Abstract

The main aim of this study is to examine the leading transformations that have occurred throughout the period 2000–2018 in the Spanish publishing industry as a consequence of technological change and its adaptation to the new digital environment. Firstly, this work focuses on the economic importance of Spanish publishing sector studying three key variables: production, employment, and export capacity; secondly, the analysis moves along the structural changes in the Spanish publishing sector through the new millennium, and thirdly, this study discusses on the main business models emerged in the heat of technological disruption. Finally, conclusions close this research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Academic literature establishes the first golden age of the Spanish publishing sector between the years 1900 and 1936 [5]. This period was structurally characterized by a group of small (little capitalized) publishers that not only introduced the latest printing techniques, achieving significant increases of their respective productive capacities but favored the articulation of the value chain in a broad sense by the delimitation and professional separation of the figures of the printer, publisher, and bookseller.

Due to the Spanish Civil War, publishing activity nearly ceased, leaving 80 percent of the Latin American book market without supply. The response was import substitution from countries with higher domestic markets or standards of living. Argentina, Mexico, and Chile expanded their book production to fill the gap and satisfy the demand of an increasingly literate population both in their respective domestic markets and the Spanish-speaking market abroad.

In the 1950s, Spanish publishers set out to regain their prewar status in the Spanish book market. The Franco regime, eager to promote a transatlantic feeling of Hispanicity in this and other cultural spheres, granted subsidies to the industry and legal measures to facilitate production and exports, to the point that censored texts within Spain could be published and distributed abroad.

Between the sixties and first half of the seventies of the aforementioned Franco period, another moment of transformation and relevant change can be located characterized by: (a) new publishing companies that promote the sector to the extent that the normalization of the economic activity of the country is consolidating; (b) a union conscience for the defense of its strategic interests; (c) the recovery of the productive capacity of the companies in the sector; (d) the recognition as a preferred industry by the Franco dictatorship, which allowed the articulation of a strategy for the renewal of the publishing sector through facilities for access to credit for the modernization of production processes or tax relief for export activity, among others, that promoted the internationalization of the publishing sector; (e) the increase in national demand derived from the country’s economic improvement that began in the late 1950s, impacting not only a higher standard of living, but an increasing literacy of the population, which propelled the Spanish publishing sector of the 30th place in 1959 to fifth place in 1974 among the world’s publishing sectors in less than a quarter of a century [1].

With the democratic stage, there is an adjustment of the Spanish editorial fabric. Both the 1982 Mexican debt crisis and the 2001 Argentine crisis hit hard the internationalized Spanish publishers, with a good part of their business in Latin American, which brought the closure of publishing companies, such as Bruguera, or takeovers by other publishing groups. All this will shape the future concentration of the Spanish publishing sector in the nineties of the last century and the early years of the current one. The entry of international publishing groups into the Spanish publishing market, such as Mondadori, Bertelsmann, or Hachette supposed an increasing competition added to the emerging publishing sectoral concentration process in Spain. From a business viewpoint, in this period, the polarization within the Spanish publishing sector was consolidated between the large business groups that controlled a large part of the market and the small publishers [5, 10].

Between the last years of the twentieth century and throughout the twenty-first century, the Spanish publishing sector has not been oblivious to the disruptive effects derived from new technologies, as well as to the notable increase in leisure options of domestic economies, linked -if not, at least in good part- to that digital transformation that has also revolutionized other creative industries, such as film or television.

Regarding challenges posed by innovations and technological changes, those associated with the Internet can be highlighted as follow: (a) a new space for marketing and interaction with potential customers, (b) the emergence of the e-book as a new format for content that can enhance with unsuspected elements (hypertext, music, video, augmented reality, among others) or (c) print-on-demand (POD) as a new production process that liberates publishers from a minimum print run that, otherwise, would end up saturating publishers’ warehouses.

All the phenomena linked to technological change have facilitated a significant reduction—if not an elimination—of the barriers to entry to the sector, which has promoted: (a) the diversification of its offer, thanks to the new entrants; (b) self-publication and (c) the development of new business models.

The study carried out is part of a space not covered from the historiographical perspective, which is none other than analyzing the process of transformation and technological change operated in the Spanish publishing sector from 2000 to 2018. This research aims to understand the impact of technological evolution on the book value chain, and the business models of companies in the sector, besides of enriching the scarce historiography on the Spanish publishing sector from an economic and business viewpoint, occupying its space in the debate on the present and the future of printed culture within the context of new technologies, and allowing a link among publishing activity, new formats, and strategies of commercialization.

The Publishing Sector in the Spanish Economy

The analysis carried out is based on information from secondary sources of information, public and private. The information generated by different organizations in the Spanish publishing sector from 2000 to 2018 was classified, and the data obtained grouped to form different time series that would allow seeing the state and evolution of the Spanish publishing sector throughout this millennium in three key dimensions to understand its relevance: (a) its participation in GDP, (b) its generation of employment, and (c) its export capacity.

GDP Share

Based on the statistical information generated by said Cultural Satellite Account, data related to the publishing sector were isolated, as shown in Fig. 1. As observed, the trend of the contribution of the publishing sector to GDP is downward, as a result of the contraction in demand, forcing a diminishing in print runs per published title and the increase in business mortality. The Great Crisis and the digital transition are behind these impacts.

Source: own elaboration from the Cuenta Satélite de la Cultura en España [Satellite Account of Culture in Spain] (2001–2019) [12]

Evolution of the contribution of books to the cultural GDP and the GDP of Spain (in percentage).

Figure 2 shows the annual evolution of the average circulation of copies by title published in Spain from 2000 to 2018. It is noted a significant diminishing: while in 2000, the average print run was 4440 copies, in 2018, the average circulation barely reach 3762 copies. Nonetheless, in the Spanish publishing market, works with print runs and books that do not reach 1000 copies coexist. The reasons for this reduction in the average print run are in the confluence of several factors: (a) the growth of distribution on-demand; (b) the shortening of the life of the book, and (c) the irruption of the e-book.

Source: own elaboration from the Panorámica de la Edición Española de Libros [Overview of the Spanish Publishing] (2001–2019) [11]

Evolution of the average print run and the number of titles published in Spain (2000–2018).

However, the emergence of more titles on the publishing market, many of them published by a growing number of small publishers, offset the decreasing print runs. In short, more publishers, more titles but fewer copies per each. The main Spanish publishing groups control the market due to its dense and extensive distribution network, as well as its ability to cope with the production of high print runs. However, this capacity has been reduced in the last 3 years, while small and medium-sized publishers appeared on the scene capable of surviving with lower print runs and an average publication of ten titles per year. The diminishing of print runs to fit book demand is cutting, either the oversupply of titles and book returns to publishers. The return of unsold copies is one of the paramount problems for publishers: in some cases, go to foreign markets or, in others, are destroyed instead. Hence, many publishers try to adjust this excess by reducing the average print runs, for instance, implementing the POD model.

Employment Generation

Pending the hardest period of the Great Crisis, the Spanish publishing companies replaced direct employment with the use of external workers through outsourcing, thus controlling labor costs and maintaining profit margins that allowed publishers to continue their activity. It will be from 2013, with the increase in the production of digital books, when the publishers choose to hire technically trained employees to face technological disruption. According to data from the FGEE [4], pending 2018, Spanish publishing companies obtained a total revenue of 2363.90 million euros and generated 12,714 direct jobs and 63,570 indirect jobs. Figure 3 shows the evolution of direct employment in Spanish publishing companies.

The decline in employment in Spanish publishing companies would be explained not only by the negative impact of the Great Crisis on their activity but also by the phenomenon of creative destruction of employment: it is about a process by which the emergence of new products replace others that already exist, making those usual companies and business models in a market disappear. The transition to digital technologies affected trades and professions, which, until relatively recently, were important within publishers. Procedures, until then, highly labor-intensive, become automated, digitized, and employ qualified workers in digitally-based technologies. Thus the process of creative job destruction in the Spanish publishing sector developed.

Export Capacity

The internationalization of Spanish publishers was initially driven by the search for new markets and by the linguistic and cultural advantages, which explains the direct investment made to locate and maintain its Latin American subsidiaries [3]. It is necessary to emphasize that, within the possible routes of the presence of Spanish publishers in foreign markets, the use of subsidiaries was a modality only available to large companies such as Santillana group, Planeta group, Océano group, Urano, SM, Malpaso or Zeta group, among others. The independent publishing companies did not renounce their position in Latin America either, and the formulas applied to position themselves in those markets were mainly three: distribution, sale of rights, and co-publishing.

However, the terrorist attack on the United States on September 11, 2001, marks a turning point in international trade from which Spanish publishing export activity is also not excluded (see Fig. 4). Besides of this explanation, it is possible to point the following ones: a recently released currency, the euro, increasingly appreciated, did not facilitate exchange in international markets; the almost disappearance of the Argentine market, as a result of its severe economic crisis, limiting national export activity to this important market, followed by other countries in the area; the commitment of large Spanish groups to physically position themselves in Latin America by publishing and printing in their target markets; the interest of independent publishing companies to expand their presence beyond national borders through different export strategies, such as co-publishing, distribution or sale of rights, and, finally, the growing interest in the use of distribution platforms and e-commerce.

Source: own elaboration from Comercio Exterior del Libro [Foreign Book Trade] (2001–2019) [2]

Annual evolution of the value of exports of the book sector in Spain from 2000 to 2018 (in millions of euros).

Independent publishers modified their internationalization strategy based on two factors: (a) knowledge of foreign markets, and (b) their financial capacity, going from direct export to a printing program in third countries, in some cases with co-editions with distribution companies. With the virtual distribution and sales platforms developed in the last 5 years, new marketing and export models are being launched, taking advantage of the opportunities presented by POD, which allows publishers to internationalize a title and connect with the leading sales and distribution channels in multiple countries. This initiative represents an opportunity for all publishers whose internationalization or distribution at a global level is unaffordable by traditional media.

All this forms a panorama of a downward adjustment in export activity in the first decade of the 21st century. However, in 2005 the exporting tone of the Spanish publishing sector was restored, but it was short-lived: the Great Crisis made an appearance in 2007 and negatively impacted a change in trend that was reversed again from 2010. However, the improvement in export activity, after having suffered the hardest hit of the crisis and the slow recovery of the Latin American markets, will not come close to the levels reached in 2001.

Sectoral Structure

Throughout the new millennium, the structure of the Spanish publishing sector undergoes a triple transformative process of: (a) atomization, with a myriad of small publishers taking positions in the market space not occupied by large groups, (b) concentration of Much of the market power in a few editorial groups, and (c) adjustment, to adapt to an environment altered by the economic crisis and the emergence of new technologies.

Atomization and Concentration

The millennium brings the beginning of the atomization of the Spanish publishing sector: new publishing companies appear with a clear orientation toward literary creation, some of which -given their ability in attracting literary talent-, were absorbed by large publishing groups.

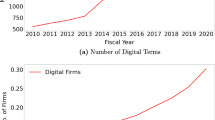

In Spain, there are more than 3000 private equity publishing companies registered, most of which publish less than ten titles per year, of which 26.7% are part of a business group. All this translates into atomization of the sector, the coexistence of a large number of agents with sporadic publications, of short and irregular life, with stable and consolidated publishers, and polarization that is reinforced with the purchase of Editions B and Editions Santillana by Penguin Random House, leaving the industry with two large reference groups: Penguin Random House and Planeta [9]. The small publishing companies consolidated in Spain work with new and differentiated proposals, either: (a) for covering small market niches and neglected by large publishers, (b) for focusing on more or less marginal genres or (c) for presentation the same of books as an aesthetic-artistic object. In the first decade of the 21st century appear a good number of small, independent publishers—this is the case, for example, of Libros del Asteroide, Barataria, Global Rhythm, Impedimenta, Nordic, Peripheral and Sixth Floor, among others- with an evident literary vocation, which sought to cover those spaces generally ignored by large groups. Nonetheless, this process started already in the previous decade with the appearance of publishing companies resulting from almost one-person initiatives such as Carena Editions, Rag Language, or Pages of Foam. This polarization was more accentuated to the extent that there were very few medium-sized publishing companies, such as Anagrama, Tusquets, Salamandra, and a few others (see Fig. 5).

Source: own elaboration from the Panorámica de la Edición Española de Libros [Overview of the Spanish Publishing] (2001–2019) [11]

Annual evolution of the number of publishing companies according to size in Spain from 2000 to 2018.

Along the new millennium, the significant growth of the number of small publishers has to do with some of the following aspects: (a) their thematic specialization; (b) occupy niches that large ones do not, in a fragmented market; (c) publish unknown or novice authors and (d) commitment to careful editions where the continent seeks to live up to the content in terms of materials and design. These publishers are characterized by a small structure, generally one-person authority, with few direct employees and not a high social capital, outsourcing many of their processes (printing, accounting, labor management, and distribution, among others), and not belonging to other business structures. However, despite their small size, taken all together, small publishers have contributed to enriching and energizing the Spanish cultural space.

The process of concentration of publishing companies started in the 1980s is intensified in the following years with acquisitions by larger groups of other small and medium-sized companies with attractive editorial funds, thus replacing traditional business cannibalization with horizontal integration (see Fig. 6). In this way, large publishing conglomerates with an international presence obtain from the small publishers the publishing rights over those works with potential in sales. The recent acquisition of Salamandra, a publishing company located in Barcelona, by the conglomerate Penguin Random House, adds another chapter in the story of the business concentration and the distribution of the business cake between Planeta group and the Spanish division of Penguin Random House.

Digital technology eliminates the geographical limits inherent in print publishing, and the physical distribution channels, associated with traditional publishing models, are altered. Publishing activity in Spain marks a series of trends that have been consolidating in the last two decades: (a) shortening the life cycle of the book on the market; (b) publication of more titles, but with a significant reduction in the average print run; (c) progressive decrease in printed editions, due to a growing commitment to digital edition; (d) increased exports; (e) reduction of both public and private publishers and (f) reduction of the number of copies sold.

Adjustment

The economic crisis and adaptation to new technologies have led to a reduction in both public and private publishing agents. Public agents have disappeared as a consequence of budgetary adjustments made by the central government and autonomous governments as a consequence of budget limitations to meet the deficit of public administrations (see Fig. 7). Private publishers have faced both a continued drop in book demand and technological changes. The digital bet requires an investment of both capital and human resources that is not offset by the turnover from book sales.

Source: own elaboration from the Panorámica de la Edición Española de Libros [Overview of the Spanish Publishing] (2001–2019) [11]

Annual evolution of the number of public and private publishers in Spain from 2000 to 2018.

During 2006, in Spain were sold 230,626,086 copies. Ten years later, the figure stood at 157,233,000 copies. The economic situation in recent years can explain this continuous reduction in the number of copies sold. The diminishing in consumption and internal demand as a consequence of the 2007 economic and financial crisis seems to be the cause of this drop in sales. The Great Crisis was not a reality evidenced until 2009 when the Spanish publishing sector suffered its first drop in the sale of copies (-2.4%), reinforced by factors such: cuts or disappearance of budget allocations for the purchase copies by the network of libraries throughout the country; constrain or suppression of aid to families for the purchase of educational material; a higher number of cultural leisure options linked to digital transformation; the growing e-book piracy, and the loss of points of sale due to the closure of bookstores. Finally, in Spain, bookstores and bookstore chains continue to be the main point of sales for books [10].

The appearance and popularization of the e-book, the development of new editorial business models fully oriented to the digital world, the incorporation of POD, the promotion of the digital distribution and self-publishing platforms and the socialization of reading on digital media, they are laying the groundwork for a reorganization that is not yet complete. In these two last decades, the number of copies sold drop by 32%. Besides, the average print run decreased by almost 41%, from 4619 copies in 2005–2749 in 2016 [9]. Structural changes and adjustments extend throughout the entire value chain: from the very conception of what we call a book to the ways of producing and distributing it, which has implications for existing business models. Next, the research describes the impacts of innovation on the Spanish publishing sector.

New Business Models

The Spanish publishing sector has been able to adapt to the technological changes and continuous innovations that have taken place over the last two decades: from desktop publishing processes to digital printing processes without photosensitive film intermediation, continuing with printing processes known as “direct to plate” (computer to plate), up to the relatively new digital POD and continuing with the publication of digital content on different media, among others. At the same time, Spanish publishers have been readapting their respective business models to properly integrate the changes derived from the innovations adopted [7,10].

New production processes are incorporated, giving rise to new ways of understanding the book, as well as a disconnection of contents from the format. However, not only have innovations taken place in materializing the work, that is, in the chosen medium, but also in production processes: the appearance of POD is also changing the way to produce the printed book.

The publishing sector could not be understood today without connecting process and product innovation. On the one hand, the development of new products, such as the e-book appears on the scene and, on the other hand, the production processes of the book -both on paper and electronic format- are improved, providing not only new features, like augmented reality or POD, among others, but also integrating both design and manufacturing technologies. Among the possible business models that Spanish publishing companies are currently testing, we can highlight fragmented content, payment for consumption or content on-demand, the subscription model, desktop publishing and crowdfunding, the latter being the model that it is significantly expanding more among Spanish publishers [8].

In 2012, Gestión 2000 publishing company, of Planeta group, was pioneered in the commercialization of fragmented content by selling individual book chapters. Subsequently, Random House Mondadori created, within the Debate publishing company, a collection called enDebate to publish non-fiction short texts of about 10,000 words in digital format. The publishing house Páginas de Espuma has incorporated content fragmenting from its digital catalog, creating on its website an online bookstore called relatosrevueltos.com, which offers the possibility of buying the stories of each book separately and designing the content of the book, choosing stories from different books and making personalized anthologies.

Regarding payment for consumption or ‘à la carte’ content, Planeta group launched the Planetahipermedia.com initiative in 2014, a business training website through videos and short textual materials on a specific topic.

The subscription models reached the publishing sector through subscriptions of legal content and with technical books. Today, different generalist platforms in Spain offer this service to the reader, such as 24Symbols, since 2011) and Nubico, since 2013). Subscription reading was launched as a business model in 2011 by the Spanish company 24Symbols, known as the Spotify of books (a motto used by all of its competitors), and widely applauded by the book’s theorists, though it had to fight its way among the distrust of publishers, who offered their books with droppers. Despite its difficulties, 24Symbols expanded its catalog and internationalized, and seen how its model was adopted in Germany, Russia, and the United States (Scribd and Oyster, with great force when obtaining the inclusion of the catalog of two of the greats), and even in Spain, with Nubico (initially Booquo). The appearance of these new subscription platforms was normalizing this use among publishers and readers, who already consider subscription as one more sales channel.

In recent years, publishers and bookstores are firmly committed to making a space in the world of desktop publishing, as one more line of their business. Desktop publishing platforms tied to publishers could redefine the boundaries, hitherto established, between writers and aspiring writers (indie authors) in the world of books, representing a creative disruption within the publishing industry. Bubok is a pioneering online desktop publishing platform that, since 2008, has been able to edit, publish, and sell books on demand, in both paper and digital formats. It is also an online and offline bookstore, which has just recently opened a physical store in Madrid. Roca Editores created in 2012 Rocautores, a digital desktop publishing platform. Roca Editores knew that the classic publishing model was running out and in the wake of initiatives aimed at authors such in the case of Penguin (who created Book Country). For this reason, it went one step further on that path of innovation and experimentation with the creation of Rocautores: a new line of business designed to provide services to authors who need the experience of a professional publisher to self-publish their texts in digital format. Rocautores is a platform where an author can submit his work for evaluation by a team of professionals, receive a reading report and if it is positive, can obtain the editing service: an editor/advisor point out the changes an author must make, and making the necessary style, and orthographic corrections. After editing, the text adapts to the e-Pub format, and the author may request the publication and distribution of his/her work, at no additional cost. Finally, the commercialization of his/her digital work will take place in most national and international stores where e-books in Spanish are selling.

In March 2017, Planeta group launched the Universo de las Letras, a new professional desktop publishing platform that provides service to those who wish to fulfill the dream of seeing their book published. Besides, it will function as an observation platform that encourages the discovery of new authors to value the possible publication of their works under the publishing company of Planeta group that best fits the characteristics of the title.

Some bookstore chains have also been approved by desktop publishing, such as Casa del Libro, since 2013, through Tagus, a platform that allows users to publish their books independently, but with updates and the quality of a traditional publisher. The most successful books in this phase are selected by Ediciones Tagus, which carries out a new professional edition of the book, promotional actions, and may even go as far as making a print run on paper.

Crowdfunding allows financing publishing projects [8], and taking advantage of small proven contributions from a relatively large number of people who need the Internet, without getting into debt with standard financial intermediaries. Crowdfunding has long since spread from the field of ‘startups’ to the world of books. It started with platforms like Verkami, which bring together all kinds of projects, and, unsurprisingly, it has evolved into specialized platforms for desktop publishing projects. But crowdfunding publishing projects have not only enhanced in its specialization but the type of relationship between the independent author and his/her investors.

From 2012 to 2016, crowdfunding has financed projects of a very diverse nature in Spain worth close to 400 million euros, and the trend is that, in the coming years, its use increase. In 2016 alone, crowdfunding raised resources in Spain worth € 101,651,284 compared to € 73,172,388, experiencing a percentage variation of 38.92% [6].

In Spain, there are at least two relevant crowdfunding platforms in the world of books: Libros.com and Pentian.com. The Libros.com platform is a publishing company that ensures quality in editing and design, besides distribution at no cost to the author. Libros.com completely transforms its business model by turning all publishing operations and processes around crowdfunding and offering authors a co-publishing format based on this model. Once a book production is budgeted, the Libros.com announces the investment offer with its corresponding rewards, and if the publishing project obtains the needed funds, then Libros.com proceeds with the publication of the book, sharing with the author 50% royalties. Pentian.com is the platform that has launched this new specialized crowdfunding model for desktop publishing. As in Libros.com, its business consists of the production, distribution, and sale of books, whose funds for the edition have helped to obtain. As in the previous case, it is also an editorial that fully adopts the crowdfunding model: the authors present their works, the patrons support the book, making it possible to publish it, and all share in the benefits of the sales generated. The Pentian.com publishing model shares royalties between the author (40%), the patrons (50%), and the publisher of the same name (10%). The maximum duration of the campaign is 60 days. The patrons become partners of the author, taking benefit from his/her royalties. Nevertheless, they do not influence the decisions about the content of the book or its commercial strategy.

Conclusions and Implications

The technological disruption operated in the two decades studied has had a decisive influence on the changes in the current structure of the Spanish publishing sector, although, today, the old ways of doing publishing business continue to coexist with the new ones. The analysis carried out on the evolution of the Spanish publishing sector throughout the new millennium allows us to point out a series of conclusions.

Firstly, the Spanish publishing sector maintains a significant weight in its contribution to GDP. However, it shows a downward trend due to the contraction in demand that forces a constrain in print runs per published title and added to an increase in business mortality, a product of a lack of financing, and the incapability to face both debt and new publishing projects. All of these effects are a consequence of the Great Crisis, besides the digital transition of the sector. Probably, the current pandemic of Covid-19 would magnify all of these negative impacts.

Secondly, the decrease in employment in Spanish publishing companies has its origin, not only in the Great Crisis but also due to the outsourcing strategy of some processes previously internalized in publishers. Added to all this appears the creative destruction of employment, derived from new business models that require renewed skills and job capabilities.

Third, the export capacity of the Spanish publishing sector, which was initially driven by the possibility of accessing new markets that consumed content in the same language, later, with the Great Crisis, was a fundamental strategy to survive in a convulsed and hostile environment derived from a national market severely damaged in its demand for books. This strategy will be affected by the breakdown of international distribution channels as a consequence of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Fourth, the new millennium offers a structure of the Spanish publishing sector that is atomized and concentrated at the same time, with small specialized publishing companies coexisting with large publishing groups that, to maintain their share of market power, substitute cannibalization for horizontal integration.

Fifth, the Spanish publishing sector presents two lines of business that coexist as complementary and not as substitutes: on the one hand, the paper book and, on the other, the e-book. The latter has not just become a more commercially profitable alternative to the traditional book, but none of the companies in the sector wants to get off the hook on this innovation. Even publishers exclusively oriented to the production of e-books are beginning to emerge. Joint to these reluctances or cautions about the Spanish publishing sector, follow the authors’ interest to continue seeing their work published on paper, and an attitude of the readers to continue betting on the paper book instead of assuming the acquisition of a device of reading e-books. The e-book, rather than being seen as a substitute for the paper book, is being managed by companies in the publishing sector as a compliment and, in this evolution, the POD appears to satisfy the new demands of the market related to the book in Role: (a) quick replacement guarantee; (b) not to lose the sale by dripping and (c) reduction of copies stored by publishers.

Sixth, for the time being, publishers have limited themselves to making a smooth transition between formats and from paper to electronic—in such a way that: (a) both processes still coexist in most publishers, and (b) quickly adopt the change without considering exploiting to the maximum the potential associated with the new format -webs, hyperlinks, augmented reality and videos, among others-. Although digital books are a reality as a product with significant development potential, Spanish publishers act with excessive prudence and caution, which translates into a low proportion between titles published on digital and those on paper. The lack of financial resources and specialized personnel, the fear of digital piracy, the insecurity and uncertainty about what formats and processes will be dominant in the future, and the absence of public policies to support the digital transition can explain that strategy of prudence.

Seventh, the lack of joint digital initiatives by publishing companies makes it easier for new actors from outside the sector, such as Amazon, to have made an appearance on the scene, leading new business models associated with technological changes and, finally, leading Spanish publishers to an assumption of dependence on external innovations that will set the tone and pace of future development of the sector.

Finally, in eighth place, digital publishing will demand from the Spanish publishers an adaptive effort to the new virtual and global marketing context. The emergence of the e-book has meant a redefinition of both the value chain and the editorial distribution channel.

In short, the Spanish publishing sector, only partially, has adequately integrated the innovations derived from the technological changes associated with digitization, and the position adopted by the Spanish publishing sector regarding technological innovation is reactive and not proactive, that is, not intended to lead change but simply adopt it. A series of managerial implications for companies in the publishing sector can also be drawn, outlined below. In the first place, it would be convenient to favor entrepreneurship aimed at creating new companies in the sector that are capable of linking the technological base with creativity and knowledge. In the second place, it would be necessary for many of the companies in the publishing sector to rethink their business model in the face of the transformations and changes in processes and products. Finally, in third place, publishers should rethink their business model, looking for a way to link both realities: the paper book and the digital book. The Spanish publishing companies must be aware that what is truly relevant, what provides added-value is the content, not the format.

References

Catalan J. Building Competitive Advantage: Iberian Book-publishing Industrial Districts between Crisis and Recovery, 1901-2014. Marche et Organisations. 2017;3:137–63.

FEDECALI. Comercio exterior del libro. Madrid: Federación Española de Cámaras del Libro. 2001–2019.

Fernández-Moya, M. La internacionalización del sector editorial español, (1898–2014). Tesis Doctoral, Universidad Complutense de Madrid. 2016; Disponible en https://eprints.ucm.es/40753/1/T38218.pdf.

FGEE. Comercio interior del libro. Madrid: Federación de Gremios de Editores de España (FGEE). 2001–2019.

Gil-Mugarza G. Las letras y los números. La producción española de libros en el siglo XX a través de las fuentes estadísticas. Revista de Historia Industrial. 2014;56:151–87.

González A, Ramos J. Informe anual del crowdfunding en España 2016. Madrid: Universo Crowdfunding; 2017.

Magadán M, Rivas J. Digitization and business models in the Spanish publishing industry. Publ Res Q. 2018;34(3):333–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12109-018-9593-0.

Magadán M, Rivas J. Crowdfunding in the Spanish publishing industry. Publ Res Q. 2019;35(2):187–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12109-019-09643-x.

Magadán M, Rivas J. La adaptación de la industria del libro en España al cambio tecnológico: pasado, presente y futuro de la digitalización. Información, Cultura y Sociedad. 2019;40:31–52. https://doi.org/10.34096/ics.i40.4996.

Magadán, M. Cambio tecnológico e innovación en el sector editorial español: efectos organizativos. Tesis doctoral, Universidad de Oviedo. 2017. http://hdl.handle.net/10651/44590.

Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte. Panorámica de la edición española de libros. Análisis sectorial del libro. Madrid: Secretaría General Técnica. 2001–2019.

Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte. Cuenta satélite de la cultura en España, Madrid. 2001–2019.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Magadán-Díaz, M., Rivas-García, J.I. The Publishing Industry in Spain: A Perspective Review of Two Decades Transformation. Pub Res Q 36, 335–349 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12109-020-09746-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12109-020-09746-w