Abstract

Strong reciprocity is an effective way to promote cooperation. This is especially true when one not only cooperates with cooperators and defects on defectors (second-party punishment) but even punishes those who defect on others (third-party, “altruistic” punishment). Some suggest we humans have a taste for such altruistic punishment and that this was important in the evolution of human cooperation. To assess this we need to look across a wide range of cultures. As part of a cross-cultural project, I played three experimental economics games with the Hadza, who are hunter-gatherers in Tanzania. The Hadza frequently engaged in second-party punishment but they rarely engaged in third-party punishment. Other small-scale societies engaged in less third-party punishment as well. I suggest third-party punishment only became more important in large, complex societies to solve more pressing collective-action problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

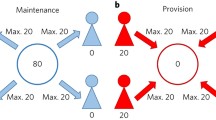

The most P3 can sacrifice is 1/5 of his or her winnings in the TPPG whereas P2 in the UG can theoretically sacrifice any amount from 10% to 100% or, realistically, 4/5 of the total stakes. Thus, second-party punishment can be more costly than third-party punishment in these games. In Tanzania the stakes were 2,000 shillings, so P3 got 1,000 shillings (5 coins). He or she has to choose whether to keep all 5 coins or give me one (200 shillings) to take away 3 (600 shillings) from P1.

People were told they would play games for real money and that, in addition, they would receive a show-up fee, regardless of outcome. All three games involved real money, which the players received in private after the games were finished. I alone gave instructions and played with each player individually in a Land Rover. While waiting to play, people were kept in one area of the camp, and when they finished playing they were sent to another area so they could not influence those waiting to play.

All 62 people played in the same role (either P1 or P2) in the DG and UG. Among those, thirteen P1s in the DG and UG were also P1s in the TPPG and sixteen P2s in the DG and UG were also P2s in the TPPG (one P1 was a P3 in the TPPG and one P2 was a P3 in the TPPG).

P2s rejected low offers more in 2002, perhaps because (unlike in 1998) the strategy method was used; the Hadza just seemed more willing to reject the range of possible, but fictional, offers in 2002 than the one real offer they were presented in 1998 (24% of offers were rejected in 1998, although the mean offer in 1998 UG was higher—33%—and the modal offer was 20%).

Hadza third-party punishment is probably overestimated here. Although I explained the possible outcomes according to our standard protocol, it was difficult for many P3s to see why they should ever want to return 20% of their endowment to me (1 of their 5 coins). When they asked me why they would do so, I simply explained the game again, following our protocol. I did not want to bias them by saying, “You might want to punish P1 because he/she is being stingy, a bad person, and not nice to P2.” Several P3s in the first two days hoped they might end up getting more money if they gave me back some, as if their decision were some sort of gamble. I therefore began to make absolutely sure they understood they would not see any of the money they gave back to me. I began to do this by the end of the second day I played with P3s, and from then on not a single person of the 14 remaining players chose to punish when in the role of P3. Of the 12 P3s who played on the first two days, 5 did not punish offers of zero, but 7 did choose to punish (Table 2). These 7 very likely did not grasp that they would simply be giving up 20% of their endowment for good. Thus, zero might be a truer reflection of Hadza TPPG MAO.

References

Bernhard, H., Fischbacher, U., & Fehr, E. (2006). Parochial altruism in humans. Nature, 442, 912–915.

Bird, R. L. B., & Bird, D. W. (1997). Delayed reciprocity and tolerated theft: the behavioral ecology of food-sharing strategies. Current Anthropology, 38, 49–78.

Blurton Jones, N. G. (1984). Selfish origin for human food sharing: tolerated theft. Ethology and Sociobiology, 5, 1–3.

Blurton Jones, N. G. (1987). Tolerated theft: suggestions about the ecology and evolution of sharing, hoarding, and scrounging. Social Science Information, 26, 31–54.

Boehm, C. (1993). Egalitarian behavior and reverse dominance hierarchy. Current Anthropology, 34, 227–254.

Boehm, C. (1999). Hierarchy in the forest: The evolution of egalitarian behavior. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Boehm, C. (2008). Purposive social selection and the evolution of human altruism. Cross-Cultural Research, 42, 319–352.

Boone, J. L. (1992). Competition, conflict, and the development of social hierarchies. In E. A. Smith & B. Winterhalder (Eds.), Evolutionary ecology and human behavior (pp. 301–337). New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Boyd, R., Gintis, H., Bowles, S., & Richerson, P. J. (2003). The evolution of altruistic punishment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of America, 100, 3531–3535.

Camerer, C. F., & Thaler, R. (1995). Anomalies: dictators, ultimatums, and manners. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9, 209–219.

Endicott, K. (1988). Property, power and conflict among the Batek of Malaysia. In T. Ingold, D. Riches & J. Woodburn (Eds.), Hunters and gatherers: Property, power and ideology (pp. 110–127). Oxford: Berg.

Ensminger, J., Henrich, J., McElreath, R., Barr, A., Barret, C., Bolyanatz, A., et al. (2009). Fairness and punishment in cross-cultural perspective. Submitted for publication.

Fehr, E., & Fischbacher, U. (2004). Third-party punishment and social norms. Evolution and Human Behavior, 25, 63–87.

Fehr, E., & Gachter, S. (2002). Altruistic punishment in humans. Nature, 415, 137–140.

Fehr, E., Fischbacher, U., & Gachter, S. (2002). Strong reciprocity, human cooperation and the enforcement of social norms. Human Nature, 13, 1–25.

Fowler, J. H. (2005). Second-order free-riding problem solved? Nature, 437, e8–e8.

Gintis, H. (2000). Strong reciprocity and human sociality. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 206, 169–179.

Gintis, H., Smith, E. A., & Bowles, S. (2001). Costly signaling and cooperation. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 213, 103–119.

Gintis, H., Bowles, S., Boyd, R., & Fehr, E. (2003). Explaining altruistic behavior in humans. Evolution and Human Behavior, 24, 153–172.

Grimes, B. F. (2000). Ethnologue: Languages of the world. Publication. (Retrieved in 2007 from SIL International, http://www.ethnologue.com/).

Hawkes, K., O’Connell, J. F., & Blurton Jones, N. G. (2001). Hadza meat sharing. Evolution and Human Behavior, 22, 113–142.

Henrich, J. (2000). Does culture matter in economic behavior? Ultimatum game bargaining among the Machiguenga Indians of the Peruvian Amazon. American Economic Review, 90, 973–979.

Henrich, J., Boyd, R., Bowles, S., Gintis, H., Camerer, C., & Fehr, E. (eds). (2004). Foundations of human sociality: Economic experiments and ethnographic evidence from fifteen small-scale societies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Henrich, J., Boyd, R., Bowles, S., Camerer, C., Fehr, E., Gintis, H., et al. (2005). Economic man in cross-cultural perspective: behavioral experiments in 15 small-scale societies. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 28, 795–855.

Henrich, J., McElreath, R., Barr, A., Ensminger, J., Barret, C., Bolyanatz, A., et al. (2006). Costly punishment across human societies. Science, 312, 1767–1770.

Johnson, A. W., & Earle, T. (1987). The evolution of human societies. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

Lee, R. B. (1977). Eating Christmas in the Kalahari. In R. A. Gould (Ed.), Man’s many ways (pp. 13–16). New York: Harper and Row.

Lee, R. B. (1990). Primitive communism and the origin of social inequality. In S. Upham (Ed.), Evolution of political systems: Sociopolitics in small scale sedentary societies (pp. 225–246). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Marlowe, F. W. (2003). A critical period for provisioning by Hadza men: implications for pair bonding. Evolution and Human Behavior, 24, 217–229.

Marlowe, F. W. (2004a). Dictators and ultimatums in an egalitarian society of hunter-gatherers, the Hadza of Tanzania. In J. Henrich, R. Boyd, S. Bowles, H. Gintis, C. Camerer & E. Fehr (Eds.), Foundations of human sociality: Economic experiments and ethnographic evidence from fifteen small-scale societies (pp. 168–193). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Marlowe, F. W. (2004b). What explains Hadza food sharing? Research in Economic Anthropology, 23, 69–88.

Marlowe, F. W. (2006). Central place provisioning: The Hadza as an example. In G. Hohmann, M. Robbins & C. Boesch (Eds.), Feeding ecology in apes and other primates (pp. 359–377). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Marlowe, F. W. (2009). Better to receive than to give: Hadza behavior in three experimental economics games. In J. Ensminger & J. Henrich (Eds.), Fairness and punishment in cross-cultural perspective. Submitted for publication.

Marlowe, F. W., Berbesque, J. C., Barr, A., Barrett, C., Bolyanatz, A., Cardenas, J. C., et al. (2008). More altruistic punishment in larger societies. Proceedings of the Royal Society Biology, 275, 587–590.

Marlowe, F. W., Berbesque, J. C., Barr, A., Barrett, C., Bolyanatz, A., Cardenas, J. C., et al. (2009). The “spiteful” origins of human cooperation. Ms. in preparation.

Mitani, J. C., & Rodman, P. S. (1979). Territoriality: the relation of ranging and home range size to defendability, with an analysis of territoriality among primate species. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 5, 241–251.

Panchanathan, K., & Boyd, R. (2004). Indirect reciprocity can stabilize cooperation without the second-order free rider problem. Nature, 432, 499–502.

Panchanathan, K., & Boyd, R. (2005). Human cooperation: second-order free-riding problem solved? Reply. Nature, 437, e8–e9.

Patton, J. Q. (2000). Reciprocal altruism and warfare. In L. Cronk, N. Chagnon & W. Irons (Eds.), Adaptation and human behavior: An anthropological perspective (pp. 417–436). New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Peterson, N. (1993). Demand sharing: reciprocity and the pressure for generosity among foragers. American Anthropologist, 95, 860–874.

Rockenbach, B., & Milinski, M. (2006). The efficient interaction of indirect reciprocity and costly punishment. Nature, 444, 718–723.

Smith, E. A. (2005). Making it real: interpreting economic experiments. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 28, 832–833.

Tracer, D. P. (1997). Reproductive and socio-economic correlates of maternal hæmoglobin levels in a rural area of Papua New Guinea. Tropical Medicine and International Health, 2, 513–518.

Vehrencamp, S. L. (1983). A model for the evolution of despotic versus egalitarian societies. Animal Behaviour, 31, 667–682.

Wiessner, P. (2005). Norm enforcement among the Ju/’hoansi bushmen: a case of strong reciprocity? Human Nature, 16, 115–145.

Winterhalder, B. (1996). Marginal model of tolerated theft. Ethology and Sociobiology, 17, 37–53.

Woodburn, J. (1998). Sharing is not a form of exchange: an analysis of property-sharing in immediate-return hunter-gatherer societies. In C. M. Hann (Ed.), Property relations: Renewing the anthropological tradition (pp. 48–63). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank Mathew Firestone and Msa Sapo for assistance in running the games. I also wish to thank COSTECH for permission to conduct research in Tanzania, as well as Professor Audax Mabulla, University of Dar es Salaam, for assistance, and the National Science Foundation for funding (grants 0136761 and 0242455). Finally, I am always grateful to the Hadza for their generous hospitality and tolerance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Marlowe, F.W. Hadza Cooperation. Hum Nat 20, 417–430 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-009-9072-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-009-9072-6