Abstract

Background

Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) is an important aspect of well-being that may improve with health behavior interventions. However, health behavior change is difficult with pressure to maintain status quo.

Purpose

This report examines the effects of two lifestyle interventions and an advice-only condition on HRQOL. Effects of meeting behavioral goals and weight loss also were examined.

Methods

Participants were 295 men and 467 women (34% African American) with pre-hypertension or stage 1 hypertension from the PREMIER trial. HRQOL was assessed by the Short Form-36. Participants were assigned randomly to (1) advice only (ADVICE), (2) established guidelines for blood pressure control (EST), or (3) established guidelines plus the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) dietary pattern (EST + DASH).

Results

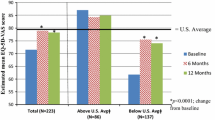

Assignment to EST resulted in improvement in three HRQOL subscales at 6 months and one at 18 months relative to ADVICE. EST + DASH improved in two subscales at 6 and 18 months compared with ADVICE. Across conditions, total fat, saturated fat, fruit, and vegetable intake change, along with ≥4-kg weight loss, resulted in HRQOL improvements at 6 and 18 months. No improvement was found for change in physical activity, and only a few HRQOL subscales were associated with change in sodium and low-fat dairy intake.

Conclusions

Intensive lifestyle interventions can result in improvements in HRQOL. Change in dietary intake and weight loss is also important.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC. Health-related quality-of-life measures—United States, 1993. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1995; 44: 195–200.

O’Loughlin C, Murphy NF, Conlon C, O’Donovan A, Ledwidge M, McDonald K. Quality of life predicts outcome in a heart failure disease management program. Int J Cardiol. 2010; 139: 60–67.

Steinberg JS, Joshi S, Schron EB, Powell J, Hallstrom A, McBurnie M. Psychosocial status predicts mortality in patients with life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias. Heart Rhythm. 2008; 5: 361–365.

Corle DK, Sharbaugh C, Mateski DJ et al. Self-rated quality of life measures: Effect of change to a low-fat, high-fiber, fruit and vegetable enriched diet. Ann Behav Med. 2001; 23: 198–207.

Steptoe A, Perkins-Porras L, Hilton S, Rink E, Cappuccio FP. Quality of life and self-rated health in relation to changes in fruit and vegetable intake and in plasma vitamins C and E in a randomised trial of behavioural and nutritional education counselling. Br J Nutr. 2004; 92: 177–184.

Block G, Sternfeld B, Block CH et al. Development of Alive! (A Lifestyle Intervention Via Email), and its effect on health-related quality of life, presenteeism, and other behavioral outcomes: Randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2008; 10: e43.

Qian Y, Zhang J, Lin Y et al. A tailored target intervention on influence factors of quality of life in Chinese patients with hypertension. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2009; 31: 71–82.

Ory M, Resnick B, Jordan PJ et al. Screening, safety, and adverse events in physical activity interventions: Collaborative experiences from the behavior change consortium. Ann Behav Med. 2005; 29 Suppl: 20–28.

Goodrich DE, Larkin AR, Lowery JC, Holleman RG, Richardson CR. Adverse events among high-risk participants in a home-based walking study: A descriptive study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2007; 4: 20.

Muldoon MF, Manuck SB, Matthews KA. Lowering cholesterol concentrations and mortality: A quantitative review of primary prevention trials. BMJ. 1990; 301: 309–314.

Smith-Warner SA, Elmer PJ, Tharp TM et al. Increasing vegetable and fruit intake: Randomized intervention and monitoring in an at-risk population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000; 9: 307–317.

Svetkey LP, Harsha DW, Vollmer WM et al. Premier: A clinical trial of comprehensive lifestyle modification for blood pressure control: Rationale, design and baseline characteristics. Ann Epidemiol. 2003; 13: 462–471.

Appel LJ, Champagne CM, Harsha DW et al. Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on blood pressure control: Main results of the PREMIER clinical trial. JAMA. 2003; 289: 2083–2093.

Svetkey LP, Erlinger TP, Vollmer WM et al. Effect of lifestyle modifications on blood pressure by race, sex, hypertension status, and age. J Hum Hypertens. 2005; 19: 21–31.

Elmer PJ, Obarzanek E, Vollmer WM et al. Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on diet, weight, physical fitness, and blood pressure control: 18-Month results of a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006; 144: 485–495.

Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: The JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003; 289: 2560–2572.

Hays RD, Sherbourne CD, Mazel RM. The RAND 36-Item Health Survey 1.0. Health Econ. 1993; 2: 217–227.

Ware JE, Jr., Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992; 30: 473–483.

Stewart AL, Greenfield S, Hays RD et al. Functional status and well-being of patients with chronic conditions. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1989; 262: 907–913.

Corica F, Corsonello A, Apolone G, Lucchetti M, Melchionda N, Marchesini G. Construct validity of the Short Form-36 Health Survey and its relationship with BMI in obese outpatients. Obesity. 2006; 14: 1429–1437.

McHorney CA, Ware JE, Jr., Lu JF, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med Care. 1994; 32: 40–66.

Ware JE, Konsinski M, Seller SD. SF-36 physical and mental health summary scales: A user manual. Boston: The Health Institute, 1994.

Blair SN, Haskell WL, Ho P et al. Assessment of habitual physical activity by a seven-day recall in a community survey and controlled experiments. Am J Epidemiol. 1985; 122: 794–804.

Sallis JF, Haskell WL, Wood PD et al. Physical activity assessment methodology in the Five-City Project. Am J Epidemiol. 1985; 121: 91–106.

Schakel SF. Maintaining a nutrient database in a changing marketplace: Keeping pace with changing food products - A research perspective. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2001; 14, 315–322.

The sixth report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Arch Intern Med. 1997; 157: 2413–2446.

Appel LJ, Moore TJ, Obarzanek E et al. A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. DASH Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1997; 336: 1117–1124.

Funk KL, Elmer PJ, Stevens VJ et al. PREMIER—A Trial of Lifestyle Interventions for Blood Pressure Control: Intervention Design and Rationale. Health Promot Pract. 2008; 9: 271–280.

Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis. Current Direction Psychological Science. 1992; 1: 98–101.

Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin. 1992; 112: 155–159.

Toobert DJ, Glasgow RE, Strycker LA et al. Biologic and quality-of-life outcomes from the Mediterranean Lifestyle Program: A randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 2003; 26: 2288–2293.

Plaisted CS, Lin PH, Ard JD, McClure ML, Svetkey LP. The effects of dietary patterns on quality of life: A substudy of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension trial. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999; 99: S84–S89.

Young DR, Vollmer WM, King AC et al. Can individuals meet multiple physical activity and dietary behavior goals? Am J Health Behav. 2009; 33: 277–286.

Brown DW, Balluz LS, Heath GW et al. Associations between recommended levels of physical activity and health-related quality of life. Findings from the 2001 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey. Prev Med. 2003; 37: 520–528.

Wendel-Vos GC, Schuit AJ, Tijhuis MA, Kromhout D. Leisure time physical activity and health-related quality of life: Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations. Qual Life Res. 2004; 13: 667–677.

Samsa GP, Kolotkin RL, Williams GR, Nguyen MH, Mendel CM. Effect of moderate weight loss on health-related quality of life: An analysis of combined data from 4 randomized trials of sibutramine vs placebo. Am J Manag Care. 2001; 7: 875–883.

Fontaine KR, Barofsky I, Bartlett SJ, Franckowiak SC, Andersen RE. Weight loss and health-related quality of life: Results at 1-year follow-up. Eat Behav. 2004; 5: 85–88.

Blissmer B, Riebe D, Dye G, Ruggiero L, Greene G, Caldwell M. Health-related quality of life following a clinical weight loss intervention among overweight and obese adults: Intervention and 24 month follow-up effects. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006; 4: 43.

Kaukua J, Pekkarinen T, Sane T, Mustajoki P. Health-related quality of life in obese outpatients losing weight with very-low-energy diet and behaviour modification—a 2-y follow-up study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003; 27: 1233–1241.

Fontaine KR, Barofsky I. Obesity and health-related quality of life. Obes Rev. 2001; 2: 173–182.

Elavsky S, McAuley E, Motl RW et al. Physical activity enhances long-term quality of life in older adults: Efficacy, esteem, and affective influences. Ann Behav Med. 2005; 30: 138–145.

National Center for Health Statistics. Chartbook on the Health of Americans. Hyattsville: National Center for Health Statistics, 2008.

Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG, Karvouni A, Kouri I, Ioannidis JP. Reporting and interpretation of SF-36 outcomes in randomised trials: Systematic review. BMJ. 2009; 338: a3006.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This work was supported by NIH grants UO1 HL60570, UO1 HL60571, UO1 60573, UO1 HL60574, and UO1 HL62828. We thank Dr. Chuhe Chen and Ms. Gayle Meltesen for conducting the statistical analyses, and the participants from all the clinical centers for participating in the trial.

About this article

Cite this article

Young, D.R., Coughlin, J., Jerome, G.J. et al. Effects of the PREMIER Interventions on Health-Related Quality of Life. ann. behav. med. 40, 302–312 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-010-9220-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-010-9220-6