Abstract

The paper aims at explaining why large-scale energy-intensive industries—here the German iron and steel industry—had a period of slow uptake of major energy-efficient technologies from the mid 1990s to mid 2000s (Arens and Worrell, 2014) and why from the mid 2000s onwards these technologies are increasingly implemented again. We analyze the underlying factors and investment/innovation behavior of individual firms in the German iron and steel industry to better understand barriers and drivers for technological change. The paper gives insights on the decision-making process on energy efficiency in firms and helps to understand how policy affects decision-making. We use a mixed method approach. First, we analyze the diffusion of three energy-efficient technologies (EET) for primary steelmaking from their introduction until today (top-pressure recovery turbine (TRT), basic oxygen furnace gas recovery (BOFGR), and pulverized coal injection (PCI)). We derive the uptake of these technologies both at the national level and at the level of the individual firm. Second, we analyze the impact of drivers and barriers on the decision-making process of individual firms whether or not they want to implement these technologies. Economics and access to capital are the foremost barriers to the uptake of an EET. If the expected payback period exceeds a certain value or if the company lacks capital, investments in EET seem not to happen. But even if an EET is economically viable and the company has access to capital, investments in EET might not be realized. Policy-induced prices might have strengthened the recent diffusion of TRT. We found indications that in a limited number of cases, policy intervention was a driving factor. Technical risks and imperfect information are only marginal factors in our cases. Site-specific factors seem to be important, as site-specific factors shape the economics of the selected EET.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

On November 24, 2010, the European Parliament and the European Council issued the Industrial Emission Directive (2010/75/EU) which came into force on January 11, 2011. In May 2013, the directive was implemented into German law. The implementation of the new requirements occurred in accordance with the Federal Control of Pollution Act (BImSchG) as well as with the directive on the approval procedure (9. BImSchV) (BMU 2013).

Personal communication. Lüngen, HB. VDEh. Heidelberg/Düsseldorf; 26.7.2013.

References

Apeaning, R. W., & Thollander, P. (2013). Barriers to and driving forces for industrial energy efficiency improvements in African industries—a case study of Ghana’s largest industrial area. Journal of Cleaner Production, 53(0), 204–213.

ArcelorMittal. (2012). Leading from the top. The reuse of high pressure flue gas from the top of the blast furnace is reducing Arcelormittal’s carbon footprint—and our energy bill! http://flateurope.arcelormittal.com/flatarchivenews/nov/947. Accessed 20 Oct 2015.

ArcelorMittal. (2014a). The company history—site Ruhrort. http://duisburg.arcelormittal.com/amdu_geschichte.html. Accessed 20 Oct 2015.

ArcelorMittal. (2014b). The company history—site Bremen. http://bremen.arcelormittal.com/694.html. Accessed 20 Oct 2015.

Arens, M., & Worrell, E. (2014). Diffusion of energy efficient technologies in the German steel industry and their impact on energy consumption. Energy, 73(0), 968–977.

Arens, M., Worrell, E., & Schleich, J. (2012). Energy intensity development of the German iron and steel industry between 1991 and 2007. Energy, 45(1), 786–797.

Backlund, S., Thollander, P., Palm, J., & Ottosson, M. (2012). Extending the energy efficiency gap. Energy Policy, 51(0), 392–396.

Brauer, H. (Ed.) (1996). Produktions- und produktintegrierter Umweltschutz. In: Handbuch des Umweltschutzes und der Umweltschutztechnik (in German). Vol. 2. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

Brunke, J.-C., Johansson, M., & Thollander, P. (2014). Empirical investigation of barriers and drivers to the adoption of energy conservation measures, energy management practices and energy services in the Swedish iron and steel industry. Journal of Cleaner Production, 84(0), 509–525.

Bundesamt für Wirtschaft und Ausfuhrkontrollen (BAFA). (2016). Drittlandssteinkohlepreise frei Deutsche Grenze (in German). Eschborn. http://www.bafa.de/bafa/de/energie/steinkohle/drittlandskohlepreis/. Accessed 03 Jun 2016.

Bundesamt für Wirtschaft und Ausfuhrkontrollen (BAFA). (2014). Durch die Besondere Ausgleichsregelung in 2014 begünstigte Abnahmestellen (in German). http://www.bafa.de/bafa/de/energie/besondere_ausgleichsregelung_eeg/publikationen/statistische_auswertungen/besar_2014.xls. Accessed 20 Oct 2015.

Bundesministerium für Justiz und Verbraucherschutz (BMJV). (2014a). Gesetz zum Schutz vor schädlichen Umwelteinwirkungen durch Luftverunreinigungen, Geräusche, Erschütterungen und ähnliche Vorgänge (in German). http://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/bimschg/. Accessed 20 Oct 2015.

Bundesministerium für Justiz und Verbraucherschutz (BMJV). (2014b). Energiesteuergesetz (in German). http://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/energiestg/. Accessed 20 Oct 2015.

Bundesministerium für Justiz und Verbraucherschutz (BMJV). (2014c). Gesetz für den Ausbau Erneuerbarer Energien (in German). http://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/eeg_2014/. Accessed 20 Oct 2015.

Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz und Reaktorsicherheit (BMU). (2006). Nationaler Allokationsplan 2008–2012 für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland (in German). http://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/ets/pre2013/nap/docs/nap_germany_final_en.pdf. Accessed 20 Oct 2015.

Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie (BMWi). (2016). Gesamtausgabe der Energiedaten – Datensammlung des BMWi. Letzte Akutalisierung 19.05.2015. http://www.bmwi.de/DE/Themen/Energie/Energiedaten-und-analysen/Energiedaten/gesamtausgabe. Accessed 03 Jun 2016.

Cagno, E., Worrell, E., Trianni, A., & Pugliese, G. (2013). A novel approach for barriers to industrial energy efficiency. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 19(0), 290–308.

Deutsche Emissionshandelsstelle (DEHSt). (2015). Strompreiskompensation – Hintergrund (in German). http://www.dehst.de/SPK/DE/Strompreiskompensation/Hintergrund/Hintergrund_node.html;jsessionid = A37B66FA0611E0CC5A8C7634D2F38A84.2_cid331. Accessed 20 Oct 2015.

Fleiter, T., Hirzel, S., & Worrell, E. (2012a). The characteristics of energy-efficiency measures—a neglected dimension. Energy Policy, 51(0), 502–513.

Fleiter, T., Schleich, J., & Ravivanpong, P. (2012b). Adoption of energy-efficiency measures in SMEs—an empirical analysis based on energy audit data from Germany. Energy Policy, 51(0), 863–875.

Fleiter, T., Worrell, E., & Eichhammer, W. (2011). Barriers to energy efficiency in industrial bottom-up energy demand models—a review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 15(6), 3099–3111.

Gläser, J., & Laudel, G. (2010). Experteninterviews und qualitative Inhaltsanalyse als Instrumente rekonstruierender Untersuchungen (in German) (4th ed.). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Harris, J., Anderson, J., & Shafron, W. (2000). Investment in energy efficiency: a survey of Australian firms. Energy Policy, 28(12), 867–876.

Hirst, E., & Brown, M. A. (1990). Closing the efficiency gap: barriers to the efficient use of energy. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 267–281.

International Energy Agency (IEA). (2016). Energy statistics of OECD countries. Paris.

Levine, M. D., Koomey, J. G., McMahon, J. E., & Sanstad, A. H. (1995). Energy efficiency policy and market failures. Annual Review of Energy and the Environment, 535–555.

Lise, W., & Kruseman, G. (2008). Long-term price and environmental effects in a liberalised electricity market. Energy Economics, 30(2), 230–248.

Marion, M. (2009). Development of the production and use of converter gas at Saarstahl AG. Stahl und Eisen, 7, 61–67.

Newbery, D. M. (2001). Economic reform in Europe: integrating and liberalizing the market for services. Utilities Policy, 10, 85–97.

Newbery, D. M. (2002). European deregulation, problems of liberalising the electricity industry. European Economic Review, 46, 919–927.

Okazaki, T., & Yamaguchi, M. (2011). Accelerating the transfer and diffusion of energy saving technologies steel sector experience—lessons learned. Energy Policy, 39(3), 1296–1304.

Pollitt, M. G. (2012). The role of policy in energy transitions: lessons from the energy liberalisation era. Energy Policy, 50(0), 128–137.

Remus, R., Monsonet, M. A. A., Roudier, S., & Sancho, L. D. (2013). Best Available Techniques (BAT) reference document for iron and steel production—industrial emissions directive 2010/75/EU (Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. http://eippcb.jrc.ec.europa.eu/reference/BREF/IS_Adopted_03_2012.pdf. Accessed 20 Oct 2015.

Reuters. (2012). S&P cuts ArcelorMittal to ‘BB+’. http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/08/02/idUSWNA253620120802. Accessed 20 Oct 2015.

Rogers, E. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). New York: Free Press.

Rohdin, P., & Thollander, P. (2006). Barriers to and driving forces for energy efficiency in the non-energy intensive manufacturing industry in Sweden. Energy, 31(12), 1836–1844.

Rosenberg, A., Schopp, A., Neuhoff, K., & Vasa, A. (2011). Impact of reductions and exemptions in energy taxes and levies on German industry. CPI Brief. http://www.diw.de/sixcms/detail.php?id = diw_01.c.457174.de. Accessed 20 Oct 2015.

Sardianou, E. (2008). Barriers to industrial energy efficiency investments in Greece. Journal of Cleaner Production, 16(13), 1416–1423.

Schott, R., Malek, C., & Schott, H.-K. (2012). Effizienzsteigerung des Reduktionsmitteleinsatzes im Hochofen zur CO2-Minderung und Kostenersparnis (in German). Chemie Ingenieur Technik 84(7), 1076–1084.

Siemens. (2013). Entspannungsturbine von Siemens – VEO in Eisenhüttenstadt gewinnt Strom aus Gichtgas (in German). https://www.stahleisen.de/Content/News/AktuelleNews/Newsentry/tabid/360/sni%5B847%5D/16263/language/en-US/Default.aspx. Accessed 20 Oct 2015.

Sorrell, S., Schleich, J., Scott, S., O’Malley, E., Trace, F., Boede, U. et al. (2000). Reducing barriers to energy efficiency in public and private organizations. Brighton, UK.

Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis). (2013). BIP-Deflator. Wiesbaden.

Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis). (2016). Preise – Daten zur Energiepreisentwicklung. Lange Reihen von Januar 2000 bis April 2016. Wiesbaden. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Publikationen/Thematisch/Preise/Energiepreise/EnergiepreisentwicklungPDF_5619001.pdf?__blob = publicationFile. Accessed 03 Jun 2016.

Steelinstitute VDEh. (2005–2010). CO 2 -Monitoring-Fortschrittsberichte der Stahlindustrie (in German). Düsseldorf.

Steelinstitute VDEh. (2013). Plantfacts database. Düsseldorf.

Sutherland, R. J. (1991). Market barriers to energy-efficiency investments. The Energy Journal, 12(3), 15–34.

Sutherland, R. J. (1996). The economics of energy conservation policy. Energy Policy, 24(4), 361–370.

Thollander, P., Danestig, M., & Rohdin, P. (2007). Energy policies for increased industrial energy efficiency: evaluation of a local energy programme for manufacturing SMEs. Energy Policy, 35(11), 5774–5783.

Thollander, P., Karlsson, M., Søderstrøm, M., Creutz, D. (2005). Reducing industrial energy costs through energy-efficiency measures in a liberalized European electricity market: case study of a Swedish iron foundry. Applied Energy 81(2), 115–126.

Thollander, P., & Ottosson, M. (2008). An energy efficient Swedish pulp and paper industry: exploring barriers to and driving forces for cost-effective energy efficiency investments. Energy Efficiency 1(1), 21–34.

Trianni, A., & Cagno, E. (2012). Dealing with barriers to energy efficiency and SMEs: some empirical evidences. Energy, 37(1), 494–504.

Trianni, A., Cagno, E., & Worrell, E. (2013). Innovation and adoption of energy efficient technologies: an exploratory analysis of Italian primary metal manufacturing SMEs. Energy Policy, 61(0), 430–440.

Umweltbundesamt (UBA). (2013). Entwicklung der spezifischen Kohlendioxid-Emissionen des deutschen Strommix in den Jahren 1990 bis 2012. Dessau-Roßlau. https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/461/publikationen/climate_change_07_2013_icha_co2emissionen_des_dt_strommixes_webfassung_barrierefrei.pdf. Accessed 03 Jun 2016.

Verein der Kohlenimporteure (VDKI). (2004–2015). Jahresberichte 2004–2015 (in German). Hamburg. http://www.kohlenimporteure.de/archiv-jahresberichte.html. Accessed 03 Jun 2016.

Worldbank. (2016). GDP-Deflator. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.DEFL.KD.ZG. Accessed 03 Jun 2016.

Ziesing, H.-J., Enßlin, C., & Langniß, O. (2001). Stand der Liberalisierung der Energiewirtschaft in Deutschland – Auswirkungen auf den Strom aus Erneuerbaren Energiequellen. FVS Themen, 144–150.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Tobias Fleiter for his valuable remarks. Also, we appreciate the good collaboration with the Steelinstitue VDEh especially with H.-B. Lüngen, M. Sprecher, and R. Hömann.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Data sources for the construction of the timeline of energy prices for the German industry

Calculation of payback periods

The payback periods are calculated according to Eq. (2).

where

PB: payback period

I: investment

P: annual return due to technology i

C: annual O&M cost

i: technology

t: case (Table 4)

k: year

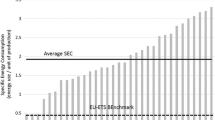

The proceeds for TRT are assumed to equal the market value of generated electricity. This assumes that the company purchases electricity from the public grid and that by applying TRT the company can reduce its electricity consumption from the public grid. Later, we will see that not all steel companies in Germany fulfill this assumption and that TRT in some cases does not compete with the electricity price from the public grid but with the price for on-site electricity generation. Hence, the electricity prices for cases (b) and (c) are (Eq. (3)–(4)):

where

PC: price

EL: electricity

SE: specific emissions

CO2: carbon dioxide

EEG: levy for the support of renewable energies

k: year

a, b: case (Table 4).

For BOFGR, we assume that the recovered BOFG reduces the consumption of natural gas and that in case of EU-ETS costs for the CO2 emissions of that amount of natural gas are saved.

Estimating the economic benefits of PCI, we follow the approach of Schott et al. (2012). Coke is partly replaced by coal in the blast furnace. Differences between the coke and coal price lead to economic benefits. CO2 emission reductions are calculated by accounting coal consumption both in coke ovens and blast furnaces. We assume that 1 t of coke is produced from 1.3 t of coal (Schott et al. 2012). Table 9 lists further assumptions.

The calculations of the proceeds of the respective technologies are given below (Eq. (5)–9).

where

P i: annual return due to technology i

SP: specific production

SR: specific recovery

SE: specific emissions

SC: specific consumption

PC: price

CP: capacity

Q: factor (input to coke oven: coke/coal = 1.6 (Schott et al. 2012)

BF: blast furnace

BOF: basic oxygen furnace

BOFG: basic oxygen furnace gas

CK: coke

CL: coal

CO2: carbon dioxide

EL: electricity

NG: natural gas

OP: without PCI

WP: with PCI

k: year

t: case a, b, or c (Table 4)

a, b, c: cases (Table 4)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Arens, M., Worrell, E. & Eichhammer, W. Drivers and barriers to the diffusion of energy-efficient technologies—a plant-level analysis of the German steel industry. Energy Efficiency 10, 441–457 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12053-016-9465-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12053-016-9465-4