Abstract

Background

Emergency departments (EDs) have strong potential to initiate tobacco interventions with economically disadvantaged populations.

Purpose

We piloted three ED-initiated tobacco interventions and derived parameter estimates for future trials.

Methods

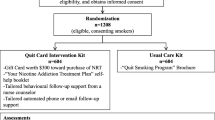

The study enrolled adult patients being treated in an urban ED who were daily smokers. Exclusion criteria included severe illness or pain, isolation (for contagion), altered mental status, an insurmountable language barrier, temporary residence, and lack of telephone access. Subjects in the Bedside + Booster group received motivational counseling by a trained counselor at the bedside, up to three telephone sessions post-visit, and a self-help guide. Subjects in the Faxed Referral group had their personal contact information faxed to the hospital’s tobacco dependence clinic, whereupon they received identical treatment as the Bedside + Booster group, but all sessions occurred over the telephone (i.e., no bedside counseling). The Standard Referral group received the self-help guide and a referral to the hospital’s tobacco dependence clinic. We used a 2:2:1 randomization schedule to maximize our experience with the motivational interventions. Outcomes were assessed at 1 and 3 months.

Results

We enrolled 90 subjects. Of the 36 subjects assigned to the Bedside + Booster condition, 31 (87%) completed bedside counseling and at least one booster session, while 22 (61%) completed the maximum four sessions. Of the 37 subjects assigned to the Faxed Referral group, 28 (76%) completed at least one telephone session, while 19 (51%) completed the maximum four sessions. Quit attempts over the 3 months ranged from 18% (Standard Referral) to 57% (Faxed Referral). Seven-day abstinence was attained by 8% (Bedside + Booster), 14% (Faxed Referral), and 6% (Standard Referral) at 3 months.

Conclusions

Motivational cessation counseling can be feasibly initiated during the ED encounter with minimal medical staff involvement. Adequately powered trials are needed to study ED-initiated interventions that include post-visit follow-up.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

McCaig LF, Burt CW. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2002 emergency department summary. Adv Data. 2004; 340: 1–34.

Bernstein SL, Boudreaux ED, Cydulka RK, et al. Tobacco control interventions in the emergency department: A joint statement of emergency medicine organizations. Ann Emerg Med. 2006; 4: 417–426. (also published in J Emerg Nursing. 2006; 32: 370–381).

Boudreaux ED, Hunter GC, Bos K, Clark S, Camargo CA Jr. Predicting smoking stage of change among emergency department patients and visitors. Acad Emerg Med. 2006; 13: 39–47.

Boudreaux ED, Kim S, Hohrmann JL, Clark S, Camargo CA Jr. Interest in smoking cessation among emergency department patients. Health Psychol. 2005; 24: 220–224.

Lowenstein SR, Koziol-McLain J, Thompson M, et al. Behavioral risk factors in emergency department patients: A multisite survey. Acad Emerg Med. 1998; 5: 781–787.

Prochazka A, Koziol-McLain J, Tomlinson D, Lowenstein SR. Smoking cessation counseling by emergency physicians: Opinions, knowledge, and training needs. Acad Emerg Med. 1995; 2: 211–216.

Williams JM, Chinnis AC, Gutman D. Health promotion practices of emergency physicians. Am J Emerg Med. 2000; 18: 17–21.

Wood K, Thompson E, Baumann BM, Boudreaux ED. Emergency physicians’ opinions and practices regarding screening and interventions for patients who use substances. Presented at the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy, November, 2003.

Longabaugh R, Woolard RE, Nirenberg TD, et al. Evaluating the effects of a brief motivational intervention for injured drinkers in the emergency department. J Stud Alcohol. 2001; 62: 806–816.

Bernstein E, Bernstein J, Levenson S. Project ASSERT: An ED-based intervention to increase access to primary care, preventive services, and the substance abuse treatment system. Ann Emerg Med. 1997; 30: 181–189.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Screening: Adds prevention to treatment. Available from: http://www.samhsa.gov/SAMHSA_News/VolumeXIV_1/index2.htm and http://sbirt.samhsa.gov/about.htm. Accessed September 15, 2006.

National Institute on Drug Abuse: Program Announcement PA-03-126: Behavioral Therapy Development Program. Available from: http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/PA-03-126.html. Accessed October 6, 2006

Ashenden R, Silagy C, Weller D. A systematic review of the effectiveness of promoting lifestyle change in general practice. Fam Pract. 1997; 14: 160–176.

Law M, Tang JL. An analysis of the effectiveness of interventions intended to help people stop smoking. Arch Int Med. 1995; 155: 1933–1941.

Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change Addictive Behavior. New York: Guilford; 2002.

Rollnick S, Allison J, Ballasiotes S, et al. Variations on a theme: Motivational interviewing and its adaptations. In: Miller WR, Rollnick S, eds. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change Addictive Behavior. New York: Guilford; 2002.

Bernstein SL, Becker BM. Preventive care in the emergency department: Diagnosis and management of smoking and smoking-related illness in the emergency department: A systematic review. Acad Emerg Med. 2002; 9: 720–729.

Richman PB, Dinowitz S, Nashed AH, et al. The emergency department as a potential site for smoking cessation intervention: A randomized, controlled trial. Acad Emerg Med. 2000; 7: 348–353.

WiredMD. Available from: http://www.wired.md/. Accessed September 6, 2006.

Hughes JR, Keely JP, Niaura RS, et al. Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: Issues and recommendations. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003; 5: 13–25.

Hughes JR, Keely J, Naud S. Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated smokers. Addiction. 2004; 99: 29–38.

Kozlowski LT, Porter CQ, Orleans CT, Pope MA, Heatherton T. Predicting smoking cessation with self-reported measures of nicotine dependence: FTQ, FTND, and HSI. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1994; 34: 211–216.

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983; 51: 390–395.

Rollnick S, Butler CC, Stott N. Helping smokers make decisions: The enhancement of brief intervention for general medical practice. Patient Ed Counsel. 1997; 31: 191–203.

Cherpitel C. Brief screening instruments for alcoholism. Alcohol Health Res World. 1997; 21: 348–351.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The patient health questionnaire-2: Validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003; 41: 1284–1292.

Bock B, Becker B, Partridge R, Niaura R. Smoking cessation among patients in the chest pain observation unit. Ann Behav Med. 2005; 61: 29S.

Colby S, Monti P, O’Leary-Tevyaw T, et al. Brief motivational intervention for adolescent smokers in medical settings. Addict Behav. 2005; 30: 865–874.

Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Available from: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/apps/media/press/release.asp?Counter=1395. Accessed October 6, 2006.

Prochaska JO, Velicer WF, Fava JL, Rossi JS, Tsoh JY. Evaluating a population-based recruitment approach and a stage-based expert system intervention for smoking cessation. Addict Behav. 2001; 26: 583–602.

Cummings SR, Rubin SM, Oster G. The cost-effectiveness of counseling smokers to quit. JAMA. 1989; 261: 75–79.

Abrams DB, Borrelli B, Shadel WG, et al. Adherence to treatment for nicotine dependence. In: Shumaker SA, Schron EB, Ockene J, eds. The Handbook of Health Behavior Change. 2nd ed. New York: Springer; 1998: 137–165.

Mordan E, Weeks A, Geffrard M, et al. Expired carbon monoxide validation of self-reported smoking among ED patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2005; 12S: 45.

Boudreaux E, Ary R, St John B, Mandry CV. Telephone contact of low socioeconomic status patients visiting an emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2000; 18: 409–415.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Funding Support: This study was supported by a NIH/NIDA K23 Research Career Award (EDB) grant (DA-16698-01).

About this article

Cite this article

Boudreaux, E.D., Baumann, B.M., Perry, J. et al. Emergency Department Initiated Treatments for Tobacco (EDITT): A Pilot Study. ann. behav. med. 36, 314–325 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-008-9066-3

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-008-9066-3