Abstract

Background

Tailored health communications to date have been based on a rather narrow set of theoretical constructs.

Purpose

This study was designed to test whether tailoring a print-based fruit and vegetable (F & V) intervention on relatively novel constructs from self-determination theory (SDT) and motivational interviewing (MI) increases intervention impact, perceived relevance, and program satisfaction. The study also aimed to explore possible user characteristics that may moderate intervention response.

Methods

African American adults were recruited from two integrated health care delivery systems, one based in the Detroit Metro area and the other in the Atlanta Metro area, and then randomized to receive three tailored newsletters over 3 months. One set of newsletters was tailored only on demographic and social cognitive variables (control condition), whereas the other (experimental condition) was tailored on SDT and MI principles and strategies. The primary focus of the newsletters and the primary outcome for the study was fruit and vegetable intake assessed with two brief self-report measures. Preference for autonomy support was assessed at baseline with a single item: “In general, when it comes to my health I would rather an expert just tell me what I should do”. Most between-group differences were examined using change scores.

Results

A total of 512 (31%) eligible participants, of 1,650 invited, were enrolled, of which 423 provided complete 3-month follow-up data. Considering the entire sample, there were no significant between-group differences in daily F & V intake at 3 month follow-up. Both groups showed similar increases of around one serving per day of F & V on the short form and half a serving per day on the long form. There were, however, significant interactions of intervention group with preference for autonomy-supportive communication as well as with age. Specifically, individuals in the experimental intervention who, at baseline, preferred an autonomy-supportive style of communication increased their F & V intake by 1.07 servings compared to 0.43 servings among controls. Among younger controls, there was a larger change in F & V intake, 0.59 servings, than their experimental group counterparts, 0.29 servings. Conversely, older experimental group participants showed a larger change in F & V, 1.09 servings, than older controls, 0.48.

Conclusion

Our study confirms the importance of assessing individual differences as potential moderators of tailored health interventions. For those who prefer an autonomy-supportive style of communication, tailoring on values and other motivational constructs can enhance message impact and perceived relevance.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Campbell MK, Bernhardt JM, Waldmiller M, et al. Varying the message source in computer-tailored nutrition education. Patient Educ Couns. 1999; 36: 157–169.

Campbell MK, DeVellis BM, Strecher VJ, et al. Improving dietary behavior: The effectiveness of tailored messages in primary care settings. Am J Public Health. 1994; 845: 783–787.

Rimer BK, Orleans CT, Cristinzio S, et al. Does tailoring matter? The impact of a tailored guide on ratings and short-term smoking related outcomes for older smokers. Health Educ Res. 1994; 9: 69–84.

Strecher VJ, Kreuter M, Den Boer DJ, et al. The effects of computer-tailored smoking cessation messages in family practice settings. J Fam Pract. 1994; 393: 262–270.

Kreuter MW, Strecher VJ. Do tailored behavior change messages enhance the effectiveness of health risk appraisal? Results from a randomized trial. Health Educ Res. 1996; 111: 97–105.

Brug J, Glanz K, Van Assema P, et al. The impact of computer-tailored feedback and iterative feedback on fat, fruit, and vegetable intake. Health Educ Behav. 1998; 254: 517–531.

Dijkstra A, De Vries H, Roijackers J. Long-term effectiveness of computer-generated tailored feedback in smoking cessation. Health Educ Res. 1998; 132: 207–214.

Brug J, Steenhuis I, van Assema P, et al. Computer-tailored nutrition education: Differences between two interventions. Health Educ Res. 1999; 142: 249–256.

de Vries H, Brug J. Computer-tailored interventions motivating people to adopt health promoting behaviours: Introduction to a new approach. Patient Educ Couns. 1999; 362: 99–105.

Lipkus IM, Lyna PR, Rimer BK. Using tailored interventions to enhance smoking cessation among African-Americans at a community health center. Nicotine Tob Res. 1999; 11: 77–85.

Strecher VJ. Computer-tailored smoking cessation materials: A review and discussion. Patient Educ Couns. 1999; 36: 107–117.

Campbell MK, Motsinger BM, Ingram A, et al. The North Carolina Black Churches United for Better Health Project: Intervention and process evaluation. Health Educ Behav. 2000; 272: 241–253.

Bernhardt J. Tailoring messages and design in a Web-based skin cancer prevention intervention. Int Electron J Health Educ. 2001; 4: 290–297.

Kreuter MW, Sugg-Skinner C, Holt CL, et al. Cultural tailoring for mammography and fruit and vegetable intake among low-income African-American women in urban public health centers. Prev Med. 2005; 411: 53–62.

Brug J, Oenema A, Campbell MK. Past, present, and future of computer-tailored nutrition education. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003; 774 Suppl: 1028S–1034S.

Kroeze W, Werkman A, Brug J. A systematic review of randomized trials on the effectiveness of computer-tailored education on physical activity and dietary behaviors. Ann Behav Med. 2006; 313: 205–223.

Marcus BH, Napolitano MA, King AC, et al. Telephone versus print delivery of an individualized motivationally tailored physical activity intervention: Project STRIDE. Health Psychol. 2007; 264: 401–409.

Kreuter MW, Strecher VJ, Glassman B. One size does not fit all: the case for tailoring print materials. Ann Behav Med. 1999; 214: 276–283.

Kreuter MW, Wray RJ. Tailored and targeted health communication: Strategies for enhancing information relevance. Am J Health Behav. 2003; 27 Suppl 3: S227–S232.

Brug J, Campbell M, van Assema P. The application and impact of computer-generated personalized nutrition education: A review of the literature. Patient Educ Couns. 1999; 36: 145–156.

Smeets T, Kremers SPJ, de Vries H, Brug J. Effects of tailored feedback on multiple health behaviors. Ann Behav Med. 2007; 332: 117–123.

Oenema A, Tan F, Brug J. Short-term efficacy of a web-based computer tailored nutrition intervention: Main effects and mediators. Ann Behav Med. 2005; 291: 54–63.

Haerens L, Deforche B, Maes L, et al. Evaluation of a 2-year physical activity and healthy eating intervention in middle school children. Health Educ Res. 2006; 216: 911–921.

Strolla LO, Gans KM, Risica PM. Using qualitative and quantitative formative research to develop tailored nutrition intervention materials for a diverse low-income audience. Health Educ Res. 2005; 214: 465–476.

Dijkstra A, De Vries H, Roijackers J. Targeting smokers with low readiness to change with tailored and nontailored self-help materials. Prev Med. 1999; 282: 203–211.

Rakowski W, Ehrich B, Goldstein MG, et al. Increasing mammography among women aged 40–74 by use of a stage-matched, tailored intervention. Prev Med. 1998; 275 Pt 1: 748–756.

Ershoff DH, Quinn VP, Boyd NR, et al. The Kaiser Permanente Prenatal Smoking Cessation Trial: When more isn’t better, what is enough? Am J Prev Med. 1999; 173: 161–168.

Brug J, van Assema P. Differences in use and impact of computer-tailored dietary fat-feedback according to stage of change and education. Appetite. 2000; 343: 285–293.

van Sluijs EM, van Poppel MN, Twisk JW, et al. Effect of a tailored physical activity intervention delivered in general practice settings: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health. 2005; 9510: 1825–1831.

Noar SM, Benac CN, Harris MS. Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychol Bull. 2007; 1334: 673–693.

Shegog R, McAlister AL, Hu S, Ford KC, Meshack AF, Peters RJ. Use of interactive health communication to affect smoking intentions in middle school students: a pilot test of the “Headbutt” risk assessment program. Am J Health Promot. 2005; 195: 334–338.

Williams GC, Rodin GC, Ryan RM, et al. Autonomous regulation and long-term medication adherence in adult outpatients. Health Psychol. 1998; 173: 269–276.

Williams GC, Gagne M, Ryan RM, Deci EL. Facilitating autonomous motivation for smoking cessation. Health Psychol. 2002; 211: 40–50.

Markland D, Ryan RM, Tobin VJ, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing and self-determination theory. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2005; 246: 811–831.

Deci E, Ryan R. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. New York: Plenum; 1985.

Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000; 551: 68–78.

Williams GC, Freedman ZR, Deci EL. Supporting autonomy to motivate patients with diabetes for glucose control. Diabetes Care. 1998; 2110: 1644–1651.

National Center for Health Statistics, Health, United States, 2006 With Chartbook on Trends in the Health of Americans. Hyattsville, Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics; 2006.

Serdula MK, Gillespie C, Kettel-Khan L, et al. Trends in fruit and vegetable consumption among adults in the United States: Behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 1994–2000. Am J Public Health. 2004; 946: 1014–1018.

Kant A, Graubard B, Kumanyika S. Trends in black–white differentials in dietary intakes of U.S. adults, 1971–2002. Am J Prev Med. 2007; 324: 264–272.

Resnicow K, DiIorio C, Soet JE, et al. Motivational interviewing in health promotion: It sounds like something is changing. Health Psychol. 2002; 215: 444–451.

Resnicow K, Davis R, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing for pediatric obesity: Conceptual issues and evidence review. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006; 10612: 2024–2033.

Williams GC, Deci EL. Activating patients for smoking cessation through physician autonomy support. Med Care. 2001; 398: 813–823.

Cacioppo JT, Petty RE, Feinstein JA, Jarvis WBG. Dispositional differences in cognitive motivation: The life and times of individuals varying in need for cognition. Psychol Bull. 1996; 1192: 197–253.

Deci E, Ryan R. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol Inq. 2000; 11: 227–268.

Fuemmeler BF, Masse LC, Yaroch AL, et al. Psychosocial mediation of fruit and vegetable consumption in the Body and Soul Effectiveness Trial. Health Psychol. 2006; 254: 474–483.

Thompson FE, Subar AF, Smith AF, et al. Fruit and vegetable assessment: performance of 2 new short instruments and a food frequency questionnaire. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002; 10212: 1764–1772.

Resnicow K, Odom E, Wang T, et al. Validation of three food frequency questionnaires and twenty four hour recalls with serum carotenoids in a sample of African American adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2000; 152: 1072–1080.

Resnicow K, Coleman-Wallace D, Jackson A, et al. Dietary Change through Black Churches: Baseline results and program description of the eat for life trial. J Cancer Educ. 2000; 15: 156–163.

Resnicow K, Jackson A, Braithwaite R, et al. Healthy body/healthy spirit: Design and evaluation of a church-based nutrition and physical activity intervention using motivational interviewing. Health Educ Res. 2002; 172: 562–573.

Resnicow K, Campbell MK, Carr C, et al. Body and soul. A dietary intervention conducted through African-American churches. Am J Prev Med. 2004; 272: 97–105.

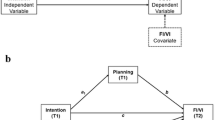

Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986; 516: 1173–1182.

Resnicow K, Jackson A, Blissett D, et al. Results of the healthy body healthy spirit trial. Health Psychol. 2005; 244: 339–348.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Resnicow, K., Davis, R.E., Zhang, G. et al. Tailoring a Fruit and Vegetable Intervention on Novel Motivational Constructs: Results of a Randomized Study. ann. behav. med. 35, 159–169 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-008-9028-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-008-9028-9