Abstract

Background

Restoration of brain tissue perfusion is a determining factor in the neurological evolution of patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) and hemorrhagic shock (HS). In a porcine model of HS without neurological damage, it was observed that the use of fluids or vasoactive drugs was effective in restoring brain perfusion; however, only terlipressin promoted restoration of cerebral oxygenation and lower expression of edema and apoptosis markers. It is unclear whether the use of vasopressor drugs is effective and beneficial during situations of TBI. The objective of this study is to compare the effects of resuscitation with saline solution and terlipressin on cerebral perfusion and oxygenation in a model of TBI and HS.

Methods

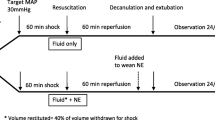

Thirty-two pigs weighing 20–30 kg were randomly allocated into four groups: control (no treatment), saline (60 ml/kg of 0.9% NaCl), terlipressin (2 mg of terlipressin), and saline plus terlipressin (20 ml/kg of 0.9% NaCl + 2 mg of terlipressin). Brain injury was induced by lateral fluid percussion, and HS was induced through pressure-controlled bleeding, aiming at a mean arterial pressure (MAP) of 40 mmHg. After 30 min of circulatory shock, resuscitation strategies were initiated according to the group. The systemic and cerebral hemodynamic and oxygenation parameters, lactate levels, and hemoglobin levels were evaluated. The data were subjected to analysis of variance for repeated measures. The significance level established for statistical analysis was p < 0.05.

Results

The terlipressin and saline plus terlipressin groups showed an increase in MAP that lasted until the end of the experiment (p < 0.05). There was a notable increase in intracranial pressure in all groups after starting treatment for shock. Cerebral perfusion pressure and cerebral oximetry showed no improvement after hemodynamic recovery in any group. The groups that received saline at resuscitation had the lowest hemoglobin concentrations after treatment.

Conclusions

The treatment of hypotension in HS with saline and/or terlipressin cannot restore cerebral perfusion or oxygenation in experimental models of HS and severe TBI. Elevated MAP raises intracranial pressure owing to brain autoregulation dysfunction caused by TBI.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Shackford SR. The epidemiology of traumatic death. Arch Surg. 1993;128:571.

Champion HR, Copes WS, Sacco WJ, Lawnick MM, Keast SL, Frey CF. The Major trauma outcome study. J Trauma Injury Infect Crit Care. 1990;30:1356–65.

Heckbert SR, Vedder NB, Hoffman W, Winn RK, Hudson LD, Jurkovich GJ, et al. Outcome after hemorrhagic shock in trauma patients. J Trauma Injury Infect Crit Care. 1998;45:545–9.

Chesnut RM, Chesnut RM, Marshall LF, Klauber MR, Blunt BA, Baldwin N, et al. The role of secondary brain injury in determining outcome from severe head injury. J Trauma Injury Infect Crit Care. 1993;34:216–22.

Marmarou A, Anderson RL, Ward JD, Choi SC, Young HF, Eisenberg HM, et al. Impact of ICP instability and hypotension on outcome in patients with severe head trauma. J Neurosurg. 1991;75:S59-66.

Lipsky AM, Gausche-Hill M, Henneman PL, Loffredo AJ, Eckhardt PB, Cryer HG, et al. Prehospital hypotension is a predictor of the need for an emergent, therapeutic operation in trauma patients with normal systolic blood pressure in the emergency department. J Trauma Injury Infect Crit Care. 2006;61:1228–33.

Unterberg AW, Stover J, Kress B, Kiening KL. Edema and brain trauma. Neuroscience. 2004;129(4):1021–9.

Stocchetti N, Carbonara M, Citerio G, Ercole A, Skrifvars MB, Smielewski P, et al. Severe traumatic brain injury: targeted management in the intensive care unit. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:452–64.

Dutton RP, Mackenzie CF, Scalea TM. Hypotensive resuscitation during active hemorrhage; impact on in-hospital mortality. J Trauma. 2002;52(6):1141–6.

Gantner D, Moore EM, Cooper DJ. Intravenous fluids in traumatic brain injury: what’s the solution? Curr Opin Crit Care. 2014;20:385–9.

Alam HB, Stanton K, Koustova E, Burris D, Rich N, Rhee P. Effect of different resuscitation strategies on neutrophil activation in a swine model of hemorrhagic shock. Resuscitation. 2004;60:91–9.

Gil-Anton J, Mielgo VE, Rey-Santano C, Galbarriatu L, Santos C, Unceta M, et al. Addition of terlipressin to initial volume resuscitation in a pediatric model of hemorrhagic shock improves hemodynamics and cerebral perfusion. PLoS. 2020;15(7): e0235084.

Stadlbauer KH, Wagner-Berger HG, Wenzel V, Voelckel WG, Krismer AC, Klima G, et al. Survival with full neurologic recovery after prolonged cardiopulmonary resuscitation with a combination of vasopressin and epinephrine in pigs. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:1743–9.

Ida KK, Otsuki DA, Sasaki ATC, Borges ES, Castro LUC, Sanches TR, et al. Effects of terlipressin as early treatment for protection of brain in a model of haemorrhagic shock. Crit Care. 2015;19:1–14.

Ida KK, Chisholm KI, Malbouisson LMS, Papkovsky DB, Dyson A, Singer M, et al. Protection of cerebral microcirculation, mitochondrial function, and electrocortical activity by small-volume resuscitation with terlipressin in a rat model of haemorrhagic shock. Br J Anaesth. 2018;120:1245–54.

Katz PS, Molina PE. A lateral fluid percussion injury model for studying traumatic brain injury in rats. Methods Mol Biol. 2018;1717:27–36.

Morales DM, Marklund N, Lebold D, Thompson HJ, Pitkanen A, Maxwell WL, et al. Experimental models of traumatic brain injury: do we really need to build a better mousetrap? Neuroscience. 2005;136:971–89.

Bootsma IT, Boerma EC, de Lange F, Scheeren TWL. The contemporary pulmonary artery catheter. Part 1: placement and waveform analysis. J Clin Monit Comput. 2022;36(1):5–15.

Muir WW, Hughes D, Silverstein DC. Fluid therapy in animals: physiologic principles and contemporary fluid resuscitation considerations. Front Vet Sci. 2021;8:744080.

Fritz HG, Walter B, Holzmayr M, Brodhun M, Patt S, Bauer R. A pig model with secondary increase of intracranial pressure after severe traumatic brain injury and temporary blood loss. J Neurotrauma. 2005;22:807–21.

American College of Surgeons. The Commetee on Trauma. Student Course Manual ATLS ® Advanced Trauma Life Support ®. 10th ed. Chicago: American College of Surgeons; 2018.

Bootsma IT, Boerma EC, Scheeren TWL, de Lange F. The contemporary pulmonary artery catheter. Part 2: measurements, limitations, and clinical applications. J Clin Monit Comput. 2022;36(1):17–31.

Cochran WG, Chambers SP. The planning of observational studies of human populations. J R Stat Soc Ser A. 1965;128(2):234–66.

Cecconi M, de Backer D, Antonelli M, Beale R, Bakker J, Hofer C, et al. Consensus on circulatory shock and hemodynamic monitoring. Task force of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40:1795–815.

Kashani K, Omer T, Shaw AD. The intensivist’s perspective of shock, volume management, and hemodynamic monitoring. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022;17:706–16.

Leech C, Turner J. Shock in trauma. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2023;41:1–17.

Lambden S, Creagh-Brown BC, Hunt J, Summers C, Forni LG. Definitions and pathophysiology of vasoplegic shock. Crit Care. 2018;22:1–8.

Sequeira V, van der Velden J. The Frank–Starling law: a jigsaw of titin proportions. Biophys Rev. 2017;9:259–67.

Tsuneyoshi I, Onomoto M, Yonetani A, Kanmura Y. Low-dose vasopressin infusion in patients with severe vasodilatory hypotension after prolonged hemorrhage during general anesthesia. J Anesth. 2005;19:170–3.

Voelckel WG, Convertino VA, Lurie KG, Karlbauer A, Schöchl H, Lindner K-H, et al. Vasopressin for hemorrhagic shock management: revisiting the potential value in civilian and combat casualty care. J Trauma Injury Infect Crit Care. 2010;69:S69-74.

Stadlbauer KH, Wagner-Berger HG, Raedler C, Voelckel WG, Wenzel V, Krismer AC, et al. Vasopressin, but not fluid resuscitation, enhances survival in a liver trauma model with uncontrolled and otherwise lethal hemorrhagic shock in pigs. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:699–704.

Morelli A, Ertmer C, Rehberg S, Lange M, Orecchioni A, Cecchini V, et al. Continuous terlipressin versus vasopressin infusion in septic shock (TERLIVAP): a randomized, controlled pilot study. Crit Care. 2009;13:1–14.

Haas T, Fries D, Holz C, Innerhofer P, Streif W, Klingler A, et al. Less impairment of hemostasis and reduced blood loss in pigs after resuscitation from hemorrhagic shock using the small-volume concept with hypertonic saline/hydroxyethyl starch as compared to administration of 4% gelatin or 6% hydroxyethyl starch solution. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:1078–86.

Wang A, Ortega-Gutierrez S, Petersen NH. Autoregulation in the neuro ICU. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2018;20:1–15.

Donnelly JE, Young AMH, Brady K. Autoregulation in paediatric TBI-current evidence and implications for treatment. Childs Nerv Syst. 2017;33:1735–44.

Zeiler FA, Mathieu F, Monteiro M, Glocker B, Ercole A, Cabeleira M, et al. Systemic markers of injury and injury response are not associated with impaired cerebrovascular reactivity in adult traumatic brain injury: a collaborative European neurotrauma effectiveness research in traumatic brain injury (CENTER-TBI) study. J Neurotrauma. 2021;38:870–8.

Gomez A, Sekhon M, Griesdale D, Froese L, Yang E, Thelin EP, et al. Cerebrovascular pressure reactivity and brain tissue oxygen monitoring provide complementary information regarding the lower and upper limits of cerebral blood flow control in traumatic brain injury: a Canadian high resolution-TBI (CAHR-TBI) cohort study. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2022;10:54.

Lattanzi S, Słomka A, Divani AA. Blood pessure variability and cerebrovascular reactivity. Am J Hypertens. 2023;36(1):19–20.

Xu S, Lu J, Shao A, Zhang JH, Zhang J. Glial cells: role of the immune response in Ischemic Stroke. Front Immunol. 2020;11:294.

Mira RG, Lira M, Cerpa W. Traumatic brain injury: mechanisms of glial response. Front Physiol. 2021;12:740939.

Mathieu F, Zeiler FA, Whitehouse DP, Das T, Ercole A, Smielewski P, et al. Relationship between measures of cerebrovascular reactivity and intracranial lesion progression in acute TBI patients: an exploratory analysis. Neurocrit Care. 2020;32:373–82.

Czosnyka M, Smielewski P, Lavinio A, Czosnyka Z, Pickard JD. A synopsis of brain pressures: Which? When? Are they all useful? Neurol Res. 2007;29:672–9.

Heldt T, Zoerle T, Teichmann D, Stocchetti N. Intracranial pressure and intracranial elastance monitoring in neurocritical care. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2019;21:523–49.

Brasil S, Frigieri G, Taccone FS, Robba C, Solla DJF, de Carvalho NR, et al. Noninvasive intracranial pressure waveforms for estimation of intracranial hypertension and outcome prediction in acute brain-injured patients. J Clin Monit Comput. 2022;37:753–60.

Rodríguez-Boto G, Rivero-Garvía M, Gutiérrez-González R, Márquez-Rivas J. Basic concepts about brain pathophysiology and intracranial pressure monitoring. Neurologia. 2015;30:16–22.

Eide PK, Sorteberg W. Association among intracranial compliance, intracranial pulse pressure amplitude and intracranial pressure in patients with intracranial bleeds. Neurol Res. 2007;29:798–802.

Feldman Z, Robertson CS. Monitoring of cerebral hemodynamics with jugular bulb catheters. Crit Care Clin. 1997;13:51–77.

Gopinath SP, Valadka AB, Uzura M, Robertson CS. Comparison of jugular venous oxygen saturation and brain tissue PO2 as monitors of cerebral ischemia after head injury. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:2337–45.

Vincent JL. Determination of oxygen delivery and consumption versus cardiac index and oxygen extraction ratio. Crit Care Clin. 1996;12:995–1006.

Le Roux P. Physiological monitoring of the severe traumatic brain injury patient in the intensive care unit. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2013;13(3):331.

Veenith TV, Carter EL, Geeraerts T, Grossac J, Newcombe VFJ, Outtrim J, et al. Pathophysiologic mechanisms of cerebral ischemia and diffusion hypoxia in traumatic brain injury. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73(5):542–50.

Fecher A, Stimpson A, Ferrigno L, Pohlman TH. The pathophysiology and management of hemorrhagic shock in the polytrauma patient. J Clin Med. 2021;10(20):4793.

Spinella PC, Cap AP. Whole blood: back to the future. Curr Opin Hematol. 2016;23:536–42.

Holcomb JB, Jenkins DH. Get ready: whole blood is back and it’s good for patients. Transfusion (Paris). 2018;58:1821–3.

Gobatto ALN, Link MA, Solla DJ, Bassi E, Tierno PF, Paiva W, et al. Transfusion requirements after head trauma: a randomized feasibility controlled trial. Crit Care. 2019;23:1–10.

Knotzer H, Pajk W, Maier S, Dünser MW, Ulmer H, Schwarz B, et al. Comparison of lactated Ringer’s, gelatine and blood resuscitation on intestinal oxygen supply and mucosal tissue oxygen tension in haemorrhagic shock. Br J Anaesth. 2006;97(4):509–16.

Önen A, Çigdem MK, Deveci E, Kaya S, Turhanoǧlu S, Yaldiz M. Effects of whole blood, crystalloid, and colloid resuscitation of hemorrhagic shock on renal damage in rats: an ultrastructural study. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38(11):1642–9.

Wiles MD. Blood pressure in trauma resuscitation: “pop the clot” vs. “drain the brain”? Anaesthesia. 2017;72:1448–55.

Godoy DA, Murillo-Cabezas F, Suarez JI, Badenes R, Pelosi P, Robba C. “THE MANTLE” bundle for minimizing cerebral hypoxia in severe traumatic brain injury. Crit Care Crit Care. 2023;27:13.

Young AMH, Guilfoyle MR, Donnelly J, Smielewski P, Agarwal S, Czosnyka M, et al. Multimodality neuromonitoring in severe pediatric traumatic brain injury. Pediatr Res Pediatr Res. 2018;83:41–9.

Wiles MD. Blood pressure in trauma resuscitation: “pop the clot” vs. “drain the brain”? Anesth. 2017;72:1448–1455.

Godoy DA, Murillo-Cabezas F, Suarez JI, Badenes R, Pelosi P, Robba C. “THE MANTLE” bundle for minimizing cerebral hypoxia in severe traumatic brain injury. Crit Care. 2023;27:13.

Young AMH, Guilfoyle MR, Donnelly J, Smielewski P, Agarwal S, Czosnyka M, et al. Multimodality neuromonitoring in severe pediatric traumatic brain injury. Pediatr Res. 2018;83:41–9.

Funding

This study was funded by FAPESP (Fundação de Amparo ao Ensino e Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo), the São Paulo state research support foundation (Award Number: 2013/07832-1), and the grant recipient was Luiz Marcelo Sá Malbouisson, PhD, the last author of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made a substantial contribution to the concept and design of the study, interpreted the data, and reviewed the article. APCCB and DAO initiated the study. APCCB and LMSM performed data extraction and analyses. APCCB, LMSM, FLS, and LGCA drafted the first version of the article. LA and WP critically reviewed the article and revised it. The final manuscript was approved by all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest regarding this article.

Ethical Approval/Informed Consent

The authors confirm adherence to ethical guidelines and ethical (institutional review board) approval by CEUA (Comissão de Ética no Uso de Animais), whose purpose is to deliberate on the approval or not of research projects for studies in which the experimental protocols require animals in Brazil (approval number: CEUA/ FMUSP – 120/16).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Balzi, A.P.d.C.C., Otsuki, D.A., Andrade, L. et al. Can a Therapeutic Strategy for Hypotension Improve Cerebral Perfusion and Oxygenation in an Experimental Model of Hemorrhagic Shock and Severe Traumatic Brain Injury?. Neurocrit Care 39, 320–330 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-023-01802-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-023-01802-5