Abstract

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) is a serious health concern in prison populations. Most previous research in prisons has examined lifetime engagement in NSSI, but less is known about correlates and risk factors during imprisonment. Using Nock’s integrated theoretical model as a conceptual framework, the present study tested the mediation effect of psychopathy and the moderation effect of cognitive reappraisal skills in the association between childhood maltreatment and NSSI in prisoners. A total of 1042 Chinese male prisoners anonymously completed measures of childhood maltreatment, psychopathy and cognitive reappraisal, and their NSSI was assessed through structured interviews. Regression based tests of the conceptual model showed that childhood maltreatment was significantly associated with NSSI in prisoners, and this association was mediated by psychopathy. Cognitive reappraisal moderated the relationship between psychopathy and NSSI. Specifically, the relationship between psychopathy and NSSI was significant for prisoners with low levels of cognitive reappraisal but non-significant for those with high levels of cognitive reappraisal. These findings highlight the need to consider environmental and intrapersonal factors simultaneously when evaluating risks associated with NSSI in prison populations, and can inform prevention and intervention programs in prison settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) is defined as the deliberate, direct, and socially unacceptable destruction of one’s own body tissue without conscious suicidal intent (Nock, 2009). This high risk behavior is a significant and growing problem among prison inmates. Large scale studies revealed that 17%–18% of prisoners reported a lifetime history of NSSI, and 7%–9% engaged in NSSI while incarcerated (Carli et al., 2011; Favril, 2019; Favril et al., 2018; Knight et al., 2017). These prevalence rates were greater than the 4% who reported NSSI in the general population (Klonsky et al., 2003). In addition, NSSI in prison may threaten the safety and well-being of staff and prisoners and result in substantial monetary and human costs (DeHart et al., 2009).

Given these estimates of prevalence, it is important to identify risk and protective factors for NSSI among prisoners. This information could inform treatment programs for prisoners who are engaging in NSSI, as well as prevention programs for those who are at high risk for engaging in this behavior. In the current study, we conceptualized these risk and protective factors in terms of prisoners’ early environment and their current psychological characteristics. Specifically, we studied whether childhood maltreatment as an environmental factor, and psychopathy and cognitive reappraisal skills as individual characteristics, were associated with higher or lower risk for NSSI among prisoners. The research focused not only on the risk associated with these individual factors, but also on the risk associated with relations among these factors.

Childhood Maltreatment and NSSI

Childhood maltreatment (i.e., emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, as well as physical and emotional neglect) is an identified risk factor for NSSI (Liu et al., 2018). According to Nock’s (2009) integrated theoretical model of NSSI, maltreatment may contribute to a vulnerability that prevents the child from learning effective skills to cope with emotional distress, which may result in using NSSI as an ineffective coping method.

Considerable evidence indicates that childhood maltreatment is positively associated with NSSI in prison (e.g., Carli et al., 2010; Favril et al., 2020; Ford et al., 2020; Roe-Sepowitz, 2007). For example, a recent meta-analysis demonstrated that prisoners who had suffered childhood abuse (i.e., sexual, emotional, and physical abuse) had a 2.1- to 3.9-fold higher rate of NSSI behaviors than their counterparts with no history of childhood abuse (Favril et al., 2020). Similarly, in a sample of 468 male adult prisoners in the UK, Ford et al. (2020) found that prisoners who had suffered multiple adverse childhood experiences (e.g., childhood maltreatment) were substantially more likely to have a history of self-harming behavior within prison settings.

Although the association between childhood maltreatment and NSSI is well-established in prison populations, the mechanisms linking childhood maltreatment to prisoners’ NSSI remain unclear. The integrated theoretical model suggests that NSSI is caused by the interplay of distal environmental and proximal intrapersonal risk factors (Nock, 2009). Using this model as a conceptual framework, we investigated the joint effects of one environmental factor, namely childhood maltreatment (i.e., abuse and neglect), and two intrapersonal factors, namely psychopathy and cognitive reappraisal, on prisoners’ NSSI. More specifically, we examined the mediating role of psychopathy in the relationship between childhood maltreatment and NSSI in prison, as well as the moderating role of prisoners’ cognitive reappraisal in this association.

The Mediating Role of Psychopathy

Psychopathy is a personality trait that encompasses a constellation of egocentricity, impulsivity, and lack of such emotions as guilt and remorse, which is particularly prevalent among repeat offenders diagnosed with antisocial personality disorder (VandenBos, 2013). Considerable evidence has documented the link between childhood maltreatment and psychopathy in prisoners. For example, early physical and emotional traumatic experience was found to be positively associated with psychopathy among incarcerated adolescents (Campbell et al., 2004; Krischer & Sevecke, 2008). Graham et al. (2012) found that among imprisoned men convicted of sex offenses, those with a history of childhood abuse scored significantly higher on measures of psychopathy than those without such a history.

From a functional perspective, NSSI may be maintained through both automatic (i.e., reinforced by oneself; e.g., affect regulation) and social (i.e., reinforced by others; e.g., attention, avoidance-escape) reinforcement (Nock & Prinstein, 2004). Consistent with this model, prisoners with psychopathy may resort to NSSI to regulate the intensity of their emotions and to modify or regulate their social environment. According to Fadoir et al. (2019), prisoners who show secondary psychopathy (i.e., impulsive-antisocial behaviors) demonstrate dysregulated emotional processing, which may increase the risk of NSSI as a way to regulate aversive emotions. As for the latter, Power et al. (2016) reported that in their study, several prisoners used NSSI as a method of obtaining external rewards within the institutional context, such as desired medications or permission to move to a different cell or institution.

In addition, Power et al. (2016) reported that several prisoners in their study resorted to NSSI to avoid negative consequences (e.g., longer sentences, time in solitary confinement, and loss of privileges) that would occur as a result of violence against others. The fearlessness about death, pain tolerance, and cold heartedness that are characteristic of psychopathy may make some prisoners more likely to hurt themselves instead of others (Fadoir et al., 2019; Lobbestael et al., 2020). These studies suggest that psychopathy may serve as an important mediating variable in the link between childhood maltreatment and NSSI. That is, childhood maltreatment creates a vulnerability to psychopathy, which in turn increases the risk of NSSI.

The Moderating Role of Cognitive Reappraisal

Although childhood maltreatment may be significantly associated with prisoners’ NSSI through the mediating role of psychopathy, not all individuals who are exposed to maltreatment show psychopathy or NSSI in adulthood. Thus, it is important to explore factors that may diminish or increase (i.e., moderate) the strength of the associations among childhood maltreatment, psychopathy, and NSSI. According to Klonsky (2007), relief from unwanted emotions is the primary function for engaging in NSSI. Given that both childhood maltreatment and psychopathy are strongly related to negative affectivity (Blair et al., 2001; Jaffee, 2017), effective emotion regulation strategies (e.g., cognitive reappraisal) may buffer the adverse impacts of childhood maltreatment and psychopathy on NSSI.

Most researchers have considered that cognitive-emotion regulation includes several aspects (Hasking et al., 2017; Madjar et al., 2019; Robinson et al., 2019). For example, Gross and John (2003) proposed two specific strategies of emotion regulation: cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression, while Gratz and Roemer (2004) emphasized that the acceptance of experienced emotion is a core regulatory step. According to Gross’s process model of emotion regulation, emotions are generated and expressed over a multi-stage process, with various regulation strategies available at each stage (Wolff et al., 2019). The strategies such as acceptance, perspective taking, and expressive suppression were regarded as response-focused strategy, while cognitive reappraisal antecedent-focused emotion regulation strategies. Some studies documented that cognitive reappraisal are relatively more or equal successful in comparison to response-focused strategy (Gross, 1998; Hofmann et al., 2009). Hence, we only focused the role of cognitive reappraisal.

Cognitive reappraisal is one emotion regulation strategy that can reduce subjective negative emotional experiences through cognitive change (Gross & John, 2003). A large body of literature has shown that cognitive reappraisal reduces the risk and severity of NSSI, thus acting as a protective factor (for a review, see Voon et al., 2014a, 2014b). According to Fritz (2020), cognitive reappraisal may help individuals take a long view of life and consider the importance of the stressor “in the grand scheme of things.” That is, cognitive reappraisal may lessen the stressor’s negative emotional impact even if the person is unable to change anything about the stressor itself.

Previous research revealed that NSSI behaviors may be maladaptive attempts to cope with emotion dysregulation resulting from traumatic experiences in childhood and from associated psychopathy (Fadoir et al., 2019; Peh et al., 2017). Thus, individuals with low skills for cognitive reappraisal may be highly motivated to obtain the immediate benefits of NSSI (e.g., emotion regulation) with less concern for the long-term consequences of NSSI engagement (e.g., scarring, discomfort, and stigmatization; Hauber et al., 2019). By contrast, individuals with high skills for cognitive reappraisal are able to effectively cope with negative emotions at an early stage of an emotional process, and may thus be at lower risk of NSSI (Klosowska et al., 2019). Consequently, cognitive reappraisal might play a protective role in the relationship between psychopathy and NSSI, as well as in the relationship between childhood maltreatment and NSSI.

The Present Study

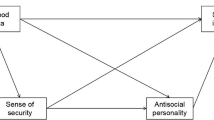

Given the high prevalence of NSSI in prisoners, we extended previous research by testing a moderated mediation model (see Fig. 1) of the relation between childhood maltreatment and prisoners’ NSSI. In this model, we tested the mediating effect of psychopathy and the moderating effect of cognitive reappraisal. Based on the literature review, we proposed the following hypotheses:

-

Hypothesis 1. Psychopathy will mediate the relationship between childhood maltreatment and prisoners’ NSSI;

-

Hypothesis 2. Skills for cognitive reappraisal will moderate (i.e., buffer) the association between childhood maltreatment and NSSI as well as the association between psychopathy and NSSI in a prison population.

Methods

Participants

Participants were men who were incarcerated in two moderate security male prisons located in Henan Province, Central China. A total of about 6000 prisoners were housed in ten blocks of these two prisons, and the sentences ranged from a few months to life imprisonment. We sampled 1286 prisoners from two blocks of the prisons. Exclusion criteria were inability to read (n = 45, 3.5%), mental illness (n = 21, 1.6%), and intellectual disability (n = 16, 1.2%). Because the purpose of the study was to assess the 12-month prevalence of prisoners’ NSSI in the prison environment, participants who were incarcerated for less than one year (n = 73, 5.7%) were also excluded. After these exclusions, there remained 1131 prisoners participating in the study. After data collection, an additional 89 participants were eliminated because of the tendency to indiscriminately select the same response (i.e., no intraindividual variability in item responses). The final sample size was 1042, and the effective response rate was 92.1%.

In the sample of 1042 participants, the mean age was 38.45 years (SD = 10.67 years, range = 20–71 years), and the mean length of time the men had spent in prison was 63.66 months (SD = 40.60, range = 12 to 228 months). Among this sample, 57.8% (n = 602) had been convicted of nonviolent crimes (e.g., property offenses, drug-related crimes), and 62.5% (n = 651) reported their place of residence as rural. Almost half (n = 511, 49.0%) were married or were cohabiting before they were in prison, 30.0% (n = 313) were single, and 21.0% (n = 218) were divorced or widowed.

Procedure

The study protocol was approved by the first author’s University Committee for Ethical Research, and was executed consistent with ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. The data were collected from November 2018 to January 2019, and the prisoners were invited to participate in this study. The participants were informed that the research was anonymous and they could stop at any time without penalty. Written informed consent was obtained from the prisoners, and no rewards were offered for their participation.

The whole study was conducted across two sessions. During the first session, participants completed self-report questionnaires (i.e., questionnaires regarding demographics, childhood maltreatment, psychopathy, and cognitive reappraisal) in groups of approximately 12–16 in a quiet room, supervised by an experimenter who was available to answer questions about the measures. Total administration time was around 20 min. During the second session, the interview measure of NSSI was conducted by masters-level students in clinical psychology. Each participant was interviewed individually in a private assessment room, and the interview took 10 min on average.

Measures

Non-suicidal Self-Injury (NSSI) in the correctional setting was assessed by the following question: “In the past 12 months, have you engaged in stabbing your skin, self-cutting, banging your head, burning yourself, biting yourself, or scratching your skin to deliberately harm yourself but without suicidal intent?” This question was derived from the Inventory of Statements About Self-Injury (ISAS; Klonsky & Glenn, 2009) and was scored during a structured interview designed for this study. All items were rated by the interviewer on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = never, 2 = once or twice, 3 = three to five times, to 4 = six times or more. Scores ranged from 4 to 24, with higher scores indicating higher frequency of NSSI. In the present study, Cronbach’ α for this measure was 0.87. Furthermore, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) indicated that the standardized factor loadings ranged from 0.71 to 0.84, and the one-factor model fit the data well: χ2/df = 2.93, TLI = 0.96, CFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.043, SRMR = 0.036.

Childhood maltreatment was measured by means of the short form of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ-SF; Bernstein et al., 2003). The CTQ-SF consists of five dimensions covering emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect, and each dimension has five items. A representative item was: “People in my family hit me so hard that it left me with bruises or marks.” Participants rated the items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never true) to 5 (very often true). The average score of all items was calculated as the final score, with higher scores reflecting more severe maltreatment in childhood. The Chinese version of this questionnaire has been demonstrated to be a reliable and valid measurement of childhood maltreatment (e.g., Gu et al., 2020). In the present study, Cronbach’ α was 0.88.

Cognitive reappraisal was measured by means of the cognitive reappraisal subscale of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ; Gross & John, 2003). This measure consists of 6 items (e.g., “When I want to feel less negative emotion, I change the way I’m thinking about the situation”), and participants rated each item on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Responses to items were averaged to yield a final score, and higher scores indicated higher cognitive reappraisal. This scale has been used in Chinese samples and demonstrated good reliability and validity (e.g., Zhao & Zhao, 2015). In the present study, Cronbach’ α was 0.80.

Psychopathy was measured using the psychopathy subscale of the 12-item Dirty Dozen (Jonason & Webster, 2010). This measure consists of four items (e.g., “I tend to be cynical”), and participants rated each item on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A final score was calculated by averaging the item responses, with higher scores reflecting higher psychopathy. The Chinese version of this measure has shown good psychometric characteristics (e.g., Huang et al., 2019). In the present study, Cronbach’ α was 0.75.

Data Analysis

First, descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations among variables were calculated. Second, we applied Model 4 of Hayes’s (2013) PROCESS macro to test the mediating role of psychopathy in linking childhood maltreatment and NSSI. The bias-corrected bootstrapping method based on 5000 samples was used to test the significance of the indirect effect, which was regarded as significant if the 95% confidence interval (CI) did not include zero.

Third, we applied Model 15 of the PROCESS macro to test the moderating effect of cognitive reappraisal on the relationship between childhood maltreatment and NSSI as well as on the relationship between psychopathy and NSSI. Finally, we calculated conditional indirect effects to further test whether the indirect effect of psychopathy in the relation between childhood maltreatment and NSSI varied under different values of cognitive reappraisal. All study variables were standardized in Model 4 and Model 15 before data analyses.

Given that age and classification of crimes were correlated with prisoners’ NSSI in previous research (e.g., Knight et al., 2017; Smith & Kaminski, 2010), we controlled these demographic variables in our statistical analyses. Age was treated as a continuous variable, while classification of crimes was treated as a dichotomous categorical variable. Classification of crimes was coded as 0 = non-violent crime and 1 = violent crime.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

In the present sample, 154 prisoners (14.8%) reported having engaged in at least one incidence of NSSI in the past year. Among the participants engaging in NSSI, 42.2% (n = 65) reported using only one method, and 57.8% (n = 89) reported using multiple methods of NSSI. Of the six methods, scratching the skin and self-burning were the most prevalent forms, reported by 8.0% (n = 83) of the participants. In addition, 6.2% (n = 65) of the participants reported banging the head, 6.0% (n = 62) stabbing the skin, 5.3% (n = 55) biting, and 3.2% (n = 33) self-cutting.

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, and correlations for the measured variables. As expected, childhood maltreatment, psychopathy, and NSSI were positively related to each other, and cognitive reappraisal showed negative correlations with childhood maltreatment, psychopathy, and NSSI, respectively. Moreover, age was negatively correlated with NSSI and psychopathy, and classification of crimes (0 = non-violent crime and 1 = violent crime) was positively associated with NSSI.

Testing for Mediation

Next, we tested the mediation effect of psychopathy in the association between childhood maltreatment and NSSI. As seen in Fig. 2, after controlling for age and classification of crimes, childhood maltreatment was positively associated with psychopathy (b = 0.30, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001), which in turn was positively related to NSSI (b = 0.17, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001). After taking into account the mediation effect of psychopathy, the residual direct effect of childhood maltreatment on NSSI was still significant (b = 0.31 SE = 0.03, p < 0.001). Results of bias-corrected bootstrapping with 5000 samples revealed a significant indirect effect (indirect effect = 0.05, SE = 0.01, 95% CI = [0.02, 0.08]), and the indirect effect accounted for 13.9% of the total effect (b = 0.36, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001) of childhood maltreatment on NSSI.

Testing for Moderated Mediation Effects

We examined whether cognitive reappraisal moderated the mediating effect of psychopathy in the relation between childhood maltreatment and NSSI. As shown in Fig. 3, after controlling for age and classification of crimes, the product (interaction term) of cognitive reappraisal and psychopathy (b = −0.13, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001), but not that of cognitive reappraisal and childhood maltreatment (b = 0.05, SE = 0.03, p > 0.05), was significantly associated with NSSI.

For descriptive purposes, we plotted predicted NSSI against psychopathy, separately for low (i.e., one SD below the mean) and high (i.e., one SD above the mean) levels of cognitive reappraisal (Fig. 4). Simple slopes analyses suggested that for prisoners with low skills in cognitive reappraisal, psychopathy significantly predicted NSSI (bsimple = 0.25, t = 6.62, p < 0.001). However, for prisoners high in cognitive reappraisal skills, the association between psychopathy and NSSI was not significant (bsimple = −0.01, t = −0.24, p > 0.05).

Finally, the test of the conditional indirect effect indicated that the indirect effect of psychopathy was significantly larger for prisoners with low cognitive reappraisal (indirect effect = 0.08, SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [0.04, 0.12]), than for those with high cognitive reappraisal (indirect effect = −0.00, SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [−0.04, 0.03]). The index of moderated mediation (Hayes, 2015) was −0.04 (SE = 0.01, 95% CI = [−0.07, −0.01]), indicating that cognitive reappraisal significantly weakened the indirect effect of psychopathy in the association between childhood maltreatment and NSSI.

Discussion

The current study extended previous research by proposing a moderated mediation model based on Nock’s (2009) integrated theoretical model of NSSI. The analyses on data from a male prison population indicated that psychopathy mediated the relationship between childhood maltreatment and NSSI, and the association between psychopathy and NSSI was stronger among those with low skills for cognitive reappraisal.

The first contribution of this study was the finding that 14.8% of the prisoners in our sample engaged in NSSI at least once in the past one year. This prevalence rate was higher than that reported in the UK (Hawton et al., 2014; Knight et al., 2017) and Belgium (Favril et al., 2018). The variability in the rates of self-harm during incarceration is likely to partly arise from heterogeneity across studies including: study populations, clarity of NSSI definition, measurement method or type of NSSI, length of study time period, and cultural differences between prison experiences (Knight et al., 2017; Vinokur & Levine, 2019). For example, in a sample of UK prisoners, NSSI was operationalized with a single question (i.e., “Since you have been in prison, have you deliberately harmed yourself in any way but not with the intention of killing yourself?”) that required a binary response (Knight et al., 2017). In another study on prisoners in the UK, Horton et al. (2018) used a different measurement method (i.e., a self-harm inventory) and found a higher rate of NSSI.

Another contribution of this study is that we found a direct link between childhood maltreatment and prisoners’ NSSI, as well as an indirect link by way of the mediating effect of psychopathy. The direct effect of childhood maltreatment on NSSI supports the integrated theoretical model of NSSI, in that NSSI may be a maladaptive outcome of early exposure to adverse environments (Nock, 2009). This finding is consistent with previous research showing that prisoners with a history of abuse or neglect during childhood were particularly vulnerable to NSSI while incarcerated (Favril et al., 2020; Lanes, 2009).

The evidence of statistical mediation suggests that psychopathy could serve as a “bridge” linking childhood maltreatment to prisoners’ NSSI. This may occur through two processes. On one hand, early traumatic experience as an environmental and biological stressor may lead to affective deficits, interpersonal deceptiveness, impulsiveness and antisocial tendencies (Krischer & Sevecke, 2008). On the other hand, prisoners who exhibit high psychopathy may display high levels of dysfunctional emotional processing and impaired self-control, and engage in NSSI to regulate the intensity of their emotions (Fadoir et al., 2019; Weiss et al., 2015; Yildirim & Derksen, 2015). Additionally, prisoners who exhibit high psychopathy may display high levels of pain tolerance and fearlessness about death, and use NSSI as a means of avoiding hurting someone else (Power et al., 2016). It’s worth noting that the indirect effect of psychopathy only accounted for 13.9% of the total effect of childhood maltreatment on NSSI, and the effect size of the mediation was relatively small. Further research should explore other mediators (e.g., high aversive emotions, poor communication skills) in the association between childhood maltreatment on NSSI (Nock, 2009).

Our results also showed that cognitive reappraisal moderated the relationship between psychopathy and NSSI. Specifically, psychopathy significantly increased the risk of NSSI among prisoners with low cognitive reappraisal skills, but did not affect NSSI among prisoners with high cognitive reappraisal skills. These results are similar to those of other studies that found that cognitive reappraisal buffered the associations between NSSI and stressful events (Voon et al., 2013), psychological distress (Voon et al., 2013) and dissociation (Navarro-Haro et al., 2015).

For prisoners with high psychopathy, a higher level of cognitive reappraisal may prevent the generation and misunderstanding of negative emotions, and decrease the use of NSSI for alleviating intense emotions (Gross & John, 2003). Cognitive reappraisal may also make prisoners more likely to choose adaptive methods that bring about long-term benefits (Fritz, 2020). By contrast, prisoners low in cognitive reappraisal have difficulties in drawing attention away from impulsive thoughts and dysregulated emotions, and they are more likely to resort to NSSI as a convenient means of obtaining immediate rewards (e.g., pressure release, emotion regulation; Navarro-Haro et al., 2015).

Contrary to our expectations, cognitive reappraisal did not moderate the direct effect of childhood maltreatment on NSSI. It is possible that the negative emotions associated with childhood maltreatment are so overwhelming that cognitive reappraisal is not effective as a coping strategy. Research has shown that people are likely to use disengagement and distraction to regulate high-intensity negative situations, whereas they are likely to use cognitive reappraisal to regulate emotions in low-intensity negative situations (Sheppes et al., 2011). A recent study also documented that both younger and older men preferred distraction over reappraisal when regulating high-intensity emotion (Martins et al., 2018).

Limitations, Future Directions, and Implications

The current study has some limitations, leaving opportunities for future research. First, the measurement of NSSI and childhood maltreatment in our study relied on participants’ retrospective reports. NSSI is a stigmatized and socially unacceptable behavior (Ross & Heath, 2002), so prisoners’ retrospective accounts may be subjective and unreliable. Future studies can use ecological momentary assessment (ECA) to acquire real-time descriptions of the phenomenology of self-injury (Klonsky, 2007). For the assessment of childhood maltreatment, the records of Child Protective Services (CPS) are a more objective measure for capturing potentially sensitive issues (Shaffer et al., 2008). Second, the sample was not representative of the prison population, as it was limited to males from two Chinese prisons. Given that gender and culture were associated with prisoners’ NSSI in previous research (e.g., Knight et al., 2017), further studies are needed to test whether the findings can be generalized to female prisoners, prisoners in different prison conditions, and prisoners in other countries. Third, we have drawn on Nock’s theoretical framework and therefore discussed the role of NSSI functions, yet these were not measured in the study. Future studies should use established and comprehensive psychometric measures (e.g., ISAS; Klonsky & Glenn, 2009) to identify specific reasons for NSSI in prisoners (Gardner et al., 2016).

The fourth limitation is related to the measurement of psychopathy. The Dirty Dozen (DD) is a concise and efficient measure of the Dark Triad construct (i.e., psychopathy, narcissism, and Machiavellianism). However, the DD Psychopathy subscale does not assess certain traits believed to be central to psychopathy, such as interpersonal antagonism and disinhibition. This limited coverage may reduce the subscale’s convergent validity with other measures of psychopathy (Miller et al., 2012). Future research should use other more comprehensive measures of psychopathy (e.g., the Psychopathy Checklist—Revised, PCL-R) to test the role of prisoners’ psychopathy in the association between childhood maltreatment and NSSI. Finally, our findings were based on cross-sectional data, which provide only correlational evidence for the hypothesized relationships. To demonstrate causal relationships between childhood maltreatment and NSSI that are mediated by psychopathy, future research should be based on longitudinal data or take the form of clinical intervention studies.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the results from our study have at least two practical implications for the prevention and treatment of NSSI among prisoners. On one hand, our findings highlight the adverse effects of childhood maltreatment and psychopathy on prisoners’ NSSI. The implementation of a screening process that is specific to self-harm (e.g., adverse childhood experiences, personality disorder such as psychopathy) may contribute to an increased awareness of self-harm and mental health issues among prison staff. Previous research has pointed out that an improvement in staff awareness and attitude, along with further training, is useful for the early prevention of NSSI in prisons (Hawton et al., 2014).

On the other hand, strategies for teaching cognitive reappraisal skills to prisoners may be effective in interventions designed to reduce NSSI. In light of this finding, therapies focusing on cognitive restructuring, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, may provide a useful treatment option for early intervention (Andrews et al., 2013). A recent evaluation of cognitive reappraisal interventions reported significant reductions in NSSI urges and acts (Bentley et al., 2017).

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Andrews, T., Martin, G., Hasking, P., & Page, A. (2013). Predictors of continuation and cessation of nonsuicidal self-injury. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53, 40–46.

Bentley, K. H., Nock, M. K., Sauer-Zavala, S., Gorman, B. S., & Barlow, D. H. (2017). A functional analysis of two transdiagnostic, emotion-focused interventions on nonsuicidal self-injury. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85, 632–646.

Bernstein, D. P., Stein, J. A., Newcomb, M. D., Walker, E., Pogge, D., Ahluvalia, T., Stokes, J., Handelsman, L., Medrano, M., Desmond, D., & Zule, W. (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the childhood trauma questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27, 169–190.

Blair, R. J. R., Colledge, E., Murray, L., & Mitchell, D. G. V. (2001). A selective impairment in the processing of sad and fearful expressions in children with psychopathic tendencies. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 29, 491–498.

Campbell, M. A., Porter, S., & Santor, D. (2004). Psychopathic traits in adolescent offenders: An evaluation of criminal history, clinical, and psychosocial correlates. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 22, 23–47.

Carli, V., Jovanović, N., Podlešek, A., Roy, A., Rihmer, Z., Maggi, S., Marusic, D., Cesaro, C., Marusic, A., & Sarchiapone, M. (2010). The role of impulsivity in self-mutilators, suicide ideators and suicide attempters-a study of 1265 male incarcerated individuals. Journal of Affective Disorders, 123, 116–122.

Carli, V., Mandelli, L., Postuvan, V., Roy, A., Bevilacqua, L., Cesaro, C., et al. (2011). Self-harm in prisoners. CNS Spectrums, 16, 75–81.

DeHart, D. D., Smith, H. P., & Kaminski, R. J. (2009). Institutional responses to self-injurious behavior among inmates. Journal of Correctional Health Care, 15, 129–141.

Fadoir, N. A., Lutz-Zois, C. J., & Goodnight, J. A. (2019). Psychopathy and suicide: The mediating effects of emotional and behavioral dysregulation. Personality and Individual Differences, 142, 1–6.

Favril, L. (2019). Non-suicidal self-injury and co-occurring suicide attempt in male prisoners. Psychiatry Research, 276, 196–202.

Favril, L., Baetens, I., & Vander Laenen, F. (2018). Zelfverwondend gedrag in detentie: Prevalentie, risicofactoren en preventie [non-suicidal self-injury among prisoners: Prevalence, risk factors, and prevention]. Tijdschrift voor Psychiatrie, 60, 808–816.

Favril, L., Yu, R., Hawton, K., & Fazel, S. (2020). Risk factors for self-harm in prison: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7, 682–691.

Ford, K., Bellis, M. A., Hughes, K., Barton, E. R., & Newbury, A. (2020). Adverse childhood experiences: A retrospective study to understand their associations with lifetime mental health diagnosis, self-harm or suicide attempt, and current low mental wellbeing in a male welsh prison population. Health & justice, 8, 13.

Fritz, H. L. (2020). Why are humor styles associated with well-being, and does social competence matter? Examining relations to psychological and physical well-being, reappraisal, and social support. Personality and Individual Differences, 154, 109641.

Gardner, K. J., Dodsworth, J., & Klonsky, E. D. (2016). Reasons for non-suicidal self-harm in adult male offenders with and without borderline personality traits. Archives of Suicide Research, 20, 614–634.

Graham, N., Kimonis, E. R., Wasserman, A. L., & Kline, S. M. (2012). Associations among childhood abuse and psychopathy facets in male sexual offenders. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 3, 66–75.

Gratz, K. L., & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26, 41–54.

Gross, J. J. (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology, 2, 271–299.

Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 348–362.

Gu, H., Ma, P., & Xia, T. (2020). Childhood emotional abuse and adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury: The mediating role of identity confusion and moderating role of rumination. Child Abuse & Neglect, 106, 104474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104474

Hasking, P., Whitlock, J., Voon, D., & Rose, A. (2017). A cognitive-emotional model of NSSI: Using emotion regulation and cognitive processes to explain why people self-injure. Cognition and Emotion, 31, 1543–1556.

Hauber, K., Boon, A., & Vermeiren, R. (2019). Non-suicidal self-injury in clinical practise. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 502.

Hawton, K., Linsell, L., Adeniji, T., Sariaslan, A., & Fazel, S. (2014). Self-harm in prisons in England and Wales: An epidemiological study of prevalence, risk factors, clustering, and subsequent suicide. Lancet, 383, 1147–1154.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. The Guilford Press.

Hayes, A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50, 1–22.

Hofmann, S. G., Heering, S., Sawyer, A. T., & Asnaani, A. (2009). How to handle anxiety: The effects of reappraisal, acceptance, and suppression strategies on anxious arousal. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47, 389–394.

Horton, M. C., Dyer, W., Tennant, A., & Wright, N. M. J. (2018). Assessing the predictability of self-harm in a high-risk adult prisoner population: A prospective cohort study. Health & justice, 6, 18.

Huang, N., Zuo, S., Wang, F., Cai, P., & Wang, F. (2019). Environmental attitudes in China: The roles of the dark triad, future orientation and place attachment. International Journal of Psychology, 54, 563–572.

Jaffee, S. R. (2017). Child maltreatment and risk for psychopathology in childhood and adulthood. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 13, 525–551.

Jonason, P. K., & Webster, G. D. (2010). The dirty dozen: A concise measure of the dark triad. Psychological Assessment, 22, 420–432.

Klonsky, E. D. (2007). The functions of deliberate self-injury: A review of the evidence. Clinical Psychology Review, 27, 226–239.

Klonsky, E. D., & Glenn, C. R. (2009). Assessing the functions of nonsuicidal self-injury: Psychometric properties of the inventory of statements about self-injury (ISAS). Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 31, 215–219.

Klonsky, E. D., Oltmanns, T. F., & Turkheimer, E. (2003). Deliberate self-harm in a nonclinical population: Prevalence and psychological correlates. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 160, 1501–1508.

Klosowska, J., Prochwicz, K., & Kaluzna-Wielobob, A. (2019). The relationship between cognitive reappraisal strategy and skin picking behaviours in a non-clinical sample depends on personality profile. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, 21, 129–137.

Knight, B., Coid, J., & Ullrich, S. (2017). Non-suicidal self-injury in UK prisoners. International Journal of Forensic MentalHealth, 16, 172–182.

Krischer, M. K., & Sevecke, K. (2008). Early traumatization and psychopathy in female and male juvenile offenders. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 31, 253–262.

Lanes, E. (2009). Identification of risk factors for self-injurious behavior in male prisoners. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 54, 692–698.

Liu, R. T., Scopelliti, K. M., Pittman, S. K., & Zamora, A. S. (2018). Childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 5, 51–64.

Lobbestael, J., van Teffelen, M., & Baumeister, R. F. (2020). Psychopathy subfactors distinctively predispose to dispositional and state-level of sadistic pleasure. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 67, 101458.

Madjar, N., Segal, N., Eger, G., & Shoval, G. (2019). Exploring particular facets of cognitive emotion regulation and their relationships with nonsuicidal self-injury among adolescents. Crisis, 40, 280–286.

Martins, B., Sheppes, G., Gross, J. J., & Mather, M. (2018). Age differences in emotion regulation choice: Older adults use distraction less than younger adults in high-intensity positive contexts. Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 73, 603–611.

Miller, J. D., Few, L. R., Seibert, L. A., Watts, A., & Lynam, D. R. (2012). An examination of the dirty dozen measure of psychopathy: A cautionary tale about the costs of brief measures. Psychological Assessment, 24, 1048–1053.

Navarro-Haro, M. V., Wessman, I., Botella, C., & García-Palacios, A. (2015). The role of emotion regulation strategies and dissociation in non-suicidal self-injury for women with borderline personality disorder and comorbid eating disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 63, 123–130.

Nock, M. K. (2009). Why do people hurt themselves? New insights into the nature and functions of self-injury. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18, 78–83.

Nock, M. K., & Prinstein, M. J. (2004). A functional approach to the assessment of self-mutilative behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 885–890.

Peh, C. X., Shahwan, S., Fauziana, R., Mahesh, M. V., Sambasivam, R., Zhang, Y. J., Ong, S. H., Chong, S. A., & Subramaniam, M. (2017). Emotion dysregulation as a mechanism linking child maltreatment, exposure, and self-harm behaviors in adolescents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 67, 383–390.

Power, J., Smith, H. P., & Beaudette, J. N. (2016). Examining Nock and Prinstein’s four-function model with offenders who self-injure. Personality Disorders-Theory Research and Treatment, 7, 309–314.

Robinson, K., Garisch, J. A., Kingi, T., Brocklesby, M., Angelique, O. C., Langlands, R. L., Russell, L., & Wilson, M. S. (2019). Reciprocal risk: The longitudinal relationship between emotion regulation and non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 47, 325–332.

Roe-Sepowitz, D. (2007). Characteristics and predictors of self-mutilation: A study of incarcerated women. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 17, 312–321.

Ross, S., & Heath, N. (2002). A study of the frequency of self-mutilation in a community sample of adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 31, 67–77.

Shaffer, A., Huston, L., & Egeland, B. (2008). Identification of child maltreatment using prospective and self-report methodologies: A comparison of maltreatment incidence and relation to later psychopathology. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32, 682–692.

Sheppes, G., Scheibe, S., Suri, G., & Gross, J. J. (2011). Emotion-regulation choice. Psychological Science, 22, 1391–1396.

Smith, H. P., & Kaminski, R. J. (2010). Inmate self-injurious behaviors: Distinguishing characteristics within a retrospective study. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 37, 81–96.

VandenBos, G. R. (2013). APA dictionary of clinical psychology. American Psychological Association.

Vinokur, D., & Levine, S. Z. (2019). Non-suicidal self-harm in prison: A national population-based study. Psychiatry Research, 272, 216–221.

Voon, D., Hasking, P., & Martin, G. (2013). The roles of emotion regulation and ruminative thoughts in non-suicidal self-injury. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 53, 95–113.

Voon, D., Hasking, P., & Martin, G. (2014a). Emotion regulation in first episode adolescent non-suicidal self-injury: What difference does a year make? Journal of Adolescence, 37, 1077–1087.

Voon, D., Hasking, P., & Martin, G. (2014b). Change in emotion regulation strategy use and its impact on adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury: A three-year longitudinal analysis using latent growth modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 123, 487–498.

Weiss, N. H., Sullivan, T. P., & Tull, M. T. (2015). Explicating the role of emotion dysregulation in risky behaviors: A review and synthesis of the literature with directions for future research and clinical practice. Current Opinion in Psychology, 3, 22–29.

Wolff, J. C., Thompson, E., Thomas, S. A., Nesi, J., Bettis, A. H., Ransford, B., Scopelliti, K., Frazier, E. A., & Liu, R. T. (2019). Emotion dysregulation and non-suicidal self-injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Psychiatry, 59, 25–36.

Yildirim, B. O., & Derksen, J. J. (2015). Clarifying the heterogeneity in psychopathic samples: Towards a new continuum of primary and secondary psychopathy. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 24, 9–41.

Zhao, Y., & Zhao, G. (2015). Emotion regulation and depressive symptoms: Examining the mediation effects of school connectedness in Chinese late adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 40, 14–23.

Funding

This research was funded by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (2021JJ40336) and the Scientific Research Foundation of Hunan Provincial Education Department (19C1148).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gu, H., Xia, T. & Wang, L. Childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury in prisoners: the mediating role of psychopathy and moderating role of cognitive reappraisal. Curr Psychol 42, 8963–8972 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02213-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02213-5