Abstract

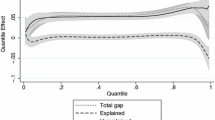

This paper provides insight into the wage gap between lesbians and heterosexual women. Using data from the 2000 Decennial Census, we find a lesbian premium that equals approximately 10% for women without a bachelor’s degree, and is nearly non-existent for women with higher levels of education. These findings are consistent with proposition that the gap between lesbians’ and heterosexual women’s commitment to the labor market narrows at higher levels of education. We also find that controls for industry and occupation exert only a small effect on the gap between lesbian and heterosexual women’s wages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Jepsen’s analysis concentrates, primarily, on the magnitude of the coefficient associated with a lesbian indicator variable; she does not examine how the premium varies over workers’ careers and at different levels of education.

Concentrating on full-time workers avoids potential biases resulting from differing wage or compensation structures between full-time and part-time workers.

The analyses presented in this paper were also performed between lesbians and samples of the three relationship categories (married, single and cohabiting) of heterosexual women separately. With minor differences among the groups, the results are similar to those reported. For the sake of brevity, we do not report these results, but they are available upon request.

The specification includes a quadratic term for potential experience, as well as the associated interactions with R. Vector X includes four indicator variables for race, three indicators for region of residency, an indicator for residing in a metropolitan area, and an indicator for work-limiting disability. Following Waldfogel (1998) and others, we do not include occupational or industry variables in the regression analysis because these choices are likely correlated with unobservable investments in human capital, commitment to market work, market discrimination, and other important unobservable factors that may differ systematically across the groups examined in the study. In regressions not reported, where occupational and industry variables are included, the qualitative nature of the results discussed below do not change.

To the extent that heterosexual females have higher occurrences of temporary labor-market separation than lesbians and males, the gap between actual and potential experience will be systematically larger for them. If this is the case, potential experience systematically overestimates heterosexual females’ actual experience, depressing their estimated return to experience. Additionally, because traditional gender roles affect heterosexual women’s investment in human capital, career decisions, and labor market commitment, they are predicted to have flatter profiles even in the absence of measurement error. In fact, Waldfogel (1998) and Wellington (1993), who use data that contain information on actual experience, find lower returns for women.

Standard Chow tests allow us to reject the null hypothesis that the coefficients for the two sub-samples are equal. The actual F value with 17 and 98,649 degrees of freedom is 66.8.

Neumark (1988) and Oaxaca and Ransom (1994, 1998) propose and test a generalized form of the nondiscriminatory wage structure by pooling the two samples and using the cross-product matrices of the explanatory variables as weights for the parameters of separately estimated wage structures of the two groups. The approach eliminates the assumption that the nondiscriminatory wage structure equals a convex, linear combination of separately estimated wage structures of the two groups.

The percentage differential equals e(log points)−1, which equals e(0.22)−1 = 0.246. Unless indicated otherwise, all estimates are statistically different from zero at standard levels.

References

Badgett MV (1995) The wage effects of sexual orientation discrimination. Ind Labor Relat Rev 48:726–739, July

Berg N, Lien D (2002) Measuring the effect of sexual orientation on income: evidence of discrimination? Contemp Econ Policy 20:394–414, October

Black DA, Gates G, Sanders S, Taylor L (2000) Demographics of gay and lesbian population in the United States: evidence from available systematic data sources. Demography 37:139–154, May

Black DA, Maker HR, Sanders SG, Taylor LJ (2003) The earnings effects of sexual orientation. Ind Labor Relat Rev 56:449–469, April

Blandford JM (2003) The nexus of sexual orientation and gender in the determination of earnings. Ind Labor Rel Rev 56:622–642, July

Blau FD, Kahn LM (2004) The US gender pay gap in the 1990s: slowing convergence. Working Paper no. 10853. NBER, Cambridge, MA

Blau FD, Ferber MA, Winkler AE (2006) The economics of women, men, and work. Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ

Carpenter CS (2005) Self-reported sexual orientation and earnings: evidence from California. Ind Labor Relat Rev 58:258–273, January

Clain SH, Leppel K (2001) An investigation into sexual orientation discrimination as an explanation for wage differences. Appl Econ 33:37–47, January 2001

Elmslie B, Tebaldi E (2007) Sexual orientation and labor market discrimination. J Labor Res (in press)

Hersch J, Stratton LS (1994) Housework, wages, and division of housework time for employed spouses. In: The American economic review: papers and proceedings of the hundred and sixth annual meeting. American Economics Association, Nashville, TN, 1994:120–124

Jepsen LK (2007) Comparing the earnings of cohabiting lesbians, cohabiting heterosexual women, and married women: evidence from the 2000 census. Indust Relat (in press)

Klawitter MM, Flatt V (1998) The effects of state and local antidiscrimination policies on earnings for gays and lesbians. J Policy Anal Manage 17(4):658–686

Neumark D (1988) Employer’s discriminatory behavior and the estimation of wage discrimination. J Hum Resour 23:279–295, Summer

Oaxaca RL, Ransom MR (1994) On discrimination and the decomposition of wage differentials. J Econom 61:5–21

Oaxaca RL, Ransom MR (1998) Calculation of approximate variances for wage decomposition differential. J Econ Social Meas 24:55–61

Tebaldi E, Elmslie B (2006) Sexual orientation and labor supply. Appl Econ 38:549–562

US Census Bureau (2002) Technical note on same-sex unmarried partner data from the 1990 and 2000 Censuses. Available from: <http://www.census.gov/population/www/cen2000/samesex.html>, July 31, 2002

Waldfogel J (1998) The family gap for women in the United States and Britain: can maternity leave make a difference? J Labor Econ 16:505–545, July

Wellington AJ (1993) Changes in the male–female wage gap, 1976–85. J Hum Resour 28:383–411

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Stephen Miller, Paul Thistle, Lori Temple and an anonymous reviewer for their comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Daneshvary, N., Waddoups, C.J. & Wimmer, B.S. Educational Attainment and the Lesbian Wage Premium. J Labor Res 29, 365–379 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-007-9024-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-007-9024-z