Abstract

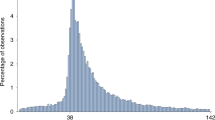

This study tests the evolutionary hypothesis that maternal nutritional condition can influence offspring sex ratio at birth in humans. Using the 1959–1961 Chinese Great Leap Forward famine as a natural experiment, this study combines two large-scale national data sources and difference-in-differences method to identify the effect of famine-induced acute malnutrition on sex ratio at birth. The results show a significant famine-induced decrease in the proportion of male births in the 1958, 1961, and 1964 in the urban population but not in the rural population. Given that both the urban and rural populations suffered from the famine-induced malnutrition, and that the rural population experienced a drastic famine-induced mortality increase and fertility reduction, these results suggest the presence of a short-term famine effect, a long-term famine effect, and a selection effect. The timing of the estimated famine effects suggests that famine influences sex ratio at birth by differential implantation and differential fetal loss by fetal sex.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Despite the fact that the 1982 one-per-thousand fertility survey data is well known for its high-quality and excellent coverage and has been widely used by demographers, it is not publicly available. I gained access to the data during my tenure (2004–2009) at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS). I obtained the data from the State Family Planning Commission (SFPC) for the CASS key research project entitled “The Past, Present, and Future Pattern of Sex Ratio at Birth in China—Some Policy Implications.” I thank both SFPC and CASS for their support of the project.

Using the 1982 fertility survey data, Song (2012) reported a significant decline in the sex ratio at birth between 1960 and 1965 and especially in 1963 and 1964. Zhao et al. (2013) verified the results using the same data. The results do not hold, however, when more recent data, the 1988 fertility survey, are used. However, the 1988 fertility survey was taken in the middle of the one-child family planning policy, which gave people much greater incentive to be “cautious” about reporting their reproductive history information than in 1982, when the policy was in its early stage.

References

Ai, C., & Norton, E. C. (2003). Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Economics Letters, 80(1), 123–129.

Ash, R. (2006). Squeezing the peasants: grain extraction, food consumption and rural living standards in Mao’s China. China Quarterly, 188, 959–998.

Ashton, B., Hill, K., Piazza, A., & Zeitz, R. (1984). Famine in China, 1958–61. Population and Development Review, 10(4), 613–645.

Bereczkei, T., & Dunbar, R. I. M. (1997). Female-biased reproductive strategies in a Hungarian Gypsy population. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 264(1378), 17–22.

Bongaarts, J., & Cain, M. (1981). Demographic response to famine. In K. Cahill (Ed.), Famine (pp. 44–59). New York: Orbis.

Brown, J. (2011). Great leap city: Surviving the famine in Tianjin. In K. E. Manning & F. Wemheuer (Eds.), Eating bitterness: new perspectives on China’s great leap forward and famine (pp. 226–250). Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

Cai, Y., & Wang, F. (2005). Famine, social disruption, and involuntary fetal loss: evidence from Chinese survey data. Demography, 42(2), 301–322.

Chen, Y., & Zhou, L. A. (2007). The long-term health and economic consequences of the 1959–1961 famine in China. Journal of Health Economics, 26, 659–681.

Clarke, K. A. (2005). The phantom menace: omitted variable bias in econometric research. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 22(4), 341–352.

Cramer, J., & Lumey, L. (2011). Maternal preconception diet and the sex ratio. Human Biology, 82(1), 103–107.

Dikötter, F. (2010). Mao’s great famine: The history of China’s most devastating catastrophe, 1958–1962. New York: Walker & Co.

Doblhammer, G., van den Berg, G. J., & Lumey, L. (2013). A re-analysis of the long-term effects on life expectancy of the great Finnish famine of 1866–68. Population Studies, 67(3), 309–322.

Dunning, T. (2012). Natural experiments in the social sciences: A design-based approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fisher, R. A. (1930). The genetical theory of natural selection. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Freedman, D. A. (1991). Statistical models and shoe leather. Sociological Methodology, 21(2), 291–313.

Gibson, M. A., & Mace, R. (2003). Strong mothers bear more sons in rural Ethiopia. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 270(Suppl 1), S108–S109.

Gørgens, T., Meng, X., & Vaithianathan, R. (2012). Stunting and selection effects of famine: a case study of the great Chinese famine. Journal of Development Economics, 97(1), 99–111.

Honaker, J., King, G., & Blackwell, M. (2011). Amelia II: a program for missing data. Journal of Statistical Software, 45(7), 1–47.

Huang, C., Li, Z., Wang, M., & Martorell, R. (2010). Early life exposure to the 1959–1961 Chinese famine has long-term health consequences. Journal of Nutrition, 140(10), 1874.

Imai, K., King, G., & Lau, O. (2008). Toward a common framework for statistical analysis and development. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 17(4), 892–913.

Kannisto, V., Christensen, K., & Vaupel, J. W. (1997). No increased mortality in later life for cohorts born during famine. American Journal of Epidemiology, 145, 987–994.

King, G., Tomz, M., & Wittenberg, J. (2000). Making the most of statistical analyses: improving interpretation and presentation. American Journal of Political Science, 44, 347–361.

Lin, J. Y., & Yang, D. T. (2000). Food availability, entitlements and the Chinese famine of 1959–61. The Economic Journal, 110(460), 136–158.

Mathews, F., Johnson, P. J., & Neil, A. (2008). You are what your mother eats: evidence for maternal preconception diet influencing foetal sex in humans. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 275(1643), 1661–1668.

Mealey, L., & Mackey, W. (1990). Variation in offspring sex ratio in women of differing social status. Ethology and Sociobiology, 11(2), 83–95.

Meng, X., & Qian, N. (2009). The long term consequences of famine on survivors: Evidence from a unique natural experiment using China’s great famine. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 14917.

Meyer, B. D. (1995). Natural and quasi-experiments in economics. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 13(2), 151–161.

Minnesota Population Center. (2010). Integrated public use microdata series, international: Version 6.0 (Machine-readable database). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota.

Murnane, R. J., & Willett, J. B. (2011). Methods matter: Improving causal inference in educational and social science research. New York: Oxford University Press.

Myers, J. H. (1978). Sex ratio adjustment under food stress: maximization of quality or numbers of offspring? American Naturalist, 112(984), 381–388.

Peng, X. (1987). Demographic consequences of the Great Leap Forward in China’s provinces. Population and Development Review, 13(4), 639–670.

Pollet, T. V., Fawcett, T. W., Buunk, A. P., & Nettle, D. (2009). Sex-ratio biasing towards daughters among lower-ranking co-wives in Rwanda. Biology Letters, 5(6), 765.

R Core Team (2012). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. http://www.R-project.org/.

Razzaque, A., Alam, N., Wai, L., & Foster, A. (1990). Sustained effects of the 1974–5 famine on infant and child mortality in a rural area of Bangladesh. Population Studies, 44, 145–154.

Roseboom, T. J., Van der Meulen, J. H. P., Ravelli, A. C. J., Osmond, C., Barker, D. J. P., & Bleker, O. P. (2001). Effects of prenatal exposure to the Dutch famine on adult disease in later life: an overview. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 185(1–2), 93–98.

Rubin, D. (1987). Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: Wiley.

Song, S. (2009). Does famine have a long-term effect on cohort mortality? Evidence from the 1959–1961 Great Leap Forward famine in China. Journal of Biosocial Science, 41(4), 469–491.

Song, S. (2010). Mortality consequences of the 1959–1961 Great Leap Forward famine in China: debilitation, selection, and mortality crossovers. Social Science & Medicine, 71, 551–558.

Song, S. (2012). Does famine influence sex ratio at birth? Evidence from the 1959–1961 Great Leap Forward famine in China. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 279(1739), 2883–2890.

Song, S. (2013a). Assessing the impact of in utero exposure to famine on fecundity: evidence from the 1959–61 famine in China. Population Studies, 67, 293–308.

Song, S. (2013b). Identifying the intergenerational effects of the 1959–1961 Chinese Great Leap Forward famine on infant mortality. Economics and Human Biology, 11(4), 474–487.

Song, S. (2013c). Prenatal malnutrition and subsequent foetal loss risk: evidence from the 1959–1961 Chinese famine. Demographic Research, 29, 707–728.

Song, S. (2014). Evidence of adaptive intergenerational sex ratio adjustment in contemporary human populations. Theoretical Population Biology, 92, 14–21.

Song, S., Wang, W., & Hu, P. (2009). Famine, death, and madness: schizophrenia in early adulthood after prenatal exposure to the Chinese Great Leap Forward famine. Social Science & Medicine, 68(7), 1315–1321.

St Clair, D., Xu, M., Wang, P., Yu, Y., Fang, Y., Zhang, F., et al. (2005). Rates of adult schizophrenia following prenatal exposure to the Chinese famine of 1959–1961. Journal of the American Medical Association, 294(5), 557–562.

State Statistical Bureau. (1991). Statistical yearbook of China 1991. Beijing: State Statistical Press.

Stein, A. D., Barnett, P. G., & Sellen, D. W. (2004a). Maternal undernutrition and the sex ratio at birth in Ethiopia: evidence from a national sample. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 271(Suppl 3), S37–S39.

Stein, A. D., Zybert, P. A., & Lumey, L. (2004b). Acute undernutrition is not associated with excess of females at birth in humans: the Dutch hunger winter. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 271(Suppl 4), S138–S141.

Tamimi, R. M., Lagiou, P., Mucci, L. A., Hsieh, C. C., Adami, H. O., & Trichopoulos, D. (2003). Average energy intake among pregnant women carrying a boy compared with a girl. British Medical Journal, 326(7401), 1245–1246.

Trivers, R. L., & Willard, D. E. (1973). Natural selection of parental ability to vary the sex ratio of offspring. Science, 179(4068), 90–92.

Yang, J. (2012). Tombstone: The great Chinese famine, 1958–1962. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

Zeger, S. L., & Liang, K. Y. (1986). Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics, 42, 121–130.

Zelner, B. A. (2009). Using simulation to interpret results from logit, probit, and other nonlinear models. Strategic Management Journal, 30(12), 1335–1348.

Zhao, Z., Zhu, Y., & Reimondos, A. (2013). Could changes in reported sex ratios at birth during and after China’s 1958–1961 famine support the adaptive sex ratio adjustment hypothesis? Demographic Research, 29, 885–906.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Song, S. Malnutrition, Sex Ratio, and Selection. Hum Nat 25, 580–595 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-014-9208-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-014-9208-1