Abstract

Background

Popular theories of health behavior have often been criticized for neglecting an affective component to behavioral engagement.

Purpose

This study reviewed affective judgment (AJ) constructs employed in physical activity research to assess the relationship with behavior. Studies were eligible if they included: (a) a measure of physical activity; (b) a distinct measure of AJ (e.g., affective attitude, enjoyment, intrinsic motivation); and (c) involved participants with a mean age of 18 years or older.

Methods

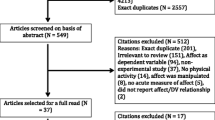

Literature searches were concluded in September, 2009 among five key search engines. This search yielded a total of 10,631 potentially relevant records; of these, 102 passed the eligibility criteria. Random effects meta-analysis procedures with correction for sampling and measurement bias were employed in the analysis.

Results

Articles were published between 1989 and 2009, with sample sizes ranging from 15 to 6,739. Of the studies included, 82 were correlational and 20 were experimental, yielding 114 independent samples. The majority of the correlational samples reported a significant positive correlation between AJ and physical activity (83 out of 85), with a summary r of 0.42 (95% CI 0.37 to 0.46) that was invariant across the measures employed, study quality, population sampled and cultural variables. Experimental studies demonstrated that persuasive, information-based, and self-regulatory interventions failed to change AJ; by contrast, environmental and experiential interventions showed promise in their capability to influence AJ.

Conclusions

The results point to a medium-effect size relationship between AJ and physical activity. Interventions that change AJ are scarce despite their potential for changing physical activity. Future experimental work designed to evaluate the causal impact of AJ on physical activity is required.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Warburton DER, Katzmarzyk P, Rhodes RE, Shephard RJ. Evidence-informed physical activity guidelines for Canadian adults. Applied Physiology, Nutrition and Metabolism. 2007; 32: S16–S68.

Bouchard C, Shephard RJ, Stephens T. The consensus statement. In: Bouchard C, Shephard RJ, Stephens T, eds. Physical activity fitness and health: International proceedings and consensus statement. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 1994: 9–76.

Canadian Fitness and Lifestyle Research Institute. 2002 Physical Activity Monitor. 2002 [cited 2004 August]; Available from: http://www.cflri.ca/cflri/pa/surveys/2002survey/2002survey.html.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Prevalence of physical activity, including lifestyle activities among adults—United States, 2000–2001. Morb Mort Wkly Rep. 2003; 15: 764–769.

Baranowski T, Anderson C, Carmack C. Mediating variable framework in physical activity interventions: How are we doing? How might we do better? Am J Prev Med. 1998; 15: 266–297.

Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. 1997; 12: 38–48.

Bandura A. Health promotion from the perspective of social cognitive theory. Psychol Health. 1998; 13: 623–649.

Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991; 50: 179–211.

Stokols D. Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. Am J Health Promot. 1996; 10: 282–298.

Lewis BA, Marcus B, Pate RR, Dunn AL. Psychosocial mediators of physical activity behavior among adults and children. Am J Prev Med. 2002; 23(2S): 26–35.

Symons Downs D, Hausenblas HA. Exercise behavior and the theories of reasoned action and planned behavior: A meta-analytic update. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2005; 2: 76–97.

Hillsdon M, Foster C, Naidoo B, Crombie H. The effectiveness of public health interventions for increasing physical activity among adults: a review of reviews. UK: Health Development Agency; 2004.

Rhodes RE, Pfaeffli LA. Mediators of behaviour change among adult non-clinical populations: A review update. Annals Behav Med. 2009; 37: s85.

Duncan M, Spence JC, Mummery WK. Perceived environment and physical activity: A meta-analysis of selected environmental characteristics. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2005 [cited 2; Available from: http://www.ijbnpa.org/content/2/1/11.

Blanchard CM, Fortier MS, Sweet SN, et al. Explaining physical activity levels from a self-efficacy perspective: The physical activity counselling trial. Annals Behav Med. 2007; 34: 323–328.

Lowe R, Eves F, Carroll D. The influence of affective and instrumental beliefs on exercise intentions and behavior: A longitudinal analysis. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2002; 32: 1241–1252.

Kimiecik JC, Harris AT. What is enjoyment? A conceptual/definitional analysis with implications for sport and exercise psychology. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 1996; 18: 247–263.

Kendzierski D, DeCarlo KJ. Physical activity enjoyment scale: Two validation studies. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 1991; 13: 50–64.

Kiviniemi MT, Voss-Humke AM, Seifert AL. How do I feel about the behavior? The interplay of affective associations with behaviors and cognitive beliefs as influences on physical activity behavior. Health Psychology: Official Journal Of The Division Of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2007; 26(2): 152–158.

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Transtheoretical therapy: Toward a more integrative model of change. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice. 1982; 19: 276–288.

Rosenstock IM. Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Educ Monogr. 1974; 2: 1–9.

French DP, Sutton S, Hennings SJ, et al. The importance of affective beliefs and attitudes in the theory of planned behavior: Predicting intention to increase physical activity. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2005; 35: 1824–1848.

Lawton R, Conner M, McEachan R. Desire or reason: Predicting health behaviors from affective and cognitive attitudes. Health Psychol. 2009; 28: 56–65.

Rhodes RE, Courneya KS. Investigating multiple components of attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control: An examination of the theory of planned behavior in the exercise domain. Br J Soc Psychol. 2003; 42: 129–146.

Kraft P, Rise J, Sutton S. Perceived difficulty in the theory of planned behaviour: Perceived behavioural control or affective attitude? Br J Soc Psychol/Br Psychol Soc. 2005; 44(Pt 3): 479–496.

Deci EL, Ryan RM. Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum; 1985.

Hagger M, Chatzisarantis NLD, eds. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Exercise and Sport. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2007.

Vuchinich RE, Tucker JA. Behavioral theories of choice as a framework for studying drinking behavior. J Abnorm Psychol. 1983; 92: 408–416.

Epstein LH, Roemmich JN. Reducing sedentary behaviour: Role in modifying physical activity. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2001; 29: 103–108.

Wankel LM. The importance of enjoyment to adherence and psychological benefits from physical activity. Int J Sport Psychol. 1993; 24: 151–169.

Manstead ASR, Parker D. Evaluating and extending the theory of planned behaviour. Eur Rev Soc Psychol. 1995; 6: 69–95.

Van der Pligt J, Zeelenberg M, VanDijk WW, de Vries NK, Richard R. Affect, attitudes and decisions: Let’s be more specific. Eur J Soc Psychol. 1998; 8: 33–66.

Zanna MP, Rempel JK. Attitudes: A new look at an old concept. In: Bar-Tal D, Kruglanski AW, eds. The social psychology of knowledge. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1988.

Ekkekakis P. Affect circumplex redux: The discussion on its utility as a measurement framework in exercise psychology continues. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology. 2008; 1: 139–159.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977; 84: 191–215.

Hall PA, Fong GT. Temporal self-regulation theory: A model for individual health behavior. Health Psychology Review. 2007; 1: 6–52.

Rhodes RE, Conner M. Comparison of behavioral belief structures in the physical activity domain. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2009 in press.

Rhodes RE, Blanchard CM, Matheson DH. A multi-component model of the theory of planned behavior. Br J Health Psychol. 2006; 11: 119–137.

Trost SG, Owen N, Bauman A, Sallis JF, Brown W. Correlates of adult's participation in physical activity: Review and update. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002; 34: 1996–2001.

Public Health Agency of Canada (2008) The Healthy Living Unit: The Benefits of Physical Activity.

Rhodes RE, Macdonald H, McKay HA. Predicting physical activity intention and behaviour among children in a longitudinal sample. Soc Sci Med. 2006; 62: 3146–3156.

Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Vol. Version 5.0.1. 2008, The Cochrane Collaboration.

Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998; 52: 377–384.

Grade Working Group. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Br Med J. 2004; 328: 1490.

Hedges LV, Vevea JL. Fixed- and random-effects models in meta-analysis. Psychol Methods. 1998; 3(4): 486–504.

Cohen J, Cohen P. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1983.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 2003; 327(7414): 557–560.

Biostat, Comprehensive Meta-analysis-2. 2006: Englewood, New Jersey.

Nigg CR, Lippke S, Maddock JE. Factorial invariance of the theory of planned behavior applied to physical activity across gender, age, and ethnic groups. Psychology of Sport & Exercise. 2009; 10(2): 219–225.

McArthur LH, Raedeke TD. Race and sex differences in college student physical activity correlates. Am J Health Behav. 2009; 33(1): 80–90.

McIntyre CA, Rhodes RE. Correlates of leisure-time physical activity during transitions to motherhood. Women Health. 2009; 49(1): 66–83.

Bellows-Riecken KH, Rhodes RE, Hoffert KM. Motives for lifestyle and exercise activities: A comparison using the theory of planned behaviour. European Journal of Sport Science. 2008; 8(5): 305–313.

Blanchard CM, Fisher J, Sparling P, et al. Understanding physical activity behavior in African American and Caucasian College Students: An application of the theory of planned behavior. J Am Coll Health. 2008; 56: 341–346.

Blanchard CM, Fisher J, Sparling P, Nehl E, Rhodes RE, Courneya KS, Baker F, Rupp J. Ethnicity and the theory of planned behavior in an exercise context: A mediation and moderation perspective in college students. Psychology of Sport and Exercise. 2008; 9: 527–545.

Calitri R, Lowe R, Eves FF, Bennett P. Associations Between Visual Attention, Implicit and Explicit Attitude and Behaviour for Physical Activity. Routledge; 2008: 1–19.

Cerin E, Vandelanotte C, Leslie E, Merom D. Recreational facilities and leisure-time physical activity: An analysis of moderators and self-efficacy as a mediator. Health Psychology: Official Journal Of The Division Of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2008; 27(2 Suppl): S126–S135.

Craike MJ. Application of self-determination theory to a study of the determinants of regular participation in leisure-time physical activity. World Leisure. 2008: 58–69.

Ingledew DK, Markland D. The role of motives in exercise participation. Psychol Health. 2008; 23(7): 807–828.

Milne HM, Wallman KE, Guilfoyle A, Gordon SE, Courneya KS. Self-determination theory and physical activity among breast cancer survivors. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2008; 30: 23–38.

Peddle CJ, Plotnikoff RC, Wild TC, Au HJ, Courneya KS. Medical, demographic, and psychosocial correlates of exercise in colorectal cancer survivors: an application of self-determination theory. Supportive Care In Cancer: Official Journal Of The Multinational Association Of Supportive Care In Cancer. 2008; 16(1): 9–17.

Rhodes RE, Blanchard CM. Do sedentary motives adversely affect physical activity? Adding cross-behavioural cognitions to the theory of planned behaviour. Psychol Health. 2008; 23: 789–805.

Rhodes RE, Blanchard CM, Blacklock RE. Do physical activity beliefs differ by age and gender? J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2008; 30: 412–423.

Rhodes RE, et al. Evaluating timeframe expectancies in physical activity social cognition: Are short- and long-term motives different? Behav Med. 2008; 34(3): 85–94.

Rhodes RE, Plotnikoff RC, Courneya KS. Predicting the physical activity intention-behaviour profiles of adopters and maintainers using three social cognition models. Annals Behav Med. 2008; 36: 244–252.

Rogers LQ, Courneya KS, Robbins KT, et al. Physical activity correlates and barriers in head and neck cancer patients. Supportive Care In Cancer: Official Journal Of The Multinational Association Of Supportive Care In Cancer. 2008; 16(1): 19–27.

Rogers LQ, McAuley LQ, Courneya KS, Verhulst SJ. Correlates of physical activity self-efficacy among breast cancer survivors. Am J Health Behav. 2008; 32(6): 594–603.

Ball K, Timperio A, Salmon J, Giles-Corti B, Roberts R, Crawford D. Personal, social and environmental determinants of educational inequalities in walking: A multilevel study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007; 61(2): 108–114.

Blanchard CM, Kupperman J, Sparling P, et al. Ethnicity as a moderator of the theory of planned behavior and physical activity in college students. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2007; 78: 531–541.

Conner M, Rodgers W, Murray T. Conscientiousness and the intention–behavior relationship: Predicting exercise behavior. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2007; 29(4): 518–533.

Gretebeck KA, Black DR, Blue CL, Glickman LT, Huston S, Gretebeck RJ. Physical activity and function in older adults: Theory of planned behavior. Am J Health Behav. 2007; 31(2): 203–214.

Jones LW, Guill B, Keir ST, et al. Using the theory of planned behavior to understand the determinants of exercise intention in patients diagnosed with primary brain cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2007; 16(3): 232–240.

Karvinen KH, Courneya KS, Campbell KL, et al. Correlates of exercise motivation and behavior in a population-based sample of endometrial cancer survivors: An application of the theory of planned behavior. The International Journal Of Behavioral Nutrition And Physical Activity. 2007; 4: 21–21.

McDonough MH, Crocker PRE. Testing self-determined motivation as a mediator of the relationship between psychological needs and affective and behavioral outcomes. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2007; 29(5): 645–663.

Raedeke TD. The relationship between enjoyment and affective responses to exercise. J Appl Sport Psychol. 2007; 19(1): 105–115.

Rhodes RE, Blanchard CM, Matheson DH. Motivational antecedent beliefs of endurance, strength, and flexibility activities. Psychol Health Med. 2007; 12: 148–162.

Rhodes RE, et al. Prediction of leisure-time walking: An integration of social cognitive, perceived environmental, and personality factors. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2007; 4: 51.

Scott EJ, Eves FF, French DP, Hopp R. The theory of planned behaviour predicts self-reports of walking, but does not predict step count. Br J Health Psychol. 2007; 12(4): 601–620.

Temple VA. Barriers, enjoyment, and preference for physical activity among adults with intellectual disability. International Journal Of Rehabilitation Research. Internationale Zeitschrift Für Rehabilitationsforschung. Revue Internationale De Recherches De Réadaptation. 2007; 30(4): 281–287.

Bopp M, Wilcox S, Laken M, et al. Factors associated with physical activity among African-American men and women. Am J Prev Med. 2006; 30(4): 340–346.

Brown SG, Rhodes RE. Relationships among dog ownership and leisure time walking amid Western Canadian adults. Am J Prev Med. 2006; 30: 131–136.

Courneya KS, Conner M, Rhodes RE. Effects of different measurement scales on the variability and predictive validity of the “two-component” model of the theory of planned behavior in the exercise domain. Psychol Health. 2006; 21: 557–570.

Daley AJ, Duda JL. Self-determination, stage of readiness to change for exercise, and frequency of physical activity in young people. European Journal of Sport Science. 2006; 6(4): 231–243.

Edmunds J, Ntoumanis N, Duda JL. A test of self-determination theory in the exercise domain. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2006; 36(9): 2240–2265.

Hunt-Shanks TT, Blanchard CM, Baker F, et al. Exercise use as complementary therapy among breast and prostate cancer survivors receiving active treatment: Examination of exercise intention. Integrative Cancer Therapies. 2006; 5(2): 109–116.

Jones LW, Courneya KS, Vallance JK, et al. Understanding the determinants of exercise intentions in multiple myeloma cancer survivors: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Cancer Nurs. 2006; 29(3): 167–175.

Motl RW, Snook EM, McAuley E, Scott JA, Douglass ML. Correlates of physical activity among individuals with multiple sclerosis. Annals Behav Med. 2006; 32(2): 154–161.

McNeill LH, Wyrwich KW, Brownson RC, Clark EM, Kreuter MW. Individual, social environmental, and physical environmental influences on physical activity among black and white adults: A structural equation analysis. Annals Of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication Of The Society Of Behavioral Medicine. 2006; 31(1): 36–44.

Rhodes RE, Blanchard CM. Conceptual categories or operational constructs? Evaluating higher order theory of planned behavior structures in the exercise domain. Behav Med. 2006; 31: 141–150.

Rhodes RE, Blanchard CM, Matheson DH, Coble J. Disentangling motivation, intention, and planning in the physical activity domain. Psychology of Sport and Exercise. 2006; 7: 15–27.

Courneya KS, Vallance JKH, Jones LW, Reiman T. Correlates of exercise intentions in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma survivors: An application of the theory of planned behavior. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2005; 27(3): 335.

Hagger M, Chatzisarantis NLD. First- and higher-order models of attitudes, normative influence, and perceived behavioural control in the theory of planned behaviour. Br J Soc Psychol. 2005; 44: 513–535.

Rhodes RE, Courneya KS, Jones LW. The theory of planned behavior and lower-order personality traits: Interaction effects in the exercise domain. Pers Individ Differ. 2005; 38(2): 251–265.

Rogers LQ, Shah P, Dunnington G, et al. Social cognitive theory and physical activity during breast cancer treatment. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005; 32(4): 807–815.

Sorensen L. Correlates of physical activity among middle-aged Finnish male police officers. Occup Med (Oxford, England). 2005; 55(2): 136–138.

Tsai EH-L. A cross-cultural study of the influence of perceived positive outcomes on participation in regular active recreation: Hong Kong and Australian University students. Leis Sci. 2005; 27(5): 385–404.

Payne N, Jones F, Harris PR. The role of perceived need within the theory of planned behaviour: A comparison of exercise and healthy eating. Br J Health Psychol. 2004; 9(4): 489–504.

Wilson PM, Rodgers WM, Fraser SN, Murray TC. Relationships between exercise regulations and motivational consequences in university students. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2004; 75(1): 81–91.

Eves F, Hoppe R, McLaren L. Prediction of specific types of physical activity using the theory of planned behavior. J Appl Biobehav Res. 2003; 8(2): 77–95.

Rhodes RE, Courneya KS. Modelling the theory of planned behaviour and past behaviour. Psychol Health Med. 2003; 8: 57–69.

Salmon J, Owen N, Crawford D, Bauman A, Sallis JF. Physical activity and sedentary behavior: A population-based study of barriers, enjoyment, and preference. Health Psychol. 2003; 22: 178–188.

Rovniak LS, Anderson ES, Winett RA, Stephen RS. Social cognitive determinants of physical activity in young adults: A prospective structural equation analysis. Annals Of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication Of The Society Of Behavioral Medicine. 2002; 24(2): 149–156.

Booth ML, Owen N, Bauman A, Clavisi O, Leslie E. Social-cognitive and perceived environment influences associated with physical activity in older Australians. Prev Med. 2000; 31(1): 15–22.

Johnson NA, Heller RF. Prediction of patient nonadherence with home-based exercise for cardiac rehabilitation: The role of perceived barriers and perceived benefits. Prev Med. 1998; 27(1): 56–64.

Ryan RM, Frederick CM, Lepes D, Rubio N, Sheldon KM. Intrinsic motivation and exercise adherence./Motivation intrinseque et adhesion a l'exercice physique. Int J Sport Psychol. 1997; 28(4): 335–354.

Frederick CM, Morrison C, Manning T. Motivation to participate, exercise affect, and outcome behaviors toward physical activity. Percept Mot Skills. 1996; 82(2): 691–701.

Ajzen I, Driver BL. Prediction of leisure participation from behavioral, normative, and control beliefs: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Leis Sci. 1991; 13: 185–204.

Sallis JF, Hovell MF, Hofstetter CR, et al. A multivariate study of determinants of vigorous exercise in a community sample. Prev Med. 1989; 18(1): 20–34.

Lustyk MKB, Wildman L, Paschane AAE, Oldon KC. Physical activity and quality of life: Assessing the influence of activity frequency, intensity, volume, and motives. Behav Med (Washington, D.C.). 2004; 30(3): 124–131.

Wilson PM, Rodgers WM, Fraser SN. Examining the psychometric properties of the behavioral regulation in exercise questionnaire. Meas Phys Educ Exerc Sci. 2002; 6(1): 1–21.

Frederick CM, Ryan RM. Differences in motivation for sport and exercise and their relations with participation and mental health. J Sport Behav. 1993; 16(3): 124–146.

Oman R, McAuley E. Intrinsic motivation and exercise behavior. J Health Educ. 1993; 24(4): 232–238.

Stevinson C, Tonkin K, Capstick V, et al. A population-based study of the determinants of physical activity in ovarian cancer survivors. Journal Of Physical Activity & Health. 2009; 6(3): 339–346.

Karvinen KH, Courneya KS, Plotnikoff RC, Spence JC, Venner PM, North S. A prospective study of the determinants of exercise in bladder cancer survivors using the Theory of Planned Behavior. Supportive Care In Cancer: Official Journal Of The Multinational Association Of Supportive Care In Cancer. 2009; 17(2): 171–179.

Gardner RE, Hausenblas HA. Exercise and diet determinants of overweight women participating in an exercise and diet program: A prospective examination of the theory of planned behavior. Women Health. 2005; 42(4): 37–62.

Brown SA. Measuring perceived benefits and perceived barriers for physical activity. Am J Health Behav. 2005; 29(2): 107–116.

Sørensen M. Motivation for physical activity of psychiatric patients when physical activity was offered as part of treatment. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2006; 16(6): 391–398.

Segar M, Spruijt-Metz D, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Go figure? Body-shape motives are associated with decreased physical activity participation among midlife women. Sex Roles. 2006; 54(3): 175–187.

Standage M, Sebire SJ, Loney T. Does exercise motivation predict engagement in objectively assessed bouts of moderate-intensity exercise?: A self-determination theory perspective. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2008; 30(4): 337–352.

Hoyt AL, Rhodes RE, Hausenblas HA, Giacobbi PR. Integrating five-factor model facet-level traits with the theory of planned behavior and exercise. Psychology of Sport & Exercise. 2009; 10(5): 565–572.

Dyrlund AK, Wininger SR. The effects of music preference and exercise intensity on psychological variables. J Music Ther. 2008; 45(2): 114–134.

Kliman A, Rhodes RE. Do government brochures affect physical activity cognition? A pilot study of Canada’s Physical Activity Guide to Healthy Active Living. Psychol Health Med. 2008; 13: 415–422.

Milne HM, Wallman KE, Gordon S, Courneya KS. Impact of a combined resistance and aerobic exercise program on motivational variables in breast cancer survivors: A randomized trial. Annals Behav Med. 2008; 36: 158–166.

Parrott MW, Tennant LK, Olejnik S, Poudevigne MS. Theory of planned behavior: Implications for an email-based physical activity intervention. Psychology of Sport and Exercise. 2008; 9: 511–526.

Vallance JK, Courneya KS, Plotnikoff RC, Mackey JR. Analyzing theoretical mechanisms of physical activity behavior change in breast cancer survivors: Results from the activity promotion (ACTION) trial. Annals Of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication Of The Society Of Behavioral Medicine. 2008; 35(2): 150–158.

Hu L, Motl RW, McAuley E, Konopack JF. Effects of self-efficacy on physical activity enjoyment in college-aged women. Int J Behav Med. 2007; 14: 92–96.

Plante TG, Gores C, Brecht C, Carrow J, Imbs A, Willemsen E. Does exercise environment enhance the psychological benefits of exercise for women? Int J Stress Manag. 2007; 14: 88–98.

Martin Ginis KA, Jung ME, Brawley LR, et al. The effects of physical activity enjoyment on sedentary older adults' physical activity attitudes and intentions. J Appl Biobehav Res. 2006; 11(1): 29–43.

Plante TG, Cage C, Clements S, Stover A. Psychological benefits of exercise paired with virtual reality: Outdoor exercise energizes whereas indoor virtual exercise relaxes. Int J Stress Manag. 2006; 13(1): 108–117.

Rovniak LS, Hovell MF, Wojcik JR, Winett RA, Martinez-Donate AP. Enhancing theoretical fidelity: An e-mail-based walking program demonstration. Am J Health Promot. 2005; 20: 85–95.

Levy SS, Cardinal BJ. Effects of a self-determination theory-based mail-mediated intervention on adults' exercise behavior. Am J Health Promot. 2004; 18: 345–349.

Nichols JF, Wellman E, Caparosa S, Sallis JF, Calfas KJ, Rowe R. Impact of a worksite behavioral skills intervention. Am J Health Promot. 2000; 14: 218–221.

Patten CA, Armstrong CA, Martin JE, Sallis JF, Booth J. Behavioral control of exercise in adults: Studies 7 and 8. Psychol Health. 2000; 15(4): 571.

Castro CM, Sallis JF, Hickman SA, Lee RE, Chen AH. A prospective study of psychosocial correlates of physical activity for ethnic minority women. Psychol Health. 1999; 14(2): 277.

Sallis JF, Calfas KJ, Alcaraz JE, Gehrman C, Johnson BS. Potential mediators of change in a physical activity promotion course for university students: Project Grad. Annals Behav Med. 1999; 21: 149–158.

Dwyer JJM. Effect of perceived choice of music on exercise intrinsic motivation. Health Values: The Journal of Health Behavior Education & Promotion. 1995; 19(2): 18–26.

Hardeman W, Kinmonth AL, Michie S, Sutton S. Impact of a physical activity intervention program on cognitive predictors of behaviour among adults at risk of Type 2 diabetes (ProActive randomised controlled trial). International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2009; 6: 10.

Ajzen I. Constructing a TPB questionnaire: Conceptual and methodological considerations. 2002 [cited 2007 April 7]; Available from: http://www-unix.oit.umass.edu/~aizen/.

Jones LW, Sinclair RC, Rhodes RE, Courneya KS. Promoting exercise behaviour: An integration of persuasion theories and the theory of planned behaviour. Br J Health Psychol. 2004; 9: 505–521.

Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992; 112: 155–159.

Spence JC, Burgess JA, Cutumisu N, et al. Self-efficacy and physical activity: A quantitative review. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2006; 28: S172.

Hagger M, Chatzisarantis NLD, Biddle SJH. A meta-analytic review of the theories of reasoned action and planned behavior in physical activity: Predictive validity and the contribution of additional variables. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2002; 24: 1–12.

Sutton S. Predicting and explaining intentions and behavior: How are we doing? J Appl Soc Psychol. 1998; 28: 1317–1338.

Bellows-Riecken KH, Rhodes RE. The birth of inactivity? A review of physical activity and parenthood. Prev Med. 2008; 46: 99–110.

Rhodes RE, Smith NEI. Personality correlates of physical activity: A review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2006; 40: 958–965.

Lawton R, Conner M, Parker D. Beyond cognition: Predicting health risk behaviors from instrumental and affective beliefs. Health Psychol. 2007; 26: 259–267.

Loewenstein GF, Weber E, Hsee CK, Welch N. Risk as feelings. Psychol Bull. 2001; 127: 267–286.

Giner-Sorolla R. Guilty pleasures and grim necessities: Affective attitudes in dilemmas of self-control. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001; 80: 206–221.

Ekkekakis P, Hall EE, Petruzzello SJ. The relationship between exercise intensity and affective responses demystified: To crack the 40 year-old nut, replace the 40-year-old nutcracker! Annals Behav Med. 2008; 35: 136–149.

Sandberg T, Conner M. Anticipated regret as an additional predictor in the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis. Br J Soc Psychol. 2008; 47: 589–606.

Rhodes RE, Courneya KS. Self-efficacy, controllability, and intention in the theory of planned behavior: Measurement redundancy or causal independence? Psychol Health. 2003; 18: 79–91.

Rhodes RE, Blanchard CM. What do confidence items measure in the physical activity domain? J Appl Soc Psychol. 2007; 37: 753–768.

Rhodes RE, Courneya KS. Differentiating motivation and control in the theory of planned behavior. Psychol Health Med. 2004; 9: 205–215.

Ekkekakis P, Lind E. Exercise does not feel the same when you are overweight: The impact of self-selected and imposed intensity on affect and exertion. Int J Obes. 2006; 30: 652–660.

McAuley E, Talbot HM, Martinez S. Manipulating self-efficacy in the exercise environment in women: Influences on affective responses. Health Psychol. 1999; 18: 288–294.

Motl RW, Berger BG, Leuschen PS. The role of enjoyment in the exercise-mood relationship. Int J Sport Psychol. 2000; 31: 347–363.

Csikszentmihalyi M. Flow, the psychology of experience. New York: Harper & Row; 1990.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix A

Studies of affective expectancies and physical activity, excluded studies (k = 61) (DOC 41 kb)

Appendix B

Search syntax (DOC 28 kb)

Appendix C

Data extraction, studies of affective expectations and physical activity (DOC 183 kb)

Appendix D

Quality of correlational and experimental studies (DOC 184 kb)

About this article

Cite this article

Rhodes, R.E., Fiala, B. & Conner, M. A Review and Meta-Analysis of Affective Judgments and Physical Activity in Adult Populations. ann. behav. med. 38, 180–204 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-009-9147-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-009-9147-y