Abstract

Both public stigma and perceived self-stigma are prevalent during pandemics threatening a divide among the global community. This systematic review examined the cultural factors associated with viral respiratory-related pandemic stigma. Following PRISMA guidelines, the keywords, “culture, stigma, and pandemic” were searched across relevant databases for empirical papers between January 2000 to March 2022. Quality assessment and coding were adopted in the screening process. Thirty-one articles were included in the final analysis. Themes revealed that collectivistic values, cultural identities, and non-western regions were associated with public (others) stigma; mismatch of cultural values, minority groups, and North America, Asia, Oceania, and African regions were associated with higher perceived and self-stigma. We further mapped the themes into a proposed systemic cultural stigma model to integrate the dynamic intersection of cultural values, identity, and ecology. The cultural factors and their influence on stigma were then explained by drawing on two evolutionary theories: Cultural rationality theory and scapegoating theory. Lastly, we proposed culturally sensitive and responsive practices for stigma management at the community level, especially in non-Western regions during the pandemic recovery phase.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Throughout history, infectious diseases have emerged and spread across regions or populations as epidemics. “Epidemics occurring over a very wide area, crossing international boundaries and usually affecting a large number of people” are known as pandemics (Porta, 2014, p.209). Pandemics affect societies through physical illness and mortality, as well as a range of disruptions, including economic, social, and political consequences (Qiu et al., 2017). In particular, pandemics related to viral respiratory infections (VRIs), such as influenza (e.g., H1N1) or coronaviruses (e.g., severe acute respiratory syndrome [SARS], COVID-19), tend to trigger higher anxiety among the general population due to its life-threatening and highly contagious nature (Saeed et al., 2020). In addition, given VRIs’ ease of transmission through air and water droplets (Ong et al., 2020), public health control measures for VRI-induced pandemics generally require mass lockdown of public spaces and quarantine of high-risk groups. Such measures further reinforce public fear and isolation (Ren et al., 2020), which may leave individuals or groups associated with VRIs (e.g., countries of origin, highly infected regions, frontliners, patients, caretakers) especially vulnerable to stigmatization.

From the perspective of cultural psychology, scholars have proposed that culture plays an important role in stigmatizing attitudes and experiences, due to its underlying moral cognition (Yang et al., 2007). While there have been some commentaries highlighting the effect of culture on stigmatization during pandemics (e.g., Biswas et al., 2021; Bruns et al., 2020), there is still a gap in the synthesis of evidence-based studies to understand the cultural determinants of stigma during pandemics. Our study aimed to bridge this gap by conducting a systematic review of the published empirical articles in the past 21 years, to understand the role of culture on the perception of stigma towards others and self during VRIs pandemic. We aimed to advocate for culturally responsive and sensitive community services during the post-pandemic era, especially among the marginalized minorities.

Stigma as social constructs

Stigmatization is defined as the differentiation and labeling of a collective group of individuals based on their characteristics, attributes, qualities, or status (Goffman, 1968). This usually leads stigmatized individuals or groups to experience social exclusion, discrimination, humiliation, and marginalization from the mainstream (e.g., Saeed et al., 2020). At the broadest level, stigma can be categorized into two distinct constructs, namely, public stigma and self-stigma (Corrigan & Watson, 2002). From a social psychological perspective, we adopted this broad definition of stigma in our systematic review, where public stigma refers to an individual expressing stigmatizing attitudes and behaviors towards others, and self-stigma is the perception of being stigmatized.

Public stigma

Public stigma is defined as the negative beliefs and attitudes one holds that lead to fear, avoidance, rejection, or discrimination towards individuals with the disadvantaged condition (Corrigan & Penn, 1999; Parcesepe & Cabassa, 2013). In the context of the pandemic, the publicly stigmatized populations may include infected persons or those perceived to be at a higher risk of being infected, such as healthcare workers, family members, or people of a particular nationality or ethnicity, through associative stigma (Bhanot et al., 2021; Duan et al., 2020; Goffman, 1968; Hoppe, 2018). Public stigma, especially in the context of infectious diseases, can be explained through the evolutionary perspective of “othering,” with its function to protect oneself and one’s in-groups (Kurzban & Leary, 2001). Stigmatizing others is viewed as an act of adapting to increase the chances of both individual and in-group survival from the “perceived threat”—infected persons, or individuals or groups perceived to have associated attributes with the disease. To the individual, the phenomenon of separating between “them” and “us” allows the idea of distancing from perceived threat; the label “them” temporarily induces feelings of security and reduces fear and anxiety (Gilmore & Somerville, 1994; Saeed et al., 2020). This is especially prominent as epidemics and pandemics are characterized by and exacerbated by fear of the disease and uncertainty (Ren et al., 2020; Saeed et al., 2020). Hence, pandemics and virus outbreaks would be expected to be accompanied by social stigma toward others.

Self-stigma

In this study, self-stigma refers to the awareness and perceptions of negative attitudes, prejudice, or discrimination others hold towards them (Corrigan & Rao, 2012; Link, 1987). The self-stigma model proposed by Corrigan and Rao (2012) argues that self-stigma may extend beyond initial awareness and perception of receiving stigma, to individuals internalizing those beliefs, leading to lower self-esteem. Sullivan et al. (2014) explained that scapegoating may occur in response to uncontrollable situations, usually towards the minority out-group, with the displacement of anger toward tangible and controllable targets in response to the uncontrollable situation. This is obvious during the pandemic, when the infected or “associated” people were blamed and discriminated against (e.g., Yang et al., 2021). As such, self-stigma usually results from the public projection of fear during the pandemic, where the stigmatized group (either infected or associated) becomes the scapegoat and the out-group. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, some of the self-stigma experiences ranged from feeling ashamed, being blamed, and being rejected, isolated, and abandoned by close ones, as well as the larger community (Duan et al., 2020; Nursalam et al., 2020; Yuan et al., 2021). Effects of self-stigma can also be long-term, extending beyond surviving the disease and even the pandemic itself. For example, SARS survivors struggled against stigma from family and co-workers (Lee et al., 2005), and those who were COVID-19 positive or quarantined reported self-stigma (e.g., feeling abandoned) even after recovery (Lohiniva et al., 2021; Nursalam et al., 2020). Hence, it is important to study the nature and mechanism behind self-stigma during both the pandemic and the recovery phase.

Culture and stigma

On the socio-political level, previous research has identified several determinants that are associated with public stigma and self-stigma, including sociodemographic correlates such as education, health literacy, socio-economic status, gender, age, race/ethnicity, exposure to the virus, occupation as a healthcare worker, or the media (see, e.g., Yuan et al., 2021). We argue that culture is an additional factor that warrants a systematic study due to how the mechanism of culture interplays with pandemic stigma. While Link et al. (2004) viewed stigma as a universal phenomenon across different cultures and societies, Yang et al. (2007) highlighted that the experience and the endorsement of stigmatization could be very different and distinct, as stigmatizing actions, reasons, and outcomes differ based on culture. Moreover, some ethnic/racial identities or nationalities that are perceived to have a higher likelihood of being the carrier of virus or are believed to be the regional origin of the disease are highly stigmatized. (e.g., Bhanot et al., 2021; Hoppe, 2018). For example, literature reported that pandemics such as SARS and COVID-19 have been mainly associated with East Asians or Chinese, especially through media portrayal such as the news (e.g., He et al., 2020; Peprah & Gyasi, 2021).

On an individual level, there is some evidence that a person’s socio-cultural traits and norms may affect their perceptions and coping with a disease or illness. For example, Ji et al. (2020) reported how mainland Chinese had a more optimistic outlook towards the pandemic and the construct of suffering compared to the Euro-Canadians, potentially explained through dialectical thinking, whereby happiness and suffering co-exist in the Chinese population. Guan et al. (2020) also further explained how cultural constructs such as cultural orientation (e.g., collectivism/individualism—Hofstede, 1980; Triandis, 1995), cultural norms (e.g., tight/loose society—Gelfand et al., 2011), cultural-prone thinking styles (e.g., holistic/analytic—Nisbett et al., 2001) and self-construal (independent/ interdependent—Markus & Kitayama, 1991) impacted coping during the COVID-19 pandemic. Together, these different studies and approaches point to the close relationship between culture and perception of the pandemic, from the individual level to the national level, which warrants further studies from the cultural perspective (e.g., Yu et al., 2021).

Research aims

In this current review, we defined “culture” as a group of people sharing the same membership, such as ethnicity, race, language, and religion, as well as having shared beliefs, values, social norms, ideologies, traditions, or customs (Ferraro, 1998; Hofstede, 1991; Matsumoto et al., 1996). To date, a few published commentaries have attempted to describe the role of culture on public stigma during the COVID-19 pandemic, such as discriminating against or blaming a specific cultural group (e.g., Biswas et al., 2021; Bruns et al., 2020). While certain cultural groups are more vulnerable to social rejection during a pandemic, there is a gap about what are the prominent cultural determinants of the exhibition of stigma towards the “culturally other”. Moreover, as both culture and pandemic stigma are complex and multifaceted constructs, measures of these constructs are not consistent in the existing literature. A systematic review is ideal for synthesizing findings through an operationalized definition of these constructs to summarize how culture may influence stigma, with culture as the major theme or independent variable, and pandemic stigma (both self-stigma and public stigma) as the outcome or dependent variable. This type of review is needed to prevent or mitigate pandemic stigma in the future, by designing culturally responsive health campaigns and policies. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review that aimed to examine cultural factors associated with public stigma and self-stigma during VRI pandemics.

Method

Search strategy

We conducted a rigorous systematic review following PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al., 2009) in the following electronic databases: OVID (including APA PsycArticles Full Text, APA PsycINFO), Scopus, and all databases in Ebscohost (including CINAHL), with criteria set to include peer-reviewed full-text journals in English, from January 2000 to the first week of March 2022, with human participants. The search terms for the three keywords, 1) culture, 2) stigma, and 3) pandemic, were brainstormed and discussed between the authors based on the thesaurus and online searches, as shown in Table 1. We adopted wider definitions of all these three key terms to be exhaustive in our initial search, especially the types of pandemics being researched.

Study selection and eligibility criteria

Only studies fulfilling the following criteria were included:

-

(1) Full-text articles in the English language.

-

(2) Publications in peer-reviewed journals online from January 2000 to the third week of March 2022.

-

(3) Studies with human participants (i.e., content analysis of social media or news were excluded).

-

(4) Empirical studies—quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods (authors’ views, commentaries, theoretical papers, systematic reviews or meta-analyses, book chapters, conference proceedings, dissertations, and theses were excluded).

-

(5) Studies examining culture as an independent variable and stigma as a dependent variable in the context of a pandemic.

-

(6) Studies of viral respiratory infectious disease at pandemic or epidemic level only (i.e., coronavirus or influenza) (non-respiratory pandemic/epidemic such as Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) or Ebola infections were excluded).

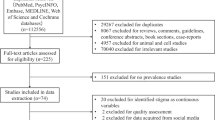

The screening process was reported in detail as per Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines (Moher et al., 2009), as shown in Fig. 1. The initial literature search yielded 70,737 research articles across the 3 databases: Ovid (N = 38,966), Ebscohost (N = 13,342) and Scopus (N = 18,429). The citations and abstracts were first imported into Endnote X9, which were further imported into the online Covidence platform to remove duplicates. After removing duplicates in Covidence, 50,251 research articles were left for further screening. The research team (consisting of the first and fourth authors and six research assistants) screened each title and abstract for relevance to the systematic review based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and excluded 49,932 articles in the preliminary screening (most of them were non-VRI diseases such as HIV). The team then reviewed the remaining 319 articles in full text where 286 articles were further excluded due to not fulfilling the screening criteria above.

Critical appraisal of the selected articles

The remaining 33 articles were further reviewed independently by the first and third authors, using Hawker’s critical appraisal ratings (Hawker et al., 2002), and rated as very poor, poor, fair, or good (score 1 to 4) for each of the following nine sections: abstract and title, introduction and aims, method and data, sampling, data analysis, ethics and bias, findings/results, transferability/generalizability, and implications and usefulness (see Table 2). The ratings from the initial review were averaged, and the discrepancy was reconciled by the second author. Two studies were excluded due to poor quality in their methodology (less than the cut-off score of 21, max = 36). Finally, 31 studies were included for the final synthesis in this study.

Qualitative coding of the findings

The above 31 articles were coded using a bottom-up inductive method through thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) by the first and second authors. Next, the themes were discussed and agreed upon by all authors following a consensual qualitative research (CQR) approach, using bottom-up coding (Hill et al., 2005) to minimize individual biases in interpretation, based on the research question.

Results

Study characteristics

As seen in Table 3, the majority of the studies were conducted in North America (n = 19), with 16 from the United States of America (USA), two from Canada, and one from the USA and Canada. Others came from diverse regions in Europe (n = 3), Asia (n = 6), Australia (n = 1), and South Africa (n = 1). One study included 173 countries worldwide, with regional comparisons. Most studies were conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic (n = 29), with the rest conducted during SARS (n = 1) or H1N1 (n = 1). Studies relied on quantitative (n = 17), qualitative (n = 10), and mixed (n = 4) methods. Most studies examined self-stigma (n = 26), while only seven examined public stigma (n = 7) as the outcome variable/s. Other details, including participants’ characteristics and measurements, are presented in Table 3.

Cultural factors and pandemic-related public stigma

From the seven studies that examined public stigma (e.g., discriminatory attitudes), four cultural factors were identified: Race or Ethnicity, Religious Identity, Collectivistic Values, and Residence in Non-Western Countries (see Table 4).

[Insert Table 4: Cultural Factors Associated with Public Stigma during Pandemics].

Race and ethnicity

As shown in Table 4, three studies found that being members of the majority race or ethnicity was associated with public stigma. In Wong and Sam’s study (2011), ethnicity was associated with the extent to which participants endorsed stigmatizing attitudes during the H1N1 pandemic. They found that among Malaysians, Malays endorsed the highest public stigma in the domain of fear (such as being afraid of those from overseas or eating outside) compared to Chinese and Indians. A qualitative study by Schmidt et al. (2020) also found that ethnic or racial identity was associated with public stigma towards other ethnicities during the COVID-19 pandemic, whereby some of the Blacks in South Africa believed COVID-19 to be a “White-mans’ disease” or a disease for those in China or Italy. They believed that the disease only affected “… upper-class people who travel a lot”, “it was for the White people” or that “it doesn’t affect Black people, we have strong genes…” (Schmidt et al., 2020, p.12). On the other hand, a study in China by Jiang et al. (2021) found that ethnic minorities expressed higher public stigma, such as fear and avoidance towards COVID-19 patients and people from Wuhan, compared to the Han majority. Overall, these studies demonstrated that racial and ethnic identities were associated with negative perceptions of others who were affiliated with the pandemic, especially those from other racial groups.

Religious identity

Two studies found different religious identities within a country were associated with differences in public stigma during the COVID-19. In Lebanon, those who identified as a Muslim or a Druze reported higher discriminatory attitudes towards those infected with COVID-19 compared to the Christians (Haddad et al., 2021). A study in India by Islam et al. (2021) found that while Hindus perceived Muslims to be responsible for the spread of the COVID-19, Muslims did not hold this perception towards the Hindus.

Collectivistic values

Findings from Ahuja et al. (2020) showed a positive relationship between collectivism and pandemic-related public stigma in India, where collectivism was defined as the extent to which family and society needs take importance over an individual’s needs (Kim et al., 2016). They found that the more the non-Muslim participants endorsed collectivist values, the more they expressed public stigma (blaming and attributing the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic) towards Muslims in India.

Non-Western countries

A global survey conducted by Dye et al. (2020) across 173 countries found differences in COVID-19 related public stigma across different geographical regions. In comparison to participants from Europe, Northern America, or Oceania, participants from Non-western countries such as Asia, Africa, Latin America, and Caribbean regions were more likely to believe that individuals in their community had a negative perception of those who were infected or associated with COVID-19. They were also more likely to believe that people lost status and respect in the community when they tested COVID-19 positive compared to participants in Europe, Northern America, or Oceania. However, Dye and colleagues (2020) did not explain why there were differences across the regions.

Cultural factors and pandemic-related self-stigma

Out of 26 articles, we identified five cultural factors which had self-stigma during the pandemic (e.g., perceived stigma/discrimination, harassment) as the outcome variable: Minority by Race, such as the overseas Chinese, Minority by Religion, Minority in Spoken Language, Cultural Values that conflicted with the Dominant Society, and Countries in Northern America, Africa, Oceania, and Asian regions (see Table 5).

[Insert Table 5: Cultural factors Associated with Self-Stigma related to Pandemics].

Ethnic Minorities, especially Chinese in Western Countries

This was the most frequently identified cultural factor (N = 23). In North America (the USA and Canada), several studies found that Asians reported the highest degree of being stigmatized or discriminated against during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to other races, especially Whites (Inman et al., 2021; Miconi et al., 2021a, 2021b; Pan et al., 2021) and other People of Color (POC), such as Blacks or Latino/a (Molock & Parchem, 2021), or Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders (Park et al., 2022). Generally, in the US, Asians were seen to experience higher self-stigma compared to non-Asians during the COVID-19 pandemic (Kim et al., 2022). Moreover, some Asians attributed self-stigma to their ethnicity or race. Dye et al. (2020) reported that across 173 countries Asian and Chinese participants felt stigmatized during the COVID-19 pandemic due to their ethnicity. For instance, a Southeast Asian participant in Europe stated, “I am Asian…people treated me badly and avoided me.” (Dye et al., 2020, p.10). Similar findings were echoed among Chinese or Asians in France, and the US, whereby their Asian physical appearance, as well as China being the pandemic origin, were some of the reasons for feeling stigmatized and being discriminated against during the COVID-19 pandemic (Ji & Chen, 2022; Oh & Min, 2022; Wang et al., 2021). Interestingly, Ji and Chen (2022) indicated that the Chinese international students not only felt stigmatized by the majority in the US, but also felt blamed and received less support from the Chinese back in China, as they were told it was their own choice and responsibility for leaving China and studying in the US.

Moreover, self-stigma during the pandemic was not limited to Asians per se, as other ethnic minorities also reported higher experiences of discrimination compared to the majority in the USA (e.g., Le et al., 2022, Shah et al., 2021, Strassle et al., 2022, & Tan & Umamaheswar, 2021). For instance, ethnic minorities such as Blacks and South Asians in the USA reported similar narratives where they felt that they were stigmatized by the public and the community around them such as, “I think somehow there’s always this narrative that we’re the other…We have COVID, and nobody else seems to have it. And we’re the ones that are spreading it around.” (Vandrevala et al., 2022, p.146). Interestingly, not only were particular racial labels associated with intensified self-stigma, but personal identification with the racial label was found to be associated with a higher level of self-stigma. For instance, Zong et al. (2021) found that those Chinese American adolescents who identified themselves most as “Chinese” (participation in Chinese culture) and lowest as “American” reported the highest level of racial discrimination experiences, compared to their counterparts who identified either as bicultural or had a low level of identification with both cultures. Increased self-stigma among ethnic minorities was not limited to COVID-19 pandemic, as an earlier qualitative study during SARS also found that residents of the Chinatown in New York, USA reported feeling stigmatized due to their ethnicity (Eichelberger, 2007), such as a participant stated: “I did feel more self-conscious that I was getting these looks because I was—I am Asian, Asian–American. That was hard for me.” (p. 1290). In short, the studies showed that ethnic identity, especially being the minority, was associated with higher self-stigma during a pandemic.

Religious identity, especially among the minorities

Three studies found that minority religious groups were stigmatized during the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, in Quebec, Canada, individuals who self-reported as “other” religion reported the highest discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic, followed closely by Islam and then Christianity, Atheism, and Judaism (Miconi et al., 2021a). Moreover, in Dye and colleagues’ (2020) study, a Muslim participant wrote that they felt stigmatized in a South Asian country, “As I belong to a particular religion [Islam], the people near my home keep on bullying us for the coronavirus, which is not fair” (Dye et al., 2020, p.10). Weiden et al. (2021) found that a third of the participants from the cultural minority group in Israel, Ultra-orthodox Jews, perceived they experienced microaggressions due to their religious identity during the COVID-19 pandemic. Interestingly, Haddad et al. (2021) found that Muslims in Lebanon (the majority) who were diagnosed with COVID-19 were more likely to report feeling isolated by others or having higher internalized shame concerning their condition compared to Christians who were diagnosed.

Being a minority by spoken language

Self-stigma was not only associated with religious minorities but also with those who were a minority by spoken language. In the same study conducted in Quebec, Canada, Miconi et al. (2021a) found that those who were English-speaking were more likely to report experiences of discrimination during COVID-19 compared to those who were bilingual (English and French) or French-speaking only. As Quebec is a French dominant region, this implies that those who could not speak the French language (most likely a foreigner) faced higher self-stigma than others during the pandemic.

Cultural values conflict with the dominant society

A qualitative study by Ma and Zhan (2020) found that a mismatch in cultural values was associated with stigma experiences. They interviewed Chinese international students who felt stigmatized by Americans in the USA. Chinese students reported that they were being stigmatized due to the mismatch in cultural values and norms between the Chinese and mainstream American society, which resulted in differences in health behaviors and beliefs during the pandemic. For instance, an interviewee mentioned, “American culture values human rights and freedom. The American people do not listen to their government, even if their government asks them to do something. Chinese people tend to listen.” and another, “…Americans look…to me…they live a very independent and individualistic life…” (Ma & Zhan, 2020, p.14). Another participant quoted their American Professor’s judgment of them for wearing masks, “Why are you wearing masks? You are selfish. You should leave the masks to doctors” (Ma & Zhan, 2020, p.11).

Countries and regions

Finally, one study found that self-reported discrimination differed among countries. Countries from African, Asian, Northern American, and Oceania regions reported higher experiences of self-stigma, represented by COVID-19 related bullying/discrimination, compared to those in Latin America and Europe (Dye et al., 2020).

Discussion

The current systematic review identified a number of cultural factors associated with public stigma and self-stigma during pandemics caused by VRI. Previous researchers have highlighted that stigma is a complex and multi-faceted phenomenon, with factors influencing stigma at different levels, including culture (e.g., Link & Phelan, 2001). Erez and Gati (2004) illustrated the intersection of a multi-level culture model from individual level to group, organizational, national to global levels. However, there has been no integrative model of how culture at different levels interact with stigma specifically. Hence, based on our findings, we attempted to construct the cultural factors we identified into a multi-level systemic model of cultural levels relevant to pandemic stigma. This consisted of culture from the micro-individual domain, meso-level shared cultural group identity, and the larger macro-society/ecology one resides in. The micro domain describes the influence of culture at the individual level, such as cultural values or beliefs. Next, at the meso-level of shared identity, we identified cultural group identities such as race/ethnicity, religion, or shared language, which influenced pandemic stigma. Lastly, the influence of culture at the regional or country level was mapped onto the macro-level domain, termed cultural ecology. We label this model tentatively as a “systemic cultural stigma model” (see Fig. 2).

Here, we discuss this cultural stigma model in relation to both public stigma and self-stigma during the pandemic from the perspective of evolutionary cognition from Strong Ties Weak Ties (STWT) cultural rationality theory (Sundararajan, 2020; Yeh et al., 2022) and social group conflicts from scapegoating theory (Allport, 1954). Then, we discuss the implications of our findings for community healthcare.

Cultural domains and public stigma

As shown in the systemic cultural stigma model in Fig. 2, collectivistic values (individual level), ethnic/racial and religious identity (shared cultural identity), and non-western countries (cultural ecology) were associated with pandemic-related public stigma. These cultural factors could be interpreted through cultural niche-rationality theory, recently proposed by Sundararajan ‘s (2020). Cultural rationality theory posits how individuals differ in their cognition, such as reasoning about the world based on their evolutionary ecology, which influences the subsequent choice of survival behaviors (Morfett, 2018; Sundararajan, 2020). A Strong-Ties based community is described as comprised of close-knit relationships of family or kinship, with a cognitive orientation to external cues and resources (i.e., relying on strong-ties networks during hardship, shared responsibilities, and decision making), whereas weak-ties networks refer to distant relationship networks, such as acquaintances or strangers (Sundararajan, 2020; Ting & Sundararajan, 2018). With this foundation, STWT cultural rationality theory posits that an individual with a more dominant strong-ties rationality is more holistic in their cognitive style, where they perceive self in relation to those around them, aligning with the concept of related others (Sundararajan, 2020). Hence, in strong-ties dominant societies, individuals prioritize safety and wellness of family, kinship, and close friends, with fewer considerations given to those perceived as threats (regardless of in-group out-group membership), which could result in the social rejection of the latter. Values such as collectivism are privileged among strong-ties dominant societies, while individualism is privileged among weak-ties dominant societies (Sundararajan & Yeh, 2021). Research has also identified some associations between certain religions or ethnicities that historically embody kinship and bloodline as important and their members being more dominant in strong-ties rationality (Thong et al., 2022; Ting & Zhang, 2021; Yeh et al., 2022).

Public stigma, especially in the context of infectious diseases, has previously been explained through evolutionary needs, with its function to preserve group survival by distancing from those who are perceived as threats, namely the out-groups (Gilmore & Somerville, 1994; Kurzban & Leary, 2001; Saeed et al., 2020). During disasters such as pandemics, a society becomes tighter in its social norms, expecting higher conformity from its members, due to the commonly perceived threat of a contagious virus (Gelfand et al., 2021). STWT cultural rationality theory (Sundararajan, 2020) further suggests this type of reasoning is more privileged by strong-ties societies, following the evolutionary discourse, where tribal survival needs are prioritized over individual survival.

We found that the cultural factors associated with public stigma represented characteristics of strong-ties rationality at the micro-level through to strong-ties society at the macro-level. At the individual level, one study showed an association between collectivistic values and public stigma (Ahuja et al., 2020). At the group identity level, strong-ties ethnic identity was seen to have led to the social rejection of others who were more susceptible to the virus (Jiang, et al., 2021; Schmidt et al., 2020). In addition, we also found that religious groups in strong-ties societies were associated with higher public stigma toward the perceived threat, COVID-19 infected or affiliated persons (Haddad et al., 2021; Islam et al., 2021). Lastly, at the cultural ecology level, a study found higher public stigma among strong-ties countries, such as in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean regions compared to the weak-ties countries such as Europe, Northern America, or Oceania (Dye et al., 2020). The former regions have historically been considered as collectivistic societies in previous cross-cultural psychology literatures (Eaton & Louw, 2000; Holloway, 1990; Triandis, 2015). Past literature (e.g., Krendl & Pescosolido, 2020) on mental illness stigma has also corroborated our findings demonstrating a higher endorsement of stigma in Eastern countries (strong-ties characteristics) even towards their own in-group members due to the perceived threat to their group dynamics compared to Western countries (weak-ties characteristics). Overall, evolutionary cognition and niche could well explain why these strong-ties related cultural features are associated with public stigma, due to their association with the conservation of bloodline and in-group survival.

Culture domains and self-stigma

As shown in our cultural stigma model, having conflicting or mismatching cultural values with the dominant society (individual level), or being a minority by ethnicity, religion, or language (shared cultural identity), or particular countries (cultural ecology) were cultural factors associated with pandemic-related self-stigma. We propose this pattern of self-stigma being perceived primarily among the minorities could be explained using scapegoating theory (e.g., Allport, 1954; Sullivan et al., 2014). According to Allport (1954), during social turbulence, “scapegoating” occurs as people displace their anger and frustration on those perceived as being minority group members, usually based on common cultural labels such as ethnicity or religion. Sullivan et al. (2014) further posited that the mechanism of displacing blame on tangible and controllable targets when situations are perceived as out of control (e.g., a crisis) brings a temporary sense of control to those of the majority. Hence, during a disastrous pandemic, this could result in minority cultural groups being the scapegoats, subject to self-stigma. We found that the majority of the articles in our review pointed to Chinese or Asian Americans as the ethnic minority group who felt most stigmatized or discriminated against during the pandemic due to their behavior of wearing a mask (Ma & Zhan, 2020), their physical appearance, or their affiliation with countries in the Asian region where the pandemic was believed to have originated (e.g., Dye et al., 2020; Eichelberger, 2007; Miconi et al., 2021a, b; Molock & Parchem, 2021; Oh & Min, 2022). Moreover, other ethnic minorities, such as Persons of Color in the US, also reported higher self-stigma, potentially as the result of scapegoating (e.g., Le et al. 2022; Tan & Umamaheswar, 2021). Other forms of cultural identity were also associated with higher self-stigma and discrimination during the pandemic, such as those who were members of a minority by religion or spoken language (Miconi et al., 2021a, b; Weiden et al., 2021). Especially in the context of religion, both dominant and non-dominant religious groups reported higher self-stigma (e.g., Haddad et al., 2021, Islam et al., 2021), suggesting religious identity is susceptible to self-stigma during a pandemic regardless of their social status. Lastly, in the larger ecology domain, one study found differences in the level of self-stigma across countries in different regions (Dye et al., 2020).

Implications of our study for communal well-being

Our findings regarding cultural factors associated with stigma during the pandemic led to the proposed cultural stigma model introduced above. Despite the need for more research in certain cultural domains, our proposed model may guide the design of public health interventions during the recovery stage of the pandemic. We suggest national policies should consider culturally-responsive approaches to increase the effectiveness of anti-stigma campaigns in the community. For instance, in strong-ties societies, policymakers could reframe anti-stigma interventions as “communal thriving”, which promotes the idea of “togetherness”. To overcome disproportionate fear and perceived threat of marginalized groups, government agencies and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) could emphasize messages and awareness campaigns on practical and tangible methods of keeping safe as a whole community regardless of group membership during the pandemic for the larger good (e.g., “We are all one family” or “We are all in the same boat”). On the other hand, since cultural minority groups in general perceived higher self-stigma, national bodies such as the health ministry through national policies or media could advocate for their pandemic control campaigns to be more culturally responsive towards less-represented groups (e.g., ethnic minorities, migrant workers, refugees). Moreover, during future pandemics, healthcare providers (e.g., public health officials, mental health professionals) could focus on increasing awareness of the scapegoating phenomena, introducing cross-cultural empathy exercises, and increasing the internal locus of control within individuals in the weak-ties society, to help reduce displaced anger and frustration toward minority groups. Overall, with more culturally responsive health campaigns, we anticipate a better quality of life at the individual level, as well as positive community-wide benefits, with fewer instances of isolation and division within the society.

Gaps in the literature and recommendations for future studies

Our review highlighted that there is limited rigorous and empirical literature exploring the role of culture in pandemic-related stigma. While differences in cultural characteristics such as ethnocultural identity associated with public stigma or self-stigma were reported, cultural theories explaining those observed differences were absent. In addition, the majority of the reviewed articles only used self-reported cultural characteristics. There is a need for researchers to also use cultural scales to assess participants’ underlying cultural values (e.g., collectivism/individualism), rationality (i.e., STWT), thinking styles, etc. Moreover, the self-reported cultural characteristics, such as ethnicities, were compared with unequal sample sizes which, while reflective of the population in those countries, may limit the power of the analyses. As the current review led to our proposed cultural stigma model (see Fig. 2), we recommend that future studies consider assessing all three domains to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the role of culture. Specifically, more studies could involve cultural measures in both the individual and ecology domains, to examine the dynamic interaction between the different cultural domains. There were also limited studies examining public stigma, as the majority studied only self-stigma during the pandemic. Understanding both constructs of stigma is important, as the systematic review showed that the cultural factors associated with each differed. Furthermore, there were multiple stigma scales adopted in the different studies, which only tapped into certain aspects of stigma, such as fear (e.g., Wong & Sam, 2011) or discriminatory treatment (e.g., Dye et al., 2020), making comparisons across studies difficult. Some scales were only validated in one single national sample. Hence, we also recommend either exploring stigma concepts that may be specific to a culture through a bottom-up approach, or developing and validating standardized pandemic stigma scales for future research that are suitable for cross-cultural comparisons.

Limitations of this study

As this systematic review only included journals published in English, it is possible we may have missed indigenous or international papers published in other languages. Moreover, due to the limited representation of countries (e.g., most studies were from the USA), there is a need to exercise caution in interpreting the current review, as there is a limit to the generalizability of the findings. Regarding the systemic cultural stigma model, there was only one study each that mapped onto the cultural values and ecology domain, due to the limited availability of empirical studies in these cultural domains relating to pandemic stigma. Lastly, as this study only reviewed cultural factors and their association to stigma, other possible contributing factors to stigma, such as sociodemographic variables (e.g., age, gender, SES, political affiliation) or personal variables (beliefs and motivation), have not been taken into consideration.

Conclusion

The findings from our systematic review highlighted the interplay between culture and pandemic stigma, as well as informing implications for interventional campaigns at multicultural societies. We examined the intersectionality of three cultural domains, individual cultural values, cultural identity, and cultural ecology, and incorporated STWT cultural rationality theory and scapegoating theory, to draw on both evolutionary and sociological perspectives to explain how culture may affect pandemic stigma. We also highlighted the need for more mixed-method research in non-Western societies to look at both types of stigma. Finally, we advocate that it is essential to promote culturally-responsive stigma interventions in the community, informed by research, to increase the well-being and inclusivity of minority groups during a pandemic.

Data availability

All articles involved in this systematic review are available through e-databases. The data generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ahuja, K. K., Banerjee, D., Chaudhary, K., & Gidwani, C. (2020). Fear, xenophobia and collectivism as predictors of well-being during coronavirus disease 2019: An empirical study from India. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 67(1), 46–53.

Allport, G. W. (1954). The Nature of Prejudice. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc.

Berger, B. E., Ferrans, C. E., & Lashley, F. R. (2001). Measuring stigma in people with HIV: Psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Research in Nursing & Health, 24(6), 518–529. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.10011

Bhanot, D., Singh, T., Verma, S. K., & Sharad, S. (2021). Stigma and discrimination during COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 577018. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.577018

Biswas, D., Chatterjee, S., & Sultana, P. (2021). Stigma and fear during COVID-19: Essentializing religion in an Indian context. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 8, 130. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00808-8

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bruns, D. P., Kraguljac, N. V., & Bruns, T. R. (2020). COVID-19: Facts, cultural considerations, and risk of stigmatization. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 31(4), 326–332. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659620917724

Corrigan, P. W., & Penn, D. L. (1999). Lessons from social psychology on discrediting psychiatric stigma. The American Psychologist, 54(9), 765–776. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.54.9.765

Corrigan, P. W., & Rao, D. (2012). On the self-stigma of mental illness: Stages, disclosure, and strategies for change. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 57(8), 464–469. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371205700804

Corrigan, P. W., & Watson, A. C. (2002). Understanding the impact of stigma on people with mental illness. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 1(1), 16–20.

Chowdhury, M. R. K., Rahman, M. S., Mondal, M. N. I., Sayem, A., & Billah, B. (2015). Social Impact of Stigma Regarding Tuberculosis Hindering Adherence to Treatment: A Cross Sectional Study Involving Tuberculosis Patients in Rajshahi City. Bangladesh. Japanese Journal of Infectious Diseases, 68(6), 461–466. https://doi.org/10.7883/yoken.JJID.2014.522

Datiko, D. G., Jerene, D., & Suarez, P. (2020). Stigma matters in ending tuberculosis: Nationwide survey of stigma in Ethiopia. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 190–191. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7915-6

Do Duy, C., Nong, V. M., Van Ngo, A., Doan Thu, T., Do Thu, N., & Nguyen Quang, T. (2020). COVID-19-related stigma and its association with mental health of healthcare workers after quarantine in Vietnam. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 74(10), 566–568. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.13120

Dollmann, J., & Kogan, I. (2021). COVID-19–associated discrimination in Germany. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 74, 100631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2021.100631

Duan, W., Bu, H., & Chen, Z. (2020). COVID-19-related stigma profiles and risk factors among people who are at high risk of contagion. Social Science & Medicine, 266, 113425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113425

Dye, T. D., Alcantara, L., Siddiqi, S., Barbosu, M., Sharma, S., Panko, T., & Pressman, E. (2020). Risk of COVID-19-related bullying, harassment and stigma among healthcare workers: An analytical cross-sectional global study. BMJ Open, 10(12), e046620. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046620

Eaton, L., & Louw, J. (2000). Culture and self in South Africa: Individualism-collectivism predictions. The Journal of Social Psychology, 140(2), 210–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224540009600461

Eichelberger, L. (2007). SARS and New York’s Chinatown: The politics of risk and blame during an epidemic of fear. Social Science & Medicine, 65, 1284–1295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.04.022

Erez, M., & Gati, E. (2004). A Dynamic, multi-level model of culture: From the micro level of the individual to the macro level of a global culture. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 53(4), 583–598. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2004.00190.x

Ferraro, G. (1998). The Cultural Dimension of International Business. 3rd Edition. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Gelfand, M. J., Jackson, J. C., Pan, X., Nau, D., Pieper, D., Denison, E., Dagher, M., Van Lange, P. A. M., Chiu, C., & Wang, M. (2021). The relationship between cultural tightness–looseness and COVID-19 cases and deaths: A global analysis. The Lancet. Planetary Health, 5(3), e135–e144. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30301-6

Gelfand, M. J., Raver, J. L., Nishii, L., Leslie, L. M., Lun, J., Lim, B. C., Duan, L., Almaliach, A., Ang, S., Arnadottir, J., Aycan, Z., Boehnke, K., Boski, P., Cabecinhas, R., Chan, D., Chhokar, J., D’Amato, A., Ferrer, M., Fischlmayr, I. C., & Yamaguchi, S. (2011). Differences between tight and loose cultures: A 33-nation study. Science (american Association for the Advancement of Science), 332(6033), 1100–1104. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1197754

Gilmore, N., & Somerville, M.A. (1994). Stigmatization, scapegoating, and discrimination in sexually transmitted diseases, overcoming “them” and “us”.Social Science & Medicine, 39, 1339–1358.

Goffman, E. (1968). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Penguin.

Green, G. (1995). Attitudes towards people with HIV: Are they as stigmatizing as people with HIV perceive them to be? Social Science and Medicine, 41(4), 557–568.

Guan, Y., Deng, H., & Zhou, X. (2020). Understanding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on career development: Insights from cultural psychology. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 119, 103438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103438

Haddad, C., Malhab, S. B., Malaeb, D., Sacre, H., Saadeh, D., Mourtada, V., & Salameh, P. (2021). Stigma toward people with COVID-19 among the Lebanese population: A cross-sectional study of correlates and mediating effects. BMC Psychology, 9(1), 1–164. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-021-00646-y

Hawker, S., Payne, S., Kerr, C., Hardey, M., & Powell, J. (2002). Appraising the evidence: Reviewing disparate data systematically. Qualitative Health Research, 12(9), 1284–1299. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732302238251

He, D., Zhao, S., Lin, Q., Zhuang, Z., Cao, P., Wang, M. H., & Yang, L. (2020). The relative transmissibility of asymptomatic COVID-19 infections among close contacts. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 94, 145–147.

Hennein, R., Tineo, P., Bonumwezi, J., Gorman, H., Nguemeni, T., Max, J., & Lowe, S. R. (2021). “They Wanted to Talk to a ‘Real Doctor’”: Predictors, Perpetrators, and Experiences of Racial and Ethnic Discrimination Among Healthcare Workers. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 37(6), 1475–1483. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07143-3

Hill, C. E., Knox, S., Thompson, B. J., Williams, E. N., Hess, S. A., & Ladany, N. (2005). Consensual qualitative research: An update. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52, 196–205. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033361

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Sage.

Hofstede, G. (1991). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. HarperCollinsBusiness.

Holloway, J. E. (1990). The origins of African-American culture. In J. E. Holloway (Ed.), Africanisms in American culture (pp. 1–18). Indiana University Press.

Hoppe, T. (2018). Spanish flu: When infectious disease names blur origins and stigmatize those infected. American Journal of Public Health, 108(11), 1462–1464. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304645

Huynh, Q. L., Benet-Martınez, V., & Nguyen, A. M. D. (2018). Measuring variations in bicultural identity across US ethnic and generational groups: Development and validation of the Bicultural Identity Integration Scale-Version 2 (BIIS-2). Psychological Assessment, 30(12), 1581–1596. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000606

Inman, E. M., Bermejo, R. M., McDanal, R., Nelson, B., Richmond, L. L., Schleider, J. L., & London, B. (2021). Discrimination and psychosocial engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic. Stigma and Health (Washington, D.C.), 6(4), 380–383. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000349

Islam, A., Pakrashi, D., Vlassopoulos, M., & Wang, L. C. (2021). Stigma and misconceptions in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic: A field experiment in India. Social Science & Medicine, 278, 113966–113966. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113966

Jesuthasan, J., Powell, R. A., Burmester, V., & Nicholls, D. (2021). We weren’t checked in on, nobody spoke to us’: An exploratory qualitative analysis of two focus groups on the concerns of ethnic minority NHS staff during COVID-19. British Medical Journal Open, 11(12), e053396–e053396. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053396

Ji, L. J., Khei, M., Yap, S., Wang, X., Zhang, Z., & Hou, Y. (2020). Cultural differences in the construal of suffering and the COVID-19 pandemic. Social Psychological and Personality Science. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550620958807

Ji, Y., & Chen, Y. W. (2022). “Spat On and Coughed At”: Co-Cultural Understanding of Chinese International Students’ Experiences with Stigmatization during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Health Communication, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2022.2045069

Jiang, T., Zhou, X., Lin, L., Pan, Y., Zhong, Y., Wang, X., & Zhu, H. (2021). COVID-19-related stigma and its influencing factors: A nationwide cross-sectional study during the early stage of the pandemic in China. British Medical Journal Open, 11(8), e048983–e048983. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-048983

Kim, H. S., Sherman, D. K., & Updegraff, J. A. (2016). Fear of Ebola: The influence of collectivism on xenophobic threat responses. Psychological Science, 27(7), 935–944.

Kim, M., Liu, S., Lee, Y., Shrader, C. H., & Kanamori, M. (2022). COVID-19 Related Racial Discrimination in Small Asian Communities: A Cross Sectional Study. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 24, 38–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-021-01295-4

Krendl, A. C., & Pescosolido, B. A. (2020). Countries and Cultural Differences in the Stigma of Mental Illness: The East-West Divide. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 51(2), 149–167. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022119901297

Kurzban, R., & Leary, M. R. (2001). Evolutionary origins of stigmatization: The functions of social exclusion. Psychological Bulletin, 127(2), 187–208. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.127.2.187

Landrine, H., Klonoff, E. A., Corral, I., Fernandez, S., & Roesch, S. (2006). Conceptualizing and measuring ethnic discrimination in health research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 29(1), 79–94.

Le, P. D., Misra, S., Hagen, D., Wang, S. M., Li, T., Brenneke, S. G., Yang, L. H., & Goldmann, E. (2022). Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Related Discrimination and Mental Health in Five U.S. Southern Cities. Stigma and Health. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000351

Lee, S., Chan, L. Y., Chau, A. M., Kwok, K. P., & Kleinman, A. (2005). The experience of SARS-related stigma at amoy gardens. Social Science & Medicine, 61(9), 2038–2046. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.04.010

Li, H., & Chen, X. (2021). From “Oh, you’re Chinese . . . ” to “No bats, thx!”: Racialized Experiences of Australian-Based Chinese Queer Women in the Mobile Dating Context. Social Media + Society, 7(3), 205630512110353. https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211035352

Link, B.G. (1987). Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: An assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection. American Sociological Review, 52(1), 96–112. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2095395

Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 363–385. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363

Link, B. G., Yang, L. H., Phelan, J. C., & Collins, P. Y. (2004). Measuring mental illness stigma. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 30(3), 511–541. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007098

Lohiniva, A. L., Dub, T., Hagberg, L., & Nohynek, H. (2021). Learning about COVID-19-related stigma, quarantine and isolation experiences in Finland. PLoS ONE, 16(4), e0247962. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247962

Ma, Y., & Zhan, N. (2020). To mask or not to mask amid the COVID-19 pandemic: How Chinese students in America experience and cope with stigma. Chinese Sociological Review. 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/21620555.2020.1833712.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224–253. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224

Matsumoto, D., Kudoh, T., & Takeuchi, S. (1996). Changing patterns of individualism and collectivism in the United States and Japan. Culture & Psychology, 2(1), 77–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X9621005

Miconi, D., Li, Z. Y., Frounfelker, R. L., Santavicca, T., Cénat, J. M., Venkatesh, V., & Rousseau, C. (2021). Ethno-cultural disparities in mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study on the impact of exposure to the virus and COVID-19-related discrimination and stigma on mental health across ethno-cultural groups in Quebec (Canada). BJPsych open, 7(1), e14. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2020.146

Miconi, D., Li, Z. Y., Frounfelker, R. L., Venkatesh, V., & Rousseau, C. (2021b). Socio-cultural correlates of self-reported experiences of discrimination related to COVID-19 in a culturally diverse sample of Canadian adults. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 81, 176–192.

Miller, M. J., Kim, J., Chen, G. A., & Alvarez, A. N. (2012). Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses of the Asian American racism-related stress inventory. Assessment, 19(1), 53–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191110392497

Moffett, M. W. (2018). The human swarm: How our societies arise, thrive, and fall. Basic Books.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ, 339(7716), 332–336. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535

Molock, S. D., & Parchem, B. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on college students from communities of color. Journal of American College Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2020.1865380

Nadal, K. L. (2011). The Racial and Ethnic Microaggressions Scale (REMS): Construction, reliability, and validity. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(4), 470–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025193

Nisbett, R. E., Peng, K., Choi, I., & Norenzayan, A. (2001). Culture and systems of thought: Holistic versus analytic cognition. Psychological Review, 108(2), 291–310. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.108.2.291

Nursalam, N., Sukartini, T., Priyantini, D., Mafula, D., & Efendi, F. (2020). Risk factors for psychological impact and social stigma among people facing COVID-19: A systematic review. Sys Rev Pharm, 11(6), 1022–1028.

Oh, D. C., & Min, S. J. (2022). COVID-19 and the Fourth Estate: Asian American Journalists’ Gendered Racial Harms and Racial Activation During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 99(1), 113–134. https://doi.org/10.1177/10776990211068408

Ong, C. W. M., Migliori, G. B., Raviglione, M., MacGregor-Skinner, G., Sotgiu, G., Alffenaar, J., Tiberi, S., Adlhoch, C., Alonzi, T., Archuleta, S., Brusin, S., Cambau, E., Capobianchi, M. R., Castilletti, C., Centis, R., Cirillo, D. M., D'Ambrosio, L., Delogu, G., Esposito, S. M. R, … Goletti, D. (2020). Epidemic and pandemic viral infections: Impact on tuberculosis and the lung. The European Respiratory Journal, 56(4). https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01727-2020

Park, V. M. T., Dougan, M. M., Meyer, O. L., Nam, B., Tzuang, M., Park, L. G., Vuong, Q., Bang, J., & Tsoh, J. Y. (2022). Discrimination Experiences during COVID-19 among a National, Multi-Lingual, Community-Based Sample of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders: COMPASS Findings. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(2), 924. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020924

Pan, S. W., Shen, G. C., Liu, C., & Hsi, J. H. (2021). Coronavirus stigmatization and psychological distress among Asians in the United States. Ethnicity & Health, 26(1), 110–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2020.1849570

Parcesepe, A. M., & Cabassa, L. J. (2013). Public stigma of mental illness in the United States: A systematic literature review. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 40(5), 384–399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-012-0430-z

Peprah, P., & Gyasi, R. M. (2021). Stigma and COVID-19 crisis: A wake-up call. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 36(1), 215–218. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.3065

Porta, M. (2014). A dictionary of epidemiology (6th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Qiu, W., Rutherford, S., Mao, A., & Chu, C. (2017). The pandemic and its impact. Health, Culture and Society, 9, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.5195/hcs.2017.221

Ren, S. Y., Gao, R. D., & Chen, Y. L. (2020). Fear can be more harmful than the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in controlling the corona virus disease 2019 epidemic. World Journal of Clinical Cases, 8(4), 652–657. https://doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i4.652

Saeed, F., Mihan, R., Mousavi, S. Z., Reniers, R. L., Bateni, F. S., Alikhani, R., & Mousavi, S. B. (2020). A narrative review of stigma related to infectious disease outbreaks: What can be learned in the face of the Covid-19 pandemic? Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 565919. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.565919

Schmidt, T., Cloete, A., Davids, A., Makola, L., Zondi, N., & Jantjies, M. (2020). Myths, misconceptions, othering and stigmatizing responses to Covid-19 in South Africa: A rapid qualitative assessment. PLoS ONE., 15(12), e0244420. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244420

Sellers, R. M., Rowley, S. A. J., Chavous, T. M., Shelton, J. N., & Smith, M. A. (1997). Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity: A preliminary investigation of reliability and construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(4), 805–815. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.73.4.805

Shah, G. H., Rochani, H. D., Telfair, J., Ayangunna, E., & Skuraton, G. (2021). College Students’ Experiences of Race-Related Bias or Hatred in Their Lifetimes and COVID-19 Era. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 27(3), 258–267. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000001351

Shang, Z., Kim, J. Y., & Cheng, S. O. (2021). Discrimination experienced by Asian Canadian and Asian American health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. CMAJ Open, 9(4), E998–E1004. https://doi.org/10.9778/cmajo.20210090

Shariff-Marco, S., Breen, N., Landrine, H., Reeve, B. B., Krieger, N., Gee, G. C., Williams, D. R., Mays, V. M., Ponce, N. A., Alegria, M., Liu, B., Willis, G., & Johnson, T. P. (2011). Measuring Everyday Racial/Ethnic Discrimination in Health Surveys: How Best to Ask the Questions, in One or Two Stages, Across Multiple Racial/Ethnic Groups? Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 8, 159–177. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742058X11000129

Soin ́e, H., Arnold, L., Dollmann, J., Kriegel, L., & Weißmann, M. (2021). Children of immigrants longitudinal survey in four European countries – Germany. Technical report. COVID-19 supplementary survey – CILS4COVID – 2020, v5.0.0. Mannheim: Mannheim University.

Stangl, A., Brady, L., Fritz, K. (2018). STRIVE Technical brief: Measuring HIV stigma and discrimination; International Center for Research on Women, Washington D.C, USA. http://strive.lshtm.ac.uk/system/files/attachments/STRIVE%20stigma%20measurement.pdf

Sternthal, M. J., Slopen, N., & Williams, D. R. (2011). Racial disparities in health: How Much Does Stress Really Matter? Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 8(1), 95–113. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742058X11000087

Strassle, P. D., Stewart, A. L., Quintero, S. M., Bonilla, J., Alhomsi, A., Santana-Ufret, V., Maldonado, A. I., Forde, A. T., & Nápoles, A. M. (2022). COVID-19-Related Discrimination Among Racial/Ethnic Minorities and Other Marginalized Communities in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 112(3), 453–466. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2021.306594

Sullivan, D., Landau, M., Rothschild, Z., & Keefer, L. (2014). Searching for the root of all evil: An existential-sociological perspective on political enemyship and scapegoating. In J. Prooijen & P. Lange (Eds.), Power, Politics, and Paranoia: Why People Are Suspicious of Their Leaders (pp. 292–311). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139565417.020

Sundararajan, L. (2020). Strong-ties and weak-ties rationalities: Toward an expanded network theory. Review of General Psychology, 24(2), 134–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/1089268020916438

Sundararajan, L., & Yeh, K. H. (2021). Strong ties and weak ties rationality: Theory and scale development. Integrative Psychological & Behavioral Science, 1–15. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12124-021-09645-5

Tan, C., & Umamaheswar, J. (2021). Structural racism and the experience of “tightness” during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2021.1959625

Thong, J. J-A., Ting, R.S.-K., Jobson, L., & Sundararajan, L. (2022). In the Wake of Religious Conversions: Differences in Cognition and Emotion across Three Religious Communities of a Hunter Gatherer Tribe in Malaysia. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/rel0000493

Ting, R. S.-K., & Sundararajan, L. (2018). Culture, cognition and emotion in China’s religious ethnic minorities: Voices of suffering Among the Yi. Palgrave Macmillan Publication.

Ting, R. S.-K., & Zhang, K. (2021). Giving voice to the voiceless: A peaceable research paradigm for psychology in China. In A. Dueck (Ed.), Indigenous psychology of spirituality (pp.73–96). Palgrave Studies in Indigenous Psychology. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-50869-2_4

Triandis, H. C. (1995). Individualism & collectivism. Westview Press.

Triandis, H. (2015). Collectivism and individualism: Cultural and psychological concerns. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 4, 206–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.24008-7

Tynes, B. M., Rose, C. A., & Williams, D. R. (2010). The development and validation of the online victimization scale for adolescents. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 4(2), article 2. https://cyberpsychology.eu/article/view/4237/3282

Vandrevala, T., Alidu, L., Hendy, J., Shafi, S., & Ala, A. (2022). ‘It’s possibly made us feel a little more alienated’: How people from ethnic minority communities conceptualise COVID-19 and its influence on engagement with testing. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 27(2), 141–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/13558196211054961

Wang, S., Chen, X., Li, Y., Luu, C., Yan, R., & Madrisotti, F. (2021). ‘I’m more afraid of racism than of the virus!’: Racism awareness and resistance among Chinese migrants and their descendants in France during the Covid-19 pandemic. European Societies, 23(sup1), S721–S742. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2020.1836384

Weiden, F., Levinsky, M., Schiff, M., Becker, N., Pat-Horenczyk, R., & Benbenishty, R. (2021). COVID-Related Concerns, the Need for Help, and Perceived Microaggression among Young Ultra-Orthodox Jewish Respondents in Israel. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6445. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126445

Williams, D. R., Yu, Y., Jackson, J. S., & Anderson, N. B. (1997). Racial Differences in Physical and Mental Health: Socio-economic Status, Stress and Discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology, 2(3), 335–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910539700200305

Wong, L. P., & Sam, I. (2011). Knowledge and attitudes in regard to pandemic Influenza A (H1N1) in a multiethnic community of Malaysia. International Journal of Behavioural Medicine, 18, 112–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-010-9114-9

Yang, L. H., Kleinman, A., Link, B. G., Phelan, J. C., Lee, S., & Good, B. (2007). Culture and stigma: Adding moral experience to stigma theory. Social Science & Medicine, 64(7), 1524–1535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.11.013

Yang, Q., Young, I. F., Wan, J., & Sullivan, D. (2021). Culturally Grounded Scapegoating in Response to Illness and the COVID-19 Pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 632641–632641. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.632641

Yeh, K. H., Sundararajan, L., Ting, R. S. K., Liu, C., Liu, T., & Zhang, K. (2022). A Cross Cultural study of Strong Ties and Weak Ties Rationalities: Toward an Ontological Turn in Psychology. The Humanistic Psychologist. https://doi.org/10.1037/hum0000284

Yu, Y. J., Park, Y. S., Keller, A., Noh, J. W., & Cha, J. A. (2021). Mixed-methods systematic review of the impacts of coronavirus on society and culture. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 491. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020491

Yuan, Y., Zhao, Y. J., Zhang, Q. E., Zhang, L., Cheung, T., Jackson, T., Jiang, G. Q., & Xiang, Y. T. (2021). COVID-19-related stigma and its sociodemographic correlates: A comparative study. Global Health, 17, 54. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-021-00705-4

Zong, X., Cheah, C. S. L., & Ren, H. (2021). Chinese American Adolescents’ Experiences of COVID-19-Related Racial Discrimination and Anxiety: Person-Centered and Intersectional Approaches. Journal of Research on Adolescence. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12696

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge and thank the following research assistants (Esther Ong, Jia Yee Choo, Keerthi Rajesh, Ling Yin Chan, Min Jun Choong, Darlene Koh Mei-Yi) from Monash Culture and Health Lab for their contribution during the abstract and full-text screening of the articles.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. The authors acknowledge Monash University School Collaborative Grant 2021 (Grant number: SED 0000–55) for their support and funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Systematic review conception and design: May Kyi Zay Hta, Rachel Sing-Kiat Ting; Abstract screening: May Kyi Zay Hta, Qian Hui Gan; Full-Text Screening: May Kyi Zay Hta, Qian Hui Gan, Rachel Sing-Kiat Ting, Pei Hwa Goh; Critical appraisal: May Kyi Zay Hta, Pei Hwa Goh, Rachel Sing-Kiat Ting; Analysis and interpretation through consensual approach: May Kyi Zay Hta, Rachel Sing-Kiat Ting, Liz Jones, Pei Hwa Goh, Qian Hui Gan; Manuscript writing and editing: May Kyi Zay Hta, Rachel Sing-Kiat Ting, Liz Jones, Pei Hwa Goh, Qian Hui Gan. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This study is a systematic review and did not require any ethical approvals as there were no human participants or animals involved.

Informed consent

Not applicable as no human participants were recruited.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zay Hta, M.K., Ting, R.SK., Goh, P.H. et al. A systematic review on the cultural factors associated with stigma during pandemics. Curr Psychol 43, 12938–12969 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04509-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04509-0