Abstract

Religion is a significant predictor of self-regulatory processes. Procrastination has been described as the very essence of self-regulatory failure. In this study, we examined the relationship between religiousness and procrastination, with locus of control and styles of prayer playing mediating roles. These relationships were tested using data from 196 students. We applied the Centrality of Religiosity Scale, Levenson’s Locus of Control Scale, the God Control Scale, the Content of Prayer Scale, and the Behavioral Procrastination Scale. The results showed that: God control fully mediates the effects of ideology and intellect on procrastination; internal control fully mediates the effect of public prayer and religious experience on procrastination; and passive style of prayer was a mediator in the relationship between centrality of religion and procrastination. Our findings suggest that religious people may give up internal control, believing that their matters are in God’s hands. Being subject to God’s power provides them with a replacement form of control, which reduces problems of self-regulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Religion is a significant predictor of self-regulatory processes (McCullough and Carter 2013). A more specific concept, which plays a significant role in self-regulatory processes, is self-control (McCullough and Willoughby 2009). Procrastination has been described as the quintessence of self-regulatory failure (Rebetez et al. 2018; Steel 2007). Our study was designed to clarify the relationship between religion and procrastination. Specifically, we aimed to investigate the mechanism underlying the relationship between centrality of religion to a person’s life and the relationship between religion and procrastination – specifically, whether locus of control and styles of prayer can be mediators in these relationships.

Procrastination is voluntarily delay an intended course of action despite expecting to be worse off for the delay (Steel 2010). Estimates indicate that 80% to 90% of college students engage in procrastination, 75% consider themselves procrastinators, and 50% procrastinate problematically. Procrastination is also widespread in the general population, chronically affecting approximately 15% to 20% of adults. A smaller percentage of procrastinators in an adult sample might be related to the fact that the ability to overcome procrastination increases with age and practice in performing tasks (Steel 2007).

There have been many attempts to define the reasons why people procrastinate or keep procrastinating despite knowing its negative consequences. Steel (2007) indicated that the potential causes of procrastination can be reduced to two groups of factors: task characteristics and individual differences. Among the task characteristics, task aversiveness and task delay are strong predictors of procrastination. People tend to procrastinate when the task is aversive or when rewards are delayed. The importance of task aversiveness in triggering procrastination has been confirmed for different types of tasks including personal projects, daily tasks, academic tasks, and job search behaviors. Among individual differences, strong and consistent predictors of procrastination are self-efficacy, impulsiveness, and conscientiousness as well as its facets of self-control, distractibility, organization, and achievement motivation. Outcomes of procrastination refer to the expected effects on utility, specifically a poorer mood and worse performance. Procrastinators tend to be worse off in terms of both how they feel and what they achieve (Steel 2007).

Christian teaching does not refer to procrastination directly, but the Bible commends hard work and warns against indolence (e.g. Proverbs 12:24). Christians should be supremely motivated to be diligent in their work, since they are ultimately serving God. On the other hand, the Bible enjoins Christians to trust in the Lord rather than to rely on their own understanding or abilities (e.g. Proverbs 3:5, 16:3). Thus, religion might help people to form appropriate intentions that can then be translated into effective action, but it can also inhibit self-regulation, discouraging people from using personal resources to solve problems and prompting them to turn them over to God instead (McCullough and Carter 2013). One of the most common stereotypes is that religion is simply a form of denial and, in terms of the way situations can be handled, religion is passive or avoidant (Pargament 1997). Consequently, religious people are thought to be less productive and less effective than non-religious people, because they resign from some activities or postpone them, awaiting God’s intervention.

Examining the relationship between religion and procrastination requires one to realize that religion is a complex construct. Drawing from the distinction between substantive and functional approaches to religion (Hill and Edwards 2013), the present study included a substantive approach and focuses on motivational (e.g., centrality of religion) and structural aspects (e.g., religious beliefs, public or private prayer) of religion (cf. Huber 1996, 2003). The motivational aspect draws on the typology of intrinsic and extrinsic religious orientation (Allport and Ross 1967). The structural aspect includes five dimensions of religion, separated according to Stark and Glock (1970): intellectual, ideological, ritualistic (private and public practice), and experiential.

One mechanism through which religion can influence procrastination is via people’s beliefs about the extent to which they are personally in control of their lives. Many researchers have confirmed positive relationships between religiosity and self-control (e.g. Abar et al. 2009; Desmond et al. 2013; McCullough and Willoughby 2009). McCullough and Willoughby (2009) reviewed the research that examined the associations of measures of religiousness with measures of general self-control. Of the 12 studies they carried out, 11 confirmed positive associations between religiousness and self-control. For instance, self-rated religiousness (Desmond et al. 2013) and intrinsic religious orientation (Abar et al. 2009; French et al. 2008) were associated with higher self-control. Relationships between religion and self-control were sought also at the level of personality. Higher agreeableness and conscientiousness – personality traits that subsume aspects of self-control – tend to be positively correlated with measures of religion (Saroglou 2002, 2010). Religion is strongly linked with goals and values, which involve self-discipline and low level of self-indulgence. Religious people preferred tradition and conformity – including qualities such as being responsible, helpful, self-disciplined, and polite – and rejected hedonism and stimulation (Saroglou et al. 2004). A few studies reported that the level of parental religiosity was a significant predictor of their children’s self-control (e.g. Bartkowski et al. 2008). Religion can strengthen self-control in three ways: it can increase volitional efficiency, control emotional regulation, and provide meaning to life. These processes are automated and result from the system of religious beliefs (Fishbach et al. 2003).

People may attribute control to themselves, other people, or may think that their life is a work of chance or is in God’s hands – this is why they have a different sense of locus of control. Researchers studying control have developed a framework embracing interpretative, predictive, and vicarious types of control (Spilka and Ladd 2013). Rotter (1966) defined two polarized sides of locus of control: internal and external. People who have an internal locus of control believe that behavioral outcomes depend on their own actions. In contrast, having an external locus of control corresponds to believing that outcomes depend on external reasons. Levenson (1973) extended the sense of external control, including the belief in coincidences or other mighty factors or people, whereas Kopplin (1976) included the belief in God exercising control. Empirical research investigating the relations between religious orientation and locus of control suggests that intrinsic religious orientation correlated positively with internal and negatively with external locus of control. Extrinsic religious orientation correlated negatively with internal and positively with external locus of control (Cirhinlioğlu and Özdikmenli-Demir 2012).

The other mechanism through which religion could influence procrastination is via people’s prayer. The belief that prayer can have a regulatory function has been confirmed in other studies (e.g. Cahn and Polich 2006; McNamara 2002). Pargament and co-workers (Pargament et al. 1988) separated three types of attitudes in people who address God in their prayers: (1) passive, in which people shrug off responsibility from themselves and ask God for help, and then say “everything is in God’s hands”; (2) cooperative, in which people assume that they cooperate with God on solving the problem; and (3) self-directing, in which people “talk” to God and discuss the problem with their Interlocutor, but think that they should solve the problem themselves. The self-directing attitude comforts them and confirms their belief that they are right in their attitude, with God acting as a therapist who strengthens their personal sense of control.

There are two empirical findings that confirmed religion as a predictor of procrastination. Namian and Hosseinchari (2012) found that the ethical component of religious orientation was a negative predictor of academic procrastination. They also found that students who were studying religion-relevant disciplines scored lower on a measure of academic procrastination than those studying in religion-irrelevant disciplines. Nasab and Mohammadi-Aria (2015) found that religious strategies predicted academic procrastination. Cognitive, behavioral and emotional religious strategies were all negatively correlated with academic procrastination. One could argue that religious students tend to fulfill their religious obligations in a timely manner and that this habit of punctuality and responsible behavior generalizes to academic affairs, making them more conscientious in academic matters than their non-religious peers. Drawing upon these results we expected centrality of religion to be a factor that reduces procrastination tendency. Our first hypothesis refers to the negative correlation between centrality and procrastination. Moreover, we aimed to examine which dimensions of religion are the best procrastination predictors. Both studies investigated direct links between religion and procrastination in samples of Muslim students, but neither examined underlying processes. The aim of our study was to analyze the mechanism underlying the relationship between centrality of religion to a person’s life and of a relationship between religion and procrastination.

In our second hypothesis, we assumed that locus of control is a mediator of the relationship between religion and procrastination. We tested four sources of the sense of control – internal, powerful others, chance/fate control, and God control. We hypothesized that, in a way, religious people resign from internal, powerful others, and chance/fate control in favor of the belief in God control. By making themselves subject to God’s power, they earn the sense of some kind of alternative control (Spilka and Ladd 2013). This is why we predicted that high centrality of religion will reduce internal, powerful others, and chance/fate control and increase the sense of God control, whereas God control will diminish the tendency to procrastinate. We examined the predictive role of five dimensions of centrality in explaining procrastination through their effects on locus of control.

Our third hypothesis relies on the assumption that those who believe in God pass control over their lives to God when they pray. We tested three styles of prayer—passive, cooperative, and self-directing—which are basically concerned with matters of personal control (Pargament et al. 1988), as mediators in the relationship between centrality of religion and procrastination. In particular, we hypothesized that individuals with a higher centrality of religion who say more self-directing and collaborative prayers are less prone to procrastinate, whereas people who say more passive prayers are more prone to procrastinate.

Method

Participants

Participants were 196 students (116 females and 80 males). We decided to recruit a student sample, because procrastination is commonly observed in academic activities such as writing papers, studying for examinations and completing academic assignments (Batool et al. 2017). The mean age of the sample was 22.4 years (SD = 1.45) and the most represented religious affiliation was Roman Catholic (91.3%). Table 1 shows baseline demographic characteristics for all participants. Based on the results for the whole group we established correlations between centrality of religion, locus of control, and procrastination. Where styles of prayer were tested as mediators, it was necessary to include only those students who pray on a regular basis. The inclusion criterion for this group was the answer to a question: How often do you usually pray? Participants responded to this item using a scale ranging from 1 (Never) to 9 (Several times a day). Those who declared that they prayed at least once a day were included in the analysis. Those who prayed less than once a day were excluded from the analysis. Eighty-one of the 196 potential participants (52 women and 29 men) met this criterion.

Measures

Measures were scored by averaging across items. All descriptive statistics and internal reliability estimates are available in Table 2.

Centrality of Religion

We used the Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS) by Huber and Huber (2012) to assess five dimensions of religiosity: intellect (e.g., How interested are you in learning more about religious topics?), ideology (e.g., To what extent do you believe that God or something divine exists?), private practice (e.g., How important is personal prayer for you?), public practice (e.g., How often do you take part in religious services?), and religious experience (e.g., How often do you experience situations in which you have the feeling that God or something divine intervenes in your life?). The total score – centrality – is the sum of the subscales’ results. The response options for intellect, ideology, and religious experience were from 1 (Not at all/never) to 5 (Very much so/very often). For private and public practice, as they are undertaken regularly in most religious traditions and are easily accessible in frequency format, objective frequencies were asked. The response options for private practice were from 1 (Never) to 9 (Several times a day), and for public practice from 1 (Never) to 8 (More than once a week). The objective frequencies were recoded into five levels of subjective frequencies. The Polish version of the CRS showed appropriate psychometric properties (Zarzycka 2007, 2011). Cronbach’s alpha was satisfactory in this sample (Table 2).

Locus of Control

To assess locus of control, we administered the 18-item Locus of Control Scale (LOC) by Levenson (1973). This scale measures how much an individual believes that events are caused by external factors (e.g., chance/fate or powerful others) or internal factors (i.e., their own behavior or actions). Responses were on a Likert-type rating scale from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 6 (Strongly agree). High scores indicated an internal locus of control. A Polish version of the LOC scale was developed by Łucki (cf. Drwal et al. 1995). Cronbach’s alpha was satisfactory in the present sample (Table 2).

God Control

We assessed the individual’s sense of control by God using the God Control Scale (GCS) by Kopplin (1976). Participants responded to eight items on a Likert-type rating scale from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 6 (Strongly agree). A Polish version of the GCS scale was developed by Łucki (cf. Drwal et al. 1995). Cronbach’s alpha was excellent in the present sample (Table 2).

Prayer

We assessed the cooperative, passive, and self-directing styles of prayer (CoP) using 12 items adapted from Huber (2008). Participants indicated how often the following content appears in their prayers: e.g., asking God to solve a problem for them; a case in which you decided; asking God for help in handling a certain matter. The response options were from 1 (Never) to 5 (Very often). The Polish version of the CoP showed appropriate psychometric properties (Bartczuk, Zarzycka, in print). Cronbach’s alpha was satisfactory in this sample (Table 2).

Behavioral Procrastination

We assessed behavioral procrastination using the Behavioral Procrastination Scale (BPS) by Jaworska-Gruszczyńska (2016). This scale assesses the tendency to delay the beginning and/or the completion of tasks in academic settings. The BPS has a hierarchical structure and consists of two primary factors: behavioral procrastination and unpunctuality. Behavioral procrastination includes four secondary factors: organization, strength of will, awareness of procrastination, and procrastination-trait. In the present study, we applied only the general indicator, which measures behavioral procrastination. Respondents rated their agreement with 33 items, such as I often delay getting down to necessary tasks and When I am bound by deadlines, I keep waiting with completing the task until the last minute, on a scale from 1 (I’m not at all like this) to 5 (This is exactly me). The Polish version of the BPS showed appropriate psychometric properties (Jaworska-Gruszczyńska 2016). Cronbach’s alpha was satisfactory in this sample (Table 2).

Demographics

The survey assessed gender, age, marital status, place of residence, and religious affiliation.

Study Design

This was a cross-sectional design. To establish whether the key constructs – centrality of religion, locus of control, prayer, and behavioral procrastination – were correlated, we calculated Pearson’s correlations between the CRS, LOC, GCS, CoP, and BPS scales, as well as between their subscales. Next, two series of regression mediation analyses were conducted. In both mediation models, centrality of religion and its five dimensions were subsequently examined as predictors of behavioral procrastination. Internal control, God control, powerful others, and chance/fate were tested as parallel mediators in the first series of mediation analyses. Figure 1 shows the general mediation model.

Diagram of the general mediation model with locus of control as mediators. Note. c` direct effect of predictor on outcome while controlling for the mediator; a1, a2, a3, a4 effect of the predictor on the mediator; b1, b2, b3, b4 effect of the mediator on the outcome; ab indirect effects of predictor on outcome through the mediator

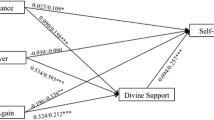

The cooperative, passive, and self-directing styles of prayers were tested as mediators in the second series of mediation analyses. Figure 2 shows the general mediation model.

All mediation analyses were performed using macro PROCESS (Hayes 2018). PROCESS is based on a regression-based path-analytic framework and estimates indirect effects and bias-corrected confidence intervals (CIs) using bootstrapping method. An indirect effect is considered significant when the CI does not include zero. The analyses were based on 5000 bootstrapping samples. Bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals were presented for all indirect effects. The correlation analysis was performed using SPSS version 24.0.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The mean scores on the CRS subscales (excluding Intellect), the Internal Control and Powerful Others subscales on LOC, God Control on GCS, the Cooperative and Self-Directing subscales on CoP, and Behavioral Procrastination on BPS were negatively skewed (ranging from −0.17 to −1.24), with a larger number of high values. The mean scores on the Intellect subscale of the CRS and the Passive subscale of the CoP were positively skewed (ranging from 0.01 to 0.07), with more low values. The skewness was not strong enough, so it can be ignored. It should be noted that the result in the Ideology subscale was above 4, whereas in the Intellect and Experience subscales the results were below 3 (Table 2). Such observations are frequent in Polish samples (e.g., Bartczuk et al. 2013; Zarzycka 2009; Zarzycka and Tychmanowicz 2015) and suggest that religiosity in the Polish is rather more ideological than reflective or personally experienced.

Correlations

Table 2 shows the Pearson correlation coefficients between the variables measured in this study. There are very high positive correlations between centrality – the general score and its five dimensions – and God control. Centrality correlated negatively with internal control, powerful others, and chance/fate. Internal control correlated negatively with behavioral procrastination, whereas chance/fate control was connected positively with procrastination. Centrality of religion correlated positively with the cooperative, self-directing, and passive styles of prayer. No significant correlations emerged between centrality and behavioral procrastination.

Main Analysis

We examined locus of control and styles of prayer as mediators in the relationship between centrality of religion and behavioral procrastination.

Centrality of Religion–Locus of Control–Behavioral Procrastination Mediation Analyses

We conducted a series of regression mediation analyses with internal, God, chance/fate, and powerful others control as parallel mediators in the centrality–behavioral procrastination relationship. Table 3 shows all the significant results of the mediation analyses.

There was a significant indirect effect of centrality of religion through internal control on behavioral procrastination. Centrality significantly reduced internal control, which in turn increased the tendency to procrastinate.

Intellect and ideology predicted behavioral procrastination through their effects on God control. Both high interest in religious matters and strong religious beliefs increased God control, which in turn decreased behavioral procrastination. Intellect also predicted behavioral procrastination through its effect on chance/fate. High interest in religion decreased chance/fate control, which in turn decreased behavioral procrastination.

Religious experience and public prayer affected behavioral procrastination through their effects on internal control. Both religious experience and public practice decreased internal control, which in turn increased the tendency to procrastinate. After controlling the mediators, all direct effects of centrality of religion, as well as its dimensions on behavioral procrastination, were insignificant.

Centrality of Religion–Styles of Prayer–Behavioral Procrastination Mediation Analyses

Finally, we conducted a series of regression mediation analyses with the cooperative, passive, and self-directing styles of prayer as mediators in the centrality–behavioral procrastination relationship. Centrality of religion was positively related to cooperative (a1 = .88, p < .001), passive (a2 = .66, p < .001), and self-directing (a3 = .61, p < .001) styles of prayer. However, passive prayer was the only significant mediator in the relationship between centrality of religion and behavioral procrastination. Centrality increased the tendency to procrastinate through its effect on passive prayer. Passive prayer was also the only significant mediator in the relationship between the four dimensions of centrality – intellect, ideology, religious experience, and public prayer – and behavioral procrastination. All dimensions of centrality increased the tendency to procrastinate through their effects on passive prayer; see Table 3 for the significance of the mediation analyses.

Discussion

Our research suggests that the relationship between centrality of religion and procrastination is not direct. The correlations between the centrality of religion (and its dimensions) and behavioral procrastination were insignificant, and thus, our first hypothesis was not confirmed. This result is not in line with the results, which suggest that religion is a negative predictor of procrastination (Namian and Hosseinchari 2012; Nasab and Mohammadi-Aria 2015). We think that the difference we observed might result from accounting for different approaches to religion. Namian and Hosseinchari (2012) analyzed the ethical component of religion while Nasab and Mohammadi-Aria (2015) analyzed religious coping strategies. Both represent functional approaches to religion, describing how religious activities function in an individual’s life. Centrality, which indicates the importance of religion, is a dispositional measure (Hill and Edwards 2013), and thus it might affect an individual’s functioning indirectly, shaping religious activities or strategies that people use in everyday situations. This interpretation is supported by the results of our research, which indicate that the mechanism of the relationship between the centrality of religion and procrastination is indirect. We did observe that locus of control and style of prayer are mediators in the relationship between centrality of religion and procrastination. These results are in line with the claim supported by McCullough et al. (2000) that self-control may help to explain religion’s well-established associations with different measures of behavior—outcomes that other research has consistently linked to high self-control (McCullough and Carter 2013).

Our second hypothesis, which predicted that a high centrality of religion will reduce internal, powerful others control, and chance/fate control, while increase the sense of locus of control in God, which, in turn, reduce the tendency to procrastinate was partially confirmed. Cognitive dimensions of religiousness—ideology and intellect—reduce the tendency to procrastinate, because they strengthen the belief that events are part of God’s plan and subject to His control. The ideological dimension, which involves one’s beliefs, and unquestioned convictions regarding the existence and the essence of a transcendent reality (Huber and Huber 2012), is the strongest predictor of the sense of locus of control in God. The intellectual dimension, which involves thinking or learning about religious issues, reduces the tendency to procrastinate, not only because it strengthens the belief that God controls events, but also because it weakens the conviction that events are a matter of chance or fate. A strong belief that God “takes care of the world,” as in the view of Providence, therefore strengthens the conviction that human lives are parts of God’s plan and fosters motivation for the active fulfillment of individual responsibilities related to God. This is in line with research suggesting that a sense of agency and control provided by religion correlates with a collaborative relationship with God (Krause 2005; Pargament et al. 1988). One may think that the question of which control attributions we formulate depends on the general religious cognitive scheme, which describes the way we refer to the supernatural reality—it plays an important role in self-regulatory processes (Spilka and Ladd 2013).

However, public prayer and religious experience do not increase the sense of locus of control in God, but they weaken internal control instead. As a result, this might foster a tendency to procrastinate. Interestingly, both public practice and religious experience involve the social aspects of religion. The public practice dimension suggests how much individual religiosity is rooted socially (Huber and Huber 2012). Religious rituals are performed according to rules set down by others in the past that are not at all open to the motivated intentions or the self-directed agency of the individuals performing them (Boyer 2001; Idler 2013). Marshall (2002) claimed that participating in rituals can lead an individual to experience feelings of deindividuation, or the loss of a sense of a separate self, and a concomitant sense of unity with the group. Religious experience also involves the social aspect of religion. According to Stark and Glock (1970, p. 126), religious experience can be defined as “an encounter—some sense of contact—between themselves and some supernatural consciousness”. The divinity and the individual can be considered a pair of actors involved in a social encounter and the relationship between them can be ordered in terms of social distance. Huber and Huber (2012) claimed that the experience of transcendence takes two basic forms: one-to-one experience, which corresponds to a dialogical spirituality pattern, and experience of being at one, corresponding to a participative pattern. Both refer to “some kind of direct contact to an ultimate reality” (Huber and Huber 2012, p. 714). Involvement in the social aspects of religion may therefore be related to a sense of the certain deindividuation of the self and a resignation from personal control. This is a phenomenon reported by Idler (2013), who pointed out that participating in a religious ritual is indicative of submission to a higher authority, with the deindividuation of the self in the midst of a group, however, it leads to emotionally satisfying feelings of being surrounded, protected, and comforted. Our findings make it possible for us to conclude that deep roots in social aspects of religion may weaken the sense of a personal locus of control, and, as a result, foster procrastination.

Tu conclude, as cognitive aspects of religion strengthen the sense of locus of control in God, and social aspects of religion reduce internal locus of control, we may assume that religious people may be relinquishing a sense of control and personal efficacy to their God. In its place, they attain a form of vicarious control by aligning themselves with God’s power. The belief in a benevolent controlling God may be equivalent to sense of personal control (Spilka and Ladd 2013). Despite resigning from personal control, over events may lead to procrastination, and being subject to God’s power provides some sense of replacement control which reduces difficulties in terms of self-regulation. A theory of compensatory control has been confirmed in some studies (e.g. Kay et al. 2008, 2010).

The third hypothesis was built upon the idea that faithful people transfer control over their lives to God when they pray. Particularly, we hypothesized that individuals with a higher centrality of religion, and who say more self-directing and collaborative prayers are less prone to procrastinate, while people who say more passive prayers are more prone to procrastinate. This hypothesis was confirmed only partially. Although a high centrality of religion (and its dimensions) is related directly to each of the three styles of prayer, it is only passive prayer that leads to procrastination. Moreover, mediation effects are significant only in those who pray frequently. People with a high centrality of ideology, intellect, religious experience, and public practice, who pray at least once a day and ask God for help in their prayers, but leave their matters in God’s hands, are prone to procrastinate. As this result remains unchanged for each of centrality of religion dimensions, we may treat it as non-specific. Potentially negative consequences of prayer style, which are centered around shrugging off their responsibility on God, were suggested by Bade and Cook (2008), who found that it is related with a lower control over fear. Other prayer styles—self-directing and collaborative—failed to mediate the relationship between centrality of religion and procrastination. Frequent prayer in those with high religious involvement does not necessarily lead to procrastination, provided that the one who prays assumes that they cooperate with God in solving the problem or solve the problem with God, continuing to believe that they themselves should be involved in its solution. Interestingly, as it expresses basic and irreducible forms of addressing oneself to transcendence, private practice involving both prayer and meditation (Huber and Huber 2012), does not predict procrastination through its effect on the passive style of prayer. We suppose that this may be caused by the low variance of results on the private practice subscale in people who practice prayer at least once a day.

The main limitation of this study was that the majority of the sample was of one religion, which greatly limits the generalizability of the results. Replication in samples from other religious backgrounds is needed. The analysis, in which we assessed self-directing, passive and collaborative styles of prayer as potential mediators of the relationship between religion and procrastination, was carried out on a small sample of people who prayed at least once a day, most of whom were women. Because of the small sample size our results must be regarded as preliminary. In addition, the inclusion criterion was frequent private prayer, so our results cannot be generalized to people who practice various forms of public prayer. It should also be emphasized that the cross-sectional, non-experimental design limits our ability to make causal interpretations of the findings.

This is the first study to examine locus of control and styles of prayer as mediating factors in the relationship between centrality of religion and procrastination. Our findings suggest that, although socially rooted dimensions of religiousness can weaken the internal locus of control, cognitive dimensions can increase God control and, consequently, decrease the manifestations of self-regulatory difficulties that accompany procrastination. This research shows that it is necessary to include the multidimensionality of religion when verifying its functions in self-regulatory processes.

References

Abar, B., Carter, K. L., & Winsler, A. (2009). The effects of maternal parenting style and religious commitment on self-regulation, academic achievement, and risk behavior among African-American parochial college students. Journal of Adolescence, 32(2), 259–273.

Allport, G. W., & Ross, M. J. (1967). Personal religious orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 5(4), 432–443.

Bade, M. K., & Cook, S. W. (2008). Functions of Christian prayer in the coping process. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 47(1), 123–133.

Bartczuk, R. P., Zarzycka, B., & Wiechetek, M. (2013). Struktura wewnętrzna polskiej adaptacji Skali Przekonań Postkrytycznych [the internal structure of the polish adaptation of the post-critical belief scale]. Roczniki Psychologiczne/Annals of Psychology, 16(3), 539–561.

Bartkowski, J. P., Xu, X., & Levin, M. L. (2008). Religion and child development: Evidence from the early childhood longitudinal study. Social Science Research, 37(1), 18–36.

Batool, S. S., Khursheed, S., & Jahangir, H. (2017). Academic procrastination as a product of low self-esteem: A mediational role of academic self-efficacy. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 32(1), 195.

Boyer, P. (2001). Religion explained: The evolutionary origins of religious thought. New York: Basic Books.

Cahn, B. R., & Polich, J. (2006). Meditation states and traits: EEG, ERP, and neuroimaging studies. Psychological Bulletin, 132(2), 180–211.

Cirhinlioğlu, F. G., & Özdikmenli-Demir, G. (2012). Religious orientation and its relation to locus of control and depression. Archive for the Psychology of Religion, 34(3), 341–362.

Desmond, S. A., Ulmer, J. T., & Bader, C. D. (2013). Religion, self control, and substance use. Deviant Behavior, 34(5), 384–406.

Drwal, R. Ł., Brzozowski, P., & Oleś, P. (1995). Adaptacja kwestionariuszy osobowości: Wybrane zagadnienia i techniki [adaptation of personality questionnaires: Selected issues and techniques]. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN.

Fishbach, A., Friedman, R. S., & Kruglanski, A. W. (2003). Leading us not into temptation: Momentary allurements elicit overriding goal activation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), 296–309.

French, D. C., Eisenberg, N., Vaughan, J., Purwono, U., & Suryanti, T. A. (2008). Religious involvement and the social competence and adjustment of Indonesian Muslim adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 44(2), 597–611.

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). New York: The Guilford Press.

Hill, P. C., & Edwards, E. (2013). Measurement in the psychology of religiousness and spirituality: Existing measures and new frontiers. In K. I. Pargament, J. J. Exline, & J. W. Jones (Eds.), APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality (Vol 1): Context, theory, and research (pp. 51–77). Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association.

Huber, S. (1996). Dimensionen der Religiosität: Skalen, Messmodelle und Ergebnisse einer empirisch orientierten Religionspsychologie. Bern: Verlag Hans Huber.

Huber, S. (2003). Zentralität und Inhalt: ein neues multidimensionales Messmodell der Religiosität. Opladen: Leske + Budrich.

Huber, S. (2008). Der Religiositäts-Struktur-Test (RST). Systematik und operationale Konstrukte [The Religiosity Structure Test (RST). Classification and operationalization of the construct]. In W. Gräb & L. Charbonnier (Eds.), Individualisierung und die pluralen Ausprägungsformen des Religiösen. Studien zu Religion und Kultur [individual and common expressions of religiosity. Studies on religion and culture] (pp. 109–143). Münster: Lit-Verlag.

Huber, S., & Huber, O. W. (2012). The centrality of religiosity scale (CRS). Religions, 3(3), 710–724.

Idler, E. L. (2013). Rituals and practices. In K. I. Pargament, J. J. Exline, & J. W. Jones (Eds.), APA handbooks in psychology. APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality (Vol. 1): Context, theory, and research (pp. 329–347). Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association.

Jaworska-Gruszczyńska, I. (2016). Prokrastynacja – Struktura konstruktu a stosowane skale pomiarowe [procrastination - structure of the construct and applied measuring scales]. Testy psychologiczne w praktyce i badaniach [Psychological tests in practice and research], 2(1), 36–59.

Kay, A. C., Gaucher, D., Napier, J. L., Callan, M. J., & Laurin, K. (2008). God and the government: Testing a compensatory control mechanism for the support of external systems. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(1), 18–35.

Kay, A. C., Gaucher, D., McGregor, I., & Nash, K. (2010). Religious belief as compensatory control. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14(1), 37–48.

Kopplin, D. (1976). Religious orientations of college students and related personality characteristics. Washington D.C: Presented at the American Psychological Association.

Krause, N. (2005). God-mediated control and psychological well-being in late life. Research on Aging, 27(2), 136-164.

Levenson, H. (1973). Multidimensional locus of control in psychiatric patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 41(3), 397–404.

Marshall, D. A. (2002). Behavior, belonging, and belief: A theory of ritual practice. Sociological Theory, 20(3), 360–380. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9558.00168.

McCullough, M. E., & Carter, E. C. (2013). Religion, self-control, and self-regulation: How and why are they related? In K. I. Pargament, J. J. Exline, & J. W. Jones (Eds.), APA handbooks in psychology. APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality (Vol. 1): Context, theory, and research (pp. 123–138). Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association.

McCullough, M. E., & Willoughby, B. L. (2009). Religion, self-regulation, and self-control: Associations, explanations, and implications. Psychological Bulletin, 135(1), 69–93.

McCullough, M. E., Hoyt, W. T., Larson, D. B., Koenig, H. G., & Thoresen, C. (2000). Religious involvement and mortality: A meta-analytic review. Health Psychology, 19(3), 211–222.

McNamara, P. (2002). The motivational origins of religious practices. Zygon® Journal of Religion and Science, 37(1), 143–160.

Namian, S., & Hosseinchari, M. (2012). Explaining procrastination in university students based on locus of control and religious beliefs. Journal of Educational Psychology Studies, 14(8), 99–126.

Nasab, N. F., & Mohammadi-Aria, D. A. (2015). The predictive role of religious beliefs and psychological hardiness in academic procrastination of high school students (Dalgan). International Research Journal of Applied and Basic Sciences, 9(7), 1082–1087.

Pargament, K. I. (1997). The psychology of religion and coping. New York: The Guilford Press.

Pargament, K. I., Kennell, J., Hathaway, W., Grevengoed, N., Newman, J., & Jones, W. (1988). Religion and the problem-solving process: Three styles of coping. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 27(1), 90–104.

Rebetez, M. M. L., Rochat, L., Barsics, C., & Van der Linden, M. (2018). Procrastination as a self-regulation failure: The role of impulsivity and intrusive thoughts. Psychological Reports, 121(1), 26–41.

Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 80(1), 1–28.

Saroglou, V. (2002). Beyond dogmatism: The need for closure as related to religion. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 5(2), 183–194.

Saroglou, V. (2010). Religiousness as a cultural adaptation of basic traits: A five-factor model perspective. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14(1), 108–125.

Saroglou, V., Delpierre, V., & Dernelle, R. (2004). Values and religiosity: A meta-analysis of studies using Schwartz’s model. Personality and Individual Differences, 37(4), 721–734.

Spilka, B. & Ladd, K. L. (2013). The psychology of prayer. A scientific approach. New York: The Guilford Press.

Stark, R., & Glock, C. Y. (1970). American piety: The nature of religious commitment. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press.

Steel, P. (2007). The nature of procrastination: A meta-analytic and theoretical review of quintessential self-regulatory failure. Psychological Bulletin, 133(1), 65–94.

Steel, P. (2010). Arousal, avoidant and decisional procrastinators: Do they exist? Personality and Individual Differences, 48(8), 926–934.

Zarzycka, B. (2007). Skala Centralności Religijności Stefana Hubera [the polish version of S. Huber’s centrality of religiosity scale]. Roczniki Psychologiczne [Annals of Psychology], 10(1), 133–157.

Zarzycka, B. (2009). Tradition or charisma. Religiosity in Poland. In B. Stiftung (Ed.), What the world believes: Analysis and commentary on the Religion Monitor 2008 (pp. 201–222). Gütersloh: Verlag Bertelsmann Stiftung.

Zarzycka, B. (2011). Polska adaptacja Skali Centralności Religijności S. Hubera [polish adaptation of Huber’s centrality of religiosity scale]. In M. Jarosz (Ed.), Psychologiczny pomiar religijności [the psychological measurement of religiosity] (pp. 231–261). Lublin: Towarzystwo Naukowe KUL.

Zarzycka, B., & Tychmanowicz, A. (2015). Wiara i siła. Religijność w procesach koherencji [faith and strength: Religiosity in the coherence processes]. Lublin: Wydawnictwo UMCS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Zarzycka, B., Liszewski, T. & Marzel, M. Religion and behavioral procrastination: Mediating effects of locus of control and content of prayer. Curr Psychol 40, 3216–3225 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00251-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00251-8