Abstract

Breast carcinoma with neuroendocrine differentiation, also known as neuroendocrine breast carcinoma (NEBC), includes a heterogeneous group of rare tumors, which account for 2–5% of all invasive breast carcinomas. Because of their low incidence, most of the current limited knowledge of these tumors derives from anecdotal case reports or small retrospective series. The diagnosis of NEBC is based on the presence of morphological features similar to gastrointestinal and lung NETs and neuroendocrine markers. NEBCs are usually hormone receptors positive and HER2 negative, but despite this luminal phenotype, most recent studies suggested that NEBC could be associated with worse prognosis compared to invasive breast cancer without neuroendocrine differentiation. Due to its rarity and lack of randomized data, there is little evidence to guide the choice of treatment, so NEBC is currently treated as any invasive breast carcinoma not-otherwise specified. Recently, attempts to molecularly characterize NEBC have been made, in order to provide new targets for a more personalized treatment of this uncommon entity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Breast carcinoma with neuroendocrine differentiation, also known as neuroendocrine breast carcinoma (NEBC), includes a heterogeneous group of rare tumors, which account for 2–5% of all-invasive breast carcinomas [1]. Because of their low incidence, most of the current limited knowledge of these tumors derives from anecdotal case reports or small retrospective series. Their definition, prevalence, and prognosis remain controversial in literature. To date, there is no standard treatment specifically tested in NEBC.

In this review, we summarize the current evidence and the main challenges about epidemiology, histopathological and immunohistochemical features, diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of NEBC. We also discuss new insights and novel potential therapeutic targets, resulting from a better molecular knowledge of this uncommon entity.

Methods

On January 2020, we performed a comprehensive literature review of the PubMed database concerning NEBC using terms “breast” AND (“neuroendocrine differentiation” OR “neuroendocrine carcinoma” OR “neuroendocrine tumor”). The search was limited to articles published in English.

Histopathological and immunohistochemical features

NEBC was first described in 1963 by Feyrter and Hartmann as carcinoid growth pattern within two cases of breast cancer [2]. Later, in 1977, Cubilla and Woodruff classified eight cases of breast cancers as “carcinoid” [3]. Only several years later, in 2003, the World Health Organization (WHO) recognized NEBC as a separate entity of breast cancer, showing morphological characteristics similar to gastrointestinal and pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), with the expression of a neuroendocrine marker in at least 50% of tumor cells [4]. Chromogranin A (CgA) and synaptophysin (Syn) are the most sensitive neuroendocrine markers [5,6,7], whereas neuron-specific enolase (NSE) and CD56 are less sensitive and less specific [8, 9]. In 2012, WHO classification was revised and the threshold value of > 50% of neuroendocrine marker expression in tumor cells was removed, since this cut-off was considered arbitrarily set. According to the 2012 WHO classification, these tumors were categorized into three groups: well differentiated NEBC (NETs, which included low- and intermediate-grade tumors), poorly differentiated NEBC/small cell carcinoma, and NEBC determined by histochemistry or immunohistochemistry (IHC) [1]. The latter category included breast carcinoma of no special type (NST), as well as special type such as solid papillary carcinoma and the hypercellular subtype of mucinous carcinoma. Indeed, as described by Capella et al., the so-called type B of mucinous carcinoma often show neuroendocrine differentiation [10]. According to the 2012 WHO classification, the distinction between NETs and grade 1 or 2 breast carcinomas of other types that show neuroendocrine differentiation was not so clear. For this reason, the key feature of the 2019 WHO classification is the distinction between well-differentiated NETs and poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs), and breast neuroendocrine neoplasms are now categorized as NETs, small cell NECs and large cells NECs [11].

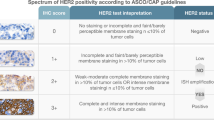

NEBCs are typically hormone receptors (HR) positive and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) negative [12,13,14] (Fig. 1). They can belong to either the luminal A or luminal B molecular subtypes. In 2008, Weigelt et al. described a limited cohort of 6 NEBCs, with 5 cases of luminal A tumor and 1 case of luminal B tumor [12]. In a larger series, Bogine et al. subdivided 112 NEBCs with luminal phenotype as 42% luminal A and 58% luminal B [13]. Similarly, in their series of 47 NEBCs, Lavigne et al. reported 52% of their cases as luminal A and 48% as luminal B [14]. On the other hand, HER2 is only sporadically amplified [15,16,17]. Somatostatin receptors (SSTRs) are G-protein coupled receptors expressed by NET cells at lung, prostate and gastrointestinal level, as well as by ductal breast cancer cells. There are five known subtypes of SSTRs (named SSTR1 to SSTR5), with SSTR2A being the subtype most commonly expressed in breast cancer and being most closely associated with luminal tumors [18,19,20]. Recently, the presence of SSTR2A and SSTR5 has been investigated in NEBCs. Namely, in a retrospective series of 31 cases, the total percentage showing a positive membrane IHC reaction was 71% for both SSTR2A and SSTR5 [21].

Pathological findings in a large cells neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast (WHO [11]). a H&E stain, ×10, b on immunohistochemistry, tumor cells show diffuse positive stain for Chromogranin A (×10), and c estrogen receptors (×10)

Epidemiology

NEBC is a rare entity. The reported prevalence of NEBC among breast cancers varies from 0.1 to 18% [1, 4, 22,23,24]. According to the 2003 classification, the prevalence of these tumors was estimated between 2 and 5%. However, in the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database, only 142 cases of NEBC were identified during the period from 2003 to 2009, which corresponded to a prevalence of < 0.1% [24]. The lack of uniform morphological and immunohistochemical diagnostic criteria may explain the different prevalence reported in the literature.

Similarly to the more frequent types of breast cancer, NEBC is more common in female patients between the sixth and seventh decade of age [24]. However, few cases have been diagnosed even in the premenopausal period [15, 25] or in male patients [26,27,28].

Prognosis

The prognostic implications of neuroendocrine differentiation in breast carcinoma remain controversial. Historically, based on small studies, NEBC was thought to have prognosis similar [22, 23, 29], or even better [30, 31], compared to invasive ductal carcinoma of no special type. However, most recent studies suggested that NEBC could be associated with worse long-term outcomes [24, 32,33,34,35,36]. Among these, the population-based study from SEER database showed that overall survival (OS) and disease-specific survival (DSS) were significantly shorter in NEBC compared with non-NEBC at the same stage [24]. Also a large retrospective study conducted by Zhang et al. showed a higher probability of local recurrence and poorer OS for NEBCs [34]. Of course, the limited number of studies reported in literature and the lack of uniformity in the definition and classification may affect these conflicting results concerning the clinical outcome of NEB. Likewise, some authors investigated the possible impact of histologic subtyping of NEBC according to the 2012 WHO classification on prognosis, providing different evidences. Cloyd et al. showed that small cell carcinoma subtype is associated with worse DSS and OS compared to well-differentiated NECB and invasive carcinoma with neuroendocrine features [36]. More recently, in a small series of 47 patients, Lavigne et al. did not find any statistically significant difference in terms of prognosis between the three subtypes, although OS and progression-free survival (PFS) of the seven poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas were actually worse compared with the other two groups [14].

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of NECB can be challenging. NEBCs have no distinctive presenting signs or symptoms. Very rarely, NEBC can present peculiar clinical features related to hormonal hypersecretion [37]. In fact, anecdotal cases of patients showing symptoms secondary to ectopic secretion of calcitonin, norepinephrine or ACTH have been described in the literature [38,39,40]. Similarly to typical luminal subtypes of breast cancer, NEBC can metastasize to several sites, but more frequently to bone and liver [37, 41].

The imaging findings in patients with NEBC are not specific, and comparable to the ones of other types of breast tumors. Some authors showed that NEBCs may present on mammography as well circumscribed lesions, with no associated microcalcifications, and on ultrasonography, as hypoechogenic mass with irregular morphology and ill-defined margins, with or without cystic component. On magnetic resonance, NECB was described—at least in some cases—as a hypointense irregular lesion on T1-weighted sequences, with early and intense enhancement [42,43,44].

Since the diagnosis of NEBC is based on morphological features and neuroendocrine markers, a biopsy is required for definitive diagnosis. Because of their rarity as primary breast carcinomas, metastasis from another primary neuroendocrine tumor should be always excluded for a differential diagnosis. The presence of a ductal carcinoma in situ component is consistent with the primary nature of the tumor [45].

To exclude a different primary site, a chest and abdomen computed tomography (CT) scan should be performed. Moreover, for the same purpose, a positron emission tomography (PET)-CT with 68Gallium-labeled somatostatin analogs can be performed in the case of well-differentiated NEBC, whereas 18-fluorodeoxyglucose PET-CT could be useful in the case of poorly differentiated NEBC or small carcinomas with a high proliferation rate [46, 47].

Treatment

Due to its rarity and lack of randomized data, there is little evidence to guide the choice of treatment. Consequently, NEBC is currently treated as any invasive breast carcinoma not-otherwise specified.

Surgery is the mainstay of the treatment for early NECB, and the choice of surgical procedure depends on the location of the tumor and on the clinical stage. Since there are no robust data on the role of adjuvant/neoadjuvant therapy in NEBC, it should be prudentially considered according to the same indications adopted for the other types of invasive breast cancer. Likewise, there are no NEBC-specific treatments in the metastatic setting. As for the more common types of breast cancer, treatment strategy should be based on the tumor burden and biological features, as well as the age, menopausal status, general conditions and preferences of the patient [48].

As described above, NEBCs usually exhibit a luminal phenotype; considering that endocrine therapy (ET) has a well-established role in the treatment of HR-positive breast cancer, therefore, it could be a useful tool in the management of NEBCs [49,50,51]. The addition of a cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 4/6 inhibitor to an aromatase inhibitor has significantly changed the prognosis of metastatic patients, both naïve and pre-exposed to ET, providing a great benefit in terms of PFS and, at least in some studies, in terms of OS [52,53,54]. Namely, the combination of palbociclib and fulvestrant has been used in the treatment of a patient affected from NEBC, with positive results [55]. The patient, affected by high-grade NEBC, was refractory to platinum-based chemotherapy as well as first-line hormonal treatment with tamoxifen and leuprolide, but showed a durable response to fulvestrant plus palbociclib.

Everolimus has demonstrated efficacy in well differentiated pancreatic, gastrointestinal and lung NETs [56,57,58]. Further` more, this drug has a specific indication in breast cancer patients, because, in addition to exemestane, it significantly prolonged PFS in metastastic HR positive, HER2-negative breast cancer previously exposed to ET [59]. In light of both these data, a combination of everolimus and exemestane could be an effective treatment option in patients with metastatic luminal well differentiated NEBC.

Anti-HER2 therapy can be used in sporadic cases of NEBC with HER2 overexpression [17].

To date, there is no evidence to select the most effective chemotherapy regimen. The choice of chemotherapy agents can be based on the histopathological features of NEBC. Usually, poorly differentiated or small cell NEBCs have been treated with platinum/etoposide-containing regimes, that is the standard treatment for small cell lung cancer and similar high-grade poorly differentiated neuroendocrine tumors, while anthracyclines and/or taxanes-based chemotherapy have been used for other types of NEBCs [60, 61].

SSTRs are targets for biological therapy in NETs. Somatostatin analogs (SSA) showed an antiproliferative role, providing a prolongation of PFS in small intestinal NETs and they are recommended by international guidelines for the first-line therapy of well-differentiated, G1/2 metastatic NETs [62, 63]. Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT), which consists of a radiolabeled somatostatin analogue, is a novel emerging treatment option for patients with well-differentiated metastatic NETs expressing SSTRs [64, 65]. Similarly to NETs from other sites, SSTRs in NEBC could be a potential therapeutic target [66, 67].

New molecular insights

In the last years, several efforts have been made to identify potential targets for novel therapeutic approaches in NEBC.

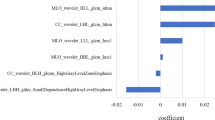

In 2014, a first molecular characterization was provided by Ang et al., who found a PIK3CA mutation in 20% of NEBCs [68]. It seems that NEBCs harbour PIK3CA mutations in a variable percentage, ranging between 7 and 33% [14, 68,69,70], less frequently than common HR positive, HER2 negative breast cancer (up to 45%) [71, 72]. Nevertheless, targeting PIK3CA in metastatic NECB could represent an intriguing therapeutic strategy, given the recent results achieved with the use of alpelisib in a population affected from HR positive, HER2 negative advanced breast cancer [73]. In their recent series, Vranic et al. found a TROP-2 protein expression in 21%, suggesting that a small proportion of NEBCs may be sensitive to target therapy with sacituzumab govitecan [74, 75]. To date, all currently approved biomarkers of response to immune checkpoint inhibitors (PD-L1 expression, high tumor mutational burden and microsatellite instability status) have proven negative, suggesting that patients with NEBC are not ideal candidates for immunotherapy [69, 74] (Table 1).

Conclusions

In summary, NEBC includes a group of rare breast carcinomas, that tend to occur in older women. The diagnosis of NEBC is based on the presence of morphological features similar to gastrointestinal and lung NETs, along with the presence of neuroendocrine markers. Due to its rarity and its recent recognition as a separate entity, the current diagnostic and therapeutic protocol is similar to that of general invasive breast carcinomas. Despite its frequent luminal (A or B) phenotype, most recent studies have reported poorer clinical outcomes for NEBC compared with typical breast carcinomas without neuroendocrine differentiation. Therefore, there is a still unmet need to enhance the ability to identify this uncommon entity, as well as to better know its biology for setting up a more tailored treatment.

References

Lakhani SR, Ellis IO, Schnitt SJ, et al. WHO classification of tumours of the breast, vol. 4. 4th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2012.

Feyrter F, Hartmann G. On the carcinoid growth form of the carcinoma mammae, especially the carcinoma solidum (gelatinosum) mammae. Frankf Z Pathol. 1963;73:24–39.

Cubilla AL, Woodruff JM. Primary carcinoid tumor of the breast: a report of eight patients. Am Surg Pathol. 1997;1:283–92.

Tavassoli FA, Devilee P. World Health Organization Classification of tumours: pathology and genetics of tumours of the breast and female genital organs. Lyon: IARC Press; 2003. p. 32–34.

Bussolati G, Gugliotta P, Sapino A, et al. Chromogranin-reactive endocrine cells in argyrophilic carcinomas (“carcinoids”) and normal tissue of the breast. Am J Pathol. 1985;120(2):186–92.

Portela-Gomes GM, Grimelius L, Wilander E, et al. Granins and granin related peptides in neuroendocrine tumours. Regul Pept. 2010;165:12–20.

Papotti M, Macri L, Finzi G, et al. Neuroendocrine differentiation in carcinoma of the breast: a study of 51 cases. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1989;6:174–88.

Nesland JM, Holm R, Johannessen JV, et al. Neurone specific enolase immunostaining in the diagnosis of breast carcinomas with neuroendocrine differentiation. J Pathol. 1986;148:35–433.

Kawasaki T, Kondo T, Nakazawa T, et al. Is CD56 a specific and reliable neuroendocrine marker for discriminating between endocrine/neuroendocrine ductal carcinoma in situ and intraductal papilloma of the breast? Pathol Int. 2011;61(1):49–51.

Capella C, Eusebi V, Mann B, et al. Endocrine differentiation in mucoid carcinoma of the breast. Histopathology. 1980;4(6):613–30.

WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. WHO classification of tumours of the breast, vol. 4. 5th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2019.

Weigelt B, Horlings HM, Kreike B, et al. Refinement of breast cancer classification by molecular characterization of histological special types. J Pathol. 2008;216:141–50.

Bogina G, Munari E, Brunelli M, et al. Neuroendocrine differentiation in breast carcinoma: clinicopathological features and outcome. Histopathology. 2016;68:422–32.

Lavigne M, Menet E, Tille JC, et al. Comprehensive clinical and molecular analyses of neuroendocrine carcinomas of the breast. Mod Pathol. 2018;31:68–82.

Fujimoto Y, Yagyu R, Murase K, et al. A case of solid neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast in a 40-year-old woman. Breast Cancer. 2007;14:250–3.

Yavas G, Karabagli P, Araz M, et al. HER-2 positive primary solid neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast: a case report and review of the literature. Breast Cancer. 2015;22:432–6.

Gevorgyan A, Bregni G, Galli G, et al. HER2-positive neuroendocrine breast cancer: case report and review of literature. Breast Care. 2016;11:424–6.

Patel YC. Somatostatin and its receptor family. Front Neuroendocrinol. 1999;20:157–98.

Kumar U, Grigorakis SI, Watt HL, et al. Somatostatin receptors in primary human breast cancer: quantitative analysis of mRNA for subtypes 1–5 and correlation with receptor protein expression and tumor pathology. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;92:175–86.

Frati A, Rouzier R, Lesieur B, et al. Expression of somatostatin type-2 and -4 receptor and correlation with histological type in breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:3997–4003.

Terlević R, Perić Baljab M, Tomas D, et al. Somatostatin receptor SSTR2A and SSTR5 expression in neuroendocrine breast cancer. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2019;38:62–6.

Miremadi A, Pinder SE, Lee AH, et al. Neuroendocrine differentiation and prognosis in breast adenocarcinoma. Histopathology. 2002;40:215–22.

Makretsov N, Gilks CB, Coldman AJ, et al. Tissue microarray analysis of neuroendocrine differentiation and its prognostic significance in breast cancer. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:1001–8.

Wang J, Wei B, Albarracin CT, et al. Invasive neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast: a population-based study from the surveillance, epidemiology and end results (SEER) database. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:147–56.

Yoshimura N, Sasada T, Yonehara S. Primary large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast occurring in a pre-menopausal woman. Breast Care. 2015;10:281–3.

Jundt G, Schulz A, Heitz PU, et al. Small cell neuroendocrine (oat cell) carcinoma of the male breast. Immunocytochemical and ultrastructural investigations. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1984;404:213–21.

Papotti M, Tanda F, Bussolati G, et al. Argyrophilic neuroendocrine carcinoma of the male breast. Ultrastruct Pathol. 1993;17:115–21.

Jiang J, Wang G, Lv L, et al. Primary small-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the male breast: a rare case report with review of the literature. Onco Targets Ther. 2014;7:663–6.

van Krimpen C, Elferink A, Broodman CA, et al. The prognostic influence of neuroendocrine differentiation in breast cancer: results of a long-term follow-up study. Breast. 2004;13(4):329–33.

Rovera F, Masciocchi P, Coglitore A, et al. Neuroendocrine carcinomas of the breast. Int J Surg. 2008;6(Suppl. 1):S113–S11515.

Righi L, Sapino A, Marchio C, et al. Neuroendocrine differentiation in breast cancer: established facts and unresolved problems. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2010;27(1):69–766.

Wei B, Ding T, Xing Y, et al. Invasive neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast: a distinctive subtype of aggressive mammary carcinoma. Cancer. 2010;116:4463–73.

Tian Z, Wei B, Tang F, et al. Prognostic significance of tumor grading and staging in mammary carcinomas with neuroendocrine differentiation. Hum Pathol. 2011;42:1169–77.

Zhang Y, Chen Z, Bao Y, et al. Invasive neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast: a prognostic research of 107 Chinese patients. Neoplasma. 2013;60:215–22.

Roininen N, Takala S, Haapasaari K-M, et al. Primary neuroendocrine breast carcinomas are associated with poor local control despite favourable biological profile: a retrospective clinical study. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:72.

Cloyd JM, Yang RL, Allison KH, et al. Impact of histological subtype on long-term outcomes of neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;148:637–44.

Rovera F, Lavazza M, La Rosa S, et al. Neuroendocrine breast cancer: retrospective analysis of 96 patients and review of literature. Int J Surg. 2013;11(S1):S79–83.

Coombes RC, Easty GC, Detre SI, et al. Secretion of immunoreactive calcitonin by human breast carcinomas. BMJ. 1975;4:197–9.

Kaneko H, Hojo H, Ishikawa S, et al. Norepinephrine-producing tumors of bilateral breasts: a case report. Cancer. 1978;41:2002–7.

Woodard BH, Eisenbarth G, Wallace NR, et al. Adrenocorticotropin production by a mammary carcinoma. Cancer. 1981;47:1823–7.

Manes K, Delis S, Papaspyrou N, et al. Neuroendocrine breast carcinoma metastatic to the liver: report of a case and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2014;5:540–3.

Günhan-Bilgen I, Zekioglu O, Ustün EE, et al. Neuroendocrine differentiated breast carcinoma: imaging features correlated with clinical and histopathological findings. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:788–93.

Chang ED, Kim MK, Kim JS, et al. Primary neuroendocrine tumor of the breast: imaging features. Korean J Radiol. 2013;14(3):395e9.

Yoon YS, Kim SY, Lee JH, et al. Primary neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast: Radiologic and pathologic correlation. Clin Imaging. 2014;38:734–8.

Hoang MP, Maitra A, Gazdar AF, et al. Primary mammary small-cell carcinoma: a molecular analysis of 2 cases. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:753–7.

Sundin A, Arnold R, Baudin E, et al. Antibes Consensus Conference participants. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the standards of care in neuroendocrine tumors: radiological, nuclear medicine & hybrid imaging. Neuroendocrinology. 2017;105(3):212–44.

Anirban M, Sellam K, Suhas S, et al. 68Ga DOTANOC PET/CT in primary neuroendocrine tumor of the breast. Clin Nucl Med. 2014;39(4):396–8.

Cardoso F, Senkus E, Costa A, et al. 4th ESO-ESMO International Consensus Guidelines for Advanced Breast Cancer (ABC 4)†. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:1634–57.

Buttar A, Mittal K, Khan A, et al. Effective role of hormonal therapy in metastatic primary neuroendocrine breast carcinoma. Clin Breast Cancer. 2011;11:342–5.

Alkaied H, Harris K, Azab B, et al. Primary neuroendocrine breast cancer, how much do we know so far? Med Oncol. 2012;29:2613–8.

Pagano M, Asensio SN, Zanelli F, et al. Is there a role for hormonal therapy in neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast? A Paradigmatic case report. Clin Breast Cancer. 2014;14(5):e99–e101.

Turner NC, Ro J, André F, et al. Palbociclib in hormone-receptor–positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:209–19.

Hortobagyi GN, Stemmer SM, Burris HA, et al. Ribociclib as first-line therapy for HR—positive, advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1738–48.

Slamon DJ, Neven P, Chia S, et al. Overall survival with ribociclib plus fulvestrant in advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(6):514–24.

Shanks A, Choi J, Karur V. Dramatic response to cyclin D–dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor in refractory poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2018;31(3):352–4.

Yao JC, Phan AT, Chang DZ, et al. Efficacy of RAD001 (everolimus) and octreotide LAR in advanced low- to intermediate-grade neuroendocrine tumors: results of a phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4311–8.

Fazio N, Granberg D, Grossman A, et al. Everolimus plus octreotide LAR in patients with advanced lung neuroendocrine tumors: analysis of the phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled RADIANT-2 study. Chest. 2013;143(4):955–62.

Yao JC, Fazio N, Singh S, et al. Everolimus for the treatment of advanced, non-functional neuroendocrine tumours of the lung orgastrointestinal tract (RADIANT-4): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2016;387(10022):968–77.

Baselga J, Campone M, Piccart M, et al. Everolimus in postmenopausal hormone-receptor–positive advanced breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:520–9.

Angarita FA, Rodríguez JL, Meek E, et al. Locally advanced primary neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast: case report and review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:128–38.

Wei X, Chen C, Xi D, et al. A case of primary neuroendocrine breast carcinoma that responded to neo-adjuvant chemotherapy. Front Med. 2015;9:112–6.

Rinke A, Muller HH, Schade-Brittinger C, et al. Placebo-controlled, double-blind, prospective, randomized study on the effect of octreotide LAR in the control of tumor growth in patients with metastatic neuroendocrine midgut tumors: a report from the PROMID study group. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4656–63.

Caplin ME, Pavel M, Ćwikła JB, et al. Anti-tumour effects of lanreotide for pancreatic and intestinal neuroendocrine tumours: the CLARINET open-label extension study. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2016;23(3):191–9.

Kim SJ, Pak K, Koo PJ, et al. The efficacy of (177)Lu-labelled peptide receptor radionuclide therapy in patients with neuroendocrine tumours: a meta-analysis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;42(13):1964–70.

Strosberg J, El-Haddad G, Wolin E, et al. NETTER-1 Trial Investigators. Phase 3 Trial of 177Lu-Dotatate for Midgut Neuroendocrine Tumors. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(2):125–35.

Rischke HC, Staib-Sebler E, Mose S, et al. Metastatic breast carcinoma with neuroendocrine differentiation–its combined therapy with tamoxifen and the somatostatin analog octreotide. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1999;124(7):182–6.

Savelli G, Zaniboni A, Bertagna F, et al. Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) in a patient affected by metastatic breast cancer with neuroendocrine differentiation. Breast Care (Basel). 2012;7:408–10.

Ang D, Ballard M, Beadling C, et al. Novel mutations in neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast: Possible therapeutic targets. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2015;23:97–103.

McCullar B, Pandey M, Yaghmour G, et al. Genomic landscape of small cell carcinoma of the breast contrasted to small cell carcinoma of the lung. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;158:195–202.

Marchio C, Geyer FC, Ng CK, et al. The genetic landscape of breast carcinomas with neuroendocrine differentiation. J Pathol. 2017;241:405–19.

Saal LH, Holm K, Maurer M, et al. PIK3CA mutations correlate with hormone receptors, node metastasis, and ERBB2, and are mutually exclusive with PTEN loss in human breast carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2554–9.

The Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2012;490(7418):61–70.

André F, Ciruelos E, Rubovszky G, et al. Alpelisib for PIK3CA mutated, hormone receptor–positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1929–40.

Vranic S, Palazzo J, Sanati S, et al. Potential novel therapy targets in neuroendocrine carcinomas of the breast. Clin Breast Cancer. 2019;19(2):131–6.

Bardia A, Mayer IA, Diamond JR, et al. Efficacy and safety of anti-trop-2 antibody drug conjugate sacituzumab govitecan (IMMU-132) in heavily pretreated patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2141–8.

Nicoletti S, Papi M, Drudi F, et al. Small cell neuroendocrine tumor of the breast in a 40 year-old woman: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:201.

Christie M, Chin-Lenn L, Watts MM, et al. Primary small cell carcinoma of the breast with TTF-1 and neuroendocrine marker expressing carcinoma in situ. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2010;3(6):629–33.

Latif N, Rosa M, Samian L, et al. An unusual case of primary small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast. Breast J. 2010;16(6):647–51.

Nozoe T, Sueishi K, Mori E, et al. Primary neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast: report of a case. Surg Today. 2011;41:829–31.

Honami H, Sotome K, Sakamoto G, et al. Synchronous bilateral neuroendocrine ductal carcinoma in situ. Breast Cancer. 2014;21:508–13.

Zhang JY, Chen WJ. Bilateral primary breast neuroendocrine carcinoma in a young woman: report of a case. Surg Today. 2011;41(11):1575–8.

Yildirim Y, Elagoz S, Koyuncu A, et al. Management of neuroendocrine carcinomas of the breast: a rare entity. Oncol Lett. 2011;2(5):887–90.

Watrowski R, Jäger C, Matten D, et al. Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast–diagnostic and clinical implications. Anticancer Res. 2012;32(11):5079–82.

Su CH, Chang H, Chen CJ, et al. The carcinoembryonic antigen as a potential prognostic marker for neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast. Anticancer Res. 2012;32(1):183–8.

Menéndez P, García E, Rabadán L, et al. Primary neuroendocrine breast carcinoma. Clin Breast Cancer. 2012;12(4):300–3.

Psoma E, Nikolaidou O, Stavrogianni T, et al. A rare case report of a primary large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast with coexisting Paget disease. Clin Imaging. 2012;36(5):599–660.

Hanna MY, Leung E, Rogers C, et al. Primary large-cell neuroendocrine tumor of the breast. Breast J. 2013;19(2):204–6.

Tajima S, Horiuchi H. Neuroendocrine tumor, well differentiated, of the breast: a relatively high-grade case in the histological subtype. Case Rep Pathol. 2013;2013:204065.

Bozkurt MA, Kocataş A, Özkan Y, et al. A rare entity of breast cancer: primary neuroendocrin carcinoma. J Breast Health. 2014;10(4):242–4.

Adams RW, Dyson P, Barthelmes L. Neuroendocrine breast tumours: breast cancer or neuroendocrine cancer presenting in the breast? Breast. 2014;23(2):120–7.

Sherwell-Cabello S, Maffuz-Aziz A, Hernández-Hernández B, et al. Primary neuroendocrine tumor of the breast. Breast J. 2015;21(3):312–3.

Janosky M, Bian J, Dhage S, et al. Primary large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast, a case report with an unusual clinical course. Breast J. 2015;21(3):303–7.

Collado-Mesa F, Net JM, Klevos GA, et al. Primary neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast: report of 2 cases and literature review. Radiol Case Rep. 2017;12(1):1–12.

Soe AM, Joseph G, Guevara E, et al. Primary neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast metastatic to the bones, which chemotherapy? Breast J. 2017;23(5):589–93.

Tremelling A, Samuel S, Murray M. Primary small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast—a case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2017;38:29–31.

Abou Dalle I, Abbas J, Boulos F, et al. Primary small cell carcinoma of the breast: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2017;11(1):290.

Bergstrom C, Porembka J, Fang Y, et al. Primary neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast. Breast J. 2019;25(3):519–20.

Valente I, Tringali G, Martella EM, et al. Primary neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast: a case report of liver and lymph node metastases after eight years from diagnosis. Breast J. 2020;26(3):505–7.

Kawasaki T, Hasebe T, Oiwa M, et al. Invasive carcinoma with neuroendocrine differentiation of the breast showing triple negative, large and basal cell-like features. Pathol Int. 2019;69(8):502–4.

Acknowledgments

Open access funding provided by Universitã degli Studi di Torino within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

ET, ALS, LD, MPB, GDR have no conflict of interest to declare. GVS received honoraria, research funding and had roles as consultant or advisor for Roche, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Lilly Pharma and MSD. MDM received honoraria and had roles as consultant or advisor for AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, MSD, Eisai, Takeda, Pfizer and Janssen.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Trevisi, E., La Salvia, A., Daniele, L. et al. Neuroendocrine breast carcinoma: a rare but challenging entity. Med Oncol 37, 70 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-020-01396-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-020-01396-4