Abstract

The 1997 reform in Turkey which extended compulsory schooling from 5 to 8 years provides an opportunity to estimate the returns to schooling in a middle-income country. The availability of a rich set of early labor market variables also provides an opportunity to assess mechanisms through which returns to schooling occur. I find quite small effects of compulsory schooling on earnings of men but large positive effects on earnings of women who work, without raising their overall low rate of labor force participation. In terms of mechanisms, I find that women who worked moved into higher skill and formal sector jobs, which involved more complicated tasks on average.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Tsai et al. (2009) examine the effect of 1968 compulsory schooling reform in Taiwan on gender disparities in employment. Although they do not examine the effect on earnings they investigate the effect on sector of employment and type of employment.

Earlier studies of returns to schooling focused on twins with different schooling levels or used family background as a control in the least squares estimation or as an instrument for schooling to deal with the potential endogeneity of schooling. Much of the former group suffers from the critique that the family background may be correlated with labor market outcomes through other ways than educational attainment.

Devereux and Hart (2009) reanalyse the dataset and find much smaller returns to schooling in Britain with no positive return for women and 3–4% return for men.

Using 2000 census data, I find that the share of vocational middle school graduates among those who drop out after the middle school was extremely small (2.5%) for individuals aged 20–24. So the change in the composition of middle school types is unlikely to affect the estimated outcomes significantly. Thus, I take years of education as a homogenous treatment.

The wording in the law was such that it required the fifth graders in 1997–1998 academic year to continue until the 8th grade. Considering the school starting age, that cohort corresponds to those who were born after 1986. Note that some individuals who were born in 1987 but started school early may not be exposed to the law, and someone who was born in 1986 and started school late may be exposed to the law. Individuals who turn 14 were allowed to drop out at the end of that academic year, regardless of the grade.

See Dulger (2004) for a detailed description of the compulsory schooling reform in Turkey.

One explanation for the assumption of negative covariance between marginal costs and marginal returns works through the family. Children of parents with high ability and high returns to education will partially inherit the high ability. Moreover, since the high ability parents earn high income, have better social network, have strong taste for schooling, and are not strongly affected by the social barriers, children will have less cost of schooling.

I would like to thank the staff in the Labor Force Statistics Department of Turkish Statistical Institute.

Table 9 in the Appendix shows the treated and untreated age-cohort groups.

Military service for male Turkish citizens is mandatory and unless postponed for educational or health purposes, men are recruited at the age of 20.

There would be a selection problem if the reform significantly affected college attendance since college graduates are allowed to postpone the recruitment after the graduation. In other words, the composition of men in the sample would vary across years. As a second check, I also provide the estimation results for the age interval 22–27 at the expense of smaller sample. The results are generally the same.

The low labor force participation among women makes it an interesting margin to examine. Later in the text, I find an insignificant effect of compulsory schooling on women’s labor force participation.

I also have a full set of results for the sample that includes those with missing year of birth variable. I impute the year of birth subtracting age from year of survey, and repeat the estimations for the whole sample. The results are nearly identical. I can provide those upon request.

Clustering at survey year or year of birth separately does not change the estimation results.

O’Brien (2000) shows that including full set of indicators for ages and survey years effectively controls for linear trends in year of birth. Yet, I already have the year of birth data and it varies within the same age and survey year, breaking the perfect collinearity with age and survey year indicators. Therefore I also include year of birth among control variables.

The fact that observations are obtained from different survey years should not affect the calculated middle school completion ratio since the definition of middle school degree is quite clear and invariant across survey years.

Similarly, when I look at the middle school completion ratio for individuals aged 20–29 using an untreated survey year I observe a linear trend across untreated years of birth. In this case, the fact that observations are obtained from different ages should not matter for middle school completion ratios since all individuals are above 20.

Double-shift schooling refers to the school system with two shifts. One group of students use the classrooms in the morning and another group of students use in the afternoon. A higher number of students can be taught in the same school building.

Oreopoulos (2006b) finds that a one-year increase in the number of mandatory school years is associated with a 0.18 increase in average grade attainment.

Since some observations in my sample are still enrolled in college, I estimate the effect of the reform on college enrollment and college graduation separately. I interpret the former as the upper bound since some individuals will drop out, and interpret the latter as the lower bound. Table 10 in the Appendix shows that all estimates are concentrated around zero, with negative lower bounds and positive upper bounds.

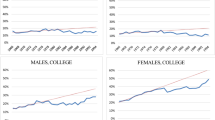

Table 12 in the Appendix presents the estimated returns to schooling for sample of individuals from urban areas as well. In all samples women have higher returns to schooling than men, and returns to schooling among men are around 0–2% and statistically insignificant. You can also find the OLS estimates of returns to schooling in Table 12.

The survey categorizes employed individuals into four groups: regular wage employees, employers, self-employed, and unpaid family worker. I combine the second and the third group under the self-employed category. Panel 1 and Panel 2 imply a decrease in the probability of being an unpaid family worker in the sample of men.

Informal employment constitutes 40% of the total employment in June 2012 (Turkstat).

Although the estimates are consistently positive across samples, the estimates are statistically insignificant in two of them. The estimated effect in the sample of men aged 22–27, and the estimated effect in the sample of women aged 20–29 are statistically insignificant.

In order to obtain task composition for each two-digit ISCO occupation category given in the survey data, I exploit two crosswalks. The first one matches DOT occupation categories to SOC 2000, and the second matches SOC 2000 categories to ISCO 88. The details of the match are provided in the Data Appendix.

References

Angrist JD, Imbens GW (1995) Two-stage least squares estimation of average causal effects in models with variable treatment intensity. J Am Stat Assoc 90:431–442

Angrist JD, Krueger AB (1991) Does compulsory school attendance affect schooling and earnings? Q J Econ 106(4):979–1014

Angrist JD, Imbens GW, Rubin DB (1996) Identification of causal effects using instrumental variables. J Am Stat Assoc 91:444–455

Aydemir A, Kirdar M (2013) Estimates of the return to schooling in a developing country: evidence from a major policy reform in Turkey. Working Paper no 51938. MPRA

Becker GS (1967) Human capital and the personal distribution of income; an analytical approach. Institute of Public Administration, Ann Arbor

Card D (1999) The causal effect of education on earnings. Handbook of labor economics, vol 3, pp 1801–1863

Cesur R, Mocan N (2014) Does secular education impact religiosity, electoral participation, and the propensity to vote for Islamic parties? Evidence from an education reform in a Muslim country. Working Paper no. 19769. National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge

Cesur R, Dursun B, Mocan N (2014) The impact of education health and health behavior in a middle income, low education country. Working Paper no. 20764. National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge

Devereux PJ, Hart RA (2009) Forced to be rich? Returns to compulsory schooling in Britain. Working Paper no. 2009/40. University College Dublin

Dictionary of Occupational Titles (DOT) Revised Fourth Edition (1991) United States employment service, and the North Carolina occupational analysis field center. Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research, Ann Arbor. https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR06100.v1

Dulger I (2004) Case study on Turkey rapid coverage for compulsory education program. Paper presented at the Conference on Scaling up Poverty Reduction, Shanghai, China

Dursun B, Cesur R (2016) Transforming lives: the impact of compulsory schooling on hope and happiness. J Popul Econ 29(3):911–956

Dursun B, Cesur R, Kelly IR (2017) The value of mandating maternal education in a developing country. Louisiana State University Working Paper

Erten B, Keskin P (2016) For better or for worse? Education and the prevalence of domestic violence in Turkey. Am Econ J Appl Econ Forthcoming

Grenet J (2013) Is it enough to increase compulsory education to raise earnings? Evidence from French and British compulsory schooling laws. Scand J Econ 115(1):176–210

Gulesci S, Meyersson E (2014) ‘For the love of the republic’ education, secularism and empowerment in Turkey. Working Paper, http://goo.gl/Vncpq

Harmon C, Walker I (1995) Estimates of the economic return to schooling for the United Kingdom. Am Econ Rev 85(5):1278–1286

Imbens GW, Angrist JD (1994) Identification and estimation of local average treatment effects. Econometrica 62(2):467–475

Kırdar MG, Koç İ, Tayfur MD (2016) The effect of compulsory schooling laws on teenage marriage and births in Turkey. Working Paper no 72119. MPRA

Lochner L (2011) Non-production benefits of education: crime, health, and good citizenship. Working Paper no. 16722. National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge

Mocan L (2014) The impact of education on wages: analysis of an education reform in Turkey. Unpublished Working Paper

O’Brien RM (2000) Age period cohort characteristics models. Soc Sci Res 29:123–139

Oreopoulos P (2006a) Estimating average and local average treatment effects of education when compulsory schooling laws really matter. Am Econ Rev 96(1):152–175

Oreopoulos P (2006b) The compelling effects of compulsory schooling: evidence from Canada. Can J Econ 39(1):22–52

Pischke JS, von Wachter T (2008) Zero returns to compulsory schooling in germany: evidence and interpretation. Rev Econ Stat 90(3):592–598

Schultz TP (2002) Why governments should invest more to educate girls. World Dev 30(2):207–225

Stephens M Jr, Yang D-Y (2012) Schooling laws, school quality, and the returns to schooling. Working Paper. University of Michigan

Tansel A (2002) Determinants of school attainment of boys and girls in Turkey: individual, household, and community factors. Econ Educ Rev 21(5):455–470

Tsai W-J, Liu J-T, Chou S-Y, Thornton R (2009) Does educational expansion encourage female workforce participation? A study of the 1968 reform in Taiwan. Econ Educ Rev 28(6):750–758

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank to Sarah Turner, Leora Friedberg, and John Pepper. I also thank seminar participants at the University of Virginia and Southern Economic Association Conference. I am grateful to the editor and two anonymous referees for very useful suggestions and careful reading. I am also grateful to the University of Virginia’s Bankard Fund for financial support and the staff in the Labor Force Statistics Department of Turkish Statistical Institute for providing the supplementary data for Household Labor Force Survey.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

I have no potential conflict of interest that relate to the research described in this paper. Also the views expressed here are my own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Tables

Appendix 2: Data

I use Household Labor Force Survey micro data releases from 2004 to 2011. After merging the original data sets with the single age data and year of birth data, I have the following numbers of observations in each year respectively: 472823, 490,008, 497,132, 481,600, 481,149, 503,329, 522,171, and 517,076 (3,965,288 observations in total). After appending data from 8 years, I drop those who are younger than 20 or older than 29. This leaves me with 600,000 observations. Then I drop observations with inconsistent age and year of birth information (I drop if year of birth is less than (survey year-age-one) or year of birth is greater than (survey year-age)). This leaves me with 599,485 observations. 25,477 (4%) observations among the remaining ones do not have year of birth information, and I drop them as well. Thus I am left with 574,008 observations aged 20–29 from survey years 2004–2011.

The regressions that investigate the effect of the reform on educational attainment use this sample. The sample of non-college bound individuals excludes those who attended college or had graduated from college when surveyed. When I estimate the wage returns to schooling, I drop individuals with monthly wages less than 100 Turkish Liras or more than 4000 Turkish Liras. This corresponds to less than 1 percent of total wage earners with wage information. As I mentioned in fourth section, only 5% of the salary workers have missing wage information.

Key Variables

Schooling

The survey does not provide the exact years of education. Instead it provides the information on the highest completed degree. Therefore I categorize individuals into four: Less than middle school, Middle School Graduates, High School Graduates and College Graduates. In the HLF micro data, those who are in categories 0, 1, 2 are considered in “Less than Middle School” category. Although this category may technically involve who do not have any education at all, the share of this group should be ignorable. Vocational middle school and general middle school are considered in the same category in the survey. I follow the survey design and call them Middle School Graduates. Similarly, vocational and general high school graduates are grouped as High School Graduates. Finally, those who have 2-year college degree or a higher degree are grouped as College Graduates.

The completed years of education is calculated through assignment of usual years of education to each degree. I assign 5 years of education to those who have less than middle school degree, 8 years to those with middle school degree, 11 years to those with high school degree and 15 years to the college graduates.

Age and Year of Birth

As mentioned in the text, I obtained additional data on single age and year of birth of individuals from the Turkish Statistical Institute. I observe the age and year of birth information of 574,008 individuals aged 20–29 from survey years 2004–2011.

Employment Status

The surveys from 2004 to 2008 categorize employment status into five: regular, casual, employer, self-employed and unpaid family worker, whereas surveys 2009–2011 combine the first two into the same category of regular or casual workers. To be consistent, I combine the first two into the same category in the early surveys as well. The category of regular or casual workers is used as the sample of salary workers.

Status of Workplace

Only in the 2009–2011 releases I observe the status of workplace. There are three categories: private, public and other. While investigating the effect of the reform on sectors, the binary indicator for public sector takes the value one for those who are in the second category, and zero for those in the first and the third category.

Type of Residence

The HLS considers the settlements with population of 20,000 and less as rural, and settlements with bigger population as urban. I follow this categorization in my analysis.

Marital Status

I categorize “single that is never married” and “living together without getting married” into the category of “single”, and categorize “married”, “married but not living together”, “divorced” and “widowed” into the category of “ever-married”. So I generate a binary indicator for being ever-married.

Computing DOT Task Means for ISCO-88 Categories

Each DOT category has an assigned number for the task requirement of the occupation in relation to data, people and things. My ultimate target is to obtain assessments of these requirements for ISCO occupation categories in the HLF survey. I start by matching more than 12,000 thousand DOT occupation categories to around 800 SOC-2000 occupation categories. Then I calculate the simple average of three assigned values for each SOC category so that I obtain the task requirement of around 800 SOC occupations regarding data, people and things. Then I match SOC occupation categories to 26 ISCO-88 categories in my survey data, and calculate the simple average of the task values once more. As a result, I obtain three values for each ISCO-88 occupation category regarding the task requirements in relation to data, people and things. Occupation categories that require more complicated tasks have lower values, and those that require less complicated tasks have higher values.

Appendix 3: Theory

Card (1999) assumes that individuals maximize the following utility function by choosing the optimal level of schooling S,

where y (S) denotes the average level of earnings an individual with schooling level S receives, and h(S) is a convex function representing the individual cost of schooling such as forgone earnings, tuition, fees and psychological costs. Including heterogeneity in costs and benefits of schooling yields heterogeneity in optimal schooling levels. Following Card (1999), let the marginal costs and benefits of schooling be characterized by

where bi and ri are random variables with means \( \overline{b} \) and \( \overline{r} \), \( {b}_i=\overline{b}+{\varphi}_i \), \( {r}_i=\overline{r}+{\eta}_i \) where bi corresponds to abilities, ri corresponds to psychological and monetary costs of schooling. k1 and k2 are non-negative constants, representing the concavity of the earning function and convexity of the cost function respectively. The optimal schooling level that solves the problem is

where k = k1 + k2. This shows how individual schooling decisions depend on individual returns and costs and why we expect different returns to schooling at different schooling levels.

In this framework with heterogeneous returns, Card shows that the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) estimate of the effect of schooling on log wages is different from the average effect because individuals with higher returns acquire more schooling. Moreover, because compulsory schooling laws affect some subgroups more than others, IV estimates do not provide an average return.

If there is variable treatment intensity and treatment effect heterogeneity, then the IV estimate can be interpreted as a weighted average of causal responses to a unit change in treatment (Angrist and Imbens 1995). Suppose that the population can be categorized into groups of individuals with common values for ability and taste terms, and the policy intervention leads to a change ΔSg in the mean schooling of group g, and βg denotes the marginal return to schooling for group g in the absence of intervention. Then, following Card’s notation, the IV estimator of the return to schooling has the probability limit

where expectations are taken with respect to the probability distribution of the population across cells. The IV estimator is consistent with the average marginal returns to schooling if there are identical marginal returns across subgroups (\( {\beta}_g=\overline{\beta}\Big) \) or change in schooling is homogenous across subgroups (Card 1999). Within this framework, my estimates revealing the LATE for people induced to attain more schooling after the reform.

Remember, before the reform, the average schooling level among women was significantly lower than among men: 55% of women aged 20–29 and 35% of men aged 20–29 did not have a middle school degree before the reform. Since the ratio of women with less than middle school degree was higher than men in the first place, and since the social and economic barriers were more prominent among women, the compulsory schooling reform that mandates 8 years of schooling is expected to lead to bigger changes in schooling in the sample of women. Moreover, assuming that individuals who have higher cost of schooling also have lower returns to schooling, the average returns to schooling among women who did not have a middle school degree and are enforced to finish eighth grade is higher than those among men. Therefore, an estimation that uses the compulsory schooling reform as an instrumental variable is expected to lead to higher estimated effects among women than among men.

To clarify the case, I propose the following example which models the reform as a complete enforcement. There are four subgroups of individuals with common cost and benefit terms ( bg, ηg) within each subgroup, and log earnings are linear in schooling, i.e. k1 = 0. Let σbη < 0, and b1 < b2 < b3 < b4 and η1 > η2 > η3 > η4 , so those with higher marginal costs of schooling also have lower marginal returns to schooling. Men and women from the same group g have the same characteristics except for the mean marginal cost, \( {\overline{r}}_w>{\overline{r}}_m. \)

Using Eq. (5), the optimal schooling level would be higher in the sample of men as \( {\overline{\ r}}_w>{\overline{r}}_m \). For simplicity, suppose the subgroups of women choose 1, 2, 3, and 4 units of schooling respectively, and the subgroups of men choose 2, 3, 4, and 5 units of schooling. Note that women who have 1 unit of schooling have the same innate characteristics except for \( \overline{r} \) as men who have 2 units of schooling. Now, the compulsory schooling reform makes it mandatory to finish at least 3 units of schooling. The IV estimate will reflect the marginal returns of the first and second group in the sample of women, but the marginal returns of the first group in the sample of men. By assumption b1 < b2, so the LATE in the sample of women will be bigger than the LATE in the sample of men.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Torun, H. Compulsory Schooling and Early Labor Market Outcomes in a Middle-Income Country. J Labor Res 39, 277–305 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-018-9264-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-018-9264-0