Abstract

Suicide belongs to the leading causes of death worldwide. The present longitudinal study investigated physical activity (for example jogging, cycling) and positive mental health (PMH) as potential factors that can reduce the risk of suicide ideation and suicidal behavior. Data of 223 participants (79.4% women; Mage (SDage) = 22.85 (4.05)) were assessed at two measurement time points over a three-year period (2016: first measurement = baseline (BL); 2019: second measurement = follow-up (FU)) via online surveys. The results reveal a significant positive relationship between higher physical activity (BL) and higher PMH (BL). Higher scores of both variables were significantly negatively linked to lower suicide-related outcomes (FU). Moreover, the association between higher physical activity (BL) and lower suicide-related outcomes (FU) was significantly mediated by higher PMH (BL). The current findings demonstrate that physical activity in combination with PMH can reduce the risk of suicide-related outcomes. Fostering physical activity and PMH may be relevant strategies in the prevention of suicide ideation and suicide behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Worldwide, suicide is among the major causes of deaths. Every year, about 800,000 people die to suicide (World Health Organization 2014). In Germany, a total of 9,396 suicide deaths were registered in the year 2018; on average 25 people died every day to suicide (German Federal Statistical Office 2020). Especially, young individuals who belong to the age group that is termed as emerging adulthood (18 to 29 years; Arnett 2000) are at enhanced risk for suicide ideation and suicidal behavior in Germany as well as in other countries (e.g., De Catanzaro 1991, 1995; Nock et al. 2014; Voss et al. 2019; World Health Organization 2014).

Suicide ideation – including the passive wish to die as well as concrete considerations how to die by suicide – is an important predictor of suicide attempts, i.e., self-injurious actions intended to kill oneself (O’Connor and Nock 2014). Jahangard et al. (2020, p.76) described suicide ideation as “the result of biased social cognition, social impairment and disconnected social life”. Individuals at risk for suicide typically perceive themselves as a burden for their social network and believe that their death will be a benefit for others (Joiner 2005; Joiner et al. 2016). Suicide-related outcomes (i.e., suicide ideation and suicide attempts) are closely linked to depression (De Catanzaro 1991, 1995): On the one hand, suicide ideation and suicide attempts are key criteria of major depressive disorders (see Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association 2013). On the other hand, depression symptoms positively predict suicide-related outcomes (Ribeiro et al. 2018; Teismann et al. 2018). Furthermore, both suicide ideation and suicide attempts are positively linked to sleep disturbances (Khazaie et al. 2020; Krakow et al. 2011; Pompili et al. 2013; Stanley et al. 2017), anxiety symptoms (Ribeiro et al. 2014), and can also be associated with a state of physical and psychological overarousal (Ribeiro et al. 2014; Rudd et al. 2006). On the neurobiological basis, individuals with enhanced suicide ideation and these who survived a suicide attempt have decreased levels of (unextracted) oxytocin concentration (Chu et al. 2020; Jahangard et al. 2020). The decrease of the hormone is positively associated with stress experience, feelings of social exclusion, disconnection and sadness (Bosch and Young 2018; Pohl et al. 2019).

Especially against the background that recent research described an increase of both suicide ideation and suicide attempts in the last years especially among young people (Twenge et al. 2018), it is of great importance to reveal factors that can directly or in interaction with each other reduce the risk of suicide-related outcomes, specifically in emerging adulthood.

Previous research reported that physical activity offers profound mental health benefits: As such, research suggests that physical activity programs are as effective as other intervention strategies in the treatment of unipolar depressive disorders (Kvam et al. 2016; Schuch et al. 2016), as well as the treatment of schizophrenia (Firth et al. 2015). A recent meta-analysis found evidence that physical activity confers a significant protective effect on suicide ideation in adults (Vancampfort et al. 2018) and some studies described that physical active persons demonstrated lower rates of suicide attempts (Simon et al. 2004; Taliaferro et al. 2011). However, other research reported no significant associations between physical activity and suicide ideation (Choquet et al. 1993) as well as suicide attempts (Sabo et al. 2005). Considering the mixed findings, Lester et al. (2010) assumed that the link between physical activity and suicide-related outcomes could be mediated through further factors such as the level of mental health. The authors emphasized the need of longitudinal research to understand the mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of physical activity.

According to the dual-factor model (e.g., Keyes 2005), mental health consists of two interrelated but separate unipolar dimensions: negative and positive. Previous research on suicide-related outcomes mainly focused on the negative dimension: Physical activity can reduce factors such as the experience of stress, depression symptoms and anxiety symptoms; factors known to foster suicide-related outcomes (Brailovskaia et al. 2018; Oler et al. 1994; Schuch et al. 2016; Stubbs et al. 2017; Wunsch et al. 2017). Moreover, one might speculate that engagement in team-based physical activity such as football and basketball might decrease feelings of disconnection and social exclusion that both are associated with the oxytocin level (Babiss and Gangwisch 2009). Thus, it can be assumed that variables of negative mental health (e.g., depression and anxiety symptoms) mediate the link between physical activity and suicide-related outcomes. If physical activity reduces the negative variables, this can contribute to the decrease of suicide-related outcomes.

However, it remains unclear, whether the positive dimension of mental health is also significantly included in the association between physical activity and suicide-related outcomes. Positive mental health (PMH) – as assessed with the PMH-Scale (Lukat et al. 2016) – comprises facets of subjective well-being such as life satisfaction and psychological well-being, especially self-acceptance and self-efficacy (Teismann and Brailovskaia 2020). Following previous research, PMH can serve as a protective factor against suicide-related outcomes (e.g., Brailovskaia et al. 2019). In cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (Brailovskaia et al. 2019; Siegmann et al. 2019; Teismann et al. 2018), PMH contributed to a lower risk of suicide-related outcomes and predicted remission from suicidal thoughts and reduced suicide attempts (Teismann et al. 2019; Teismann et al. 2016). On this background, it can be assumed that PMH may – as a mediator – fostering the impact of physical activity on suicide-related outcomes (cf., Johnson 2016): The engagement in physical activity could foster the experience of positive emotions. Particularly, the improvement of one’s physical performance and the achievement of self-imposed physical goals, for instance, the increasing of the own jogging speed, might contribute to mood improvement and increase an individual’s sense of control and self-efficacy (Eime et al. 2013; Rebar et al. 2015). These factors could contribute to an increase of PMH. An enhanced level of PMH could therefore contribute to the decrease of suicide-related outcomes. Thus, the combined effect of physical activity and PMH might be an effective way to reduce suicide ideation and suicide attempts. Following the advice of Lester et al. (2010) who emphasized the need for longitudinal research, the present study investigated this assumption using a longitudinal design – two measurement time points (baseline, BL, and follow-up, FU) with a three-year time interval in a sample of individuals who mainly belonged to the emerging adulthood in Germany. A confirmation of this assumption might reveal important knowledge for programs that focus on the reduction of suicide-related outcomes and the suicide rate.

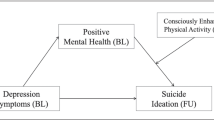

We expected that suicide-related outcomes (FU) are negatively linked to physical activity (BL) (Hypothesis 1a) and PMH (BL) (Hypothesis 1b). We assumed that physical activity (BL) is positively related to PMH (BL) (Hypothesis 1c). Moreover, we expected that PMH (BL) negatively mediates the association between physical activity (BL) and suicide-related outcomes (FU) (Hypothesis 2).

Method

Participants

In October 2016, 250 randomly collected students of a large German university in the Ruhr region received an e-mail invitation to the first online survey (BL). In October 2019, the 237 persons who had completed the first survey, were invited by e-mail to complete the second online survey (FU). Participation was voluntary and compensated by course credits. In total, 223 persons (79.4%, n = 177 women; BL: Mage (SDage) = 22.85 (4.05); range: 18–40) completed both surveys. At BL, all participants were students. At FU, 30.5% (n = 68) had finished their studies and were working. The responsible Ethics Committees approved the conduction of the present study. Participants were properly instructed and gave online their informed consent to participate. The privacy rights of human subjects were fully observed.

Measures

Physical Activity

The item “How frequently do you engage in physical exercise (e.g., swimming, cycling, jogging)?” that is rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never, 5 = four times a week or more) assessed frequency of physical activity. This item was previously reported to be a reliable and valid instrument to measure physical activity with a satisfying mean test-retest reliability ranging between rmtrr = .60 and .82 (Brailovskaia et al. 2020; Milton et al. 2011).

Positive Mental Health Scale (PMH-Scale; Lukat et al. 2016)

The unidimensional PMH-Scale measures subjective and psychological aspects of well-being. The nine items (e.g., “I enjoy my life”, “I feel that I am actually well equipped to deal with life and its difficulties”) are rated on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = do not agree, 3 = agree). Current internal reliability of the scale was: Cronbach’s αBL = .93.

Suicide-Related Outcomes

Item 1 (“Have you ever thought about or attempted to kill yourself?”) of the Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R; Osman et al. 2001) that is rated on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = never, 6 = I have attempted to kill myself, and really hoped to die) was included to assess lifetime suicide-related outcomes. This item was recommended for screening purpose and has repeatedly been used in clinical and non-clinical samples. A cutoff score of 2 in the SBQ-R Item 1 has been shown to be most useful in differentiating between suicidal and non-suicidal individuals (Osman et al. 2001).

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS 24 and the macro Process version 2.16.1 (www.processmacro.org/index.html; Hayes 2013). After descriptive statistics and zero-order bivariate correlations, a mediation model (Process: model 4) was calculated with the basic relationship between physical activity (BL, predictor) and lifetime suicide-related outcomes (FU, outcome) (path c, total effect). The path of physical activity (BL) to PMH (BL, mediator) was denoted by a; the path of PMH (BL) to suicide-related outcomes (FU) was denoted by b. The indirect effect was represented by the combined effect of path a and path b. Path c’ denoted the direct effect of physical activity (BL) to suicide-related outcomes (FU) after the inclusion of PMH (BL) in the model. Age and gender (both BL, covariates) were included as control variables. The bootstrapping procedure (10.000 samples) that provides accelerated confidence intervals (95% CI) assessed the mediation effect. PM (the ration of indirect effect to total effect) served as mediation effect measure. A priori conducted power analyses (G*Power program, version 3.1) revealed that the current sample size was sufficient for valid results (power > .80, α = .05, effect size f2 = 0.15; Mayr et al. 2007).

Results

Of the 223 participants, 56% (n = 125) reported lifetime suicide ideation/behavior (SBQ-R > 0), 2.7% (n = 6) reported lifetime suicide attempts. Suicide-related outcomes (FU; M (SD) = 1.92 (1.10), range: 1–6) were significantly negatively correlated with physical activity (BL; M (SD) = 3.11 (1.18), range: 1–5), r = −.260, p < .001, and with PMH (BL; M (SD) = 18.40 (6.12), range: 0–27), r = −.469, p < .001. Physical activity (BL) was significantly positively correlated with PMH (BL), r = .394, p < .001.

Figure 1 shows the results of the bootstrapped mediation analysis. The basic relationship between physical activity (BL) and suicide-related outcomes (FU) was significant (total effect, c: p < .001). After the inclusion of PMH (BL) in the model, this relationship was no longer significant (direct effect, c’: p = .215). The link between physical activity (BL) and PMH (BL) (a: p < .001), and the association between PMH (BL) and suicide-related outcomes (FU) (b: p < .001) were both significant. The indirect effect (ab) was significant, b = −.144, SE = .040, 95% CI [−.237, −.079]; PM: b = .659, SE = .565, 95% CI [.375, 1.299].

Mediation model including physical activity (BL, predictor), positive mental health (BL, mediator), and suicide-related outcomes (FU, outcome)

Note. c = total effect, c’ = direct effect; b = standardized regression coefficient, SE = standard error, CI = confidence interval, BL = baseline, FU = follow-up.

Discussion

For individuals who belong to the emerging adulthood, suicide is the second leading cause of death worldwide (World Health Organization 2014); suicide rates increased remarkably in the last years especially for this age group (Twenge et al. 2018). Therefore, effective programs that contribute to the prevention of suicide ideation and suicide attempts are of great importance. The development of such programs depends on the available knowledge about the factors that can directly or in interaction with each other reduce the risk of suicide-related outcomes.

While some earlier studies described that engagement in physical activity can contribute to the reduction of suicide-related outcomes (e.g., Taliaferro et al. 2011; Vancampfort et al. 2018), other research did not confirm this finding (e.g., Choquet et al. 1993; Sabo et al. 2005). Therefore, Lester et al. (2010) emphasized the importance of the identification of potential mediators of the relationship between physical activity and suicide-related outcomes. Considering previous research (e.g., Schuch et al. 2016; Stubbs et al. 2017), it can be assumed that factors that belong to the negative dimension of mental health such as depression and anxiety symptoms may serve as mediators in this relationship. However, the role of the positive dimension of mental health remained so far unclear. The present longitudinal findings from an emerging adulthood sample contribute to the clarification of this issue. They reveal that PMH can reinforce the protective effect of physical activity.

As expected, physical activity and PMH were negatively related to suicide-related outcomes three years later (confirmation of Hypothesis 1a and Hypothesis 1b). Both were positively associated (confirmation of Hypothesis 1c). Moreover, PMH mediated the association between physical activity and suicide-related outcomes (confirmation of Hypothesis 2). The present findings complement previous studies showing that physical activity protects against suicide ideation and suicidal behavior (Vancampfort et al. 2018). Also, they replicate previous findings that PMH exerts a protective effect on suicide-related outcomes (e.g., Teismann et al. 2016). Moreover, they reveal that the combination of physical activity and PMH can reduce the risk of suicide-related outcomes over a three-year follow-up interval. Thus, based on current results, it can be assumed that the protective influence of physical activity against suicide-related outcomes is due to heightened PMH: If physical activity translates into PMH, i.e., life satisfaction, self-acceptance and self-efficacy, then suicide ideation and suicide attempts become less likely. This result-pattern might explain why physical activity is not always associated with suicide-related outcomes (e.g., Choquet et al. 1993); it depends on its influence on (positive) self-appraisals. This finding confirms and complements the assumption of Lester et al. (2010) considering the mediating role of mental health. Thus, the negative dimension and the positive dimension of mental health (Keyes 2005) are both involved in the association between physical activity and suicide-related outcomes.

The present study includes several strengths and limitations. A significant strength involves the three-year prospective design which offers advantages over previous cross-sectional research addressing physical activity and suicide-related outcomes. Moreover, the present study focuses on the combination of physical activity and PMH, while previous research mostly investigated negative mental health factors. However, several study limitations warrant recognition. First, the study does not include a rigorous physical activity assessment. Thus, it is neither possible to investigate whether different kinds of physical activity show a differential association with suicide-related outcomes, nor is it possible to differentiate between the effect of physical activity compared to the effect of sport participation – with the latter offering not only physical activity but also integration into social networks (cf., Taliaferro et al. 2011). Second, the single-item measure of suicide ideation/behavior might have lacked specificity. Multi-item measures would produce greater precision of measurement and possibly affect results. Third, the predominately female sample limits the generalizability of the current results. Fourth, researchers and practitioners should not overstate associations between physical activity and suicide-related outcomes, since the here-found effects are of a rather modest size.

Clinically, the findings of the current study suggest that it may be important to account both for the presence of physical activity and PMH in addition to risk factors, when assessing individuals at risk for suicide. Furthermore, it could be useful to incorporate participation in physical activity in suicide prevention programs. The engagement in physical activity can contribute to the experience of positive emotions and to the increase of the sense of control that individuals with enhanced suicide risk often miss. This can foster the PMH level which may reduce the suicide-related outcomes. Moreover, the enhancement of the individual PMH level by other interventions that enable positive experiences and the increase of self-efficacy can strengthen the protective combined effect of physical activity and PMH on suicide ideation and suicide attempts.

In summary, the present results indicate a protective association between physical activity and suicide-related outcomes over a three-year period and underscore the importance of PMH as a protective factor against suicide ideation and suicide attempts.

Change history

16 October 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02330-1

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480.

Babiss, L. A., & Gangwisch, J. E. (2009). Sports participation as a protective factor against depression and suicidal ideation in adolescents as mediated by self-esteem and social support. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 30, 376–384.

Bosch, O. J., & Young, L. J. (2018). Oxytocin and social relationships: From attachment to bond disruption. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences, 35, 97–117.

Brailovskaia, J., Teismann, T., & Margraf, J. (2018). Physical activity mediates the association between daily stress and Facebook addiction disorder (FAD) – A longitudinal approach among German students. Computers in Human Behavior, 86, 199–204.

Brailovskaia, J., Forkmann, T., Glaesmer, H., Paashaus, L., Rath, D., Schönfelder, A., Juckel, G., & Teismann, T. (2019). Positive mental health moderates the association between suicide ideation and suicide attempts. Journal of Affective Disorders, 245, 246–249.

Brailovskaia, J., Ströse, F., Schillack, H., & Margraf, J. (2020). Less Facebook use–more well-being and a healthier lifestyle? An experimental intervention study. Computers in Human Behavior, 108, 106332.

Choquet, M., Kovess, V., & Poutignat, N. (1993). Suicidal thoughts among adolescents: An intercultural approach. Adolescence, 28(111), 649–659.

Chu, C., Hammock, E. A. D., & Joiner, T. E. (2020). Unextracted plasma oxytocin levels decrease following in-laboratory social exclusion in young adults with a suicide attempt history. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 121, 173–181.

De Catanzaro, D. (1991). Evolutionary limits to self-preservation. Ethology and Sociobiology, 12(1), 13–28.

De Catanzaro, D. (1995). Reproductive status, family interactions, and suicidal ideation: Surveys of the general public and high-risk groups. Ethology and Sociobiology, 16(5), 385–394.

Eime, R. M., Young, J. A., Harvey, J. T., Charity, M. J., & Payne, W. R. (2013). A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for adults: Informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 10(1), 135–148.

Firth, J., Cotter, J., Elliott, R., French, P., & Yung, A. R. (2015). A systematic review and meta-analysis of exercise interventions in schizophrenia patients. Psychological Medicine, 45, 1343–1361.

German Federal Statistical Office. (2020). Todesursachen: Suizide. Retrieved from https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Gesundheit/Todesursachen/Tabellen/suizide.html

Hayes, A. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. London: Guilford Press.

Jahangard, L., Shayganfard, M., Ghiasi, F., Salehi, I., Haghighi, M., Ahmadpanah, M., Bahmani, D. S., & Brand, S. (2020). Serum oxytocin concentrations in current and recent suicide survivors are lower than in healthy controls. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 128, 75–82.

Johnson, J. (2016). Resilience: The bi-dimensional framework. In A. M. Wood & J. Johnson (Eds.), Positive clinical psychology (pp. 73–88). Chichester: Wiley & Sons.

Joiner, T. E. (2005). Why people die by suicide. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Joiner, T. E., Hom, M. A., Hagan, C. R., & Silva, C. (2016). Suicide as a derangement of the self-sacrificial aspect of eusociality. Psychological Review, 123(3), 235–254.

Keyes, C. L. (2005). Mental illness and/or mental health? Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(3), 539–548.

Khazaie, H., Zakiei, A., McCall, W. V., Noori, K., Rostampour, M., Sadeghi Bahmani, D., & Brand, S. (2020). Relationship between sleep problems and self-injury: A systematic review. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 1–16.

Krakow, B., Ribeiro, J. D., Ulibarri, V. A., Krakow, J., & Joiner, T. E. (2011). Sleep disturbances and suicidal ideation in sleep medical center patients. Journal of Affective Disorders, 131(1–3), 422–427.

Kvam, S., Kleppe, C. L., Nordhus, I. H., & Hovland, A. (2016). Exercise as a treatment for depression: A meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 202, 67–86.

Lester, D., Battuelo, M., Innamorati, M., Falcone, I., DeSimoni, E., Del Bono, S. D., Tatarelli, R., & Pompili, M. (2010). Participation in sport activities and suicide prevention. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 41, 58–72.

Lukat, J., Margraf, J., Lutz, R., van der Veld, W. M., & Becker, E. S. (2016). Psychometric properties of the positive mental health scale (PMH-scale). BMC Psychology, 4, 1–14.

Mayr, S., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Faul, F. (2007). A short tutorial of GPower. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 3, 51–59.

Milton, K., Bull, F. C., & Bauman, A. (2011). Reliability and validity testing of a single-item physical activity measure. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 45(3), 203–208.

Nock, M. K., Borges, G., & Ono, Y. (2014). Suicide. Global perspec-tives from the WHO world mental health survey. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

O’Connor, R. C., & Nock, M. K. (2014). The psychology of suicidal behaviour. Lancet Psychiatry, 1(1), 73–85.

Oler, M. J., Mainous, A. G., Martin, C. A., Richardson, E., Haney, A., Wilson, D., & Adams, T. (1994). Depression, suicidal ideation, and substance use among adolescents. Are athletes at less risk? Archives of Family Medicine, 3(9), 781–785.

Osman, A., Bagge, C. L., Gutierrez, P. M., Konick, L. C., Kopper, B. A., & Barrios, F. X. (2001). The suicidal behaviors questionnaire-revised (SBQ-R). Assessment, 8, 443–454.

Pohl, T. T., Young, L. J., & Bosch, O. J. (2019). Lost connections: Oxytocin and the neural, physiological, and behavioral consequences of disrupted relationships. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 136, 54–63.

Pompili, M., Innamorati, M., Forte, A., Longo, L., Mazzetta, C., Erbuto, D., Ricci, F., Palermo, M., Stefani, H., Seretti, M. E., Lamis, D. A., Perna, G., Serafini, G., Amore, M., & Girardi, P. (2013). Insomnia as a insomnia as a predictor of high-lethality suicide attempts. The International Journal of Clinical Practice, 67(12), 1311–1316.

Rebar, A. L., Stanton, R., Geard, D., Short, C., Duncan, M. J., & Vandelanotte, C. (2015). A meta-meta-analysis of the effect of physical activity on depression and anxiety in non-clinical adult populations. Health Psychology Review, 9(3), 366–378.

Ribeiro, J. D., Silva, C., & Joiner, T. E. (2014). Overarousal interacts with a sense of fearlessness about death to predict suicide risk in a sample of clinical outpatients. Psychiatry Research, 218(1–2), 106–112.

Ribeiro, J. D., Huang, X., Fox, K. R., & Franklin, J. C. (2018). Depression and hopelessness as risk factors for suicide ideation, attempts and death: Meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 212(5), 279–286.

Rudd, M. D., Berman, A. L., Joiner, T. E., Nock, M. K., Silverman, M. M., Mandrusiak, M., Van Orden, K., & Witte, T. (2006). Warning signs for suicide: Theory, research, and clinical applications. Suicide and Life-threatening Behavior, 36(3), 255–265.

Sabo, D., Miller, K. E., Melnick, M. J., Farrell, M. P., & Barnes, G. M. (2005). High school athlete participation and adolescent suicide. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 40, 5–23.

Schuch, F. B., Vancampfort, D., Richards, J., Rosenbaum, S., Ward, P. B., & Stubbs, B. (2016). Exercise as a treatment for depression: A meta-analysis adjusting for publication bias. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 77, 42–51.

Siegmann, P., Willutzki, U., Fritsch, N., Nyhuis, P., Wolter, M., & Teismann, T. (2019). Positive mental health as a moderator of the association between risk factors and suicide ideation/behavior in psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatry Research, 273, 678–684.

Simon, T. R., Powell, K. E., & Swann, A. C. (2004). Involvement in physical activity and risk for nearly lethal suicide attempts. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 27, 310–315.

Stanley, I. H., Hom, M. A., Luby, J. L., Joshi, P. T., Wagner, K. D., Emslie, G. J., Walkup, J. T., Axelson, D. A., & Joiner, T. E. (2017). Comorbid sleep disorders and suicide risk among children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 95, 54–59.

Stubbs, B., Vancampfort, D., Rosenbaum, S., Firth, J., Cosco, T., Veronese, N., Salum, G. A., & Schuch, F. B. (2017). An examination of the anxiolytic effects of exercise for people with anxiety and stress-related disorders: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 249, 102–108.

Taliaferro, L. A., Eisenberg, M. E., Johnson, K. E., Nelson, T. F., & Neumark-Sztainer, D. (2011). Sport participation during adolescents and suicide ideation and attempts. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 23, 3–10.

Teismann, T., & Brailovskaia, J. (2020). Entrapment, positive psychological functioning and suicide ideation: A moderation analysis. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 27, 34–41.

Teismann, T., Forkmann, T., Glaesmer, H., Egeri, L., & Margraf, J. (2016). Remission of suicidal thoughts: Findings from a longitudinal epidemiological study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 190, 723–725.

Teismann, T., Forkmann, T., Brailovskaia, J., Siegmann, P., Glaesmer, H., & Margraf, J. (2018). Positive mental health moderates the association between depression and suicide ideation: A longitudinal study. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 18, 1–7.

Teismann, T., Brailovskaia, J., & Margraf, J. (2019). Positive mental health, positive affect and suicide ideation. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 19, 165–169.

Twenge, J. M., Joiner, T. E., Rogers, M. L., & Martin, G. N. (2018). Increases in depressive symptoms, suicide-related outcomes, and suicide rates among US adolescents after 2010 and links to increased new media screen time. Clinical Psychological Science, 6(1), 3–17.

Vancampfort, D., Hallgren, M., Firth, J., Rosenbaum, S., Schuch, F. B., Mugisha, J., Probst, M., Van Damme, T., Carvalho, A. F., & Stubbs, B. (2018). Physical activity and suicidal ideation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 225, 438–448.

Voss, C., Ollmann, T. M., Miché, M., Venz, J., Hoyer, J., Pieper, L., Höfler, M., & Beesdo-Baum, K. (2019). Prevalence, onset, and course of suicidal behavior among adolescents and young adults in Germany. JAMA Network Open, 2(10), e1914386–e1914386.

World Health Organization. (2014). Preventing suicide. Aglobal imperative. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization Press.

Wunsch, K., Kasten, N., & Fuchs, R. (2017). The effect of physical activity on sleep quality, well-being, and affect in academic stress periods. Nature and Science of Sleep, 9, 117–126.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The study was funded by the Alexander von Humboldt Professorship warded to Jürgen Margraf by the Alexander von Humboldt-Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article was revised due to Retrospective Open Access.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Brailovskaia, J., Teismann, T. & Margraf, J. Positive mental health mediates the relationship between physical activity and suicide-related outcomes: a three-year follow-up study. Curr Psychol 41, 6543–6548 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01152-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01152-x