Abstract

This article is the first study to present an econometric evaluation of wage discrimination based on sexual orientation in the French labor market. Having identified same-sex couples using the French Employment Survey, we estimate the wage gap related to sexual orientation in the private and public sectors, in order to analyze whether or not lesbians and gays suffer a wage penalty. The results obtained show the existence of a wage penalty for homosexual male workers, as compared with their heterosexual counterparts, in both the private and public sectors; the magnitude of this discrimination varies from about −6.5 % in the private sector, to −5.5 % in the public sector. In the private sector, the wage penalty suffered by gay employees is higher for skilled workers than for the unskilled, and—in both sectors—the wage penalty is higher for older workers than for younger ones. As with many other countries, we do not find any evidence of the existence of a wage discrimination against lesbians.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Badgett (2006) for a survey of this literature.

If a significant proportion of heterosexual employees is homophobic, hiring homosexual workers can lead to a decrease in individual productivity of both homosexuals (harassment, depression, lack of motivation, etc.) and heterosexuals (lack of concentration, lost time, etc.).

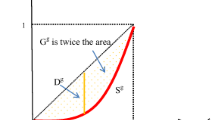

Oaxaca (1973), in his seminal study on gender wage discrimination, shows that the share of the gender wage gap due to discrimination, decreases from 77 % to 58 % when controlling for industry and occupation.

If the probability of accessing executive positions is lower for homosexuals than for heterosexuals with identical characteristics, but once gays and lesbians become executives they are paid the same, (i) the proportion of gay or lesbian employees among executives will be low (gay glass ceiling) and thus the average wage will be lower for homosexual employees than for heterosexual ones, but (ii) a wage discrimination based on sexual orientation will appear, only if the variable “Executive position vs. non-executive position” is not used as a control variable in the wage equation.

This point is also emphasized by Carpenter (2004)

This measurement error can however be reduced by filtering populations of cohabitants on the basis of various criteria: age (to eliminate juvenile cohabitation), family links, income (economic cohabitation), nationality (to exclude migrant workers), etc. Several articles show, that identifying homosexual populations via a cohabitation criterion is precise and efficient (see Black et al. 2000; Carpenter 2004) and that the bias associated with this method is less than 0.4 %.

See Arabsheibani et al. (2004, 2005, 2007), Black et al. (2003), Elmslie and tebaldi (2007), Ahmed and Hammarstedt (2009), Carpenter (2004, 2007a, 2008b) and, for France, Digoix et al. (2004), Toulemon et al. (2005). On average, in these various studies, about 27 % of heterosexual men and women have college education, as compared with 43 % of gays and over 48 % of lesbians

Same references as the previous footnote

On average, in the various studies, about 40 % of heterosexual men and women have children as compared with 4.5 % of gays and 18 % of lesbians (same references that supra; see also Frank 2006)

Especially the correction, or not, of the selection bias by estimating first a probit model of participation (Heckman two-step estimation).

Articles 225-1, 225-2, 132-77, 222-18-1. English translation of the Code available at: http://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/content/download/1957/13715/version/4/file/Code_33.pdf

IPSOS survey conducted in 2004 for the newspaper Têtu, on a national sample of 1,002 persons, representative of the French population over 15 years of age.

European Commission (2008), Discrimination in the European Union: 2008, Eurobarometer Special survey n°296.

2009 Report on Homophobia, Association SOS Homophobia ed.

CSA Institute, poll n° 0900383: Perception of discriminations in the workplace: viewpoints of private sector employees and of public servants, conducted in March 2009 on national representative samples of private and public sector employees.

The threshold value of 1,000€ has been indexed in accordance with the evolution of the average wage. A lump-sum income of 300 €/month, corresponding to a reservation income, has been attributed to inactive members of the couples. Similarly, a lump-sum income of 1,000€/month has been attributed to independent workers. This value, equal to the first quartile of the distribution of independent workers (Rouault 2001), was selected to be sure that all potential economic cohabitation has been eliminated.

Throughout this article, we use the terms “male homosexuals” or gays—and “female homosexuals” or lesbians—to denote the members of our samples of same-sex couples.

Survey on Sexual Behavior in France (ACSF), conducted in 1992 (cf. Les comportements sexuels en France, Spira A., Bajos N. and the ACSF team, La Documentation Française, Paris, 1993).

In an imperfect information framework such a difference could be explained by a strategic behavior of gay employees, to prevent their employers from accumulating over time a sufficient amount of information, leading to the revelation of their sexual orientation.

See for example Antecol and Steinberger (2009), for an econometric study of the central role played by sexual orientation on labor supply in the US.

The wage w i is a net monthly salary including all monetary compensation.

Note that the cause of the selection bias is not the consequence of having a non-random sample, but arises merely because individuals whose observable characteristics are unfavorable have a large error term in the selection equation

The residual variance of the earning equation also depends on the Mills ratio and, therefore, on individual characteristics.

The addition of these new variables can be viewed as the introduction of specific constraints necessary for identification.

Sexual orientation is not introduced in the selection equation. Nevertheless, to be cautious, we decided to re-estimate the model with a selection equation including sexual orientation as an explanatory variable. All the estimated parameters of the wage equation and, in particular, the estimates of the wage discrimination remained the same. The results are available upon request.

The definition of the private sector used here includes the large national public companies.

As we use pool data on the period 1996–2007, we include in all regressions time dummies variables to control for structural breaks other the estimation period.

With the semi-logarithmic specification we used, the net impact on wage of the sexual orientation is given by eβi−1 where β i is the estimated coefficient associated with the explanatory variable Gay or Lesbian.

As in the US, the higher level of wages earned by lesbians, compared to heterosexual females, is mainly due to a higher level of investment in human capital, particularly in education (see for example Antecol et al. (2007)).

For example, for high-skill jobs, the explanatory variable “Number of children” is statistically significant and plays negatively, while the variable “Number of children × Public sector” is statistically significant and plays positively. This means that the return associated to the number of children in the private sector is equal to e −0.004−1 = −0.4 % while it is equal to e −0.004+0.015−1 = +1.11 % in the public sector.

We focus in this article on wage discrimination only but of course discrimination in low wage jobs can take many other forms than wage differences: barriers to entry for gay men, characteristics that discourage gay men from applying etc.

This explains the lower job stability of gay employees as compared to their heterosexual counterparts (see Table 1).

References

Ahmed AM, Hammarstedt M (2009) Sexual orientation and earnings: a register data based approach to identify homosexuals. J Popul Econ, July

Allegretto SA, Arthur M (2001) An empirical analysis of homosexual/heterosexual male earnings differentials: unmarried and unequal? Ind Labor Relat Rev 54(3), April

Antecol H, Steinberger M (2009) Female labor supply differences by sexual orientation: a semi-parametric decomposition approach. IZA Discussion Paper n°4029, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA), February

Antecol H, Jong A, Steinberger M (2007) The sexual orientation wage gap: the role of occupational sorting, human capital, and discrimination. IZA Discussion Paper n°2945, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA), July

Arabsheibani GR, Marin A, Wadsworth J (2007) Variations in gay pay in the USA and the UK. In: Badgett L, Frank J (eds) Sexual orientation discrimination: an international perspective. Routledge, London

Arabsheibani GR, Marin A, Wadsworth J (2002) Gays’ pay in the UK, n°8, Royal Economic Society Annual Conference 2002 from Royal Economic Society

Arabsheibani GR, Marin A, Wadsworth J (2004) In the pink: homosexual/heterosexual wage differentials in the UK. Int J Manpow 25(3–4):343–354

Arabsheibani GR, Marin A, Wadsworth J (2005) Gays’ pay in the UK. Economica 72:333–347

Arrow K (1973) The theory of discrimination. In: Ashenfelter O, Rees A (eds) Discrimination in labor markets. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Badgett L (1995) The wage effects of sexual orientation discrimination. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 48(4):726–739

Badgett L (2001) Money, myths, and change: the economic live of lesbians and gay men. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Badgett L (2006) Discrimination based on sexual orientation: a review of the literature in economics and beyond. In: Rodgers WM III (ed) Handbook on the economics of discrimination. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham

Badgett L, Lau H, Sears B, Ho D (2007) Bias in the workplace: consistent evidence of sexual orientation and gender identity discrimination. University of California Los Angeles, UCLA, The Williams Institute, June

Becker GS (1957) The economics of discrimination. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Becker GS (1965) A theory of the allocation of time. Economic Journal 75(299):493–517

Becker GS (1981) A treatise on the family. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Berg N, Lien D (2002) Measuring the effect of sexual orientation on Income: evidence of discrimination? Contemporary Economic Policy 20(4):394–414

Berill KT (1992) Anti-gay violence and victimization in the United States: an overview. In: Herek GM, Berill KT (eds) Hate crimes: confronting violence against lesbians and gay men. Sage, Newbury Park

Berson C (2009) Private vs. public sector: discrimination against second-generation immigrants in France, Working Paper of the Sorbonne Center for Economics, n°2009-59, University Paris 1 Pantheon-Sorbonne, September

Black D, Makar H, Sanders S, Taylor L (2003) The earnings effects of sexual orientation. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 56(3):449–469

Black D, Gates G, Sanders S, Taylor L (2000) Demographics of the gay and lesbian population in the United States: evidence from available systematic data sources. Demography 37(2):139–154

Blandford JM (1999) Sexual orientation’s role in the determination of earnings and occupational outcomes: theory and econometric evidence, Dissertation

Blandford JM (2000) Evidence on the role of sexual orientation in the determination of earnings outcomes. Working Paper Harris Graduate School of Public Policies Studies, University of Chicago

Blandford JM (2003) The nexus of sexual orientation and gender in the determination of earnings. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 56(4):622–42

Blinder AS (1973) Wage discrimination: reduced form and structural estimates. The Journal of Human Resources 8:436–455

Calandrino M (1999) Sexual orientation discrimination on the UK labor market. Working Paper St. Antony’s College, University of Oxford

Carpenter CS (2004) New evidence on gay and lesbian household incomes. Contemporary Economic Policy 22(1):78–94

Carpenter CS (2005a) Self-reported sexual orientation and earnings: evidence from California. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 58(2):258–273

Carpenter CS (2005b) Heterosexual signalling and the marriage premium. Unpublished paper

Carpenter CS (2007a) Revisiting the income penalty for behaviorally gay men: evidence from NHANES III. Labour Economics 14:25–34

Carpenter CS (2007b) Do straight men “come out” at work too? The heterosexual male marriage premium and discrimination against gay men. In: Badgett L, Frank J (eds) Sexual orientation discrimination: an international perspective. Routledge, New York, pp 76–92

Carpenter CS (2008a) Sexual orientation, work, and income in Canada. Canadian Journal of Economics 41(4):1239–1261

Carpenter CS (2008a) Sexual orientation, income, and non-pecuniary economic outcomes: new evidence from young lesbians in Australia. Review of Economics of the Household, Springer Netherlands ed., Vol. 6, n°4, December, pp 391–408

Clain HS, Leppel K (2001) An investigation into sexual orientation discrimination as an explanation for wage differences. Appl Econ 33(1):37–47

Digoix M, Festy P, Garnier B (2004) What if same-sex couples exist in France after all? In: Digoix M, Festy P (eds) “Same-sex couples, same-sex partnerships & homosexual marriages: a focus on cross-national differentials”., Ined, Working Paper n°124

Elmslie B, Tebaldi E (2007) Sexual orientation and labor market discrimination. Journal of Labor Research 28(3):436–53

Frank J (2006) Gay glass ceilings. Economica 73:485–508

Frank J (2007) Is the male marriage premium evidence of discrimination against gay men? In: Badgett L, Frank J (eds) Sexual orientation discrimination: an international perspective. Routledge Press, New York

Heckman J (1976) The common structure of statistical models of truncation, sample selection and limited dependent variables and a simple estimator of such models. Annals of Economic and Social Measurement 5:475–492

Heckman J (1979) Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica 47(1):153–161

Heineck G (2009) Sexual orientation and earnings: evidence from the ISSP. Applied Economics Letters 16(13):1351–54

Hoffnar E, Greene M (1996) Gender discrimination in the public and private sectors: a sample selectivity approach. J Socio-Econ, Elsevier 25(1):105–114

Irwin J (1999) The pink ceiling is too low: workplace experiences of lesbians, gay men and transgender people. Australian Centre for Lesbian and Gay Research, New South Wales: Gay and Lesbian Rights Lobby

Kite ME, Whitley BE (1996) Sex differences in attitudes toward homosexual persons, behaviors, and civil rights: a meta-analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 22:336–353

Klawitter M (1997) The effects of sexual orientation on the determinants of earnings for women. Working Paper, University of Washington

Klawitter M (1998) The determinants of earnings for women in same-sex and different-sex couples. Working Paper, University of Washington

Klawitter M, Flatt V (1998) The effects of state and local antidiscrimination policies on earnings for gays and lesbians. J Policy Anal Manag 17(4):658–686

Meurs D, Ponthieux S (2000) Une mesure de la discrimination dans l’écart de salaire entre hommes et femmes. Economie et Statistiques, n° 337–338

Meurs D, Ponthieux S (2006) L’écart des salaires entre les femmes et les hommes peut-il encore baisser? Economie et Statistiques, n° 398–399

Oaxaca RL (1973) Male–female wage differentials in urban labour markets. Int Econ Rev 14:693–709

Oaxaca RL, Ransom MR (1994) On discrimination and the decomposition of wage differentials. Journal of Econometrics 61:5–21

Pew Research Center for the People and the Press (PRCPP) (2002) What the World Thinks in 2002. Topline Results

Phelps ES (1972) The statistical theory of racism and sexism. American Economic Review 62:659–661

Plug E, Berkhout P (2004) Effects of sexual preferences on earnings in the Netherlands. Journal of Population Economics 17:117–131

Plug E, Berkhout P (2008) Sexual orientation, disclosure and earnings,. IZA Discussion Paper, n°3290

Rouault D (2001) Les revenus des indépendants et dirigeants: la valorisation du bagage personnel. Economie et Prévision 348:35–59

Toulemon L, Vitrac J, Cassan F (2005) Le difficile comptage des couples homosexuels d’après l’enquête EHF. In «Histoires de familles, histoires familiales », sous la direction de Cécile Lefèvre et Alexandra Filhon, Ined, les Cahiers de l’Ined, n° 156, partie IX.32, pp 589–602

Zweimuller J, Winter-Ebmer R (1993) Gender wage differentials in private and public sector jobs. J Popul Econ, Springer 7(3):271–85

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Annex: Variables Used in the Selection and Wage Equations

Annex: Variables Used in the Selection and Wage Equations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Laurent, T., Mihoubi, F. Sexual Orientation and Wage Discrimination in France: The Hidden Side of the Rainbow. J Labor Res 33, 487–527 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-012-9145-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-012-9145-x