Abstract

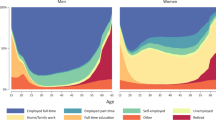

The deinstitutionalization of the life course and the increased agency of older people have dis/re-organized the temporal and spatial foundations of later life. Old age is becoming a time of transitions (and instability) as the labor market participation and the family arrangements of older people become more varied and as older people themselves become more mobile and healthier than ever before. Many studies exist that illustrate the improving health of the older population, their changing patterns of work, residence and family. However few studies have had the opportunity to look at how changes in one dimension are related to changes in others. The English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) is the largest study of older people in England and contains data on the demographic, employment, housing and health characteristics of over 11,000 people aged 50 and over. Using data from the first wave of data collection and baseline data from the Health Surveys for England (from which the ELSA sample was drawn) we have looked at transitions over five dimensions amongst the over 50s in England: transitions in labor market position, health status, marital status, household composition and residential location. Transitions in each of the dimensions were explored for the sample as a whole and then by sex and by cohort. Finally the relations between the different transitions were explored. The results show the majority of the sample experience change in at least one dimension and around one quarter in two dimensions. There were few differences between the sexes, although women were more likely to experience a change in labor market position. However there were differences between the age groups. Those in the older groups were less likely to experience transitions, apart from transitions in health statuses. Overall the data confirm that later life is a dynamic portion of the life course. These findings raise issues about our ability adequately to describe later life.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Beatty, C., & Fothergill, S. (2003). The detached male labour force. In P. Alcock, C. Beatty, S. Fothergill, R. Macmillan & S. Yeandle (Eds.), Work to welfare. How men become detached from the labor market. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 79–111.

Bernardi, B. (1985). Age class systems: Social institutions and polities based on age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Blakemore, K. (1999). International migration in later life: Social care and policy implications. Ageing and Society, 19, 761–74.

Bone, M. (1995). Trends in dependency among older people in England. London: Office of Population Census and Surveys.

Carter, S.B., & Sutch, R. (1996). Myth of the industrial scrapheap: A revisionist view of turn-of-the-century American retirement. The Journal of Economic History, 56, 5–38.

Choi, N.G. (2003). Determinants of self perceived changes in health status among pre and early retirement populations. International journal of aging and human development, 56, 197–222.

Coleman, P. & Bond, J. (1990). Ageing in the twentieth century. In J. Bond & P. Coleman (Eds.), An introduction to social gerontology. London: Sage.

Drentea, P. (2002). Retirement and mental health. Journal of Aging and Health, 14: 167–194.

Erens, B., & Primatesta, P. (1999). Health survey for England 1998. Volume 2: Methodology and documentation. London: HMSO.

Erens, B., Primatesta, P., & Prior, G. (2001). Health survey for England.. The health of ethnic minority groups 1999. Volume 2: Methodology and documentation. London: HMSO.

Espinoza, M.C., & Stallman, J.I. (1996). Seasonal migration of retirees: A review of the literature. Faculty paper series, FP97-2, Texas University.

Foner, N. (1984). Age and social change. In: D.I. Kertzer & J. Keith (Eds.), Age and anthropological theory. London: Cornell University Press.

Fraser, D. (2002). The Evolution of the British Welfare State. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gilleard, C., & Higgs, P. (2000). Cultures of ageing: Self, citizen and the body. Harlow: Prentice Hall.

Gilleard, C., & Higgs, P. (2005). Contexts of ageing: Class, cohort and community. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Gratton, B. (1996). The poverty of impoverishment theory. The economic well being of the elderly 1890–1950. The Journal of Economic History, 56, 39–61.

Guillemard, A.M., & Rein, M. (1993). Comparative patterns of retirement: Recent trends in developed societies. Annual Review of Sociology, 19, 469–503.

Gustafson, P. (2001). Retirement migration and transnational lifestyles. Ageing and Society, 21, 371–394.

Gustafson, P. (2002). Tourism and seasonal migration. Annals of Tourism Research, 29, 899–918.

Hareven, T.K. (1994). Aging and generational relations: A historical and life course perspective. Annual Review of Sociology, 20, 437–461.

Hyde, M., Hagberg, J., Oxenstierna, G., Theorell, T., & Westerlund, H. (2004). Bridges, pathways and valleys: Labour market position and risk of hospitalisation in a Swedish sample aged 55–63. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 32, 368–373.

Idler, E.L., & Benyamini, Y. (1997). Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 38 (1), 21–37.

Idler, E.L., & Kasl, S.V. (1995). Self-ratings of health: Do they also predict change in functional ability? Journal of Gerontology B series, 50 (6), S344–353.

Kohli, M., Rein, M., Guillemard, A.M., & van Gunsteren, H. (1991). Time for retirement. Comparative studies of early exit from the labor market. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Manton, K.G., & Gu, X. (2003). Changes in the prevalence of chronic disability in the United States black and non-black populations above age 65 from 1982 to 1999. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, 98, 6354–59

Mayer, K.U., & Schoepflin, U. (1989). The state and the lifecourse. Annual Review of Sociology, 15, 187–209.

McHugh, K.E., & Mings, R.C. (1996). The circle of migration: Attachment to place in aging. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 86, 530–585.

Mein, G., Martikainen, P., Hemingway, H., Stansfield, S., & Marmot, M. (2003). Is retirement good or bad for mental and physical health functioning? Whitehall II longitudinal study of civil servants. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 57, 46–49.

Parsons, D.O. (1991). Male retirement behaviour in the United States, 1930–1950. Journal of Economic History, 51, 657–674.

Phillipson, C. (2002). Transitions from work to retirement. Developing a new social contract. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Prior, G., Deverill, C., Malbut, K., & Primatesta, P. (2003). Health survey for England 2001. Volume 2: Methodology and documentation. London: HMSO.

Rowe, J.W., & Kahn, R.L. (1998). Successful aging. New York: Dell.

Taylor, R., Conway, L., Calderwood, L., & Lessof, C. (2003). Methodology. In M. Marmot, J. Banks, R. Blundell, C. Lassof, & J. Nazroo (Eds.), Health wealth and lifestyles of the older population in England. The 2002 English longitudinal study of ageing. London: IFS.

Thane, P. (2000). Old age in English history. Past experiences, present issues. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Torres, S. (2004). Making sense of the construct of successful ageing: The migrant experience. In S. O. Daatland and S. Biggs (Eds.), Ageing and diversity: Multiple pathways and cultural migrations. Bristol: Policy Press.

Townsend, P. (1963). The family life of old people. London: Pelican.

Wilson, G. (2001). Conceptual frameworks and emancipatory research in social gerontology. Ageing and Society, 21, 471–487

Warnes, A.M., King, R., Williams, A.M., & Patterson, C. (1999). The well-being of British expatriate retirees in southern Europe. Ageing and Society, 19, 717–740.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

His research interests are labor market exit and social participation in later life.

His research interests are social theory and social gerontology. He is the co-author of Cultures of Ageing: Self, Citizen and the Body with Chris Gilleard.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hyde, M., Higgs, P. The shifting sands of time: Results from the English longitudinal study of ageing on multiple transitions in later life. Ageing Int. 29, 317–332 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-004-1002-7

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-004-1002-7