Abstract

This article contributes to our existing knowledge through a crime script analysis of contract killings, based on six extensively analyzed police investigations in the Netherlands. Starting from a universal crime script, a more specific crime script for contract killings is elaborated. To provide a clear picture of the whole process, the description of the scenes focuses on requirements, facilitators, modi operandi, and preparatory actions. A comparison of liquidation investigations is made through a crime script analysis, which results in three types of requirements: vehicles, automatic weapons, and technical equipment, including PGP-telephones and beacons. In addition, spy shops turn out to play a major role in liquidations as facilitators. Due to a lack of licensing and regulations, the owners of spy shops can decide to a large extent on their own procedures. This leads to the possibility of buying and selling equipment anonymously and with large amounts of cash, which facilitates the preparation of liquidations and crime in general. Hitmen are the second type of important facilitators. The analysis reveals that all liquidation investigations contain indications of a principal to whom account has to be held. Two investigations clearly demonstrate financial rewards for contract killings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Contract killings shock society and create abundant media attention, yet sound empirical research into this phenomenon is extremely scarce. Most academic research focuses on motives and backgrounds of conflicts or the personal backgrounds of hitmen and victims (e.g. Black and Cravens 2001; Van de Port 2001; Mouzos and Venditto 2003; Van de Bunt and Kleemans 2007; Cameron 2014; MacIntyre et al. 2014; Van Gestel and Verhoeven 2017; Van Gestel and Kouwenberg 2019). This article aims to contribute to our existing knowledge through a crime script analysis of contract killings, based on six extensively analyzed police investigations in the Netherlands. The general idea behind crime script analysis (Cornish 1994) is that a very detailed analysis of criminal activities creates a deeper understanding of the various ways in which criminal activities can be carried out and the essential logistical bottlenecks and facilitators for the successful commission of crimes. This detailed analysis may also create valuable information for situational crime prevention measures (Leclerc 2013). A systematic review by Dehghanniri and Borrion (2019) shows that the use of crime script analysis is increasing and focuses on various types of crime; however, crime script analyses of contract killings are largely missing in the (English language) literature. One notable exception is the study by Black and Cravens (2001), which is not mentioned in the systematic review.

This article starts with a brief review of the literature on contract killings and crime script analysis. Next, we describe how crime script analysis is used in this research project, based on a detailed analysis of six police investigations in the Netherlands. The next section presents the results of the crime script analysis with a specific focus on both requirements and facilitators (playing an important role in the process). In the final section, the main conclusions are summarized and discussed.

Contract killings and facilitators

Most of the academic literature on contract killings focuses on motives and backgrounds of conflicts and the personal backgrounds of hitmen and victims, although definitions of what exactly constitutes a ‘contract killing’ vary (e.g. Kleemans et al. 1998; Black and Cravens 2001; Van de Port 2001; Mouzos and Venditto 2003; Van de Bunt and Kleemans 2007; Cameron 2014; MacIntyre et al. 2014; Van Gestel and Verhoeven 2017; Van Gestel and Kouwenberg 2019). Some studies focus on contract killings in the criminal environment or organized crime, but other studies use a much wider definition of a contract killing. The early study by Black and Cravens (2001) uses crime script analysis to investigate the process of contract killings. Three stages of the process are distinguished. First, there is a need for a principal viewing a contract killing as the sole solution to a problem. Second, a subsequent stage involves searching for a hitman. The analysis shows that principals recruit hitmen either through involving people in their direct social environment or through approaching a professional. The moment concrete agreements are made regarding modus operandi and rewards can be viewed as the third stage of the process. Black and Cravens (2001), however, focus on contract killings in general and not particularly on contract killings in the criminal environment or organized crime. Therefore, it is unclear whether their results also apply to contract killings in the criminal environment. Nevertheless, the analysis does identify some basic elements: a principal and a hitman getting a (financial) reward for carrying out the job.

When focusing on contract killings in the criminal environment, one of the problems of definitions is that some of the elements of a killing, such as modus operandi, may be clear at some point, but other elements, such as the criminal background of offenders and victims or motives of the conflict, can only be clarified after considerable time, if at all. A main problem of many definitions is that the motive of the offender plays an important role, but is often unknown. Van de Port (2001) delves deeper into this problem and argues that contract killings are not a uniform phenomenon, but get the label ‘contract killing’ through interpretations of a violent death. According to Van de Port (2001), therefore, the motive should be leading and not the way in which a murder is carried out (Van de Port 2001). In practice, however, the modus operandi and the circumstances of the act often share similar characteristics, such as public or semi-public settings, how the murder is carried out, and how proof is destructed afterwards. The cases that have been analyzed in depth for this article also show strong similarities in requirements, preparations, and the ways in which proof is destructed afterwards (see also the empirical results section).

When carrying out criminal activities, offenders face several bottlenecks. Facilitators may help overcome these bottlenecks. Clarke (1997) first defined facilitators in terms of essential goods for specific forms of crime, such as weapons, but also alcohol or drugs (as they lower the threshold for criminal behavior). Only later on, as Von Lampe (2011) explains, the concept of facilitators was broadened to persons.

Facilitators, therefore, may not only refer to goods, but also to persons used by criminal groups or networks for specific services. Facilitators may carry out activities which offenders are unable to carry out themselves (as they don’t have the capacities) or which offenders do not want to carry out themselves, as they are too risky (Kleemans et al. 2002). If we apply this to contract killings, one type of facilitator immediately comes to the fore: the hitman, carrying out an activity which principals cannot or do not want to carry out themselves (because of the risk). A substantial part of the scarce academic literature on contract killings focuses on (the personal backgrounds of) hitmen (e.g. Black and Cravens 2001; Mouzos and Venditto 2003; Cameron 2014; MacIntyre et al. 2014). This article, however, will not focus on hitmen alone, but on the whole process of a contract killing by employing crime script analysis.

Method: crime script analysis

Dehghanniri and Borrion (2019) published a systematic review showing that the use of crime script analysis is increasing. Cornish (1994) was the first to transpose the use of scripts, originally used in psychology, to the study of crime. Criminal events take place at a certain place and time, but are only one of the many acts happening during the whole process leading to this event. A criminal event is the result of a series of decisions and actions and subsequently leads to a new series of decisions and actions. A crime script includes all actions before, during, and in the aftermath of a criminal event and a crime script analysis aims to describe this whole process. Crime scripts can focus on different types of criminal activities (see Dehghanniri and Borrion 2019) and may vary in level of specificity. The universal crime script is the most general script consisting of a series of sequential scenes of the whole process. It provides a procedural background to analyze data and, as the crime script includes the whole process, it stimulates a researcher to investigate all aspects of this process (Cornish 1994).

Crime scripts focus on crime as a dynamic activity and the content of specific criminal activities. Crimes need specific actions, persons, locations, and objects. Organized crimes, however, are often much more complex, as they require more activities, offenders, locations, and longer preparation periods (see e.g. Bullock et al. 2010; Von Lampe 2011). Nevertheless, crime scripts do still have added value for research into organized crime, as they provide empirical insight into what offenders need to carry out criminal activities. They might indicate which tools are necessary and also illuminate the nature of the criminal activities (Bullock et al. 2010; Hancock and Laycock 2010). The use of crime script analysis has two important – interrelated—advantages. First, it provides a standard model to investigate a crime as systematically and detailed as possible. Second, a crime script can be elaborated later on, when more information becomes available. New information from new cases can be added, resulting in a more detailed crime script (Brayley et al. 2011). This way, a comprehensive overview is produced of the various requirements and modi operandi of a specific crime or criminal activity (Cornish 1994).

A practical consequence is that the detailed knowledge of a crime script analysis makes it possible to discover opportunities for situational crime prevention and interventions. If crucial actors and requirements are known, targeted interventions may frustrate the successful completion of these criminal acts. A possible consequence, however, is that offenders find new ways to overcome these new barriers. Crime scripts may involve specific barriers and various routes to a specific goal; and more routes relate to a more flexible crime script. Detailed knowledge about various routes and various ways in which offenders might adapt makes it possible for the police to intervene at certain points and restrain the flexibility of offenders (Brayley et al. 2011; Leclerc 2013).

Crime script analysis and liquidation investigations

For this article, a universal crime script is used for data analysis, as crime script analysis has not been used in much detail before for the analysis of contract killings. The use of a universal crime script with various fixed scenes has three advantages. First, this way, various criminal investigations can be analyzed and compared relatively easily. Second, various modi operandi can be identified. Third, it makes is easy to recognize potential similarities in actions and requirements within scenes. Next, the scenes of the standardized universal script were used to create a specific crime script for contract killings. This was done before the data-analysis, based on known information of the process of a contract killing. During the data-analysis this script could then be adjusted, if certain scenes were not fully applicable. The process of contract killings was divided into the scenes of the universal script to make it easier to systematically analyze the huge amount of information that is generated in criminal investigations into contract killings. This resulted in eight scenes, nested within the three universal scenes (preparation, execution, and the aftermath of a contract killing). During the data-analysis, information from the investigations was placed within the matching scene. The universal script made in advance turned out to be well applicable to the whole process. The content of the scenes was based on the data-analysis.

To provide a clear picture of the whole process, the description of the scenes focuses on requirements, facilitators, modi operandi, and preparatory actions. The academic literature on contract killings is scarce, so the data analysis resulted in a further elaboration of the crime script. Table 1 shows the analysis scheme used in this research project. The fully elaborated crime script is included at the end of the article.

This way, a crime script analysis was made of the files of six extensive police investigations of the Dutch National Police into contract killings (period: 2013–2015). The selection of criminal investigations was based on the empirical insight the investigations could provide into the process of contract killings. Two investigations involved attempted contract killings, two the preparation of a contract killing, one the organized theft of vehicles, and one arms trade connected to contract killings. Strictly speaking, the last two investigations do not focus on contract killings, but provide insight into the role of facilitators in the process of preparing a contract killing. The reason for selecting these files, therefore, was the amount of information the investigations produced about (a part of) the whole process of a contract killing; a completed or successful contract killing was not necessary. It is important to stress that a deceased victim is not a requirement for getting empirical insight into the process of a contract killing. Often a good information position of the police regarding the preparation of a contract killing – e.g. through wiretapping, bugging, observation, informers, et cetera – results in the prevention of a killing, if possible, either through police interventions or through warning the potential target. This means that investigations into interrupted contract killings may provide as much, or even more information than investigations into completed contract killings. The survival of a target / victim may also result in statements that give extra insight into the process of the contract killing and the reasons why the contract killing failed.

Results – requirements and facilitators

The crime script analysis of six criminal investigations produced various remarkable similarities, particularly regarding requirements and two types of facilitators. First, we discuss requirements for the process of contract killings: stolen vehicles, weapons, and technical equipment. Second, we elaborate upon two types of facilitators: spy shops and professional hitmen.

Requirements

Vehicles

The criminal investigations provide a detailed picture of the type of cars suspects used before and after the contract killings. The analysis shows that all suspects used several stolen vehicles, for the execution of the killing and as a getaway car. Vehicles from the four contract killings investigations and the investigation into organized car theft share a number of similarities: color, car brand, model, and year of construction. All cars had a dark color, mainly black and grey. The group that delivered stolen cars to order focused on dark-colored cars. Sixteen of the 27 stolen cars were dark-colored and three cars were used in three liquidation attempts. In addition to the color, it is striking that the brands of the cars are limited to BMW, Volkswagen, and Audi. This can be explained by the models that have been stolen, namely models with a top speed above 200 km per hour. Speed plays an important role, as is evident from various wiretapped conversations; "do you mean fast things", "do you have anything fast", "is it something fast? Fast torrie?," "is it fast or not?" and "a quick 5 done" are some statements emphasizing the speed of the car. The question of why speed of a car is so important is answered by one of the suspects: “Not to be caught in pursuits. To rob. To kill”. Finally, it appears that the stolen cars all relate to an older year of construction, between 2002 and 2008. This has to do with the fact that Volkswagen and Audi cars built during that period contain security errors. These cars, therefore, are easy to steal through the use of advanced equipment.

In addition to vehicles, the analysis shows that, in the four liquidation investigations, the suspects possess a total of more than 45 automatic weapons (of which 39 in one investigation). The models used are AK-47, also known as the Kalashnikov, and assault rifles produced in Eastern Europe, the CZ VZ.58 and Skorpion machine pistols. The first explanation for the popularity of automatic weapons is the ease with which these weapons can be obtained. Large batches of rejected automatic weapons come from the Eastern Bloc and are easily made workable again. Secondly, automatic weapons provide a degree of certainty when carrying out a contract killing. The caliber of automatic weapons causes great damage to the victim and a large amount of shots per minute can be fired. This combination significantly increases the success rate of a contract killing. Finally, hitmen also use the automatic weapons as a deterrent to the police. Hitmen don't back down from firing at police with automatic weapons while escaping, forcing police to interrupt the chase.

Pretty-Good-Privacy telephones (PGPs)

The analysis also shows that Pretty-Good-Privacy telephones (PGPs) and beacons play an important role in contract killings. In all analyzed investigations, suspects communicated through the use of PGPs which provide the opportunity to send encrypted messages and emails. As only the receiver has the code to decrypt the messages, this facility makes it possible to share sensitive information without notice of the police. The use of PGPs hinders the gathering of proof of criminal activities; in some cases, however, PGPs provide a crucial source of information, when the authorities are able to seize servers and decrypt the messages. Criminal investigations which succeeded in this daunting venture, demonstrate that these (supposedly secret) messages contain a lot of incriminating evidence, literally referring to when victims will be killed, that victims will be “swept” tomorrow or the day after tomorrow, or that “we will sweep him, one way or another.” Good communication between offenders is essential for the organization and execution of a contract killing. PGPs provide a communication tool making it possible to share vital information, shielded from the authorities.

Beacons

Next to PGPs, four liquidation investigations resulted in the discovery of a total of ten beacons. Some of these beacons had not been activated yet and were seized in homes of suspects. In all liquidation investigations, the police found a beacon under the intended victim's car: "we now have something under his < Dutch slang for car > ". Beacons are easy and legal to buy at so-called spy shops and range in price from 1100 to 1500 euros. After activation of the beacon, the location of the intended victim can be easily traced on a tablet, smartphone, or computer by logging into the beacon via a web address. Following and observing a target is difficult and risky, whereas placing a beacon makes is possible to follow a target and cover-up the preparations of a contract killing. Without physical pursuit of the target, suspects still get a picture of the target’s daily routines. This is an advantage because the victims themselves are also active in the criminal environment, which makes them suspicious and attentive to potential signals of pursuit or danger. As a result, the risk of physical observation and pursuit is much higher than when using a beacon. Furthermore, a beacon also provides hitmen more certainty when carrying out a contract killing. When the location of the target can be specifically determined, it becomes easier to kill the victim successfully. Hitmen are better able to anticipate future situations and the environment, which benefits the preparation and actual execution of a contract killing.

In conclusion, the analysis shows that in the process of contract killings use is made in particular of stolen vehicles with high power and older years of construction. In addition, automatic weapons are popular for the execution of the contract killings, because of their positive contribution to the success rate of the offence. Finally, technical equipment appears to play a major role in both preparation and implementation. PGPs allow criminals to communicate safely and plan the crime without fear of any police officers listening in. Beacons help hitmen remotely determine the routines of the intended victim and—at the time of the contract killing – his or her exact location. This significantly increases the success rate of liquidations.

Facilitators

The analysis reveals four types of facilitators that play a role in the crime script: arms dealers, car suppliers, spy shops, and hitmen. The latter two are discussed in more detail, as this research has revealed relatively much information about the role of spy shops and hitmen and relatively less about arms dealers and car suppliers.

Spy shops

The previous section addressed the technical equipment used by suspects during the liquidation process. All this equipment can be purchased legally from spy shops. Previous research into the role of spy shops shows that criminals make use of the services of spy shops when evading the police and the judiciary (Huisman 2011; Bijlenga and Kleemans 2018). In the four analyzed liquidation investigations, the suspects bought beacons and PGP-telephones from spy shops. The analysis shows that two spy shops supplied the equipment to suspects from multiple investigations. Spy shops have a dubious position as they are basically legal companies with a market that largely coincides with the criminal underworld. Unlike private investigation agencies, spy shops have no licensing, no specific regulations, and no trade association. There are no requirements for the ways in which spy shops operate (Huisman 2011). Many of the products sold in a spy shop cannot be considered illegal due to their neutral nature. It is the customers who use the products for legal or illegal practices. In addition, it is difficult to determine when a spy shop consciously facilitates crime. Due to this lack of licensing and regulations, the owners of spy shops can decide to a large extent on their own procedures.

The analysis reveals that spy shops are attractive to criminals for two reasons: anonymity and cash payments. First, it is not mandatory for spy shops to register the identity of customers when purchasing products. "You do not need to identify yourself in the case of a purchase (…). We ask the customer if the receipt should be registered. If this is not desired, we put the name of our company on it," according to a statement of a spy shop owner. Another manager states: "We do not register who buys something and do not require an identification." This means that, at a later date, no link can be established between a person and purchases from a spy shop; in contrast to purchases from online web shops, which do leave traces.

Second, cash payments are accepted for the generally expensive products. Cash payments allow customers to pay large amounts in a discrete way and these transactions are no longer traceable. The fact that large amounts are often charged is demonstrated by the following statements by the manager and the owner of the two spy shops: "We have no limit on cash payments", "I do not think €4400 is a large amount to have in your pocket when you come to us", "with us everything is paid in cash. €4400 is not a special transaction and not a particularly large amount".

The type of equipment, combined with guaranteed anonymity and the ability to pay with large amounts of cash, explains the appeal of spy shops to criminal customers. One can buy equipment that can be used to communicate securely and to monitor others anonymously and without trace. This ensures a high degree of shielding from the authorities, which is attractive to people with criminal backgrounds and intentions. Spy shops choose this clientele in a way, because they can determine their own procedures due to a lack of regulation. As a result of this process, crime is facilitated. Indicative of the awareness of spy shops is the following statement from the manager of one of the spy shops: "I also never know what the beacons we sell are used for. I'm not interested in that either." This indicates that he chooses not to interfere in the affairs of his clients.

Although some people argue that goods sold at spy shops are legal and can also be used for legal activities, there are some interventions to make it harder for criminals to use these goods. Registration of transactions and rejecting huge cash payments are possible ways to prevent criminal clients from turning to spy shops. These measures can be imposed, for instance, through licensing and setting conditions for licenses. In 2019, the city of Amsterdam introduced a licensing requirement for spy shops. In order to get a license, the municipality assesses spy shops and their owners’ integrity. If spy shops or owners do not pass this test, they will not receive a license.

In summary, the literature and analysis show that by guaranteeing anonymity and accepting large cash payments, spy shops create conditions that facilitate crime. As empirical research is scarce, more criminal investigations and criminological research should focus on this specific phenomenon of spy shops and individuals who offer technical equipment and services.

Hitmen

A second important type of facilitator regards hitmen. The principal and the hitman are two important actors in the process of contract killings. The analysis of some liquidation investigations clearly indicates the presence of hitmen. One of the suspects answers the phone with "Hitman, at your service", and has the following conversation “For how much would you shoot somebody? (…) somebody approaches you, 100,000 for yourself?” “a hundred thousand, shit about it.” “Somebody right through his head”. Other investigations provide more indirect clues of a principal and a financial reward.

In all investigations, the suspects were commissioned by an unknown person. This is evident from mutual communication and statements made by the suspects. Several hours after a failed liquidation, two suspects discuss: “those guys weren't happy for sure, hey what do you think?” “No.” “We shouldn't have done him today, mate” This conversation reveals that the principals are not happy with the outcome. One of the suspects is criticized and blamed for his handling of the contract killing and getting rid of the evidence. The suspects clearly were accountable to unknown persons and there was no personal connection between the suspects and the target, which makes a principal a logical explanation. In another investigation, the suspects captured potential victims on camera and video. Audio clips from the video show that they received the target via text message: “He needs that guy; he texted that.” The suspects also don’t know what that target has done or the motive for the liquidation, which makes a principal a plausible option. Finally, one of the other investigations revealed that the suspects were very young, still living with their parents, and without a legal source of income. Nevertheless, they were cruising in rental cars, were in possession of PGPs, and bought beacons for large amounts of cash. Although a principal cannot be identified here with certainty, it seems unlikely that the suspects paid all expenses out of their own pockets. The analysis, therefore, reveals indications in the liquidation investigations of the existence of a principal. However, in many cases it remains difficult to prove (or even unclear) who the principal actually is.

A contract killing is committed in exchange for a (financial) reward. Two of the four liquidation investigations clearly reveal that the suspects receive money for the killings. In mutual conversations, suspects discuss their financial problems, after which one of them receives an advance payment of €500. The context of the conversation shows that this amount will be deducted from the future remuneration after “the thing has been fixed”, which refers to the completion of the contract killing. The other investigation shows the payments in much more detail, namely on paper. A house search results in the seizure of a notebook with the financial housekeeping of the group of suspects. It contains multiple payments to 'hitters' and 'spotters', which range from 25,000 to 100,000 euros. The dates of these payments correspond to the dates of liquidations and liquidation attempts.

This analysis shows the use of facilitators who actually carry out the liquidation, i.e. hitmen. Several clues were found for both principals and financial rewards after liquidations or liquidation attempts. The hitman can be considered a facilitator who is called in because one is unable or unwilling to carry out the offence himself. This has so far proved to be an effective strategy, as the principals often remain anonymous and evidence against them is difficult to gather.

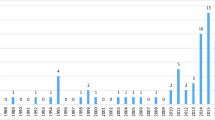

Crime prevention measures

Crime scripts contain former unknown or unseen information, but also provide concrete options for interventions. Figure 1 shows the crime script for contract killings. As stated above, there are multiple goods and facilitators contributing to a successful killing. One type of intervention involves focusing investigative efforts to prevent, disrupt, or discourage the process of killing. Investigating car thieves, for example, may lead to formerly unknown hitmen or targets, since the cars they deliver are used for contract killings. This way, targets can be warned, new investigations can start into criminal groups, and facilitators are not able to deliver much needed goods. Investigating and arresting car thieves is also an even more concrete intervention:

Even though a fast car is legal, the ones used in the investigations were stolen and made anonymous. By complicating the purchase of these stolen cars, a problem arises to obtain multiple cars necessary for the execution of the killing.

Conclusion and discussion

This article aims to contribute to our existing knowledge through a crime script analysis of contract killings, based on six extensively analyzed police investigations in the Netherlands. Starting from a universal crime script, a more specific crime script for contract killings was elaborated. To provide a clear picture of the whole process, the description of the scenes focused on requirements, facilitators, modi operandi, and preparatory actions. A comparison of liquidation investigations was made through a crime script analysis, which resulted in three types of requirements: vehicles, automatic weapons, and technical equipment, including PGP-telephones and beacons. In addition, spy shops played a major role in liquidations as facilitators. Due to a lack of licensing and regulations, the owners of spy shops can decide to a large extent on their own procedures. This leads to the possibility of buying equipment anonymously and with large amounts of cash that facilitates the preparation of liquidations and crime in general. Hitmen are the second type of important facilitators. The analysis revealed that all liquidation investigations contained indications of a principal to whom account had to be held. Two investigations clearly demonstrated financial rewards for contract killings.

This article provides theoretical, methodological, and empirical added value. First, elaboration of a crime script for contract killings adds to the theoretical base of crime script analysis. The systematic review by Dehghanniri and Borrion (2019) shows that the vast majority of this type of research does not focus on organized crime and that applications on contract killings are largely missing. Furthermore, Von Lampe (2011) argues that the application of situational crime prevention theory on organized crime is far more difficult than on high volume crime and street crime. This article, however, shows that application of crime script analysis on contract killings is definitely possible.

Second, the method of crime script analysis was used for analyzing six extensive police investigations. This turned out to be a good method for systematically collecting and analyzing large amounts of information. The elaborated crime script of contract killings might also help future research in this area.

Third, this article resulted in new empirical insights into the process of contract killings, such as requirements and facilitators playing an important role in the successful preparation and commission of these crimes. The important facilitating role of spy shops and technical equipment in particular provide openings for more specific future research as well as crime prevention measures.

This article also has a number of limitations, particularly related to the geographic focus and the types of contract killings that were analyzed. The geographical focus was limited to the Netherlands, particularly the cities of Amsterdam and Utrecht. More research in the Netherlands and abroad might test whether or not these theoretical and empirical insights also apply to other local contexts. A second important limitation relates to the specific contract killings that have been analyzed. All these contract killings failed or were hindered by police interventions. On the one hand, this means that these investigations provided lots of information about the process itself; on the other hand, one might question whether or not more successful contract killings would result in different findings. This could be tested by analyzing more police investigations into both successful and unsuccessful contract killings. However, the ‘Catch 22′ situation of empirical research has to be highlighted. The better the information position of the police (e.g. through informants or by wiretapping and bugging suspects and hitmen), the more likely it is that this ‘guilty knowledge’ will force the police to intervene or warn potential targets (resulting in a failure). Conversely, the most successful contract killings leave no traces, neither for the police nor for empirical research.

Change history

21 June 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-021-09424-z

References

Bijlenga N, Kleemans ER (2018) Criminals seeking ICT-expertise: an exploratory study of Dutch cases. Eur J Crim Policy Res 24(3):253–268

Bullock K, Clarke RV, Tilley N (eds) (2010) Situational Prevention of Organised Crimes. Willan Publishing, Devon

Black JA, Cravens NM (2001) Contracts to kill as scripted behavior. In The diversity of homicide: Proceedings of the 2000 annual meeting of the Homicide Research Working Group. Federal Bureau of Investigation, Washington, pp 83–91

Brayley H, Cockbain E, Laycock G (2011) The value of crime scripting: deconstructing internal child sex trafficking. Policing J Policy Pract 5(2):132–143

Cameron S (2014) Killing for money and the economic theory of crime. Rev Soc Econ 72(1):28–41

Clarke RV (1997) Situational Crime Prevention: Successful Case Studies. Harrow & Heston, Albany

Cornish DB (1994) The procedural analysis of offending and its relevance for situational prevention. Crime Prev Stud 3:151–196

Dehghanniri H, Borrion H (2019) Crime scripting: a systematic review. Eur J Criminol. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370819850943

Hancock G, Laycock G (2010) Organised crime and crime scripts: prospects for disruption. In: Bullock K, Clarke RV, Tilley N (eds) Situational Prevention of Organised Crimes. Willan Publishing, Devon, pp 172–193

Huisman S (2011) De rol van spyshops in de technische afscherming door misdaadondernemers. Korps landelijke politiediensten en Korps Amsterdam-Amstelland (Vertrouwelijk), Woerden

Kleemans ER, Van den Berg EAIM, Van de Bunt HG, Brouwers M, Kouwenberg RF, Paulides G (1998) Georganiseerde criminaliteit in Nederland: Rapportage op basis van de WODC-monitor (Organized crime in the Netherlands. Report based on the WODC-monitor). WODC, The Hague

Kleemans ER, Brienen MEI, van de Bunt HG (2002) Georganiseerde criminaliteit in Nederland (Organized crime in the Netherlands). WODC, The Hague

Leclerc B (2013) New developments in script analysis for situational crime prevention. In: Leclerc B, Wortley R (eds) Cognition and Crime: Offender Decision Making and Script Analyses. Routledge, New York, pp 221–236

MacIntyre D, Wilson D, Yardley E, Brolan L (2014) The British Hitman: 1974-2013. The Howard Journal of Criminal Justice 53(4):325–340

Mouzos J, Venditto J (2003) Contract killings in Australia (Vol. 53). Australian Institute of Criminology, Canberra

Van de Bunt HG, Kleemans ER (2007) Georganiseerde criminaliteit in Nederland (Organized crime in the Netherlands). WODC, The Hague

Van de Port M (2001) Geliquideerd: criminele afrekeningen in Nederland (Liquidated: contract killings in the Netherlands). Meulenhoff, Amsterdam

Van Gestel B, Kouwenberg RF (2019) Update liquidaties 2019 (Update liquidations 2019). Factsheet 2019-3. WODC, The Hague

Van Gestel B, Verhoeven MA (2017) Verkennende voorstudie Liquidaties (preliminary study of liquidations). WODC, The Hague

Von Lampe K (2011) The application of the framework of situational crime prevention to ‘organized crime.’ CriminolCrim Just 11(2):145–163

Acknowledgements

This article is based on a research collaboration between Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (Laura de Korte, MSc, supervised by prof. dr. E.R. Kleemans) and the Dutch National Police. Findings of this research project have been published earlier in Dutch in the journal Justitiële Verkenningen. The authors thank our contact persons at the Dutch National Police and the Dutch Prosecution Service for their help and access to police files.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

There are no potential conflicts of interests and the research did not involve human participants or animals. There is an informed consent from both the National Police and the Dutch Prosecution Service to publish the article.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised due to a retrospective Open Access order.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Korte, L.R., Kleemans, E.R. Contract killings: a crime script analysis. Trends Organ Crim 25, 130–143 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-021-09411-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-021-09411-4