Abstract

The present study examined the relationship between perceived uncertainty and depression/ anxiety symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic and it tested the moderating roles of resilience and perceived social support in this relationship. A cross-sectional study was conducted between March 31st and May 15th, 2020, using an online, multi-language, international survey built within Qualtrics. We collected data on sociodemographic features, perceived uncertainty, perceived social support, depression and anxiety symptoms, and resilience. A moderation model was tested using model 2 of Hayes’ PROCESS macro for SPSS. The study included 3786 respondents from 94 different countries, 47.7% of whom reported residence in the United States of America. Results demonstrated that higher perceived uncertainty was associated with more symptoms of depression and anxiety. Higher resilience levels and higher perceived social support were associated with fewer depression and anxiety symptoms. The moderation hypotheses were supported; the relationship between uncertainty and symptoms of depression and anxiety decreased as levels of resilience increased and as perceived social support increased. The results suggest that resilience and social support could be helpful targets to reduce the negative effects of uncertainty on depression and anxiety symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has been spreading globally since late 2019 and the number of reported cases continues to climb in most countries of the world. As of October 3, 2021, there were approximately 235 million reported COVID-19 cases, with a case fatality rate of 2.04% (WHO, 2021). Despite these figures, and more than one year after the first case emerged in Wuhan, our understanding of the disease is still in its infancy; new information on the virus, on the disease course and its management, and on new experimental drugs and vaccines is accumulating daily. This accumulated information, questions, and doubts about the pandemic as well as confusion about guidelines and preventive efforts have contributed to increased uncertainty and anxiety (Altig et al., 2020; Koffman et al., 2020; Wilson et al., 2020).

Uncertainty reflects a lack of confidence in one’s ability to predict particular outcomes (Penrod, 2001) and it may exact significant burden on emotional and mental wellbeing (Eastwood et al., 2008; Eche et al., 2019; Perez et al., 2020). Uncertainty is common during disasters and public health crises (Afifi et al., 2012; Sim & Chua, 2004), wherein uncertainty has been associated with psychological distress (Afifi et al., 2012). In the context of COVID-19, high rates of anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress have been reported in many countries (Salari et al., 2020; Xiong et al., 2020), and one study found that uncertainty stress during the pandemic was positively related to depression and anxiety symptoms (Wang et al., 2021). To date, however, no studies have examined factors that buffer the relationship between uncertainty and negative mental health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, we sought to extend previous research by examining factors that may buffer the relationship between uncertainty and psychological distress during the pandemic.

Among these factors, we examined resilience, which can be defined as “the ability to achieve positive outcomes despite exposure to substantial risk or adversity” (Thurston et al., 2018, p. 115). Resilience is negatively related to negative mental health states, including depression, anxiety, and negative affect; and resilience is positively related to positive mental health states, such as positive affect (Färber & Rosendahl, 2020; Hu et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2013). Moreover, a wide range of research demonstrates the protective role of resilience against negative psychological outcomes following stressful life events (Masten & Obradović, 2008; Rutter, 2012). Therefore, we expected that resilience would moderate the relationship between uncertainty and psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic such that the relationship between uncertainty and distress would be weaker for individuals with high resilience.

In addition to resilience, social support is another factor that can potentially reduce vulnerability to psychological distress. Social support, or “support accessible to an individual through social ties to other individuals, groups, and the larger community” (Lin et al., 1979, p. 109), is negatively correlated with mental health conditions, such as anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder in various contexts (Dadi et al., 2020; Gariépy et al., 2016; Harandi et al., 2017; Nyqvist et al., 2013; Santini et al., 2015; Tengku Mohd et al., 2019; Wortman, 1984), including during natural and public health crises (Grills-Taquechel et al., 2011; Neria et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2018) and during the COVID-19 pandemic (Fang et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021; Özmete & Pak, 2020; Sun & Lu, 2020; Sun et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2020). Previous research has shown that social support serves as a buffer, protecting against the negative effects that stressful life events can have on mental health (Felix & Afifi, 2015). Moreover, research shows that social support moderates the relationship between uncertainty and psychological distress (Neville, 1998).

The current study aimed to further examine the relationship between perceived uncertainty and psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic by testing the moderating roles of resilience and perceived social support in the relationship between uncertainty and symptoms of depression and anxiety. We predicted that higher levels of resilience and perceived social support would buffer the impact of perceived uncertainty on symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Methods

A cross-sectional, survey-based study was conducted between March 31st and May 15th, 2020, using Qualtrics © LLC survey software. The goal of the survey was to learn about respondents’ experiences during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic; the survey consisted of several psychosocial measures related to stress and resilience, questions regarding respondents’ current and pre-pandemic beliefs and experiences (e.g., mood, substance use, sleep, etc.), and a delay discounting task. In addition to an English language version, 7 other translated versions of the survey (French, Spanish, Arabic, Italian, German, Russian, and Chinese) were available online. Links to the surveys were distributed via email circulation in professional and social groups (e.g., American Psychosomatic Society, Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, National Institutes of Health, and University of Minnesota) as well as via Facebook/Instagram and other social media advertisements. The survey took approximately 15 min to complete; it was anonymous; and no incentive was provided to respondents. Participants were qualified for the study if they were 18 years of age or older and provided an electronic consent at the start of the survey. All study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Minnesota (approval number STUDY00009374).

Measures

Respondent Characteristics

Participants responded to questions regarding their age, sex at birth, highest level of education completed, marital status, employment status, country of residence, and whether or not they had a chronic disease. These items were translated from English to the other survey languages by native speakers of each language and then verified by experts.

Perceived Uncertainty

Participants reported to what extent they have felt uncertain in the time since COVID-19 began spreading. The response scale ranged from 0 to 5 (0 = not at all; 1 = slightly; 2 = somewhat; 3 = moderately; 4 = quite a bit; 5 = a lot). This item was translated from English to the other survey languages for this study (details provided in the Supplementary Materials).

Perceived Social Support

Participants reported to what extent they have felt socially supported in the time since COVID-19 began spreading. The response scale ranged from 0 to 5 (0 = not at all; 1 = slightly; 2 = somewhat; 3 = moderately; 4 = quite a bit; 5 = a lot). This item was translated from English to the other survey languages for this study by native speakers of each language (details provided in the Supplementary Materials).

Depression and Anxiety Symptoms

The 4-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-4) (Kroenke et al., 2009) was used to collect data on depression and anxiety symptoms. PHQ-4 scores range from 0 to 12; and Cronbach’s alpha for this measure was 0.87 in this study. When available, existing translations of this measure were used; in addition, native speakers of each language translated the questions and experts verified the final items (details provided in the Supplementary Materials).

Resilience

The Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) (Smith et al., 2008), was used to assess resilience. It is a 6-item measure designed “to assess the ability to bounce back or recover from stress” (Smith et al., 2008, p. 194). Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 to 5 and were averaged to create a total score, with higher scores indicating greater resilience. Cronbach’s alpha for this measure was 0.85 in this study. When available, existing translations of this measure were used; in addition, native speakers of each language translated the questions and experts verified the final items (details provided in the Supplementary Materials).

Statistical Analysis

Only participants who responded to questions about perceived uncertainty, perceived social support, PHQ-4, and BRS were included in this study. Statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23.0. Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r) were used to examine the relationships between perceived uncertainty, depression/ anxiety symptoms, resilience, and perceived social support. A moderation model was tested using model 2 of Hayes’ PROCESS macro (version 3.5), which uses OLS regression (Hayes, 2017). Symptoms of depression/ anxiety were specified as the dependent variable and uncertainty was specified as the primary independent variable; social support and resilience were both specified as moderators. All variables involved in interactions were mean-centered for the analysis. Significant moderation effects were probed at the mean and at one standard deviation above and below the mean of the moderators (resilience and perceived social support).

Results

The final sample of respondents included 3786 individuals from 94 different countries, 47.7% of whom reported residence in the United States of America. The mean age of participants was 38.6 (SD = 14) years and most participants were female (70.8%). The main participant sociodemographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

About one out of three participants (33%) had mild depression/anxiety symptoms (PHQ-4 score between 3 and 5), about one out of three participants had either moderate (score between 6–8; 16.5%) or severe (score between 9–12, 15.3%) symptoms, and the remaining participants had PHQ-4 scores below 3. Correlations between depression/ anxiety symptoms, perceived uncertainty, resilience, and perceived social support are presented in Table 2. The results demonstrate that higher perceived uncertainty was associated with more depression/ anxiety symptoms (r = 0.54; p < 0.001) and that higher resilience levels and higher perceived social support were associated with fewer symptoms of depression and anxiety (r = -0.49, p < 0.001 and r = -0.25, p < 0.001, respectively).

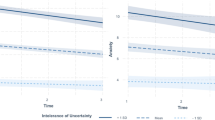

The overall moderation model was significant (F (5, 3780) = 585.6, p < 0.0001) and accounted for 44% of the variance in examining the relationship between perceived uncertainty and symptoms of depression and anxiety. The moderation hypotheses were supported; the relationship between uncertainty and symptoms of depression and anxiety decreased as levels of resilience increased (B = -0.16; p < 0.0001) and as perceived social support increased (B = -0.10; p < 0.0001) (Table 3); the different conditional effects are illustrated in Fig. 1. Similar results were found when adjusting for age, sex, marital status, level of education, employment status, and whether or not respondents had a chronic disease.

Conditional effects of perceived uncertainty on depression/ anxiety symptoms at different levels of perceived social support and resilience, n = 3786. PHQ4: 4-item Patient Health Questionnaire (Kroenke et al., 2009) measure of depression/ anxiety symptoms. Perceived uncertainty, perceived social support, and resilience were mean-centered prior to analysis. A, B, and C: Effects of perceived uncertainty on depression/ anxiety symptoms were probed at the mean (mean level), at one standard deviation above the mean (high level), and at one standard deviation below the mean (low level) of perceived social support across different levels of resilience

Discussion

The current study revealed a positive correlation between feelings of uncertainty and symptoms of depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. As hypothesized, this association was moderated by both resilience and perceived social support, suggesting that higher levels of resilience and perceived social support buffer the impact of perceived uncertainty on depression and anxiety symptoms.

Previous studies highlight the role of uncertainty in the development and maintenance of mental disorders (Carleton, 2012, 2016; Oglesby et al., 2016). Feeling uncertain may decrease one’s sense of perceived control, which may, in-turn, lead to maladaptive behaviors (Bomyea et al., 2015; Carleton, 2016) that affect physical and mental wellbeing (Devanand, 2002; Satin et al., 2009). Consistent with these and other studies that have consistently found a negative impact of uncertainty on mental health (Eastwood et al., 2008; Eche et al., 2019; Liao et al., 2008; Perez et al., 2020), we found that perceived uncertainty was positively related to symptoms of depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the context of COVID-19, eliminating uncertainty and the multitude of questions related to the disease and its impact on daily living is likely not realistic. Therefore, a more viable approach to mitigating the negative impact of uncertainty at this time calls for efforts to bolster factors that can mitigate the negative consequences of uncertainty. In our study, two protective factors were identified: psychological resilience and social support. Our finding that resilience serves as a moderator corroborates previous studies’ findings on the role of resilience in buffering the effects of diverse stressors on mental health outcomes (Anyan & Hjemdal, 2016), especially during global virus outbreaks such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) (Bonanno et al., 2008) and COVID-19 (Ben Salah et al., 2021; Coulombe et al., 2020; Havnen et al., 2020). Resilience is increasingly considered a process of adaptation that can potentially be trained (Chmitorz et al., 2018; Kalisch et al., 2015, 2017). Different interventions can be implemented to build and promote resilience during and after exposure to stressors (Chmitorz et al., 2018), which may be especially beneficial among individuals with low and medium levels of resilience. These interventions can even be adapted for virtual delivery of therapy or for teletherapy to better fit the safety guidelines of living during a pandemic (Chmitorz et al., 2018; Ungar & Theron, 2020).

Social support is also considered a protective factor against mental health disorders following diverse crises and other negative life events (Grills-Taquechel et al., 2011; Hill & Hamm, 2019; Neria et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2018). Indeed, initial research during the COVID-19 pandemic found that social support was negatively related to symptoms of depression and anxiety (Mariani et al., 2020; Özmete & Pak, 2020); and this study found that social support mitigated the relationship between uncertainty and symptoms of depression and anxiety. Researchers have drawn from several theories to explain why social support may serve as a protective factor in the face of stress (Prati & Pietrantoni, 2010). For instance, researchers have speculated that when individuals perceive that they have the support of others, who will provide necessary help when needed, a person’s self-efficacy or perceived ability to respond to the stressor (e.g., COVID-19) may be bolstered or the potential for harm posed by the stressor may be reframed (Özmete & Pak, 2020; Prati & Pietrantoni, 2010). This highlights the importance of increasing coping capacity by strengthening individuals’ ability to provide social support in addition to services that strengthen perceptions of social support during stressful and uncertain life circumstances, such as those experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, interventions promoting emotional, instrumental, informational, or companionship support may help reduce psychological burdens related to uncertainty.

We point-out some limitations in this study that should be addressed in future research. First, although this study used face-valid items to measure perceived social support and perceived uncertainty, these were single-item measures. Second, the cross-sectional design of the study allows examination of associations, but not answers to questions regarding causality and processes. As such, future longitudinal studies should investigate these relationships over time. Despite these limitations, this study is among the first few studies to measure perceived uncertainty during the pandemic and to explore its relationship with mental health. Another strength is this study’s focus on protective factors; in fact, this is the first study to explore the protective role of social support and resilience on the relationship between uncertainty and depression and anxiety, which enhances the clinical and therapeutic relevance of the findings.

In conclusion, COVID-19 has triggered an unprecedented increase in uncertainty associated with daily living. Our results show that perceived uncertainty is associated with symptoms of depression/ anxiety, but this relationship is buffered by perceived social support and psychological resilience. Interventions to promote resilience and enhance social support during the COVID-19 pandemic and other uncertain life circumstances may attenuate the negative health impacts of these stressful situations.

Data Availability

The data described in this article are openly available in the Open Science Framework at: https://osf.io/qebpy/?view_only=005feabbc8d5430f85d4eecc8b91fa73

References

Afifi, W.A., Felix, E.D., & Afifi, T.D. (2012). The impact of uncertainty and communal coping on mental health following natural disasters. Anxiety Stress and Coping, 25(3), 329–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2011.603048.

Altig, D., Baker, S., Barrero, J. M., Bloom, N., Bunn, P., Chen, S., et al. (2020). Economic uncertainty before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Public Economics, 191, Article 104274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104274

Anyan, F., & Hjemdal, O. (2016). Adolescent stress and symptoms of anxiety and depression: Resilience explains and differentiates the relationships. Journal of Affective Disorders, 203, 213–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.031.

Ben Salah, A., DeAngelis, B.N., & al’Absi, M. (2021). Resilience and the role of depressed and anxious mood in the relationship between perceived social isolation and perceived sleep quality during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 28(3), 277–285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-020-09945-x.

Bomyea, J., Ramsawh, H., Ball, T.M., Taylor, C.T., Paulus, M.P., Lang, A.J., & Stein, M.B. (2015). Intolerance of uncertainty as a mediator of reductions in worry in a cognitive behavioral treatment program for generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 33, 90–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.05.004.

Bonanno, G.A., Ho, S.M., Chan, J.C., Kwong, R.S., Cheung, C.K., Wong, C.P., & Wong, V.C. (2008). Psychological resilience and dysfunction among hospitalized survivors of the SARS epidemic in Hong Kong: A latent class approach. Health Psychology, 27(5), 659–667. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.27.5.659.

Carleton, R.N. (2012). The intolerance of uncertainty construct in the context of anxiety disorders: Theoretical and practical perspectives. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 12(8), 937–947. https://doi.org/10.1586/ern.12.82.

Carleton, R.N. (2016). Into the unknown: A review and synthesis of contemporary models involving uncertainty. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 39, 30–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.02.007.

Chmitorz, A., Kunzler, A., Helmreich, I., Tüscher, O., Kalisch, R., Kubiak, T., . . . Lieb, K. (2018). Intervention studies to foster resilience - A systematic review and proposal for a resilience framework in future intervention studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 59, 78-100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.11.002.

Coulombe, S., Pacheco, T., Cox, E., Khalil, C., Doucerain, M.M., Auger, E., & Meunier, S. (2020). Risk and resilience factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: A snapshot of the experiences of Canadian workers early on in the crisis. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, Article 580702. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.580702

Dadi, A.F., Akalu, T.Y., Baraki, A.G., & Wolde, H.F. (2020). Epidemiology of postnatal depression and its associated factors in Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 15(4), Article e0231940. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231940

Devanand, D.P. (2002). Comorbid psychiatric disorders in late life depression. Biological Psychiatry, 52(3), 236–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01336-7.

Eastwood, J.A., Doering, L., Roper, J., & Hays, R.D. (2008). Uncertainty and health-related quality of life 1 year after coronary angiography. American Journal of Critical Care, 17(3), 232–242. https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2008.17.3.232

Eche, I.J., Aronowitz, T., Shi, L., & McCabe, M.A. (2019). Parental uncertainty: Parents’ perceptions of health-related quality of life in newly diagnosed children with cancer. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 23(6), 609–618. https://doi.org/10.1188/19.CJON.609-618.

Fang, X.H., Wu, L., Lu, L.S., Kan, X.H., Wang, H., Xiong, Y.J., et al. (2021). Mental health problems and social supports in the COVID-19 healthcare workers: A Chinese explanatory study. BMC Psychiatry, 21(1), Article 34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02998-y

Färber, F., & Rosendahl, J. (2020). Trait resilience and mental health in older adults: A meta-analytic review. Personality and Mental Health. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmh.1490.

Felix, E., & Afifi, W. (2015). The role of social support on mental health after multiple wildfire disasters. Journal of Community Psychology, 43(2), 156–170. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21671

Gariépy, G., Honkaniemi, H., & Quesnel-Vallée, A. (2016). Social support and protection from depression: Systematic review of current findings in Western countries. British Journal of Psychiatry, 209(4), 284–293. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.115.169094.

Grills-Taquechel, A.E., Littleton, H.L., & Axsom, D. (2011). Social support, world assumptions, and exposure as predictors of anxiety and quality of life following a mass trauma. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25(4), 498–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.12.003.

Harandi, T.F., Taghinasab, M.M., & Nayeri, T.D. (2017). The correlation of social support with mental health: A meta-analysis. Electron Physician, 9(9), 5212–5222. https://doi.org/10.19082/5212.

Havnen, A., Anyan, F., Hjemdal, O., Solem, S., GurigardRiksfjord, M., & Hagen, K. (2020). Resilience moderates negative outcome from stress during the COVID-19 pandemic: A moderated-mediation approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), Article 6461. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186461

Hayes, A.F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Hill, E.M., & Hamm, A. (2019). Intolerance of uncertainty, social support, and loneliness in relation to anxiety and depressive symptoms among women diagnosed with ovarian cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 28(3), 553–560. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4975.

Hu, T., Zhang, D., & Wang, J. (2015). A meta-analysis of the trait resilience and mental health. Personality and Individual Differences, 76, 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.11.039

Kalisch, R., Müller, M.B., & Tüscher, O. (2015). A conceptual framework for the neurobiological study of resilience. The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 38, Article e92. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X1400082X

Kalisch, R., Baker, D.G., Basten, U., Boks, M.P., Bonanno, G.A., Brummelman, E., . . . Kleim, B. (2017). The resilience framework as a strategy to combat stress-related disorders. Nature Human Behaviour, 1(11), 784-790. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-017-0200-8.

Koffman, J., Gross, J., Etkind, S.N., & Selman, L. (2020). Uncertainty and COVID-19: How are we to respond? Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 113(6), 211–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/0141076820930665.

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R.L., Williams, J.B., & Löwe, B. (2009). An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: The PHQ-4. Psychosomatics, 50(6), 613–621. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613.

Lee, J. H., Nam, S. K., Kim, A.-R., Kim, B., Lee, M. Y., & Lee, S. M. (2013). Resilience: A meta-analytic approach. Journal of Counseling and Development, 91, 269–279. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2013.00095.x

Li, F., Luo, S., Mu, W., Li, Y., Ye, L., Zheng, X., et al. (2021). Effects of sources of social support and resilience on the mental health of different age groups during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatry, 21(1), Article 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-03012-1

Liao, M.N., Chen, M.F., Chen, S.C., & Chen, P.L. (2008). Uncertainty and anxiety during the diagnostic period for women with suspected breast cancer. Cancer Nursing, 31(4), 274–283. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NCC.0000305744.64452.fe.

Lin, N., Simeone, R.S., Ensel, W.M., & Kuo, W. (1979). Social support, stressful life events, and illness: A model and an empirical test. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 20(2), 108–119. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136433

Mariani, R., Renzi, A., Di Trani, M., Trabucchi, G., Danskin, K., & Tambelli, R. (2020). The impact of coping strategies and perceived family support on depressive and anxious symptomatology during the Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19) lockdown. Front Psychiatry, 11, Article 587724. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.587724

Masten, A.S., & Obradović, J. (2008). Disaster preparation and recovery: Lessons from research on resilience in human development. Ecology and Society, 13(1), Article 9. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-02282-130109

Neria, Y., Besser, A., Kiper, D., & Westphal, M. (2010). A longitudinal study of posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and generalized anxiety disorder in Israeli civilians exposed to war trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23(3), 322–330. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20522.

Neville, K. (1998). The relationships among uncertainty, social support, and psychological distress in adolescents recently diagnosed with cancer. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 15(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/104345429801500106.

Nyqvist, F., Forsman, A. K., Giuntoli, G., & Cattan, M. (2013). Social capital as a resource for mental well-being in older people: A systematic review. Aging & Mental Health, 17(4), 394–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2012.742490.

Oglesby, M.E., Raines, A.M., Short, N.A., Capron, D.W., & Schmidt, N.B. (2016). Interpretation bias for uncertain threat: A replication and extension. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 51, 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2015.12.006.

Özmete, E., & Pak, M. (2020). The Relationship between Anxiety Levels and Perceived Social Support during the Pandemic of COVID-19 in Turkey. Soc Work Public Health, 35(7), 603–616. https://doi.org/10.1080/19371918.2020.1808144.

Penrod, J. (2001). Refinement of the concept of uncertainty. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 34(2), 238–245. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01750.x.

Perez, M.N., Traino, K.A., Bakula, D.M., Sharkey, C.M., Espeleta, H.C., Delozier, A.M., . . . Mullins, L.L. (2020). Barriers to care in pediatric cancer: The role of illness uncertainty in relation to parent psychological distress. Psychooncology, 29(2), 304-310. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5248.

Prati, G., & Pietrantoni, L. (2010). The relation of perceived and received social support to mental health among first responders: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Community Psychology, 38(3), 403–417. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20371

Rutter, M. (2012). Resilience as a dynamic concept. Development and Psychopathology, 24(2), 335–344. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579412000028.

Salari, N., Hosseinian-Far, A., Jalali, R., Vaisi-Raygani, A., Rasoulpoor, S., Mohammadi, M., & Khaledi-Paveh, B. (2020). Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Global Health, 16(1), Article 57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w

Santini, Z.I., Koyanagi, A., Tyrovolas, S., Mason, C., & Haro, J.M. (2015). The association between social relationships and depression: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 175, 53–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.12.049.

Satin, J.R., Linden, W., & Phillips, M.J. (2009). Depression as a predictor of disease progression and mortality in cancer patients: A meta-analysis. Cancer, 115(22), 5349–5361. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.24561.

Sim, K., & Chua, H.C. (2004). The psychological impact of SARS: A matter of heart and mind. CMAJ, 170(5), 811–812. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.1032003.

Smith, B.W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P., & Bernard, J. (2008). The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15(3), 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705500802222972.

Sun, Q., & Lu, N. (2020). Social capital and mental health among older adults living in Urban China in the context of COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(21), Article 7947. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17217947

Sun, Y., Lin, S.Y., & Chung, K.K.H. (2020). University students’ perceived peer support and experienced depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic: The mediating role of emotional well-being. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24), Article 9308. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249308

Tengku Mohd, T.A.M., Yunus, R.M., Hairi, F., Hairi, N.N., & Choo, W.Y. (2019). Social support and depression among community dwelling older adults in Asia: A systematic review. British Medical Journal Open, 9(7), Article e026667. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026667

Thurston, I. B., Hardin, R., Kamody, R. C., Herbozo, S., & Kaufman, C. (2018) The moderating role of resilience on the relationship between perceived stress and binge eating symptoms among young adult women. Eating Behaviors, 29, 114–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2018.03.009

Ungar, M., & Theron, L. (2020). Resilience and mental health: How multisystemic processes contribute to positive outcomes. Lancet Psychiatry, 7(5), 441–448. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30434-1.

Wang, J., Mann, F., Lloyd-Evans, B., Ma, R., & Johnson, S. (2018). Associations between loneliness and perceived social support and outcomes of mental health problems: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), Article 156. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1736-5

Wang, X. L., Gao, L. Y., Miu, Q. F., Dong, X. D., Jiang, X. M., Su, S. M., et al. (2021). Perceived uncertainty stress and its predictors among residents in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 27(1), 265–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2021.1883692

WHO. (2021). Weekly epidemiological update on COVID-19. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19---5-october-2021. Accessed 7 Oct 2021.

Wilson, J.M., Lee, J., Fitzgerald, H.N., Oosterhoff, B., Sevi, B., & Shook, N.J. (2020). Job insecurity and financial concern during the COVID-19 pandemic are associated with worse mental health. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 62(9), 686–691. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000001962.

Wortman, C.B. (1984). Social support and the cancer patient. Conceptual and methodologic issues. Cancer, 53(10 Suppl), 2339–2362. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.1984.53.s10.2339.

Xiong, J., Lipsitz, O., Nasri, F., Lui, L.M.W., Gill, H., Phan, L., . . . McIntyre, R.S. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 55-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001.

Yang, X., Xiong, Z., Li, Z., Li, X., Xiang, W., & Yuan, Y. (2020). Perceived psychological stress and associated factors in the early stages of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic: Evidence from the general Chinese population. PLoS ONE, 15(12), Article e0243605. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0243605

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the help of the Stress & Resilience in the Face of Coronavirus (COVID-19) Survey team members and collaborators (Hailey Glewwe, Ryan Johnson, Luke Leufen, Ksenia F. Li, Huma Mamtiminm, Daniela Morales, Katania Myrie, Jake Robinson, Stephan Bongard, Bingshuo Li, Shah Alem, Svetlana Kuzmina, Susan Levenstein, Motohiro Nakajima, Marina Olmos, Georgi Vasilev, R. J. Solomon, Emna Bouguira, Emanuele Capuozzo).

Funding

Part of Dr. al’Absi’s time was supported by grants from the National Institute of Health (R01DA016351 and R01DA027232).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ben Salah, A., DeAngelis, B.N. & al’Absi, M. Uncertainty and psychological distress during COVID-19: What about protective factors?. Curr Psychol 42, 21470–21477 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03244-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03244-2