Abstract

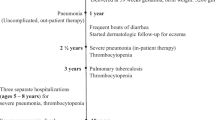

Mutations of the Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome Protein (WASP) are responsible for classic Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome (WAS), X-linked thrombocytopenia (XLT), and in rare instances congenital X-linked neutropenia (XLN). WASP is a regulator of actin polymerization in hematopoietic cells with well-defined functional domains that are involved in cell signaling and cell locomotion, immune synapse formation, and apoptosis. Mutations of WASP are located throughout the gene and either inhibit or disregulate normal WASP function. Analysis of a large patient population demonstrates a strong phenotype–genotype correlation. Classic WAS occurs when WASP is absent, XLT when mutated WASP is expressed and XLN when missense mutations occur in the Cdc42-binding site. However, because there are exceptions to this rule it is difficult to predict the long-term prognosis of a given affected boy solely based on the analysis of WASP expression.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Derry JM, Ochs HD, Francke U. Isolation of a novel gene mutated in Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome. Cell. 1994;78:635–44.

Wiskott A. Familiärer, angeborener Morbus Werihofii? Monastsschr Kinderheilkd. 1937;68:212–6.

Aldrich R, Steinberg A, Campbell D. Pedigree demonstrating a sex-linked recessive condition characterized by draining ears, eczematoid dermatits and bloody diarrhea. Pediatrics. 1954;13:133–9.

Blaese RM, Strober W, Brown RS, et al. The Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome. A disorder with a possible defect in antigen processing or recognition. Lancet. 1968;1:1056–61.

Cooper MD, Chae HP, Lowman JT, et al. Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome. An immunologic deficiency disease involving the afferent limb of immunity. Am J Med. 1968;44:499–513.

Ochs HD, Slichter SJ, Harker LA, et al. The Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome: studies of lymphocytes, granulocytes, and platelets. Blood. 1980;55:243–52.

Sullivan KE, Mullen CA, Blaese RM, et al. A multiinstitutional survey of the Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome. J Pediatr. 1994;125:876–85.

Molina IJ, Sancho J, Terhorst C, et al. T cells of patients with the Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome have a restricted defect in proliferative responses. J Immunol. 1993;151:4383–90.

Gallego MD, Santamaria M, Pena J, et al. Defective actin reorganization and polymerization of Wiskott–Aldrich T cells in response to CD3-mediated stimulation. Blood. 1997;90:3089–97.

Park JY, Shcherbina A, Rosen FS, et al. Phenotypic perturbation of B cells in the Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;139:297–305.

Westerberg L, Larsson M, Hardy SJ, et al. Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome Protein deficiency leads to reduced B-cell adhesion, migration, and homing, and a delayed humoral immune response. Blood. 2005;105:1144–52.

Westerberg LS, de la Fuente MA, Wermeling F, et al. WASP Confers selective advantage for specific hematopoietic cell populations and serves a unique role in marginal zone B cell homeostasis and function. Blood. 2008;112:4139–47.

Meyer-Bahlburg A, Becker-Herman S, Humblet-Baron S, et al. Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome Protein deficiency in B cells results in impaired peripheral homeostasis. Blood. 2008;112:4158–69.

Orange JS, Ramesh N, Remold-O’Donnell E, et al. Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome Protein is required for NK cell cytotoxicity and colocalizes with actin to NK cell-activating immunologic synapses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:11351–6.

Gismondi A, Cifaldi L, Mazza C, et al. Impaired natural and CD16-mediated NK cell cytotoxicity in patients with WAS and XLT: ability of IL-2 to correct NK cell functional defect. Blood. 2004;104:436–43.

Huang W, Ochs HD, Dupont B, et al. The Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome Protein regulates nuclear translocation of NFAT2 and NF-kappa B (RelA) independently of its role in filamentous actin polymerization and actin cytoskeletal rearrangement. J Immunol. 2005;174:2602–11.

Badolato R, Sozzani S, Malacarne F, et al. Monocytes from Wiskott–Aldrich patients display reduced chemotaxis and lack of cell polarization in response to monocyte chemoattractant protein–1 and formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine. J Immunol. 1998;161:1026–33.

Binks M, Jones GE, Brickell PM, et al. Intrinsic dendritic cell abnormalities in Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:3259–67.

de Noronha S, Hardy S, Sinclair J, et al. Impaired dendritic-cell homing in vivo in the absence of Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome Protein. Blood. 2005;105:1590–7.

Humblet-Baron S, Sather B, Anover S, et al. Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome Protein is required for regulatory T cell homeostasis. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:407–18.

Dupuis-Girod S, Medioni J, Haddad E, et al. Autoimmunity in Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome: risk factors, clinical features, and outcome in a single-center cohort of 55 patients. Pediatrics. 2003;111:622–7.

Welch MD, Mullins RD. Cellular control of actin nucleation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2002;18:247–88.

Badour K, Zhang J, Shi F, et al. The Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome Protein acts downstream of CD2 and the CD2AP and PSTPIP1 adaptors to promote formation of the immunological synapse. Immunity. 2003;18:141–54.

Sasahara Y, Rachid R, Byrne MJ, et al. Mechanism of recruitment of WASP to the immunological synapse and of its activation following TCR ligation. Mol Cell. 2002;10:1269–81.

Volkman BF, Prehoda KE, Scott JA, et al. Structure of the N-WASP EVH1 domain-WIP complex: insight into the molecular basis of Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome. Cell. 2002;111:565–76.

Hall A. Rho GTPases and the actin cytoskeleton. Science. 1998;279:509–14.

Rudolph MG, Bayer P, Abo A, et al. The Cdc42/Rac interactive binding region motif of the Wiskott Aldrich Syndrome Protein (WASP) is necessary but not sufficient for tight binding to Cdc42 and structure formation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18067–76.

Kim AS, Kakalis LT, Abdul-Manan N, et al. Autoinhibition and activation mechanisms of the Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome Protein. Nature. 2000;404:151–8.

Notarangelo LD, Mazza C, Giliani S, et al. Missense mutations of the WASP gene cause intermittent X-linked thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2002;99:2268–9.

Devriendt K, Kim AS, Mathijs G, et al. Constitutively activating mutation in WASP causes X-linked severe congenital neutropenia. Nat Genet. 2001;27:313–7.

Ancliff PJ, Blundell MP, Cory GO, et al. Two novel activating mutations in the Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome Protein result in congenital neutropenia. Blood. 2006;108:2182–9.

Moulding DA, Blundell MP, Spiller DG, et al. Unregulated actin polymerization by WASp causes defects of mitosis and cytokinesis in X-linked neutropenia. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2213–24.

Beel K, Cotter MM, Blatny J, et al. A large kindred with X-linked neutropenia with an I294T mutation of the Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome gene. Br J Haematol. 2008, Nov 1 [Epub ahead of print].

Ochs HD, Rosen FS. Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome. In: Ochs HD, Smith CIE, Puck JM, editors. Primary immunodeficiency diseases, a molecular and genetic approach. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. p. 454–69.

Jin Y, Mazza C, Christie JR, et al. Mutations of the Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome Protein (WASP): hotspots, effect on transcription, and translation and phenotype/genotype correlation. Blood. 2004;104:4010–9.

Imai K, Morio T, Zhu Y, et al. Clinical course of patients with WASP gene mutations. Blood. 2004;103:456–64.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ochs, H.D. Mutations of the Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome Protein affect protein expression and dictate the clinical phenotypes. Immunol Res 44, 84–88 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12026-008-8084-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12026-008-8084-3