Abstract

Bullying is a serious problem around the world, especially among adolescents. Evidence exists that low levels of social perspective-taking as well as belief in a just world played an important role in bullying. Both dispositions function as psychological resources that may help students behave appropriately in social life. Previous research identified distinct bullying roles such as perpetrator, victim, assistant, reinforcer, defender, and bystander experiences. Although this participant-role approach has been extensively investigated in the last years, a simultaneous examination of students’ perspective-taking and belief in a just world in relation to their experiences in these roles is still missing. This study’s objective was to examine a differential approach of school students’ visuospatial and dispositional social perspective-taking, emotional concern, and personal belief in a just world in relation to their experiences in bullying roles. We tested these relations in a sample of n = 1309 adolescents (50.6% female, Mage = 13.73, SDage = 0.85) from 38 schools in Germany. The results from a latent structural-equation model suggested that experiences as a perpetrator, assistant, reinforcer but also as defender related to low visuospatial social perspective-taking. Emotional concern was positively related to defender experiences. Personal belief in a just world was negatively associated with experiences as a perpetrator and a victim. The results underline the importance of disentangling concurrent contributions of perspective-taking and belief in a just world related to the bullying roles. We conclude that adolescents’ visuospatial social perspective taking seems to be a further mental resource against antisocial behavior in bullying.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There is a global consensus that students’ school-related experiences in bullying processes threaten their health and learning achievement. In a bullying process, at least one perpetrator deliberately and repeatedly attacks a person to harm this victim by exploiting power imbalance (Olweus, 1994; Olweus et al., 2019; UNESCO, 2018). The socio-ecological diathesis-stress model of the emergence and persistence of bullying proposed by Swearer and Hymel (2015) provides approaches to explain bullying in terms of a complex group process. The model describes student’s dispositions, social contexts, and mental resources that are related to one another (Swearer & Hymel, 2015). One possible mental resource of adolescents might be social perspective taking (PT) that is seeing or imagining and understanding another person’s point of view. PT requires visuospatial social PT—the tendency to see and imagine other people’s perspectives (Piaget, 1928, 1952, 2008)—which is related to dispositional PT (Erle & Topolinski, 2015; Wolgast et al., 2019). Adolescents need to imagine others’ perspectives in order to make socially appropriate responses in group contexts (Wolgast et al., 2019). However, no findings are published on the relationships between students’ visuospatial social PT and each bullying role yet. An evident mental resource in bullying processes is the disposition PT (van Noorden et al., 2014; Wolgast et al., 2019). It is the tendency to understand what another person feels. This dispositional PT and emotional concern—the tendency to feel what another person feels—are well known dimensions of empathy (Davis, 1980, 1983). However, researchers (e.g., Swearer & Hymel, 2015) classified emotional concern in bullying processes as empathic anger, a negative emotional response to the stressors, and thus it cannot be a mental resource (Davis, 1980, 1983; van Noorden et al., 2014; Wolgast et al., 2019). Together with students’ personal belief in a just world (BJW, Donat et al., 2018)—the conviction that people deserve what they get and get what they deserve—these dispositions can help adolescents behave in socially appropriate ways.

In contrast, stressors such as bullying experiences threaten adolescents’ mental health and are negatively associated with mental resources. Additionally, deficits in dispositional PT, emotional concern, and personal BJW are related to frequent experiences in bullying processes and a high risk of antisocial behavior of children, adolescents, and adults (Gasser & Keller, 2009; van Noorden et al., 2014).

Researchers have largely focused on either selected indicators of assumed mental resources such as dispositional PT and related it to only some (Espelage et al., 2018; Thornberg & Wänström, 2018; van der Ploeg et al., 2017; van Noorden et al., 2017) roles in bullying processes (Salmivalli et al., 1996). However, visual-spatial social PT, dispositional PT, emotional concern, personal BJW, and bullying roles are concurrently related phenomena in school contexts. A simultaneous investigation of students’ engagement in visuospatial social PT, dispositional PT, emotional concern, and personal BJW in relation to experiences in the perpetrator, assistant, reinforcer, victim, defender, or bystander role (Salmivalli et al., 1996) would yield findings that extend previous research in that field (e.g., Donat et al., 2018; Gasser & Keller, 2009; van Noorden et al., 2014). Consequently, the aim of this study was to disentangle the relationships of adolescents’ visuospatial social PT, dispositional PT, emotional concern, and personal BJW to role experiences in bullying processes by visuospatial social PT tasks as well as self-report measures of empathy, personal BJW, and bullying experiences in an online-survey. We expected that the mental resources visuospatial social, dispositional PT, and personal BJW would have differential relations with different bullying role experiences. In the following sections, we provide a brief overview of existing theoretical approaches and empirical findings on both concepts of PT, emotional concern, personal BJW, and bullying processes before describing the current study.

Bullying and roles in the bullying process

School-related bullying is defined as a school-specific subtype of aggressive behavior in which a perpetrator intentionally harms another student by exploiting their superior strength and power (Olweus, 1993). By exploiting their superior power (= power imbalance), perpetrators repeatedly attack their victims for an extended period of time by using psychological and/or physical means. Previous research has indicated bullying perpetrators’ increased tendency to engage in delinquent behaviors (Olweus, 1994) and even significantly increased likelihood of presenting suicide ideation or making a suicide attempt in contrast to students without bullying perpetration experiences (Katsaras et al., 2018). Such experiences are also related to behavioral problems, difficulties in social and academic learning (Frick et al., 2014), frequent delinquency (Hasking, 2007), and criminal behavior (Frick et al., 2014). Perpetrators are often supported by their assistants (who support them to bully others) and bullying reinforcers (who exhibit positive reactions such as laughing, e.g., Rigby & Slee, 1993; Schäfer & Korn, 2004). Thus, not only perpetrators but also their assistants and reinforcers demonstrate antisocial behaviors when the perpetrator attacks the bullying victim. Antisocial behaviors are related to high risks of becoming a perpetrator, delinquent adult, difficulties in social and academic learning at later points of time (Frick et al., 2014; Olweus, 1994).

Adolescents’ bullying victimization experiences and mortality are discussed in light of social problems and withdrawal (Brunstein Klomek et al., 2010). Social exclusion seems to be a common form of bullying and is related to the victim’s experiencing emotions such as anger or anxiety (e.g., Bondü et al., 2016; Garnefski & Kraaij, 2018). Usually, one defender supports the victim and engages in strategies to ward off bullying attacks (Nickerson et al., 2015). Furthermore, bystanders passively observe or try to ignore bullying processes (Pouwels et al., 2018). Bystanders were at elevated risk for interpersonal sensitivity and substance abuse (Callaghan et al., 2019). Defenders need reinforcement to defend also other bullying victims at later points of time, keep, or even improve their prosocial behaviors and strategies to solve social conflicts. Prosocial behaviors represent competencies that might help adolescents (including all bullying roles) in dealing with myriads of other social situations over their life-span (Bondü et al., 2016; Malti & Perren, 2011). Bystanders who learned prosocial strategies to intervene in social conflict situations and react accordingly in bullying situations may affect other students’ sense of safety and even the school climate (Gini et al., 2008).

In sum, researchers have shown that dispositional PT and just-world beliefs can be mental resources with regard to bullying processes (Donat et al., 2018; Wolgast et al., 2019). On the other hand, researchers continue to strive to improve prevention and intervention programs by considering additional mental resources such as visuospatial social PT. Intervention and prevention programs might further profit from insights in findings on disentangled concurrent relationships of different and yet unconsidered mental resources, that is, adolescents’ visuospatial social PT, dispositional PT, emotional concern, and personal BJW to their role experiences in bullying processes. The different research areas of both PT concepts, personal BJW, and role experiences in bullying processes are briefly described next, before we connect them in an integrated model.

Perspective-taking, emotional concern, and bullying roles

Theoretical basics of perspective-taking and emotional concern

Pioneers of research on individual cognitive (Piaget, 1928, 1952, 2008) and social development (Mead, 1934) already postulated that individuals are a product of their social interactions. These interactions allow them to compare and evaluate differences between their own perspectives and those of others (Lewis & Brooks-Gunn, 1979; Piaget, 1928, 2008; Wolgast, 2018). Seeing and imagining what other people see is a basic feature requiring visuospatial social PT that is the cognitive capacity used to establish a mental representation (mentalization) of another person’s perspective in the current social situation (Gehlbach et al., 2012; Wolgast et al., 2019). Thus, visuospatial social PT seems to be an underlying process of the disposition PT (Wolgast et al., 2019).

Davis (1980, 1983, 2018) described PT as a disposition and trait within his multi-dimensional conceptualization of empathy that considers various situations including conflict situations. Two dimensions of his empathy concept are dispositional PT and emotional concern. These two dimensions are also known as cognitive and emotional empathy, respectively, and often subsumed into empathy more generally (van Noorden et al., 2014; Wolgast et al., 2019). The disposition or dispositional PT is the tendency to attempt to imagine other people’s perspectives, feelings, and circumstances across various contexts (Davis, 1980; Wolgast et al., 2019). Emotional concern is the tendency to attempt to feel what other people are feeling in their circumstances across various contexts. Both dimensions are usually measured using a standardized inventory (Davis, 1980; Wolgast et al., 2019). Emotional concern is positively correlated with dispositional PT at low to moderate levels and with self-reported distress as well (Davis, 1983; Wolgast et al., 2019). Emotional concern is also related to high distress levels assessed by high cortisol levels (Engert et al., 2014). Consequently, emotional concern cannot be a mental resource although high scores were related to motivation for defending or helping behavior and low scores to antisocial behavior (van Noorden et al., 2014; see also Espelage et al., 2018; Forsberg et al., 2014; Fredrick et al., 2020; Zych, Ttofi et al., 2019). It is therefore important to examine dispositional PT and emotional concern in the complex bullying processes in further research.

Some research findings showed statistical associations between visuospatial social PT and dispositional PT regarding human(-like) targets (e.g., Erle & Topolinski, 2015) as well as empathy and emotion regulation (Engen & Singer, 2013). Thus, both concepts help people understand others’ behavior (Davis, 1983; Erle & Topolinski, 2015) through mentalization and consequently helps them regulate their emotional responses (Engen & Singer, 2013). Further research findings show positive relations between spatial performance, dispositional PT, and emotional concern as well as an automatic mode of perception (Barreda-Angeles et al., 2020).

Visuospatial social PT is part of the conceptualization of dispositional PT because the attempt to imagine other people’s perspectives regards seeing and imagining (“visuo”) their perspectives in their environment (“-spatial PT”). For example, researchers described a direct positive effect of spatial presence on perspective taking and emotional concern in a 360° virtual environment (Barreda-Angeles et al., 2020). Further previous research suggested that the change of spatial perspective requires cognitive resources, thereby activating a simplified and automatic mode of perception (Gniewek et al., 2018). Visuospatial social PT negatively related to antisocial behavior (Zych, Ttofi et al., 2019) but positively to prosocial behavior (Wolgast et al., 2019). Therefore, it is valuable to investigate visuospatial social PT in relation to role experiences in bullying processes which include pro- and antisocial behavior from different perspectives.

There are other conceptual approaches (Gehlbach, 2004; Selman, 1981) which are not outlined here for reasons of space. The consensus view of the different approaches on PT is that it is a cognitive capacity that already children learn and use differently in different contexts (Baron-Cohen et al., 1985; Gehlbach, 2004; Selman, 1981; Wimmer & Perner, 1983).

Relations to bullying roles: Theoretically and empirically

Little is known about visuospatial social PT and its relations to bullying processes, in particular the different bullying roles identified by Salmivalli et al. (1996), although bullying processes are often observable. A student who observes bullying processes and performs visuospatial social PT might defend and help the bullying victim directly or indirectly (e.g., by informing the responsible teacher). However, a bullying assistant who performs visuospatial social PT towards the bullying perpetrator might know how to support the perpetrator. Performed visuospatial social PT in bystanders might trigger their helping behavior; if bystanders see themselves from the victim’s perspective and situation, they may feel emotional concern and motivation to help or defend the bullying victim (Zych, Ttofi et al., 2019). The bullying perpetrator and the bullying reinforcer might be very focused on the bullying situation according to the literature (e.g., Salmivalli et al., 1996; van Noorden et al., 2014) and probably do not perform visuospatial social PT at all.

Considering the known relations between visuospatial social PT and dispositional PT (Erle & Topolinski, 2015; Wolgast et al., 2019), visuospatial social PT might play a role in bullying processes and might be similarly related to low bullying perpetration, assisting, or reinforcement experiences as dispositional PT (Gini et al., 2007; Pozzoli et al., 2017; van Noorden et al., 2014; Zych, Ttofi et al., 2019). Consequently, the other bullying roles might be related to low (bystander) or moderate (defender, victim) levels of visuospatial and dispositional PT (Gini et al., 2007; Hektner & Swenson, 2011; Espelage et al., 2018) highlighted the importance of both dispositional PT and emotional concern in social interactions and socialization. They assumed that adolescents with low levels of dispositional PT and emotional concern have difficulties in socialization, that can increase their risk of bullying perpetration and victimization (Espelage et al., 2018). Several studies focused on relationships between empathy, either dispositional PT or emotional aspects, and experiences in different bullying roles (Zych, Ttofi et al., 2019). Defenders scored high on dispositional PT and emotional concern (Zych, Ttofi et al., 2019) but assistants and reinforcers scored low on empathy (Maeda, 2003). A not significantly low positive meta-effect was found between empathy and bystander intention to intervene in a meta-analysis (Polanin et al., 2012), although previous research disclosed significantly low positive effects (Stevens et al., 2000). These studies highlighted the multidimensional nature as well as differential psychological functioning of empathy and in particular its complex relations to bullying perpetration or victimization as key points that should be acknowledged in the development of future prevention or intervention programs (van Noorden et al., 2014).

An important finding is that children or adolescents with bullying victimization experiences seem to be able to feel what others feel while having difficulties understanding others’ feelings (van Noorden et al., 2014). This deficiency in dispositional PT makes adolescents vulnerable to victimization; in contrast, as strong visuospatial and dispositional PT improves the quality of interpersonal relationships (Wolgast et al., 2019) and buffers against victimization.

Dispositional PT is already a component of preventive interventions (Garandeau et al., 2016; Zych, Baldry et al., 2019; Zych, Ttofi et al., 2019) and seems to be a mental resource in bullying processes.

However, direct relations of visuospatial social PT, dispositional PT, emotional concern, and personal BJW with bullying role experiences have not yet been examined in previous research.

Belief in a just world and bullying

Theoretical basics of belief in a just world

Just-world research is a line of research that focuses on another mental resource in social situations, namely the belief in a just world (BJW). This belief gives people confidence that the world is a stable and orderly place. According to the just-world hypothesis (Lerner, 1980), BJW refers to people’s need to believe in a just world in which everyone gets what they deserve and deserves what they get. Researchers have shown that two dimensions of BJW should be distinguished: The general BJW represents people’s conviction that the whole world is a just place; the personal BJW refers to people’s conviction that they are usually treated justly themselves (Dalbert, 1999). In the current study, we focused on the personal BJW due to several theoretical reasons. Most importantly, just-world researchers have argued that personal BJW is a better indicator of the justice motive and a better predictor of adaptive outcomes such as appropriate social behavior (helping, avoiding aggression) and well-being, especially among school students (Correia & Dalbert, 2008; Dalbert & Donat, 2015; Hafer & Sutton, 2016). As we aimed to investigate students’ experiences with bullying behavior, it seems that their personal BJW might be a more important psychological resource than their general BJW. .

Accordingly, findings from just-world research support the idea that personal BJW represents a significant psychological resource that serves important adaptive functions. When people are confronted with injustice and adverse circumstances, the assimilation function of personal BJW (Dalbert, 2001; see Dalbert & Donat, 2015 for a review) helps them preserve personal BJW and mental health by restoring justice psychologically, for example, by minimizing or denying the injustice (Lipkus & Siegler, 1993), avoiding self-focused rumination (Dalbert, 1997), or forgiving (Strelan, 2007). According to the motive function (Dalbert, 2001; Dalbert & Donat, 2015), people with a strong BJW are motivated to strive for justice for its own sake and maintain a just world by achieving personal goals by just means. The BJW involves a personal contract and the obligation to behave justly, and strong just-world believers are confident that such behavior will be justly rewarded in the future. Thus, personal BJW helps people avoid unjust and rule-breaking or even antisocial behavior such as bullying.

Empirical relations to bullying roles

Students with high levels of personal BJW were better able to cope with negative emotions (e.g., anger, Dalbert, 2002), and with school distress and depressive symptoms (Kamble & Dalbert, 2012), than students with low personal BJW levels. Previous research demonstrated these relations in victims and in non-victims (Donat et al., 2016). Accordingly, students with a strong personal BJW would minimize or deny such experiences, or even forgive those who harmed them. In turn, personal BJW might help students mentally cope with experiences of victimization (Donat et al., 2020). Just-world research has further shown that students’ personal BJW is negatively related to bullying perpetration and other forms of deviant behavior (Donat et al., 2018, 2020). In line with just world theory, it can be assumed that students with a strong personal BJW would also avoid acting as assistants and reinforcers in the bullying process. However, these relations have not been investigated yet. Furthermore, strong just-world believers were more likely to help people in need (Bierhoff et al., 1991) and personal BJW has also been shown to be positively related to social responsibility (Bierhoff, 1994) and prosocial behavior in adolescents (Caroli & Sagone, 2014). Thus, the personal BJW should encourage students to help victims in bullying situations. However, to our knowledge, only one study investigated bullying defender behavior in connection with personal BJW (Correia & Dalbert, 2008), and the relation was insignificant. There is no study in which bystanders’ behavior was related to personal BJW.

A Social-Ecological diathesis–stress model: Focusing on perspective-taking and belief in a just world

Social processes in school may involve prosocial behavior (e.g., a student defends another student) and anti-social behavior (e.g., a student attacks another student, Salmivalli et al., 1996). Swearer and Hymel (2015) suggested “that effective bullying prevention and intervention efforts must take into account the complexities of the human experience, addressing both individual characteristics and history of involvement in bullying, risk and protective factors, and the contexts in which bullying occurs, in order to promote healthier social relationships” (Swearer & Hymel, 2015, p. 344). They reviewed research findings on experiences in bullying processes and proposed a Social-Ecological Diathesis–Stress Model (Swearer & Hymel, 2015). This model involves contributing variables in the dynamic of bullying processes. Examples are perpetrators’ social integration or marginalization, and victimized students’ social avoidance (Swearer & Hymel, 2015). The model describes relationships between biological, psychological, and social factors including stressors such as bullying experiences (Swearer & Hymel, 2015) that influence an individual’s health. The aim of our study was to investigate and adapt a part of this model which includes relations between sex (biological), both concepts of PT, emotional concern, and personal BJW (psychological) as well as bullying experiences in different roles (social stressors; Kaltiala-Heino et al., 2000; Katsaras et al., 2018; Swearer & Hymel, 2015).

There are some overlaps between the Social-Ecological Diathesis–Stress Model (Swearer & Hymel, 2015) and the framework of empathy based on an inclusive definition (Davis, 2018). Briefly, the framework of empathy summarizes biological, personal, and situational factors involved in processes that determine helping, aggression (e.g., bullying), or other forms of social behavior.

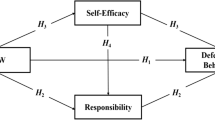

We adapted both theoretical models to the current study by replacing broad terms with specific variables related to individual demographics (e.g., gender, age, electronic device available), visuospatial social PT, dispositions, and role experiences within bullying processes on the social-behavior dimensions of “aggression” and “helping”. Finally, we only included relations that we aimed to examine. Figure 1 gives an overview of the adapted integrated model used in the current study. We included the adolescent’s biological (sex, age) and sociocultural background (ethnicity, electronic device) that was related to their visuospatial and dispositional PT, personal BJW, or bullying experiences in previous research as outlined next.

Adolescent’s biological and sociocultural background. In their systematic review of 40 empathy studies, van Noorden et al. (2014) cited a range of small-to-moderate effect sizes between dispositional PT and bullying experiences that were age group-specific (e.g., for young adolescents aged 11 to 13). Sex consistently determined both empathy dimensions and experiences in bullying processes separately at low levels (van Noorden et al., 2014) as well as ethnical background (Fousiani et al., 2019; Strohmeier et al., 2008).

The relationships between individual psychological dispositions and social processes including experiences in bullying processes might depend on culture and context (Swearer & Hymel, 2015). Thus, adolescent’s ethnic background should be considered in the current study. Family- and peer-group-specific habits and practices as (social) media use including electronic devices (e.g., Bjereld et al., 2017) are related to adolescents’ social life at school due to talking about appropriate electronic devices with classmates who even may expect a certain electronic device. A student who is not able to talk about electronic devices due to missing experiences with it might be at risk of social exclusion (Bjereld et al., 2017).

In summary, previous research on dispositional PT, emotional concern, and personal BJW suggests that they are differentially related to bullying processes (e.g., van Noorden et al., 2014). However, there is scant evidence on whether adolescents’ visuospatial PT, dispositional PT, emotional concern, and personal BJW concurrently relate to their experiences in different bullying roles (i.e., perpetrator, assistant, reinforcer, victim, defender, bystander, Salmivalli et al., 1996). Drawing upon the Social-Ecological Diathesis-Stress Model (Swearer & Hymel, 2015) and the model of empathy (Davis, 2018), we aimed to examine whether visuospatial social PT relates to experiences with different bullying roles, as well as whether dispositional PT, emotional concern, and personal BJW concurrently relate to these experiences. This integrated model contributes to the understanding of relations between mental resources (e.g., both concepts of PT, personal BJW), and experiences in bullying processes, especially, whether these relations are different from each other when concurrently analyzed. Testing these concurrent relations provides findings for further approaches on how to consider bullying roles in preventive intervention programs differently. An additional strength of our study is that we aim to provide important evidence for the differential validity of the different PT concepts with regard to bullying experiences. To our knowledge, no previously published study has simultaneously regarded these relations including PT engagement tasks and self-report measures in one model.

The current study

In this study, we expected disentangled different relationships between the three mental resources visuospatial PT, dispositional PT, personal BJW, and role experiences in bullying processes when simultaneously examined in one SEM. In previous research, dispositions (dispositional PT, personal BJW) significantly explained a considerable amount of variance in bullying experiences (e.g., Donat et al., 2012). We therefore expected that visuospatial social PT would explain an amount of variance in role experiences with bullying processes when included in a single SEM with dispositional PT, emotional concern, and personal BJW.

In accordance with Salmivalli et al. (1996), we considered bullying role experiences as perpetrator, assistant, reinforcer, victim, defender, and bystander. Our hypotheses with regard to examining the relations in one SEM were as follows: (1) Students’ visuospatial social PT performance is related to their self-reported experiences in each bullying role (negatively to perpetration, reinforcement, assistance, bystanding, and victimization experiences; positively to defending experiences) when including the control variables gender, age, mother tongue (as proxy for ethnical background), and electronic device used in this study. (2) Dispositional PT, emotional concern, and personal BJW are significantly related to experiences in different bullying roles (negatively to perpetration, reinforcing, assistance, bystanding, and victimization experiences; positively to defending experiences), again when controlling for gender, age, mother tongue (as proxy for ethnical background), and electronic device used in this study.

In the sections below, we detail the method we used to determine the sample size needed to disclose effects using SEM. Afterwards, all measures used in the analyses are presented. We stopped data collection before we began analyzing the data.

Method

Planned sample size

As mentioned above, van Noorden et al. (2014, p. 641) cited a range of small-to-moderate effect sizes (rmin = –0.09, rmax = –0.52) between dispositional PT and bullying experiences that were age group-specific (e.g., r = –.13 for young adolescents aged 11 to 13). We chose our sample size based on power analyses incorporating these effect sizes from previous research (van Noorden et al., 2014). The power analyses indicated that at least n = 250 participants were needed to identify the model structure and n = 876 to uncover effects (number of latent factors = 10, indicators = 63, r = 0.15, significance level = 0.05, power = 0.80) using SEM (Soper, 2020).

Sample

Our sample consisted of 1313 adolescents in 38 schools. These students volunteered to participate in the study (50.6% female, 6.0% missing values on the gender variable, Mage = 13.73, SDage = 0.85). The majority (n = 881) of the students attended academic-track classes (Gymnasialklassen) and n = 393 vocational school track classes (Realschulklassen; 3.0% missing values out of 1313 cases for the school type variable). The following responses were recorded concerning the students’ mother tongue(s): 85.0% German, 5.1% German and another language (bilingual), 2.9% an Indo-European language (e.g., Russian), 4.0% other languages, 3.0% missing values. We then detected four cases with implausible response patterns. Ultimately, data from n = 1309 adolescents were available for analysis, which was sufficiently large given our power analysis targets.

Procedure

Approval by the state school authority. Our study received approval from the school authority in the state in which it was conducted: First, we sent a research proposal for an online survey on the interplay between adolescents’ traits and behavior at schools to the state school authority for approval. The school authority approved our research proposal. Then, we and undergraduate teacher education students contacted school principals or teachers of the state to invite them and their students to participate in a study about seeing what other people see. We followed up with a second call about two weeks after the initial inquiry. We offered them to provide aggregate results of the study at the school level as an incentive for participation. Once a principal provided approval at the school level, the teacher education students made an appointment with the class teacher to conduct the online survey with the students in their class. This ensured that the online survey was conducted under controlled conditions. Informed consent was obtained from the parents. Students who volunteered to participate clicked on the survey URL in class. The first screen explained the anonymous and volunteer nature of the study and instructed them to click to continue on to the first task, the three-buildings task described below.

Measures

All measures and questions were administered online and in German using the standard back-translation process for materials not already available in German. Measures were presented in the following order: first, the three-building task (Shelton et al., 2012), a variant of the classic Piagetian three-mountains task adapted for student samples (see three studies in Wolgast & Oyserman, 2019); second, dispositional PT and emotional concern items (Davis, 1980) as well as personal BJW items (Dalbert, 1999); third, bullying roles (Rigby & Slee, 1993; Salmivalli et al., 1996; Schäfer & Korn, 2004). The share of missing values on these measures ranged from 0.0 to 2.3%.

We used McDonald’s ω (see Dunn et al., 2014, for advantages over Cronbach’s α), instead of Cronbach’s α, to estimate the internal consistency since it is a point estimate that makes few and realistic assumptions: It requires congeneric variables rather than τ-equivalent variables (Dunn et al., 2014; Hayes et al., 2020; Revelle & Zinbarg, 2008; Zinbarg, 2006). Inflation and attenuation of internal consistency estimation are less likely (Dunn et al., 2014). McDonald’s ω can be calculated within the R environment using the R package psych (R Development Core Team, 2009; Revelle, 2019) and interpreted by the same levels as Cronbach’s α (Schweizer, 2011). Note the increasing number of articles about the advantages of McDonald’s ω over Cronbach’s α (Dunn et al., 2014; Hayes et al., 2020; Revelle & Zinbarg, 2008; Zinbarg, 2006). We provide the full set of instructions and the items used for the measure “Experiences in a bullying role” in the Supplementary Information 1a.

Visuospatial perspective-taking test

Three-buildings task. Based on the Piagetian three-mountains task and prior work by Shelton and colleagues (2012), Wolgast and Oyserman constructed buildings from Lego bricks and placed seven toy targets (as observers) on numbered pedestals around three buildings on a round platform at 45° intervals and took photographs of each of the vantage points. They used these numbers to mark the seven targets. As in the study by Shelton and colleagues, the toy targets varied so that for the first three buildings the targets were blocks, and for the second three buildings the targets were animals. Wolgast and Oyserman (2019) showed participants their own view of each building (straight on at 0°) and then a second photograph taken from the perspective of one of the seven toy targets (or 0° again) and asked participants whose perspective they were seeing. Specifically, one’s own perspective was straight on at 0° (me), target (#1) was placed at 45°, target (#2) at 90°, target (#3) at 135°, target (#4) at 180°, target (#5) at 225°, target (#6) at 270°, and target (#7) at 315° (Wolgast & Oyserman, 2019). The Supplementary Information 2 online shows the three-buildings task used in the current study.

First, participants completed a practice trial. Then, they completed the eight task trials two times each (once using blocks as observers, once using animal toys). The 16 trials yielded satisfactorily reliable PT scores, with McDonald’s ω = 0.90 computed within the R environment (R Development Core Team, 2009). The order of trial presentation was randomized, each position was presented once, and response time was not limited. Performance was measured using the mean accuracy of responses (each correct response was coded ‘1’, each missing or incorrect response was coded ‘0’, following suggestions for coding this kind of data, Lee & Ying, 2015).

Trait measures Footnote 1

Before presenting the trait measures, the participants received instructions encouraging them to think about how they usually act in different situations (see Supplementary Information 1b). The adolescents rated their responses on each of the trait measures on a 6-point scale (from 1 = not true at all to 6 = absolutely true).

Dispositional PT (adapted to adolescents; Davis, 1980) was assessed using adolescents’ responses to five statements, such as: I sometimes try to understand my friends better by imagining how things look from their perspective. Scoring high on the dispositional PT measure indicates that a person tends “to anticipate the behavior and reaction of others” (Davis, 1983, p. 115) with regard to their friends. McDonald’s omega was ω = 0.73, suggesting an acceptable degree of reliability, and served as a predictor variable for testing the relations with experiences with bullying roles.

Emotional concern (Davis, 1980, p. 8) was measured with responses to five statements: I am often quite touched by things that I see happen; Emotional concern served as a further predictor variable (ω = 0.71) in our statistical analyses.

BJW was assessed with the seven-item Personal BJW Scale (Dalbert, 1999), for example: Overall, events in my life are just. BJW served as a fourth predictor variable (ω = 0.88) in the data analyses.

Demographic background. Previous research uncovered, as mentioned in Sect. 5, predictive effects of age (van Noorden et al., 2014), gender, ethnical background (Fousiani et al., 2019), and electronic device (Bjereld et al., 2017) that the adolescents used to participate in the online survey were included. We therefore included these variables in our single SEM.

Experiences in bullying processes

Experiences in a bullying role (Rigby & Slee, 1993; Salmivalli et al., 1996; Schäfer & Korn, 2004) was introduced by a set of instructions to ensure that adolescents had similar understandings of the phenomenon bullying at school. Thus, we used a definition-based measure of bullying experiences (Smith, 2014). Then, the adolescents were asked how often they had experienced different bullying situations in the last four weeks in a set of 30 items (five items each for experiences in each role). Each item started with the same phrase (How often in the last four weeks…). Example items include: …did you make other adolescents scared? (perpetrator, ω = 0.73); …did other students make fun of you? (victim, ω = 0.86); …did you help the perpetrator to bully? (assistant, ω = 0.80); …did you giggle or laugh when someone was bullied? (reinforcer, ω = 0.82); …did you comfort the victim? (defender, ω = 0.80); …did you ignore someone being bullied? (bystander, ω = 0.75). For reasons of space, further details are presented in the Supplementary Information 1a.

Statistical analyses

In accordance with our hypotheses, we evaluated a confirmatory ten-factor model including the latent factors visuospatial social PT, dispositional PT, emotional concern, personal BJW, and experiences in the six bullying roles using the R package lavaan (Rosseel et al., 2018). The term “latent” refers to factors which are not observable. The advantage of measuring factors and their concurrent relationships at a latent level is that measurement errors have been separated out. For example, the five items concerning victimization experiences (indicators) were used to measure the unobservable construct victimization experiences (latent factor) and account for measurement error. The items for the aforementioned constructs were used as indicators measuring the ten latent factors. The constructs were measured in this way to identify each assumed latent factor stripped of measurement error (see Supplementary Information 3a for the statistical CFA model).

Measurement invariance across gender in a CFA is a prerequisite for SEM including data from both female and male participants. With regard to cut-off values, we followed Rutkowski and Svetina’s (2014) cut-off value recommendations and agreed prior to analysis to consider the hypothesis of scalar invariance for mean comparisons to be supported when ΔCFI < 0.020 and ΔRMSEA < 0.010.

We then expanded the CFA model into a single SEM to measure the relations between the ten latent factors visuospatial social PT, dispositional PT, emotional concern, personal BJW, and experiences in each of six bullying roles simultaneously. The control variables gender, age, mother tongue, and medium represented by the electronic device that the adolescents used to participate in the online survey were also included (see Supplementary Information 3b for the statistical SEM). Each of the ten latent factors was regressed on the control variables. The results are depicted in graphical form in Fig. 2 (without statistical modeling, e.g., indicators and error terms, for reasons of space). The CFA and SEM were constructed with the R package lavaan, all variables were z-standardized, weighted least squares means and variance-adjusted estimation were applied (WLSMV estimation; Rosseel, 2018), and adjustments for complex data were carried out (equivalent to TYPE = COMPLEX in MPlus; Oberski, 2015) to control for the nested character of the data.

Results

Correlation coefficients among the ten factors are depicted in Supplementary Information 4a. The CFA suggested a good fit between the ten-factor model and the data: χ2(1845) = 127.867, p = 1.000, comparative fit index (CFI) = 1.000, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.001, CI [< 0.001, < 0.001], standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = 0.047 (see Supplementary Information 4b for CFA results). Measurement invariance across gender was tested in a multi-group analysis using this ten-factor CFA model and supported the assumption of metric invariance (ΔCFI = 0.01 and ΔRMSEA < 0.01, Svetina & Rutkowski, 2014). Further results from invariance testing are not presented here for reasons of space but can be obtained from the corresponding author.

The SEM also suggested a good fit between our ten-factor model including the manifest predictor variables and the data: χ2(2073) = 3892.660, CFI = 0.950, RMSEA = 0.026, CI [0.025, 0.028], SRMR = 0.047 (see Supplementary Information 3a and 3b). Supplementary Information 5 provides detailed information on the path coefficients and standard errors of the data. Results regarding our hypotheses are detailed in the next sections.

The dispositional PT factor was weakly positively associated with experiences as a defender only (see SEM part 2e in Fig. 2, p < .05), while emotional concern was positively associated with experiences as a victim and defender (p < .05). The results in Fig. 2a–c show moderate negative relations between emotional concern and experiences as a perpetrator (2a), assistant (2b), and reinforcer (2c, p < .05), but no significant relations between dispositional PT and these experiences.

Personal BJW was negatively associated with experiences as a perpetrator (see the SEM parts 2a and 2d in Fig. 2, p < .05) and as a victim, the latter even at a moderate level, but was not significantly associated with experiences as an assistant or reinforcer. Personal BJW was negatively related to experiences as a defender (2e, p < .05). There were no significant relations between visuospatial social PT, dispositional PT, or personal BJW to experiences as a bystander (see Fig. 2a–e).

Moreover, there were significant, small effects of adolescents’ sex (i.e., boys scored higher than girls) on their experiences in bullying perpetration (β = 0.24), assistance (β = 0.25), reinforcement (β = 0.23), and as bystander (β = 0.07). Only the significant, small effect of sex on experiences in bullying defending existed with an advantage for girls (β = − 0.09). Standard errors and 95% confidence intervals are not presented here for reasons of space (see Supplementary Information 5 for these details). The proportion of explained variance in the six latent outcome factors were as follows: experiences as bullying perpetrator R2 = 0.26, victim R2 = 0.15, assistant R2 = 0.20, reinforcer R2 = 0.23, defender R2 = 0.16, and bystander R2 = 0.06.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to disentangle the relationships between adolescents’ visuospatial social PT, dispositional PT, emotional concern, personal BJW, and experiences in bullying processes based on the social-ecological diathesis-stress model (Swearer & Hymel, 2015) and the model of empathy (Davis, 2018). We aimed to disentangle the degree of overlap and distinctiveness in both concepts of PT and personal BJW among groups of adolescents who reported experiences in different bullying roles (i.e., perpetrator, assistant, reinforcer, victim, defender, bystander). Each of the ten latent factors visuospatial social PT, dispositional PT, emotional concern, personal BJW, and the bullying roles was represented as one criterion variable in a single structural equation model including relevant background variables according to the correlational study design.

Our research question was: Do concurrent relations exist between PT, emotional concern, personal BJW, and role experiences in bullying processes? We assumed that the mental resources PT and personal BJW would have differential relations with different bullying role experiences. Emotional concern (the emotional dimension of empathy) was included, although Swearer and Hymel (2015) classified it as empathic anger, because it was negatively related to bullying perpetration in previous research (van Noorden et al., 2014). Our hypotheses concerned the relations between adolescents’ visuospatial social PT, dispositional PT, emotional concern, personal BJW, and self-reported experiences in each bullying role (i.e., perpetrator, assistant, reinforcer, victim, defender, bystander). The results supported our hypotheses in part as discussed next.

Perspective-taking and emotional concern: Relations to bullying roles

The first hypothesis was: (1) Students’ visuospatial social PT is related to their self-reported experiences in each bullying role (negatively to perpetration, reinforcing, assistance, bystanding, and victimization experiences; positively to defending experiences) when including the control variables gender, age, mother tongue (as proxy for ethnical background), and electronic device used in this study. The electronic device was included due to findings from other studies that suggested a relatively high risk of bullying victimization experiences (e.g., social exclusion, see Sect. 5 of this paper for details) for those students who did not have an electronic device (Bjereld et al., 2017). Our results suggested with regard to Hypothesis (1) that adolescents with significantly lower levels of visuospatial social PT had more bullying experiences as a perpetrator, assistant, reinforcer, or even defender than those with higher levels of this PT concept. We can only speculate that visuospatial social PT among defenders depends more on the bullying situation than it does among others. Our three-buildings tasks did not present cues to trigger defending behavior in a bullying situation or another conflict situation. The results further support existing understandings of visuospatial social PT as a cognitive capacity that is used differently between and within students (Lewis & Brooks-Gunn, 1979; Piaget, 2008).

The second hypothesis was: (2) Dispositional PT, emotional concern, and personal BJW are significantly related to experiences in different bullying roles (negatively to perpetration, reinforcing, assistance, bystanding, and victimization experiences; positively to defending experiences), again when controlling for gender, age, mother tongue (as proxy for ethnical background), and electronic device used in this study. The dispositional PT measure did involve cues for conflict situations (Davis, 1980), and adolescents with significantly more likely dispositional PT actually reported more bullying defender experiences than students with less likely dispositional PT. The concurrently assessed emotional concern might give hints to explain this finding as outlined in the next subsection. Moreover, moral reasoning (Hoffman, 2001), social desirability, or imagining oneself in the situation of the victim rather than imagining the victim’s perspective might interact with responses to dispositional PT items.

Less likely emotional concern was related to more likely bullying perpetrator, assistant, or reinforcer experiences. Students with more likely emotional concern reported more bullying victimization or defending experiences than adolescents with less emotional concern. Van Noorden et al. (2014) already concluded in their systematic review that students with more emotional concern also more victimization experiences reported than those with less emotional concern. The result that emotional concern explained bullying defender experiences suggests a possibly related distress level that might motivate students to defend a bullying victim.

Belief in a just world: Relations to bullying roles

Personal BJW was significantly negatively related to perpetrator and victimization experiences, in line with previous research (e.g., Donat et al., 2018; Donat et al., 2018). Thus, students who endorsed personal BJW were less likely to self-report perpetration or victimization experiences. This result supports again the idea that personal BJW is an important mental resource for burdened people and for victimized students in particular (Donat et al., 2018).

Personal BJW did not explain assistant, reinforcer or bystander experiences, in contrast to theoretical expectations described in Sect. 4. Moderating or mediating factors (self-efficacy, school justice experiences) might play a role in the complex concurrent relations the current results demonstrated.

The somewhat unexpected negative relationship between personal BJW and bullying defender experiences might be explained by the so-called justice paradox (Peter et al., 2013), in which personal BJW can trigger victim-blaming among observers instead of active helping behavior to restore justice. It might also be possible that students with a strong personal BJW who witness bullying episodes, are more likely to assimilate such incidents instead of helping, for example, by denying or minimizing its injustice because they are not convinced to be able to effectively support the victim by active helping. The students’ self-efficacy might interact with personal BJW in such cases (Correia et al., 2016; Dalbert & Donat, 2015). Thus, personal BJW seems to not always be adaptive and does not necessarily contribute to just behavior, especially in bullying situations. Findings in other studies were inconsistent, with no relation (e.g., Correia & Dalbert, 2008) to positive relations (e.g., Bierhoff et al., 1991; Caroli & Sagone, 2014) between personal BJW and prosocial behavior.

We tested our hypotheses with a single SEM controlling for gender, age, mother tongue (as proxy for ethnical background), and electronic device. These covariates were included in this single SEM. We did not formulate assumptions about the covariates’ effects on the latently measured experiences in bullying roles since we used the covariates just for controlling explained variances in the latent measured bullying roles. Despite of that, differences between girls and boys are remarkable: Adolescents’ sex significantly predicted experiences in bullying roles except victimization or bystander experiences in bullying processes. Boys indicated more experiences in the bullying roles perpetrator, assistant, reinforcer, and bystander than girls, while girls indicated more experiences in the bullying role defender than boys. This additional finding underlines: Boys need more opportunities for social learning and role models for prosocial strategies to lower the risk of the introduced negative consequences (e.g., difficulties in social and academic learning, delinquent behaviors, substance abuse).

Conclusions for social-ecological diathesis–stress relations between cognitive capacity, dispositions, experiences in bullying processes and further research

Our study was the first to simultaneously investigate visuospatial social PT, dispositional PT, emotional concern, and personal BJW in relation to experiences in all six bullying roles identified by Salmivalli et al. (1996). The results support in part the integrated and adapted model on diathesis, dispositions and stressful bullying role experiences (see Fig. 1) based on the Social-Ecological Diathesis-Stress Model (Swearer & Hymel, 2015) and the model of empathy (Davis, 2018). In particular, the results highlight the necessity to consider differential relationships between adolescents’ dispositions, cognitive capacity, and each of the bullying roles.

Transversal (cross-sectional) studies on both concepts of PT, mentalization and relations with behavior regulation would provide new insights into the underlying processes of bullying experiences. Longitudinal studies including adolescents’ engagement in social PT tasks would deliver detailed insights into changes over time in experiences with different bullying roles.

Furthermore, we used visuospatial social PT tasks combined with self-report measures that clearly differentiate between the cognitive and emotional dimensions of empathy to examine concurrent relations to bullying roles according to the socio-ecological diathesis-stress model of bullying (Swearer & Hymel, 2015).

The results suggest that the measures we used assess visuospatial social PT and dispositional PT as different concepts with differential relevance for the bullying experiences of adolescents. Thus, the visuospatial social PT tasks (Wolgast & Oyserman, 2019) assess another concept than the dispositional PT measure based on Davis (1980).

The visuospatial social PT tasks just present a simulated group of observers around three buildings without any conflict situation. The dispositional PT measure includes cues to conflict situations in general. Responses on the visuospatial social PT tasks might be therefore negatively related to antisocial bullying experiences but not positively to bullying defender experiences. The positive relation between dispositional PT and bullying defender experiences supports previous studies (e.g., Wolgast et al., 2019; Zych, Ttofi et al., 2019) which showed that dispositional PT was negatively related to antisocial behavior but positively with prosocial behavior.

It would be valuable to assess visuo-spatial social PT using tasks adapted to a bullying situation, for example, including a simulated bullying situation instead of three buildings and simulated people around this conflict situation. Further studies might transfer this correlational design to cyberbullying, taking into account previous research in this area (Donat et al., 2020; Zych, Baldry et al., 2019).

Visuospatial social PT appears to be a further mental resource and an underexplored line of research related to bullying processes. For example, we did not find any research results on whether adolescents with bullying experiences use visuospatial social PT to see and understand what their peers see. This form of social PT theoretically serves as a foundation of later appraisals in various classroom situations. Interventions to increase social PT have the potential to regulate automatic emotional empathic responses (Engen & Singer, 2013; Wolgast et al., 2019) and reduce the likelihood of bullying processes. Future intervention studies with adolescents in this area might include visuospatial social PT.

Limitations

Our study has a number of limitations. First, it took place in Germany only. Future research in other countries is needed to test for generalizability. Second, we did not ask adolescents about their experiences with bullying processes in general. Thus, different bullying role experiences over time cannot be determined from the relatively short time frame referred to in the bullying measure (four weeks). Third, we also assessed personal distress and social desirability but psychometric analyses suggested low degrees of reliability in the corresponding data such that we did not use them in further analyses (see https://opendata.uni-halle.de//handle/1981185920/33768, http://dx.doi.org/10.25673/33571 for the scale documentation). Psychometricians frequently discuss the weakness of self-report measures because of the possibly included social desired response bias (Fraley et al., 2000). Social desired response behavior is however almost impossible when responding on tasks. Consequently, the responses on the visuospatial social PT tasks increase the degree of validity of the responses on the self-report measure ‘dispositional PT’ in our SEM. Another further process that also might play a role is the students’ possibly low test-taking motivation (Ranger & Kuhn, 2017; Wolgast et al., 2020) in the three-buildings task, because it was not personally important for the volunteers to score high in this task.

Furthermore, we focused on personal BJW in our study and did not consider potential relations of general BJW to bullying experiences due to several theoretical reasons. However, some of the expected relations of personal BJW to bullying roles (assistant, reinforcer, bystander) were non-significant or even reversed (defender). Here, it might be possible that general BJW would explain these experiences better than personal BJW because it predicted harsh social attitudes and was associated with victim-blaming and other defensive mechanisms in previous research (see Donat & Dalbert, 2015; Hafer & Sutton, 2016 for a review); such attitudes and mechanisms are likely to occur among bullying assistants, reinforcers, or bystanders. Additionally, considering general BJW in future research might also be fruitful because researchers have shown that both BJW dimensions form a common latent factor ‘BJW’ but each dimension may also contribute uniquely to adaptive psychological outcomes.

Implications for future research and practice

The markedly varying relations between the cognitive capacity visuospatial social PT, the dispositions PT, emotional concern, or personal BJW, and the bullying role experiences suggest the deployment of fine-grained prevention and intervention strategies that take these role experience-specific relationships with both concepts of PT, emotional concern, and BJW into consideration. Visuospatial social PT, emotional concern, and BJW might help students avoid perpetrator behavior, while only emotional concern might help them avoid assistant behavior. Visuospatial social PT and emotional concern might help them avoid reinforcer behavior. Bystanders seem to need other dispositional and situational factors that may activate them and lower their passivity (Fredrick et al., 2020; Polanin et al., 2012). Recent research (Fredrick et al., 2020) on bullying described that bystanders most likely intervene when they “notice bullying events, interpret as an event requiring intervention, accept responsibility for intervening, know how to intervene, and act” (Fredrick et al., 2020, p. 31). Each of these steps can be influenced by several precursors (Fredrick et al., 2020) that were out of the current study’s scope. Defenders are already equipped with empathy (i.e., dispositional PT and emotional concern), but have less personal BJW, and would benefit from strong visuospatial social PT. The latter can be improved by training (Meyer & Lieberman, 2016).

An increasing number of studies have demonstrated intervention effects on visuospatial social PT (e.g., Meyer & Lieberman, 2016), and in turn, the importance of dispositional PT for reappraisals of (conflict) situations and emotion regulation (Engen & Singer, 2013). Thus, positive relations to visuospatial social PT and dispositional PT might help adolescents consider other student’s points of view, behave in socially appropriately or even prosocial ways and avoid bullying experiences.

Data availability

Code availability

The R-code for the CFA is provided in Supplement 4b. Further R codes used for this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.

Notes

we used two further measures (personal distress, social desirability). However, the items did not form internally consistent scales (distress ω = 0.56, social desirability ω = 0.51), so we excluded them from the data analyses

References

Baron-Cohen, S., Leslie, A. M., & Frith, U. (1985). Does the autistic child have a “theory of mind” ? Cognition, 21(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0277(85)90022-8

Barreda-Angeles, M., Aleix-Guillaume, S., & Pereda-Banos, A. (2020). An ‘“Empathy Machine”’ or a ‘“Just-for-the-Fun-of-It”’ Machine? Effects of immersion in nonfiction 360-video stories on empathy and enjoyment. Cyberpsychology Behavior and Social Networking, 23(10), 683–688. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2019.0665

Bierhoff, H. W. (1994). Verantwortung und altruistische Persönlichkeit. [Responsibility and altruistic personality.]. Zeitschrift Für Sozialpsychologie, 25(3), 217–226.

Bierhoff, H. W., Klein, R., & Kramp, P. (1991). Evidence for the altruistic personality from data on accident research. Journal of Personality, 59(2), 263–280. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1991.tb00776.x

Bjereld, Y., Daneback, K., Löfstedt, P., Bjarnason, T., Tynjälä, J., Välimaa, R., & Petzold, M. (2017). Time trends of technology mediated communication with friends among bullied and not bullied children in four Nordic countries between 2001 and 2010. Child: Care Health and Development, 43(3), 451–457. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12409

Bondü, R., Rothmund, T., & Gollwitzer, M. (2016). Mutual long-term effects of school bullying, victimization, and justice sensitivity in adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 48, 62–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.01.007

Brunstein Klomek, A., Sourander, A., Gould, M., Klomek, A. B., Sourander, A., & Gould, M. (2010). The association of suicide and bullying in childhood to young adulthood: A review of cross-sectional and longitudinal research findings. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 55(5), 282–288. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371005500503

Callaghan, M., Kelly, C., & Molcho, M. (2019). Bullying and bystander behaviour and health outcomes among adolescents in Ireland. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 73(5), 416–421. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2018-211350

Caroli, M. E., De, & Sagone, E. (2014). Belief in a just world, prosocial behavior, and moral disengagement in adolescence. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 116, 596–600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.263

Correia, I., & Dalbert, C. (2008). School bullying: Belief in a personal just world of bullies, victims, and defenders. European Psychologist, 13(4), 248–254. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040.13.4.248

Correia, I., Salvado, S., & Alves, H. V. (2016). Belief in a just world and self-efficacy to promote justice in the world predict helping attitudes, but only among volunteers. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 19, E28.

Dalbert, C. (1997). Coping with an unjust fate: The case of structural unemployment. Social Justice Research, 10(2), 175–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02683311

Dalbert, C. (1999). The world is more just for me than generally: About the personal belief in a just world scale’s validity. Social Justice Research, 12(2), 79–98. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022091609047

Dalbert, C. (2001). The justice motive as a personal resource: Dealing with challenges and critical life events. Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

Dalbert, C. (2002). Beliefs in a just world as buffer against anger. Social Justice Research, 15, 123–145.

Dalbert, C., & Donat, M. (2015). Belief in a just world. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences: Second Edition (Vol. 2). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.24043-9

Davis, M. H. (1980). A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology, 85–104.

Davis, M. H. (1983). Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44(1), 113–126.

Davis, M. H. (2018). Empathy: A social psychological approach. Routledge.

Donat, M., Knigge, M., & Dalbert, C. (2018). Being a good or a just teacher: Which experiences of teachers’ behavior can be more predictive of school bullying? Aggressive Behavior, 1, 29–39. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21721

Donat, M., Peter, F., Dalbert, C., & Kamble, S. V. (2016). The meaning of students’ personal belief in a just world for positive and negative aspects of school-specific well-being. Social Justice Research, 29(1), 73–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-015-0247-5

Donat, M., Rüprich, C., Gallschütz, C., & Dalbert, C. (2020). Unjust behavior in the digital space: the relation between cyber-bullying and justice beliefs and experiences. Social Psychology of Education, 23(1), 101–123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-019-09530-5

Donat, M., Umlauft, S., Dalbert, C., & Kamble, S. V. (2012). Belief in a just world, teacher justice, and bullying behavior. Aggressive Behavior, 38(3), 185–193. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21421

Donat, M., Wolgast, A., & Dalbert, C. (2018). Belief in a just world as a resource of victimized students. Social Justice Research, 31(2), https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-018-0307-8

Dunn, T. J., Baguley, T., & Brunsden, V. (2014). From alpha to omega: A practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. 399–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12046

Engen, H. G., & Singer, T. (2013). Empathy circuits. In Current Opinion in Neurobiology (Vol. 23, Issue 2, pp. 275–282). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2012.11.003

Engert, V., Plessow, F., Miller, R., Kirschbaum, C., & Singer, T. (2014). Cortisol increase in empathic stress is modulated by emotional closeness and observation modality. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 45, 192–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.04.005

Erle, T. M., & Topolinski, S. (2015). Spatial and empathic perspective-taking correlate on a dispositional level. Social Cognition, 33(3), 187–210. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2015.33.3.187

Espelage, D. L., Hong, J. S., Kim, D. H., & Nan, L. (2018). Empathy, attitude towards bullying, theory-of-mind, and non-physical forms of bully perpetration and victimization among U.S. middle school students. Child and Youth Care Forum, 47(1), 45–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-017-9416-z

Forsberg, C., Thornberg, R., & Samuelsson, M. (2014). Bystanders to bullying: fourth- to seventh-grade students’ perspectives on their reactions. Research Papers in Education, 29(5), 557–576. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2013.878375

Fousiani, K., Michaelides, M., & Dimitropoulou, P. (2019). The effects of ethnic group membership on bullying at school: when do observers dehumanize bullies? Journal of Social Psychology, 159(4), 431–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2018.1505709

Fraley, R. C., Waller, N. G., & Brennan, K. A. (2000). An item response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(2), 350–365. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.78.2.350

Fredrick, S. S., Jenkins, L. N., & Ray, K. (2020). Dimensions of empathy and bystander intervention in bullying in elementary school. Journal of School Psychology, 79(December 2018), 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2020.03.001

Frick, P. J., Ray, J. V., Thornton, L. C., & Kahn, R. E. (2014). Can callous-unemotional traits enhance the understanding, diagnosis, and treatment of serious conduct problems in children and adolescents? A comprehensive review. Psychological Bulletin, 140(1), 1–57. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033076

Garandeau, C. F., Vartio, A., Poskiparta, E., & Salmivalli, C. (2016). School bullies’ intention to change behavior following teacher interventions: Effects of empathy arousal, condemning of bullying, and blaming of the perpetrator. Prevention Science, 17(8), 1034–1043. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-016-0712-x

Garnefski, N., & Kraaij, V. (2018). Specificity of relations between adolescents’ cognitive emotion regulation strategies and symptoms of depression and anxiety. Cognition and Emotion, 32(7), 1401–1408. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2016.1232698

Gasser, L., & Keller, M. (2009). Are the competent the morally good? Perspective taking and moral motivation of children involved in bullying. Social Development, 18(4), 798–816. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00516.x

Gehlbach, H. (2004). A new perspective on perspective taking. European Science Editing, 38(2), 35–37. https://doi.org/10.1023/B

Gehlbach, H., Young, L. V., & Roan, L. K. (2012). Teaching social perspective taking: How educators might learn from the Army. Educational Psychology, 32(3), 295–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2011.652807

Gniewek, A., Wojnarowska, A., & Szuster, A. (2018). On the unexpected consequences of perspective taking: Influence of spatial perspective rotation on infra-humanization. Studia Psychologica, 60(4), 209–225. https://doi.org/10.21909/sp.2018.04.763

Gini, G., Albiero, P., Benelli, B., & Altoe, G. (2007). Does empathy predict adolescents’ bullying and defending behavior? Aggressive Behavior: Official Journal of the International Society for Research on Aggression, 33(5), 467–476.

Gini, G., Pozzoli, T., Borghi, F., & Franzoni, L. (2008). The role of bystanders in students’ perception of bullying and sense of safety. Journal of School Psychology, 46(6), 617–638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2008.02.001

Hafer, C. L., & Sutton, R. (2016). Belief in a just world. Handbook of social justice theory and research (pp. 145–160). Springer.

Hasking, P. A. (2007). Reinforcement sensitivity, coping, and delinquent behaviour in adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 30(5), 739–749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.11.006

Hayes, A. F., Coutts, J. J., & But, R. (2020). Use omega rather than Cronbach’s alpha for estimating reliability. But… Communication Methods and Measures, 00(00), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2020.1718629

Hektner, J. M., & Swenson, C. A. (2011). Links from teacher beliefs to peer victimization and bystander intervention: Tests of mediating processes. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 32(4), 516–536. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431611402502

Hoffman, M. L. (2001). A comprehensive theory of prosocial moral development (D. Stipek & A. Bohart (eds.); Constructi, pp. 61–86). American Psychological Association.

Kamble, S. V., & Dalbert, C. (2012). Belief in a just world and wellbeing in Indian schools. International Journal of Psychology, 47(4), 269–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207594.2011.626047

Katsaras, G. N., Vouloumanou, E. K., Kourlaba, G., Kyritsi, E., Evagelou, E., & Bakoula, C. (2018). Bullying and suicidality in children and adolescents without predisposing factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Adolescent Research Review, 3(2), 193–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-018-0081-8

Kaltiala-Heino, R., Rimpel?, M., Rantanen, P., & Rimpel?, A. (2000). Bullying at school - An indicator of adolescents at risk for mental disorders. Journal of Adolescence, 23(6), 661–674. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.2000.0351

Lee, Y. H., & Ying, Z. (2015). A mixture cure-rate model for responses and response times in time-limit tests. Psychometrika, 80(3), 748–775. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11336-014-9419-8

Lerner, M. J. (1980). The belief in a just world. In The belief in a just world: A fundamental delusion. Springer US, 9–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-0448-5_2

Lewis, M., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (1979). Toward a theory of social cognition: The development of self. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 1979(4), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/cd.23219790403

Lipkus, I. M., & Siegler, I. C. (1993). The belief in a just world and perceptions of discrimination. The Journal of Psychology, 127(4), 465–474.

Maeda, R. (2003). Empathy, emotion regulation, and perspective taking as predictors of children’s participation in bullying [University of Washington]. https://elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=8838692

Malti, T., & Perren, S. (2011). Social competence. In Encyclopedia of Adolescence (Vol. 2). Elsevier Inc. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-373951-3.00090-9

Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self and society (Vol. 111). University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.5840/schoolman19361328

Meyer, M. L., & Lieberman, M. D. (2016). Social working memory training improves perspective-taking accuracy. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 7(4), 381–389. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550615624143

Nickerson, A. B., Aloe, A. M., & Werth, J. M. (2015). The relation of empathy and defending in bullying: A meta-analytic investigation. School Psychology Review, 44(4), 372–390. https://doi.org/10.17105/spr-15-0035.1

Oberski, D. (2015). lavaan.survey: An R package for complex survey analysis of structural equation models. Journal of Statistical Software Analysis of Structural Equation Models VV(II, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-23413-6_7

Olweus, D. (1994). Bullying at school. In L. R. Huesmann (Ed.), Aggressive Behavior: Current Perspectives (pp. 97–130). Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-9116-7_5

Olweus, D., Limber, S. P., & Breivik, K. (2019). Addressing specific forms of bullying: A large-scale evaluation of the Olweus bullying prevention program. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 1(1), 70–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-019-00009-7

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school: what we know and what we can do . Blackwell.

Peter, F., Donat, M., Umlauft, S., & Dalbert, C. (2013). Einführung in die Gerechtigkeitspsychologie BT - Gerechtigkeit in der Schule (C. Dalbert (ed.); pp. 11–32). Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-93128-9_1

Piaget, J. (1928). La causalité che l’enfant. British Journal of Psychology General Section, 18(3), 276–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8295.1928.tb00466.x

Piaget, J. (1952). The origins of intelligence in children. When thinking begins (pp. 25–36). International University Press. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0051916

Piaget, J. (2008). Intellectual evolution from adolescence to adulthood. Human Development, 51(1), 40–47. https://doi.org/10.1159/000112531

Polanin, J. R., Espelage, D. L., & Pigott, T. D. (2012). A meta-analysis of school-based bullying prevention programs’ effects on bystander intervention behavior. School Psychology Review, 41(1), 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2012.12087375

Pouwels, J. L., van Noorden, T. H. J., Lansu, T. A. M., & Cillessen, A. H. N (2018). The participant roles of bullying in different grades: Prevalence and social status profiles. Social Development, 27(4), 732–747. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12294

Pozzoli, T., Gini, G., & Thornberg, R. (2017). Getting angry matters: Going beyond perspective taking and empathic concern to understand bystanders’ behavior in bullying. Journal of Adolescence, 61(September), 87–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.09.011

R Development Core Team (2009). R: A language and environment for statistical computing [Computer software manual]. https://www.r-project.org/

Ranger, J., & Kuhn, J. T. (2017). Detecting unmotivated individuals with a new model-selection approach for Rasch models. Psychological Test and Assessment Modeling, 59(3), 269–295.

Revelle, W. (2019). Using R and the psych package to find ω. 1–20. www.personality-project.org/r/tutorials/HowTo/omega.tutorial/omega.pdf

Revelle, W., & Zinbarg, R. E. (2008). Coefficients alpha, beta, omega and the glb: comments on Sijtsma. Psychometrika, 1, 1–14.

Rigby, K., & Slee, P. T. (1993). Dimensions of interpersonal relation among Australian children and implications for psychological well-being. In The Journal of Social Psychology (Vol. 133, Issue 1, pp. 33–42). Heldref Publications. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1993.9712116

Rosseel, Y., Oberski, D., Byrnes, J., Vanbrabant, L., Savalei, V., Merkle, E. C., Hallquist, M., & Chow, M. (2018). Package lavaan. http://lavaan.org

Salmivalli, C., Lagerspetz, K., Björkqvist, K., Österman, K., & Kaukiainen, A. (1996). Bullying as a group process: Participant roles and their relations to social status within the group. Aggressive Behavior, 22(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2337(1996)22:1<1::AID-AB1>3.0.CO;2-T

Schäfer, M., & Korn, S. (2004). Bullying als Gruppenphänomen. Zeitschrift Für Entwicklungspsychologie Und Pädagogische Psychologie, 36(1), 19–29. https://doi.org/10.1026/0049-8637.36.1.19

Schweizer, K. (2011). On the changing role of Cronbach?s ? in the evaluation of the quality of a measure. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000069

Selman, R. L. (1981). The development of interpersonal competence: The role of understanding in conduct. Developmental Review, 1(4), 401–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/0273-2297(81)90034-4

Shelton, A. L., Clements-Stephens, A. M., Lam, W. Y., Pak, D. M., & Murray, A. J. (2012). Should social savvy equal good spatial skills? The interaction of social skills with spatial perspective taking. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 141(2), 199–205. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024617

Smith, P. K. (2014). Understanding school bullying: Its nature and prevention strategies. SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473906853

Soper, D. S. (2020). A-priori sample size calculator for structural equation models [software].

Stevens, V., Van Oost, P., & De Bourdeaudhuij, I. (2000). The effects of an anti-bullying intervention programme on peers’ attitudes and behaviour. Journal of Adolescence, 23(1), 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.1999.0296

Strelan, P. (2007). The prosocial, adaptive qualities of just world beliefs: Implications for the relationship between justice and forgiveness. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(4), 881–890. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.02.015

Strohmeier, D., Spiel, C., & Gradinger, P. (2008). Social relationships in multicultural schools: Bullying and victimization. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 5(2), 262–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405620701556664

Svetina, D., & Rutkowski, L. (2014). Detecting differential item functioning using generalized logistic regression in the context of large-scale assessments. Meredith 1993, 1–17.

Swearer, S. M., & Hymel, S. (2015). Understanding the psychology of bullying: Moving toward a social-ecological diathesis-stress model. American Psychologist, 70(4), 344–353. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038929

Thornberg, R., & W?nstr?m, L. (2018). Bullying and its association with altruism toward victims, blaming the victims, andclassroom prevalence of bystander behavior.