Abstract

To date, the majority of research studying lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) health has been conducted in Westernized, predominantly individualistic countries. Building on minority stress theory and models of LGBTQ health, we explored how sexual orientation and nationality moderated the association between internalized heterosexism and life satisfaction for lesbian and bisexual (LB) women living in two countries (Turkey and Belgium) with contrasting social contexts. The results of two-way MANOVA, in a sample of 339 Turkish and 220 Belgian LB women, revealed main effects but no interaction effects. LB women in Belgium reported less internalized heterosexism and more life satisfaction than LB women in Turkey. The results of moderation analyses indicated no moderation effect, however internalized heterosexism and country emerged as the best predictors of life satisfaction. Findings were interpreted with a focus on how culture-specific aspects contribute to life satisfaction among LB women. Our findings suggest mental health professionals working with LB women need to tailor therapeutic interventions to reflect the social context connected to their patients’ nationality, in order to effectively address internalized heterosexism, improve life satisfaction, and promote self- and social advocacy. Cultural values, such as adherence to collectivistic or individualistic norms, should be included as variables in future research examining determinants of LGBTQ health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Health disparities for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (LGBTQ) individuals persist across the globe, largely due to the continued discrimination towards and lack of legal protections for LGBTQ identities (World Health Organization [WHO], 2016). Accounting for the role of social pressures and dynamics, such as difficulty accessing health care service and experiences of violence, in the lived health experiences of LGBTQ populations is considered best practice in research and mental healthcare (Mink et al., 2014; WHO, 2016). The perspective that LGBTQ people face discrimination, unique courses of lifespan development, intersecting and compounding stressors relative to other social identifies (gender, ethnicity), and that these experiences result in health disparities are all components of minority stress theory (Meyer, 2003). Building off minority stress theory, issues of culture and the relative stigma associated with LGBTQ identities remain critical when conceptualizing the health needs of LGBTQ people across the globe (Mink et al., 2014; WHO, 2016).

Minority Stress

Minority stress can be conceptualized as distal or external to individuals (e.g., discrimination in the social environment), and as proximal or internal (e.g., internalized prejudice) (Meyer, 2003). LGBTQ-specific stressors that arise from distal and external factors in the social context include stigma, family rejection, social isolation, guilt and shame, poorly developed interpersonal skills, mental health concerns, and gender role stress (Mink et al., 2014). Minority stress experiences can be both subtle and overt, including the anticipation of discrimination and the internalization of prejudicial values relative to gender and sexual orientation diversity. These cognitive and behavioral responses compound the effects of anti-LGBTQ biases in society on LGBTQ health, creating a circular effect where poor outcomes, in turn, influence future stressors (Khan et al., 2017). Minority stress also can be conceptualized as proximal stress, also known as internalized prejudice or heterosexism.

Internalized Heterosexism

Internalized heterosexism, or the degree that negative social stigma, biases and prejudices towards lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) people are accepted as true by individuals in LGB communities (Meyer, 2003). Internalized heterosexism, turning societal devaluation of LGB identities inward, has been studied widely in the literature as a correlate of health outcomes (Berg et al., 2016; Newcomb & Mustanski, 2010). Non-affirming environments are correlated with higher rates of internalized heterosexism (Barnes & Meyer, 2012; Chow & Cheg, 2010; Szymanski & Sung, 2013), and in turn, increased internalized heterosexism is associated with psychological distress (Newcomb & Mustanski, 2010) and negative mental health outcomes such as depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation for LGB individuals (McLaren, 2016).

The Relationship between Internalized Heterosexism and Life Satisfaction

The Relationship between Internalized Heterosexism and Resiliency Factors, Such as Life Satisfaction, Appears to Support an Inverse Relationship between the Two Constructs. Michaels et al. (2019) Identified that as Heterosexist Discrimination Increases, Individuals’ Level of Internalized Heterosexism Also Increases, and as a Result their Feelings of Satisfaction with Life Decrease. In a Parallel Finding, Öztürk and Kındap (2011) Found that as LGB People Internalize society’s Negative Judgments, Attitudes, and Assumptions towards LGB Individuals, their Life Satisfaction Decreases. Research Indicated that Social Policies (E.G., more Inclusive Rights Regarding Sexual Orientation) Could Effectively Mitigate Minority Stress and Improve Life Satisfaction (Berggen et al., 2018; Traeen et al., 2009; Wong & Tang, 2003). Although it Seems Intuitive that LGB People Living in a more Inclusive Society, Such as Belgium, Would Experience less Internalized Heterosexism and Increased Life Satisfaction than LGB People Living in Oppressive Societies like Turkey, no Research Exists to Date that Directly Assesses the Relationship between these Constructions for LGB Individuals Living in Divergent Types of Societies

Intersectionality

LGBTQ individuals are situated in their predominant culture, which privileges certain social identities while diminishing others, and thus are impacted by social discourses, institutional and governmental policies, and legal protections (or lack thereof) towards LGBTQ identities. LGBTQ individuals living in heteronormative cultures are likely to experience higher levels of stigma and stress, and thus worsened health outcomes (Mink et al., 2014; Newcomb & Mustanski, 2010). Further, LGBTQ stigma, discrimination, and prejudice interacts and intersects with other societal advantages or disadvantages, such as race, ethnicity, culture, geography, gender, religion, ability, and age (Mink et al., 2014; WHO, 2016). As such, the paradigm of intersectionality is appearing more in the literature, with a focus on LGBTQ people of color in the United States being a welcome addition to scholarly efforts over the past decade (e.g., Barnett et al., 2019). Proponents of intersectionality encourage scholars to conceptualize the needs of sub-groups within social categories, and how individuals’ needs manifest through the inhabitation of multiple salient identity statuses (e.g., being LGBTQ, a person of color, and an immigrant). The term LGBTQ encompasses a diverse group of identities and communities who may encounter differences in stress and stigma based on their intersections with other identities. One of the main goals of the present study was to explore how the social advantages or disadvantages of other identities, namely gender and nationality, intersect with sexual-affectional orientation to influence life satisfaction for lesbian and bisexual (LB) women.

Intersectionality of Sexual-Affectional Orientation with Gender

As a result of intersectionality, LB women’s experiences are dissimilar from that of gay and bisexual (GB) men (McCarn & Fassinger, 1996; Özbay & Soydan, 2003; Rich, 1980; Szymanski & Chung, 2003). LB women have at least two minority statuses in most countries, as women in patriarchal cultures and as LB women in heteronormative societies, augmenting minority stress (Szymanski & Kashubeck-West, 2008). LB women who internalize patriarchal and heteronormative messages from the dominant discourses and who encounter sexist and heterosexist events tend to experience increased psychological distress (Szymanski, 2005; Szymanski & Hendrichs-Beck, 2013; Szymanski & Kashubeck-West, 2008; Szymanski & Owens, 2008). How gender and sexual identity intersect to influence the experience of life satisfaction, mental health and well-being for LB women is poorly understood, and little to no scholarship exists that also factors in the influence of nationality or other social context variables.

Moreover, the experiences of bisexual individuals differ from those of lesbian women and gay men. In addition to heterosexism, bisexual individuals encounter monosexism, prejudice against bisexuality that is the result of the normative binary conceptualization of sexuality (Pennasilico & Amodeo, 2019). This may result in bi-erasure, in which bisexuality is rendered invisible or delegitimized, leading to the marginalization of bisexuals even among LGBTQ communities (Ross et al., 2018). As an example of binegativity, a study with Turkish youth found that bisexuals were perceived more negatively than gay and lesbian persons and were described as “insatiable, indecisive, incoherent, non-selective, uncertain about their desires, immature, illogical, unbalanced, tasteless, and greedy” (Şah, 2011, p. 94). Further, in a meta-analysis of studies that compared the mental health outcomes of bisexuals to gay and lesbian, bisexuals exhibit higher rates of depression and anxiety, which the researchers link to the experiences of binegativity and bi-erasure (Ross et al., 2018). Hence, we hypothesize bisexual women would report more internalized heterosexism and decreased life satisfaction as compared to lesbian women.

Intersectionality of Sexual-Affectional Orientation and Nationality

Nationality is another aspect of intersectionality that impacts the lived experiences of LGBTQ individuals, as LGBTQ social discourses are shaped by the country in which people reside and attitudes towards LGBTQ people vary widely from country to country across the world (Poushter & Kent, 2020). Few studies, however, have compared the social and health experiences of LGBTQ individuals living in societies with divergent cultural norms. The researchers who have studied cultural factors in LGBTQ populations have found that LGBTQ life satisfaction is moderated or mediated by racial, ethnic, and acculturation factors (Fragoso & Kashubeck, 2000; Lange, 2010; Liu & Iwamoto, 2006; Norwalk et al., 2011). An unsurprising conclusion from these studies is LGBTQ individuals living in countries with more cultural discrimination towards LGBTQ identities tend to demonstrate lower life satisfaction.

Although acceptance towards LGBTQ people varies greatly from nation to nation (Poushter & Kent, 2020), the majority of scholarship involving LGBTQ persons and minority stress is located in Western(−ized) populations, such as in the United States and Europe (Berg et al., 2016). Westernized countries tend to be more individualistic, wealthier, and also increasingly accepting of LGBTQ people (Poushter & Kent, 2020). Hence, more research is needed on how nationality impacts the experiences and health outcomes for LGBTQ individuals, in order to effectively address the health needs of LGBTQ people living in varying social contexts. After reviewing international data on LGBTQ rights, acceptance, and legal protections around the world, we chose two countries, the collectivistic transcontinental country of Turkey and the individualistic Western European country of Belgium, in which we could access participants.These two countries were specifically selected due to (a) the divergent degrees of interdependence among members in each country (i.e., collectivism-individualism); (b) the contrasting social discourses on the affirmation of LGBTQ people in their societies; and (c) the opposing government and legal policies towards LGBTQ individuals in each country .

Comparing the Social Context of Turkey & Belgium

According to the Hofstede model of national cultures (Hofstede, 2011), which identifies and rates six dimensions of cultures, Turkish society has more collectivist tendencies compared to Belgium society. Collectivistic cultures, such as Turkey, promote values of group harmony, mutual obligation, sacrifice for the common good, and duty to one’s family, community, and society, whereas individualistic cultures like Belgium prioritize the values of individual rights, personal autonomy, self-expression, freedom of choice, and self-fulfillment (Oyserman et al., 2002). Further, Turkey is a highly religious country with 99% of the population identifying as Muslim; in Belgium, 50% of the population identifies as Roman Catholic, with the majority of the remaining population identifying as either atheist (9%) or having no religious affiliation (32%) (Central Intelligence Agency, 2021).

The two societies also differ in terms of acceptance, affirmation, and inclusion towards LGBTQ people. According to the current Rainbow Index published by the European Region of the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA-Europe, 2020), Belgium ranks 2nd out of 49 European countries in terms of respect of LGBTQ rights and equality, whereas Turkey ranks 48th. In a Pew Research Center survey conducted in 2019, only 25% of Turkish individuals reported they were accepting of homosexuality (Poushter & Kent, 2020). Although survey data was not collected in Belgium, over 86% of individuals residing the surveyed surrounding countries of the Netherlands, Germany, the United Kingdom, and France reported acceptance of homosexuality (Poushter & Kent, 2020). The laws and policies regarding the rights of LGBTQ people are also quite different between Belgium and Turkey (Dewaele et al., 2009; Göçmen & Yılmaz, 2017). Same-sex marriage is not recognized in Turkey, sexual orientation is not included in the equality articles of the Turkish constitution, and Turkey lacks legal arrangements to prevent and punish hate speech and crimes against LGBTQ people (Engin, 2015; Göçmen & Yılmaz, 2017; Öztürk, 2011). In contrast, the LGBTQ rights movement in Belgium began in the 1950s and has made significant progress towards decreasing the institutional oppression of LGBTQ Belgians (Borghs, 2016). Belgium has recognized same-sex marriage since 2003 and has permitted LGBTQ couples to adopt children since 2006. Belgium also includes sexual orientation as a protected status in their employment and housing discrimination laws (Equaldex, 2019).

The Current Study

The literature indicates that LGB individuals’ experiences of internalized heterosexism and life satisfaction may differ in various social contexts, reflective of societal and institutional discrimination towards LGB identities that are ingrained in daily practices (Chow & Cheg, 2010; Szymanski & Sung, 2013). Minority stress theory suggests that heterosexist discrimination and internalized heterosexism are related uniquely to greater psychological distress and lower life satisfaction among LGB individuals (Meyer, 2003). Previous research has indicated that internalized heterosexism and heterosexism were related to psychological distress in lesbians and bisexuals (Szymanski & Kashubeck-West, 2008; Szymanski & Owens, 2008). Furthermore, social advantages or disadvantages from other identities, such as gender and geography, interact with sexual-affectional orientation in contributions to LGB health outcomes (Mink et al., 2014; WHO, 2016). As such, McCormick-Huhn et al. (2019) encouraged psychologists to adopt intersectional thinking to understand different causal mechanisms underlying experiences of stress and stigma within a social, structural, and cultural context (i.e., marriage equality law for sexuality minorities). At this point, because of the different reflection of societal, historical, and institutional practices related to LGBTQ human rights in Turkey and Belgium, we believe investigating the influence of internalized heterosexism on life satisfaction in these two countries will contribute to the literature and our understanding of how nationality impacts the lived experiences and health outcomes of LGB individuals.

Our first aim was to explore how internalized heterosexism and life satisfaction differ with regard to social contexts defined by sexual orientation (i.e., lesbians and bisexual) and nationality (i.e., Turkey and Belgium) for LB women. Based on the literature which suggests LGBTQ individuals who live in more heteronormative cultures experience lower life satisfaction (Fragoso & Kashubeck, 2000; Lange, 2010; Liu & Iwamoto, 2006; Norwalk et al., 2011), and the data that demonstrates Turkey as a significantly less accepting country towards LGBTQ people as compared to Belgium, our first hypothesis is:

-

Hypothesis 1. LB women in Turkey experience greater internalized heterosexism and lower life satisfaction than LB women in Belgium.

The literature also indicates that bisexual women may differ from lesbian women in internalized heterosexism and life satisfaction (Hayfield et al., 2014; Newcomb & Mustanski, 2010); however, we have no evidence regarding how LB women in Turkey and Belgium will differ in internalized heterosexism and life satisfaction. Thus, the second research hypothesis is: Hypothesis 2. Bisexual women experience greater internalized heterosexism and lower life satisfaction than lesbian women.

The literature contains scholarship that documents how internalized heterosexism is negatively related to life satisfaction (i.e., Michaels et al., 2019). This link, however, has not been specifically researched with LB women from Turkey and Belgium. Moreover, the literature lacks a description of how varying sexual orientation identities and social context, as defined in this study by nationality, affect the established negative correlation between internalized heterosexism and life satisfaction. Thus, we investigated how sexual orientation and nationality moderates the association of internalized heterosexism and life satisfaction. Based on this purpose, we hypothesized:

-

Hypothesis 3. Internalized heterosexism is negatively associated to life satisfaction.

-

Hypothesis 4. Nationality and sexual orientation moderates the association between internalized heterosexism on life satisfaction.

The proposed moderated-mediation in hypothesis four is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Method

Data Collection Procedure

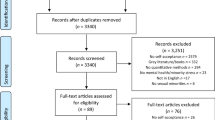

After obtaining approval for this research from the [university’s name] Human Participants Ethics Committee, we collected data through a purposeful sampling procedure via an online survey. A total of 100 different LGBTQ, feminist, and queer organizations in Turkey (60 organizations such as Kaos GL, Lambda Istanbul, Keskesor LGBTI, Lezbiyen Biseksuel Feministler, Lezbiyen Dayanisma Agi, LGBT Turkiye, Turkiye LGBTI Birligi, Bogazici Universitesi LGBTI+ Calismalari Klubu, Genc LGBTI Dernegi Izmir, etc.) and Belgium (40 organizations such as Rainbow House, Cheff, Tels quells, Egow, Brussels Women Munch, L-Tour, Rainbow Free Hand, Activ LGBT, etc.) were contacted to announce the present study to their members. Most of these organizations publicized the study on their social media accounts, and some sent the survey to their e-mail lists several times throughout the data collection process. The completion of the questionnaires took about 20–25 min (Fig. 2).

Data Collection Instruments

Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS)

The SWLS (Diener et al., 1985) is a five-item scale that measures general life satisfaction. Items are measured on a 7-point Likert-type scale with response options ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Total scores on the scale can range from 5 to 35, and higher scores reflect greater life satisfaction. A sample item includes “If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing.” Factor analysis for the original scale revealed a single-factor solution with an internal consistency coefficient of .87 and a two-month test-retest reliability coefficient of .82 (Diener et al., 1985). In the current study, we used the total score of the SWLS, and the reliability coefficients for Turkish and Belgian versions were .89 and .87, respectively.

Bisexual Adapted-Lesbian Internalized Homophobia Scale (BA-LIHS)

The original LIHS is a 52-item scale designed to measure the internalized heterosexism of lesbians only (Szymanski & Chung, 2001) and consists of five subscales: Personal feelings about being a lesbian, connection with the lesbian community, public identification as a lesbian, attitudes towards other lesbians, and moral and religious attitudes toward lesbianism. Responses were scored on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The alpha coefficients for internal consistency and test-retest reliabilities were reported as .94 and .93, respectively (Szymanski & Chung, 2001) for the lesbian version.

In the current study, we used a modified bisexual inclusive version of the LIHS (Balsam & Szymanski, 2005). In the BA-LIHS, an original sample item “If my peers knew of my lesbianism, I am afraid that many would not want to be friends with me,” was modified to “If my peers knew of my lesbianism or bisexuality, I am afraid that many would not want to be friends with me.” The factor structure, number of items loaded onto each factor, and scoring remained the same as in the original lesbian version of the LIHS. The alpha for internal consistency of the BA-LIHS was computed as .89 (Balsam & Szymanski, 2005). We used the total score of the BA-LIHS, and the alphas were computed as .73 and .74 for the Turkish and Belgian versions, respectively.

Participants

The Turkish sample consisted of 339 participants (Mage = 26.51; SDage = 6.23; rangeage = 18 to 50), of which 119 (35.1%) identified as lesbian and 220 (64.9%) identified as bisexual. The Belgian sample consisted of 220 participants (Mage = 29.31; SDage = 8.73; rangeage = 18 to 62). Of the participants from Belgium, 130 (59.1%) identified as lesbian and 90 (40.9%). as bisexual. Contrary to women in Belgium (59.1% lesbian; 40.9% bisexual), more women in Turkey identified as bisexual (64.9%) than lesbian (35.1%), χ2(1, n = 559) = 31.08, p < .001, Φ = .236.

All participants included in the study identified as cisgender. The majority of participants identified with a lower to lower-middle socioeconomic status and as non-religious. Of the participants from Turkey, 212 (62.5%) had a monthly income between 0 and 2000 Turkish Liras, and188 (85.5%) Belgian participants had a monthly income between 0 and 2000 Euros (85.5%).Footnote 1 Of Turkish participants, 187 (55.2%) identified as non-religious, and for Belgian participants, 145 (65.9%) identified as non-religious.

Data Analysis

Initially, to demonstrate the associations among study variables, we carried out correlation analyses across cultural identities. Then, we conducted a two-way MANOVA to test our first and second hypotheses. Finally, we did a moderation analysis via PROCESS (Model 2, Hayes, 2018, 3.5), an add-on macro for SPSS 28, to test our third and fourth hypotheses. In Model 2, the conditional effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable is explored as a function of two moderators. In our context, we tested the association between internalized heterosexism and life satisfaction as a function of sexual orientation (1 = lesbian; 2 = bisexual women) and social context (1 = Belgium; 2 = Turkey). We tested the model using 10,000 bootstrap samples.

Results

Correlation Analysis

The results of correlation analyses, computed independently for Belgian and Turkish samples, are displayed in Table 1. For participants from Belgium, internalized heterosexism was negatively related to life satisfaction, r = −.16, p < .05. There was no correlation between the two for Turkish participants r = .01, p > .05. All the remaining correlations appeared non-significant in both countries.

Two-Way MANOVA

Next, we conducted a two-way MANOVA to explore how life satisfaction and internalized heterosexism differed with regard to sexual orientation (i.e., lesbians vs. bisexual) and social context based on nationality (i.e., Turkey vs. Belgium) with the General Linear Modeling analysis of SPSS 18. Prior to the analyses, we checked assumptions. Only completed cases were included in the analyses; therefore, missing data was not an issue for the current study. We chose a multivariate approach to control the Type I error (Hair Jr. et al., 2013). To handle the violations of equality of variances and multivariate normality, we set a more conservative p (.01 instead of .05) for significance testing and interpreted Pillai’s trace instead of Wilks’s lambda, a more robust statistic for comparison, respectively (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007).

As illustrated in Table 2, the results of the two-way MANOVA indicated no interaction effect, F(2, 554) = .56, p = .56, Pillai’s trace = .00, η2 = .00, but did show main effects. Nationality yielded a statistically significant difference in the combined dependent variables, F (2, 554) = 77.41, p < .001, Pillai’s trace = .22, η2 = .22, accounting for 22% of multivariate variance. The results of univariate ANOVAs revealed differences both in life satisfaction, F (1, 555) = 50.96, p < .001, η2 = .08, and internalized heterosexism, F (1, 555) = 111.30, p < .001, η2 = .17, only for nationality. Compared to lesbians and bisexual women in Turkey, lesbian and bisexual women in Belgium reported more life satisfaction (M = 23.75, SD = 5.54 vs. M = 19.75, SD = 6.75) and less internalized heterosexism (M = 199.36, SD = 19.37 vs. M = 201.20 SD = 20.86). Thus, our first hypothesis was supported.

Further, lesbians and bisexual women significantly differed on the combined dependent variables, F (2, 554) = 3.03, p = .049, Pillai’s trace = .01, η2 = .01. Sexual orientation, however, accounted for only 1% of the multivariate variance. Univariate Analyses of Variance (ANOVAs; Table 2) indicated that lesbian and bisexual women did not differ on life satisfaction and internalized heterosexism. Thus, the results did not support our second hypothesis.

Moderation Analysis

The results of moderation analyses revealed that the overall model was significant, R2 = .11; F(5, 553) = 13.324; p < .001). Internalized heterosexism (β = −.146; SE = .066; 95% CI = −.275, −.016) and nationality (β = −14.368; SE = 5.934; 95% CI = −26.024, −2.712) emerged as the single predictors of life satisfaction. Participants with higher internalized heterosexism scores reported lower life satisfaction. Thus, our third hypothesis was supported. Similarly, LB women in Turkey tended to have lower life satisfaction than LB women in Belgium. Yet, we found the internalized heterosexism*nationality interaction to be nonsignificant for life satisfaction, (β = .055; SE = .030; 95% CI = −.005, .114). Similarly, the internalized heterosexism*sexual orientation interaction was not significant on life satisfaction (β = .025; SE = .027; 95% CI = −.028, .077). Thus, the results did not support our fourth hypothesis (Table 3).

Discussion

There is well-developed literature to support the negative association between internalized heterosexism and life satisfaction (Öztürk & Kındap, 2011; Michaels et al., 2019). Internalized heterosexism is reified through heteronormative cultural attitudes in families, education, health, religion, media, political and legal arrangements, and other political apparatuses. LGB individuals may internalize the heterosexist norms that exist in their social context, shaped by the countries in which they reside. The process of internalized heterosexism may function differently based on sexual orientation and for individuals who live in different countries with distinctive cultures. We investigated internalized heterosexism and life satisfaction within a sample of LB women residing in Turkey and Belgium, two countries that vary in regard to culture on the collectivistic-individualistic spectrum and in how their societies and institutions affirm and support LGBTQ rights. We also explored if nationality and sexual orientation would moderate the association between internalized heterosexism and life satisfaction.

In terms of results, we found LB women from Turkey experienced more internalized heterosexism than LB women from Belgium. This finding is not unexpected based on the social context for LGB individuals in each country, as LGB individuals are marginalized, stigmatized, and even imprisoned in Turkey when they refuse to conform to the heteronormative standards that promote heterosexual relationships as the norm. Although a same-sex relationship itself is not a crime in Turkey, there are various legal ways for discriminating against LGBTQ people; most importantly is the lack of legal arrangements aiming at preventing hate discourse and crimes against LGBTQ people (Engin, 2015; Göçmen & Yılmaz, 2017; Öztürk, 2011). Our finding that LB women in Belgium reported lower internalized heterosexism is consistent with minority stress theory and previous research that demonstrates LGB individuals experience less internalized heterosexism when living in societies with more robust policies against discrimination (Berg et al., 2013; Riggle et al., 2010), such as the anti-discrimination employment and housing laws in Belgium which include sexual orientation as a protected class. Also, per with minority stress theory, the social support that LGB people receive from LGB organizations may have a positive effect on the individuals’ decreased internalized heterosexism and psychological distress (Lorenzi et al., 2015; Riggle et al., 2010; Szymanski & Kashubeck-West, 2008). Another possible explanation of the differences between LB women’s internalized heterosexism based on nationality may be the accessibility and institutionalization of LGBTQ organizations in these countries, as LGBTQ organizations are more visible in Belgium. For example, annual pride parades have been held in Brussels since 1996 (Borghs, 2016), whereas Istanbul’s pride parade has been banned by the Turkish government since 2015 (Hajjaji, 2021).

Additionally, LB women in Belgium report higher life satisfaction as compared to LB women in Turkey, a finding similar to prior LGB life satisfaction studies that indicate more inclusive rights regarding sexual orientation and higher levels of social support towards LGB individuals increases life satisfaction (Berggen et al., 2018; Traeen et al., 2009; Wong & Tang, 2003). LGBTQ people in Turkey in both rural and urban areas face discrimination related to their sexual orientation in the areas of education, social, legal, work, and health care, which contributes to lower life satisfaction (Aslan, 2020). Our findings further support that the strong systematic social and structural inequality toward LGBTQ individuals in Turkey is harming their well-being, as the Turkish LB women reported lower life satisfaction.

Further, internalized heterosexism and life satisfaction may differ among LGB individuals depending on their specific sexual orientation. For example, bisexual individuals face discrimination both from the lesbian/gay community and the heterosexual community (Hayfield et al., 2014), leading to bi-erasure. Researchers have shown the additive effects of multiple types of oppression, including the negative impact of biphobia and bi-erasure on the mental health of bisexual individuals (Pennasilico & Amodeo, 2019; Ross et al., 2018). Therefore, we anticipated bisexual women would experience higher internalized heterosexism and lower life satisfaction as compared to lesbian women. Our findings, however, did not lend support to our hypothesis. A possible reason that there was no significant difference between the bisexual and lesbian woman in our study may be the shared gender (i.e., woman) between the two groups has more of a substantial impact on life satisfaction and internalized heterosexism than the effect of the differing sexual orientations. This finding indicates that it may be less important which sexual orientation sexual minority women identify with, but that the cumulative effect of discrimination related to being a woman who is a sexual minority has an equally strong impact on life satisfaction and internalized heterosexuality on LB women.

Turning to our hypotheses regarding moderation, we found that internalized heterosexism and nationality were both individually predictors of life satisfaction. The negative association between internalized heterosexism and life satisfaction paralleled the literature (Michaels et al., 2019; Newcomb & Mustanski, 2010). Our results, however, revealed no moderation of nationality and sexual orientation on the association between internalized heterosexism and life satisfaction, in contrast to what we predicted. At this point, we reaffirmed that LB women in Belgium have higher life satisfaction than LB women in Turkey. As we mentioned previously, an explanation of LB women in Belgium’s higher life satisfaction as compared to LB women in Turkey is that governmental and institutional support and LGBTQ human rights mechanisms are more inclusive in Belgium than in Turkey.

To sum up, our findings partly supported our hypotheses that nationality and internalized heterosexism both contributed in unique ways to the life satisfaction of LB women in Belgium as compared to LB women in Turkey. Specifically, LB women in Belgium indicated less internalized heterosexism and more satisfaction with life, consistent with minority stress theory (Meyer, 2003) and previous research that indicates increased anti-discrimination legislation (Berg et al., 2013; Riggle et al., 2010) and higher social support contribute to lower rates of internalized heterosexism (Lorenzi et al., 2015; Riggle et al., 2010; Szymanski & Kashubeck-West, 2008) and increased life satisfaction (Berggen et al., 2018; Traeen et al., 2009; Wong & Tang, 2003). The negative association between life satisfaction and internalized heterosexism also mirrored previous research findings (e.g., Michaels et al., 2019; Morandini et al., 2015; Wen & Zheng, 2019).

Limitations

Participants from both countries were predominantly economically disadvantaged, young, educated, and non-religious LB women. We collected data online with the help of announcements from LGBTQ, feminist, and queer organizations on their social media accounts, which means that the LB women who participated in the research were most likely involved in those organizations and/or LGBTQ activism. Therefore, our participants may not reflect the views of the larger LB female population, particularly for those who are less out or not associated with LGBTQ organizations and communities. For data collection, we used the same instrumentation in both countries; however, the estimates of validity were not separately established within each culture. Cross-cultural equivalence of the instruments was not the primary focus and thus assessed in the current study. Lastly, our study design was not longitudinal and experimental; therefore, causality cannot be inferred.

Implications for Future Research

Our findings have culture-specific and cross-cultural implications for further research studies. Research is warranted with different samples of LB women from more diverse backgrounds (e.g., economically advantaged, religiously affiliated) in Turkey and Belgium to confirm the findings of the current study. In addition, we encourage researchers to explore the constructs of internalized heterosexism, life satisfaction, and other determinants of LGBTQ health in studies that compare LGBTQ individuals who live in more inclusive countries to those that are more oppressive, to further examine how social context impacts minority stress. Variables representing cultural values, such as adherence to collectivistic and individualistic norms, should be assessed directly in comparison research. Future research studies also could involve queer women of varying sexual orientations, or include GB men, to further explore the intersectionality in identities within these groups. Although studies show that bisexual individuals are at greater risk of experiencing mental health and emotional well-being problems than lesbian women and gay men (Jorm et al., 2002; Stone et al., 2014; Tjepkema, 2008; Ward et al., 2014), we did not find any difference in the life satisfaction of the LB women in our study based on their sexual orientation. The association between different sexual orientations and determinants of health should be explored further, given these conflicting findings. Lastly, some researchers suggest that as the degree of sexual orientation disclosure increases, internalized heterosexism decreases (Herek et al., 1998; Szymanski & Chung, 2003), and consequently, life satisfaction increases (Öztürk & Kındap, 2011; Michaels et al., 2019). Hence, we suggest researchers include the level of outness in future studies to examine the moderating role of coming out on the relationship between internalized heterosexism and life satisfaction.

Practical Implications

Mental health professionals need to attune to and address the negative consequences of internalized heterosexism, which may contribute to mental health challenges, such as anxiety and depression, among LGBTQ patients. The findings of our study demonstrate the impact of social context, as indicated by nationality, on internalized heterosexism and life satisfaction in LB women. Mental health professionals working with LB women should consider how internalized heterosexism impacts their life satisfaction and well-being, and how devaluation of self and/or LB identities is shaped by cultural socialization in patients’ country of origin and current residence. Further, mental health professionals should utilize LGBTQ-affirmative, social justice-based, and constructivist-oriented therapies that locate the problem in the societal context and not the individual, which embolden self- and social advocacy to enact change at a societal and institutional level. Mental health professionals also need account for the social context of the country in which their patients reside in encourage appropriate and effective advocacy; for example, attending a pride parade in Turkey may lead to legal charges and jail time for LGBTQ individuals (Hajjaji, 2021). We are not suggesting that LGBTQ individuals in Turkey should not take to the streets to advocate for their rights; however, mental health professionals should help their patients explore the consequences of their decisions, including when they come out to others and how they choose to champion LGBTQ rights in their countries. That said, our findings support the tenants of minority stress theory and previous research that indicate societies that are more inclusive and affirmative towards LGBTQ individuals reduce stress cycle factors such as internalized heterosexism and improve LGBTQ individuals’ well-being. Thus, mental health professionals have a responsibility as social advocates and agents of change in improving the health outcomes and well-being of LGBTQ individuals across the world. We need to be vocal, both as individual professionals and as a profession, when we see heteronormative practices that harm LGBTQ individuals to generate sustained social, institutional and legal change and affirmative environments where LGBTQ individuals can flourish.

Conclusion

This study is one of the few that compares sexual minority populations living in two countries with unique cultures and varying climates towards LGBTQ individuals, enabling us to explore the impact of the social context, as defined by nationality, on participants’ experiences of stress cycle factors and their life satisfaction. Further, this study is also unique in the number of bisexual participants, enabling us to compare the experiences of bisexual and lesbian women. Our results indicate that a) internalized heterosexism correlates to the life satisfaction of LB women, and b) social context seems to contribute to the internalized heterosexism and life satisfaction for LB women, as these constructs varied by nationality. Thus, our findings indicate social context may influence health outcomes for LB women; thus, researchers should continue to explore how multiple oppressions interact and add to stress for minority groups. Lastly, our findings demonstrate the continued need for advocacy on the part of mental health professionals to change the social and cultural contexts to be more affirmative and inclusive of LGBTQ identities, which will contribute to improvement in their overall well-being and health.

Notes

As of February 2021, 2000 Turkish liras equals to $271.14 United States Dollars and 2000 Euros equals to $2445.00 United States Dollars.

References

Aslan, K. (2020). Turkiye’de lgbt olmak: Ayrimcılık şiddet, memnuniyet üçgeninde kesit veri analizi (Being lgbt in Turkey: Sectional data analysis in the triangle of discrimination, violence and satisfaction). [unpublished master’s thesis]. Akdeniz Universitesi (Akdeniz University), Antalya, Turkey.

Balsam, K. F., & Szymanski, D. M. (2005). Relationship quality and domestic violence in women’s same-sex relationships: The role of minority stress. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 29, 258–269. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2005.00220.x.

Barnes, D. M., & Meyer, I. H. (2012). Religious affiliation, internalized homophobia, and mental health in lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 82(4), 505–515. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2012.01185.x.

Barnett, A. P., del Rio-Gonzalez, A. M., Parchem, B. P., Aguayo-Romero, R., Nakamura, N., Calabrese, S. K., Poppen, P. J., & Zea, M. C. (2019). Content analysis of psychological research with lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people of color in the United States: 1969–2018. American Psychologist, 74(8), 898–911. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000562.

Berg, R. C., Ross, M. W., Weatherburn, P., & Schmidt, A. J. (2013). Structural and environmental factors are associated with internalized homonegativity in men who have sex with men: Findings from the European msm internet survey (emis) in 38 countries. Social Science and Medicine, 78, 61–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.033.

Berg, R. C., Munthe-Kaas, H. M., & Ross, M. W. (2016). Internalized homonegativity: A systematic mapping review of empirical research. Journal of Homosexuality, 63(4), 541–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2015.1083788.

Berggen, N., Bjornskov, C., & Nilsson, T. (2018). Do equal rights for a minority affect general life satisfaction? Journal of Happiness Studies, 19, 1465–1483. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9886-6.

Borghs, P. (2016). The gay and lesbian movement in Belgium from the 1950s to the present. QED: A Journal in GLBTQ Worldmaking, 3(3), 29–70. doi:https://doi.org/10.14321/qed.3.3.0029

Central Intelligence Agency (2021). The World Factbook, 2021: Field Listing – Religions. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/field/religions/.

Chow, P. K. Y., & Cheg, S. T. (2010). Shame, internalized heterosexism, lesbian identity, and coming out to others: A comparative study of lesbians in mainland China and Hong Kong. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57, 92–104. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017930.

Dewaele, A., Vincke, J., Cox, N., & Dhaenens, F. (2009). Het discours van jongeren over man-vrouwrolpatronen en holebiseksualiteit. Over flexen, players en metroseksuelen. [the discourse of youngsters on man-woman role patterns and homosexuality. About flexibles, players and metrosexuals.]. Steunpunt Gelijkekansenbeleid.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13.

Engin, C. (2015). LGBT in Turkey: Policies and experiences. Social Sciences, 4, 838–858. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci4030838

Equaldex. (2019). Compare LGBT rights in Belgium and Turkey. Retrieved fromhttps://www.equaldex.com/compare/belgium/turkey.

Fragoso, J. M., & Kashubeck, S. (2000). Machismo, gender role conflict, and mental health in Mexican American men. Psychology of Men and Masculinity, 1, 87–97. https://doi.org/10.1037/1524-9220.1.2.87.

Göçmen, İ., & Yılmaz, V. (2017). Exploring perceived discrimination among LGBT individuals in Turkey in education, employment, and health care: Results of an online survey. Journal of Homosexuality, 64(8), 1052–1068. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2016.1236598.

Hair Jr., J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (2013). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Prentice-Hall.

Hajjaji, D. (2021). LGBTQ art arrests inflame Turkey student protests. Newsweek. https://www.newsweek.com/lgbtq-art-arrests-inflame-turkey-student-protests-1565832

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Hayfield, N., Clarke, V., & Halliwell, E. (2014). Bisexual women’s understandings of social marginalisation: ‘The heterosexuals don’t understand us but nor do the lesbians. Feminism & Psychology, 24(3), 352–372. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353514539651.

Herek, G. M., Cogan, J. C., Gillis, J. R., & Glunt, E. K. (1998). Correlates of internalized homophobia in a community sample of lesbians and gay men. Journal of the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association, 2, 17–26.

Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede Model in context. Online Readings in Psychology & Culture, 2(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1014- ILGA-Europe (2020). Annual review of the human rights situation of lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, and intersex people in Europe. Brussels, Belgium: ILGA-Europe. Retrieved from https://www.ilga-europe.org/annualreview/2020

Jorm, A. F., Korten, A. E., Rodgers, B., Jacomb, P. A., & Christensen, H. (2002). Sexual orientation and mental health: Results from a community survey of young and middle-aged adults. British Journal of Psychiatry, 180(5), 423–427.

Khan, M., Ilcisin, M., & Saxton, K. (2017). Multifactorial discrimination as a fundamental cause of mental health inequities. International Journal for Equity in Health, 16(1), 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-017-0532-z.

Lange, T. (2010). Culture and life satisfaction in developed and less developed nations. Applied Economics Letters, 17, 901–906. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504850802552309.

Liu, W. M., & Iwamoto, D. K. (2006). Asian American men ' s gender role conflict: The role of Asian values, self-esteem, and psychological distress. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 7(3), 153–164. https://doi.org/10.1037/1524-9220.7.3.153.

Lorenzi, G., Miscioscia, M., Ronconi, L., Pasquali, C. E., & Simonelli, A. (2015). Internalized stigma and psychological well-being in gay men and lesbians in Italy and Belgium. Social Sciences, 4, 1229–1242. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci4041229.

McCarn, S. R., & Fassinger, R. E. (1996). Revisioning sexual minority identity formation: A new model of lesbian identity and its implications. The Counseling Psychologist, 24(3), 508–534. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000096243011.

McCormick-Huhn, K., Warner, L. R., Settles, I. H., & Shields, S. A. (2019). What if psychology took intersectionality seriously? Changing how psychologists think about participants. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 43(4), 445–456. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684319866430.

McLaren, S. (2016). The interrelations between internalized homophobia, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among Australian gay men, lesbians, and bisexual women. Journal of Homosexuality, 63(2), 156–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2015.1083779.

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674.

Michaels, C., Choi, N. Y., Adams, E. M., & Hitter, T. L. (2019). Testing a new model of sexual minority stress to assess the roles of meaning in life and internalized heterosexism on stress-related growth and life satisfaction. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 6(2), 204–216. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000320.

Mink, M., Lindley, L. L., & Weinstein, A. A. (2014). Stress, stigma, and sexual minority status: The intersectional ecology model of LGBTQ health. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services, 26(14), 502–521. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538720.2014.953660.

Morandini, J. S., Blaszczynski, A., Ross, M. W., Costa, D. S., & Dar-Nimrod, I. (2015). Essentialist beliefs, sexual identity uncertainty, internalized homonegativity, and psychological wellbeing in gay men. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62, 413–424. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000072.

Newcomb, M. E., & Mustanski, B. (2010). Internalized homophobia and internalizing mental health problems: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(8), 1019–1029. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.07.003.

Norwalk, K. E., Vandiver, B. J., White, A. M., & Englar-Carlson, M. (2011). Factor structure of the gender role conflict scale in African American and European American men. Psychology of Men and Masculinity, 12(2), 128–143. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022799.

Oyserman, D., Coon, H. M., & Kemmelmeier, M. (2002). Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 128(1), 3–72. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.128.1.3.

Özbay, C., & Soydan, S. (2003). Eşcinsel kadınlar: Yirmi dört tanıklık [Lesbians: Twenty four testimonies]. Metis Yayınları.

Öztürk, M. B. (2011). Sexual orientation discrimination: Exploring the experiences of lesbian, gay, and bisexual employees in Turkey. Human Relations, 68(8), 1099–1118. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726710396249.

Öztürk, P., & Kındap, Y. (2011). Lezbiyenlerde içselleştirilmiş homofobi ölçeğinin psikometrik özelliklerinin incelenmesi [Turkish adaptation of the lesbian internalized homophobia scale: A study of validity and reliability]. Türk Psikoloji Yazıları [Turkish Psychology Articles], 14(28), 24–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726710396249.

Pennasilico, A. & Amodeo, A. L. (2019). The invisi_les: Biphobia, bisexual, erasure, and their impact on mental health. PuntOorg International Journal, 4(1), 21-28. Doi: https://doi.org/10.19245/25.05.pij.4.1.4.

Poushter, J., & Kent, N. O. (2020). The global divide on homosexuality persists. Pew research center. Retrieved may 6, 2021 from https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2020/06/25/ global-divide-on-homosexuality-persists/pg_2020-06-25_global-views- homosexuality_0-01/.

Rich, A. (1980). Compulsory heterosexuality and lesbian existence. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 5, 631–660. https://doi.org/10.1086/493756.

Riggle, E. D. B., Rostosky, S. S., & Horne, S. (2010). Does it matter where you live? Nondiscrimination laws and the experiences of LGB residents. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 7, 168–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-010-0016-z.

Ross, L. E., Salway, T., Tarasoff, L. A., MacKay, J. M., Hawkins, B. W., & Fehr, C. P. (2018). Prevalence of depression and anxiety among bisexual people compared to gay, lesbian, and heterosexual individuals: A systemic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Sex Research, 55(4–5), 435–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1387755.

Şah, U. (2011). Türkiye’deki gençlerin cinsel yönelimlere ilişkin sosyal temsilleri ve homofobi [the social representations of youth in Turkey about sexual orientations]. Türk Psikoloji Yazıları [Turkish Psychology Articles], 14(27), 88–99.

Stone, D. M., Luo, F., Ouyang, L., Lippy, C., Hertz, M. F., & Crosby, A. E. (2014). Sexual orientation and suicide ideation, plans, attempts, and medically serious attempts: Evidence from local youth risk behavior surveys, 2001–2009. American Journal of Public Health, 104, 262–271.

Szymanski, D. M. (2005). Heterosexism and sexism as correlates of psychological distress in lesbians. Journal of Counseling and Development, 83, 355–360. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2005.tb00355.x.

Szymanski, D. M., & Chung, Y. B. (2001). The lesbian internalized homophobia scale: A rational/theoretical approach. Journal of Homosexuality, 41(2), 37–52. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v41n02_03.

Szymanski, D. M., & Chung, Y. B. (2003). Feminist attitudes and coping resources as correlates of lesbian internalized heterosexism. Feminism & Psychology, 13, 369–389. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353503013003008.

Szymanski, D. M., & Hendrichs-Beck, C. (2013). Exploring sexual minority women’s experiences of external and internalized heterosexism and sexism and their links to coping and distress. Sex Roles, 70, 28–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-013-0329-5.

Szymanski, D. M., & Kashubeck-West, S. (2008). Mediators of the relationship between internalized oppressions and lesbian and bisexual women’s psychological distress. The Counseling Psychologist, 36(4), 575–594.. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000007309490.

Szymanski, D. M., & Owens, G. P. (2008). Do coping styles moderate or mediate the relationship between internalized heterosexism and sexual minority women’s psychological distress? Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32, 95–104.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00410.x.

Szymanski, D. M., & Sung, M. R. (2013). Asian cultural values, internalized heterosexism, and sexual orientation disclosure among Asian American sexual minority persons. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 7, 257–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538605.2013.812930.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Allyn and Bacon.

Traeen, B., Martinussen, M., Vitters, J., & Saini, S. (2009). Sexual orientation and quality of life among students from Cuba, Norway, India, and South Africa. Journal of Homosexuality, 56(5), 655–669. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918360903005311.

Tjepkema, M. (2008). Health care use among gay, lesbian, and bisexual Canadians. Health Reports, 19(1), 53–64.

Ward, B. W., Dahlhamer, J. M., Galinsky, A. M., & Joestl, S. S. (2014). Sexual orientation and health among U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2013. National Health Statistics and Reports, 77. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr077.pdf

Wen, G., & Zheng, L. (2019). The influence of internalized homophobia on health-related quality of life and life satisfaction among gay and bisexual men in China. American Journal of Men’s Health, 13(4), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988319864775.

Wong, C., & Tang, C. S. (2003). Personality, psychosocial variables, and life satisfaction of Chinese gay men in Hong Kong. Journal of Happiness Studies, 4(3), 285–293. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026211323099.

World Health Organization (2016). Gender, equity, and human rights. Retrieved May 6, 2021 from https://www.who.int/gender-equity-rights/news/20170329-health-and-sexual-diversity-faq.pdf?ua=1

Acknowledgments

The work presented here was largely performed while the first author was a post-doctoral researcher at Université Libre de Bruxellesé [and is now at Oslo University].

The second author is thankful for the financial support provided by the Fulbright Postdoctoral Research Grant from the Turkish Fulbright Commission, while part of this paper was written. The second author is also grateful to Dr. Frank D. Fincham for his support and to the Family and Child Sciences at Florida State University for the hospitality during the post-doc.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Oslo (incl Oslo University Hospital).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest/Competing Interests

We have no conflicts of interest that might affect the study.

Availability of Data and Material

The data associated with the paper is available and can be accessed upon request by the editors/reviewers.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Ethics Approval

The project was conducted under all relevant ethical standards and all requirements of the Université Libre de Bruxelles, Belgium.

Consent to Participate

Participants were agreed to participate after they signed an informed consent separately from the main documents.

Consent for Publication

Participants gave consent for the publication of their data.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ummak, E., Toplu-Demirtaş, E., Pope, A.L. et al. The influence of internalized heterosexism on life satisfaction: comparing sexual minority women in Belgium and Turkey. Curr Psychol 42, 7421–7432 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02068-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02068-w