Abstract

Background

Little is known about whether educational gradients in smoking patterns can be explained by financial measures of socioeconomic status (SES) and/or personality traits.

Purpose

To assess whether the relationship of education to (1) never smoking and (2) having quit smoking would be confounded by financial measures of SES or by personality; whether lower Neuroticism and higher Conscientiousness would be associated with having abstained from or quit smoking; and whether education effects were modified by personality.

Method

Using data from the Midlife Development in the US National Survey, 2,429 individuals were classified as current (n = 695), former (n = 999), or never (n = 735) smokers. Multinomial logistic regressions examined study questions.

Results

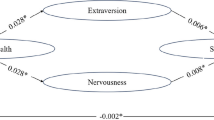

Greater education was strongly associated with both never and former smoking, with no confounding by financial status and personality. Never smoking was associated with lower Openness and higher Conscientiousness, while have quit was associated with higher Neuroticism. Education interacted additively with Conscientiousness to increase and with Openness to decrease the probability of never smoking.

Conclusions

Education and personality should be considered unconfounded smoking risks in epidemiologic and clinical studies. Educational associations with smoking may vary by personality dispositions, and prevention and intervention programs should consider both sets of factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

World Health Organization. The world health report 2002: Reducing risks, promoting healthy life. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002.

Federico B, Costa G, Kunst AE. Educational inequalities in initiation, cessation, and prevalence of smoking among 3 Italian birth cohorts. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(5):838-845.

Cavelaars AEJM, Kunst AE, Geurts JJM, et al. Educational differences in smoking: International comparison. Br Med J. 2000;320(7242):1102-7.

Pierce JP, Fiore MC, Novotny TE, et al. Trends in cigarette-smoking in the United States—educational differences are increasing. JAMA. 1989;261(1):56-60.

Droomers ML, Schrijvers CTM, Mackenbach JP. Why do lower educated people continue smoking? Explanations from the longitudinal GLOBE study. Health Psychol. 2002;21(3):263-272.

Fernandez E, Schiaffino A, Garcia M, et al. Widening social inequalities in smoking cessation in Spain, 1987–1997. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001;55(10):729-30.

Galobardes B, Smith GD, Lynch JW. Systematic review of the influence of childhood socioeconomic circumstances on risk for cardiovascular disease in adulthood. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16(2):91-104.

Galobardes B, Shaw M, Lawlor DA, et al. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 2). J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(2):95-101.

Goldberg LR. The structure of phenotypic personality traits. Am Psychol. 1993;48(1):26-34.

McCrae RR, Costa PT Jr. Personality trait structure as a human universal. Am Psychol. 1997;52:509-16.

Terracciano A, Costa PT. Smoking and the five-factor model of personality. Addiction. 2004;99(4):472-81.

Gilbert DG, Gilbert BO. Personality, psychopathology, and nicotine response as mediators of the genetics of smoking. Behav Genet. 1995;25(2):133-47.

Malouff JM, Thorsteinsson EB, Schutte NS. The five-factor model of personality and smoking: A meta-analysis. J Drug Ed. 2006;36(1):47-58.

Munafo MR, Zetteler JI, Clark TG. Personality and smoking status: A meta-analysis. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(3):405-13.

Hooten WM, Wolter TD, Ames SC, et al. Personality correlates related to tobacco abstinence following treatment. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2005;35(1):59-74.

Costa PT, McCrae RR. Stress, smoking motives, and psychological well-being: The illusory benefits of smoking. Adv Behav Res Ther. 1981;3:125-50.

Institute of Medicine. Genes, behavior, and the social environment: Moving beyond the nature/nurture debate. In: Hernandez LM, Blazer DG, eds. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2006

Black DS, Townsend P, Davidson N. Inequalities in health: The black report. Harmondsworth: Penguin; 1988.

Blane D, Bartley M, Davey Smith G. Making sense of socio-economic health inequalities. In: Field DTS, ed. Sociological perspectives on health, illness, and health care. Bodmin, Cornwall: Blackwell Science; 1998:79-96.

Conger RD, Donnellan MB. An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:175-99.

John OP, Caspi A, Robins RW, et al. The little 5—exploring the nomological network of the 5-factor model of personality in adolescent boys. Child Dev. 1994;65(1):160-78.

Borghans L, Duckworth AL, Heckman JJ, ter Weel B. The economics and psychology of personality traits. NBER;Working Paper No. 13810

Kohn ML, Schooler C. Occupational experience and psychological functioning: An assessment of reciprocal effects. Am Sociol Rev. 1973;38(1):97-118.

Kohn ML, Schooler C. The reciprocal effects of the substantive complexity of work and intellectual flexibility: A longitudinal assessment. Am J Soc. 1978;84(1):24-52.

Kohn ML, Schooler C. Job conditions and personality: A longitudinal assessment of their reciprocal effects. Am J Soc. 1982;87(6):1257-86.

Elovainio M, Kivimaki M, Kortteinen M, et al. Socioeconomic status, hostility and health. Pers Individ Dif. 2001;31(3):303-15.

Kivimaki M, Elovainio M, Kokko K, et al. Hostility, unemployment and health status: Testing three theoretical models. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(10):2139-52.

Adler N, Matthews K. Health psychology: Why do some people get sick and some stay well? Annu Rev Psychol. 1994;45:229-259.

Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kessler RC. The MIDUS National Survey: An overview. In: Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kesller RC, eds. How healthy are we? A national study of well being at midlife. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2004:1-34.

Lachman ME, Weaver SL (1997) The Midlife Development Inventory (MIDI) personality scales: Scale construction and scoring. Brandeis University Psychology Department MS 062

Goldberg LR. The development of markers for the big-five factor structure. Psychol Assess. 1992;4(1):26-42.

Mickey R, Greenland S. The impact of confounder selection criteria on effect estimation. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:125-37.

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate—a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Series B Methodol. 1995;57(1):289-300.

Knol MJ, van der Tweel I, Grobbee DE, Numans ME, Geerlings M. Estimating interaction on an additive scale between continuous determinants in a logistic regression model. Int J Epi. 2007;36:1111-8.

Rothman KJ. Epidemiology: An introduction. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002.

Bruine de Bruin W, Parker AM, Fischhoff B. Individual differences in adult decision-making competence. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;92(5):938-956.

Kuh D, Ben-Shlomo Y, Lynch J, et al. Life course epidemiology. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(10):778-83.

Grimard F, Parent D. Education and smoking: Were Vietnam war draft avoiders more likely to avoid smoking? J Health Econ. 2007;26:896-926.

de Walque D. Does education affect smoking behaviors? Evidence using the Vietnam draft as an instrument for college education. J Health Econ. 2006;26:877-895.

Bogg T, Roberts BW. Conscientiousness and health-related behaviors: A meta-analysis of the leading behavioral contributors to mortality. Psychol Bull. 2004;130(6):887-919.

Soane E, Chmiel N. Are risk preferences consistent? The influence of decision domain and personality. Pers Individ Dif. 2005;38(8):1781-91.

Hampson SE, Andrews JA, Barckley M, et al. Conscientiousness, perceived risk, and risk-reduction behaviors: A preliminary study. Health Psychol. 2000;19(5):496-500.

Hampson SE, Andrews JA, Barckley M, et al. Personality traits, perceived risk, and risk-reduction behaviors: A further study of smoking and radon. Health Psychol. 2006;25(4):530-536.

McCrae RR. Openness to experience: Expanding the boundaries of factor V. Eur J Pers. 1994;8(4):251-72.

Flory K, Lynam D, Milich R, et al. The relations among personality, symptoms of alcohol and marijuana abuse, and symptoms of comorbid psychopathology: Results from a community sample. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;10(4):425-34.

Friedman HS. Long-term relations of personality and health: Dynamisms, mechanisms, tropisms. J Pers. 2000;68(6):1089-107.

Magnan RE, Koblitz AR, Zielke DJ, McCaul KD. The effects of warning smokers on perceived risk, worry, and motivation to quit. Ann Beh Med. 2009;37:46-57.

Nettle D. The evolution of personality variation in humans and other animals. Am Psychol. 2006;61(6):622-631.

Weinstein ND. Perceived probability, perceived severity, and health-protective behavior. Health Psychol. 2000;19(1):65-74.

Wikler D. Personal and social responsibility for health. Ethics Int Aff. 2002;16(2):47-55.

Wikler D. Who should be blamed for being sick? Health Ed Q. 1987;14(1):11-25.

Minkler M. Personal responsibility for health? A review of the arguments and the evidence at century’s end. Health Educ Behav. 1999;26(1):121-40.

Cappelen AW, Norheim OF. Responsibility in health care: A liberal egalitarian approach. J Med Ethics. 2005;31(8):476-80.

MacKinnon DP, Krull JL, Lockwood CM. Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prev Sci. 2000;1:173-81.

Gallacher JEJ. Methods of assessing personality for epidemiologic-study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1992;46(5):465-9.

Krall EA, Valadian I, Dwyer JT, et al. Accuracy of recalled smoking data. Am J Public Health. 1989;79(2):200-2.

Suadicani P, Hein HO, Gyntelberg F. Serum validated tobacco use and social inequalities in risk of ischemic-heart-disease. Int J Epidemiol. 1994;23(2):293-300.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank two anonymous reviewers for their comments on earlier versions of this paper.

Competing Interests

None

Support

Preparation of this manuscript was supported by United States Public Health Grant T32 MH073452, to Jeffrey Lyness and Paul Duberstein, and K08AG031328 to Ben Chapman.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Chapman, B., Fiscella, K., Duberstein, P. et al. Education and Smoking: Confounding or Effect Modification by Phenotypic Personality Traits?. ann. behav. med. 38, 237–248 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-009-9142-3

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-009-9142-3