubzansky LD. Multiple sources of psychosocial disadvantage and risk of coronary heart disease. Psychosom Med. 2007; 69: 748-755.

Moller-Leimkuhler A. Higher comorbidity of depression and cardiovascular disease in women: A biopsychosocial perspective. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2010; 11: 922-933.

Lazarus RS. Emotion and Adaptation. New York: Oxford University Press; 1991.

Calkins SD, Hill A. Caregiver influences on emerging emotion regulation: Biological and environmental transactions in early development. In: Gross JJ, ed. Handbook of Emotion Regulation. New York: The Guilford Press; 2007: 229-248.

Thompson R. Family influences on emotion regulation. In: Gross JJ, ed. Handbook of Emotion Regulation. 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2014.

Rothbart M, Posner M. Temperament and emotion regulation. In: Gross JJ, ed. Handbook of Emotion Regulation. 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2014.

Shonkoff JP, Phillips DA, eds. From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000.

Hart CL, Taylor MD, Davey Smith G, et al. Childhood IQ and cardiovascular disease in adulthood: Prospective observational study linking the Scottish Mental Survey 1932 and the Midspan studies. Soc Sci Med. 2004; 59: 2131-2138.

Pollitt RA, Rose KM, Kaufman JS. Evaluating the evidence for models of life course socioeconomic factors and cardiovascular outcomes: A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2005; 5: 7.

Berenson GS, Srnivasan SR. Cardiovascular risk factors in youth with implications for aging: The Bogalusa heart study. Neurobiol Aging. 2005; 26: 303-307.

D’Agostino RB, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008; 117: 742-753.

Broman SH, Nichols PI, Kennedy WA. Preschool IQ: Prenatal and Early Developmental Correlates. New York: Hallstead Press; 1975.

Niswander KR, Gordon M. The Women and Their Pregnancies. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1972.

Almeida ND, Loucks EB, Kubzansky LD, et al. Quality of parental emotional care and calculated risk for coronary heart disease. Psychosom Med. 2010; 72: 148-155.

Allain CC, Poon LS, Chan CS, Richmond W, Fu PC. Enzymatic determination of total serum cholesterol. Clin Chem. 1974; 20: 470-475.

Rafai N, Cole TG, Iannotti E, et al. Assessment of interlaboratory performance in external proficiency testing programs with a direct HDL-cholesterol assay. Clin Chem. 1998; 44: 1452-1458.

Mattu GS, Heran BS, Wright JM. Overall accuracy of the BpTRU - an automated electronic blood pressure device. Blood Press Monit. 2004; 9: 47-52.

Wechsler D. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children. New York: The Psychological Corporation; 1949.

Myrianthopoulos N, French K. An application of the U.S. Bureau of the Census socioeconomic index to a large, diversified patient population. Soc Sci Med. 1968; 2: 283-299.

CDC: Fact Sheets - Alcohol Use and Health. Retrieved 9/12/13, 2013 from http://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/fact-sheets/alcohol-use.htm.

Willett WC. Nutritional Epidemiology. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998.

Michaud DS, Skinner HG, Wu K, et al. Dietary patterns and pancreatic cancer risk in men and women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005; 97: 518-524.

UCLA Academic Technology Services Statistical Consulting Group: Introduction to SAS. 2011.

Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986; 51: 1173-1182.

Kramer HC, Kiernan M, Essex M. How and why criteria defining moderators and mediators differ between the Baron & Kenny and MacArthur approachs. Health Psychol. 2008; 27: S101-S108.

Gross JJ, Levenson RW. Emotion suppression: Physiology, self-report, and expressive behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1993; 64: 970-986.

Gross JJ, Levenson RW. Hiding feelings: The acute effects of inhibiting negative and positive emotion. J Abnorm Psychol. 1997; 106: 95-103.

Black PH, Garbutt LD. Stress, inflammation and cardiovascular disease. J Psychosom Res. 2002; 52: 1-23.

Suls J, Bunde J. Anger, anxiety, and depression as risk factors for cardiovascular disease: The problems and implications of overlapping affective dispositions. Psychol Bull. 2005; 131: 260-300.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Aging grant AG023397, National Institutes of Health Transdisciplinary Tobacco Use Research Center (TTURC) Award (P50 CA084719) by the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Dr. Appleton was supported by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute Training Grant at the Harvard School of Public Health (T32 HL098048), and the Quantitative Biomedical Sciences training program at Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth (R25 CA134286).

Authors’ Statement of Conflict of Interest and Adherence to Ethical Standards

Authors Appleton, Loucks, Buka, and Kubzansky declare that they have no conflict of interest. All procedures, including the informed consent process, were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Appleton, A.A., Loucks, E.B., Buka, S.L. et al. Divergent Associations of Antecedent- and Response-Focused Emotion Regulation Strategies with Midlife Cardiovascular Disease Risk. ann. behav. med. 48, 246–255 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-014-9600-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-014-9600-4