Abstract

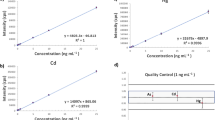

The objective of this study was to evaluate whether lead (Pb) and arsenic (As) levels in biological fluids were associated to the body composition in a group of reproductive-age women. Voluntary childbearing-age women (n = 107) were divided into three groups according to their body mass index (BMI: weight/height2 (kg/m2): low weight (BMI<18.5 kg/m2), normal \( \left( {{\text{BMI}} > 19\kern1.5pt<\kern1.5pt24.9\,{{\text{kg}} \mathord{\left/{\vphantom {{\text{kg}} {{{\text{m}}^{\text{2}}}}}} \right.} {{{\text{m}}^{\text{2}}}}}} \right) \), and overweight (BMI>25 kg/m2). Body composition and fat mass percentage were determined by the isotopic dilution method utilizing deuterated water. Blood lead concentrations were determined by graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometry and urinary arsenic (AsU) concentrations by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. The type and frequency of food consumption and lifestyle-related factors were also registered. Most women had \( {\text{PbB}}\,{\text{levels}} > 2\kern1.5pt<\kern1.5pt10\,{\mu{{\text{ g}}} \mathord{\left/{\vphantom {\mu{{\text{ g}}} {\text{dL}}}} \right.} {\text{dL}}} \), and only 2.6% had AsU concentrations above 50 μg/L. The levels of these toxic elements were not found to be associated with the fat mass percentage.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Milton A, Hasan Z, Shahidullah S, Sharmin S et al (2004) Association between nutritional status and arsenicosis due to chronic arsenic exposure in Bangladesh. Int J Environ Health Res 4:99–108

Islam L, Nabi A, Rahman M, Khan M et al (2004) Association of clinical complications with nutritional status and the prevalence of leukopenia among arsenic patients in Bangladesh. Int J Environ Res Public Health 1:74–82

Mitra S, Mazumder DN, Basu A et al (2004) Nutritional factors and susceptibility to arsenic-caused skin lesions in West Bengal, India. Environ Health Perspect 112:1104–1109

Gamble M, Liu X, Ahsan H et al (2005) Folate, homocysteine, and arsenic metabolism in arsenic-exposed individuals in Bangladesh. Environ Health Perspect 113:1683–1688

Shih R, Hu H, Weisskopf M, Schwartz B et al (2007) Cumulative lead dose and cognitive function in adults: a review of studies that measured both blood lead and bone lead. Environ Health Perspect 115:483–492

Gracia R, Snodgrass W (2007) Lead toxicity and chelation therapy. Am J Health Syst Pharm 64:45–53

WHO (2001) Environmental levels and human exposure. In: Arsenic compounds. 2nd ed. WHO, Geneva

Nordic Council of Ministers. Lead Review. WHO (2003) http://www.who.int/ifcs/documents/forums/forum5/nmr_lead.pdf

WHO (2003) Assessing the environmental burden of disease at national and local levels. In: Environmental burden of disease series, no. 2. WHO, Geneva

Wang S, Mulligan CN (2006) Occurrence of arsenic contamination in Canada: sources, behavior and distribution. Sci Total Environ 366:701–721

Menke A, Muntner P, Batuman V et al (2006) Blood lead below 0.48 micromol/L (10 microg/dL) and mortality among US adults. Circulation 114:1388–1394

Lustberg M, Silbergeld E (2002) Blood lead levels and mortality. Arch Intern Med 62:2443–2449

Rahman M, Tondel M, Ahmad S et al (1999) Hypertension and arsenic exposure in Bangladesh. Hypertension 33:74–78

Brown K, Ross G (2002) Arsenic, drinking water, and health: a position paper of the American Council on Science and Health. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 36:162–174

ATSDR (2005) Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Methods Analytical In: Arsenic; Atlanta, GA, USA. http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/csem/arsenic/biologic_fate.html

ATSDR (2007) Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Case studies in environmental medicine. In: ATSDR Publication No.: ATSDR-HE-CS-2002-2003; Atlanta, GA, USA. http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/HEC/CSEM/arsenic/cover.html#alert

DS 594/1999 (1999) Ministry of Health, Chile. Decreto Supremo Nº 594. Reglamento sobre condiciones sanitarias y ambientales. Gobierno de Chile, Ministerio de Salud

Ferruz J, Oyanguren C, Molina L (2006) Determinación de niveles de arsénico no dietario urinario en una población de trabajadores expuestos, II Región. Actualidad Científica y Técnica, Ministerio de Salud-Conicyt, pp 1-4

Lee MG, Chun OK, Song WO (2005) Determinants of the blood lead level of US women of reproductive age. J Am Coll Nutr 24:1–9

Llanos MN, Ronco AM (2009) Fetal growth restriction is related to placental levels of cadmium, lead and arsenic but not with antioxidant activities. Reprod Toxicol 188:186–191

Ronco AM, Arguello G, Munoz L et al (2005) Metals content in placentas from moderate cigarette consumers: correlation with newborn birth weight. Biometals 18:233–241

Mahaffey K (1990) Environmental lead toxicity: nutrition as a component of intervention. Environ Health Perspect 89:75–78

Burger J, Diaz-Barriga F, Marafante E et al (2003) Methodologies to examine the importance of host factors in bioavailability of metals. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 56:20–31

Barr D, Wilder L, Caudill S et al (2005) Urinary creatinine concentrations in the U.S. population: implications for urinary biologic monitoring measurements. Environ Health Perspect 113:192–200

Ellis KJ (2001) Selected body composition methods can be used in field studies. J Nutr 131:1589S–1595S

Eckhardt CL, Adair LS, Caballero B et al (2003) Estimating body fat from anthropometry and isotopic dilution: a four-country comparison. Obesity Res 11:1553–1562

Muñoz O, Bastias J, Araya M et al (2005) Estimation of the dietary intake of cadmium, lead, mercury, and arsenic by the population of Santiago (Chile) using a total diet study. Food ChemToxicol 43:1647–1655

OSHA (2003) Occupational Safety and Health Standards. Health Standards: Toxic and Hazardous Substances: Lead. CFR 307 1910.102. Occupational Safety & Health Administration; Washington, DC, USA.

Metropolitan Environmental Health Services, SESMA, Chile (2002) Caracterización de elementos inorgánicos presentes en el aire de la Región Metropolitana. Servicio de Salud Metropolitano del Ambiente-Ministerio de Salud, Santiago

CDC (2002) Managing elevated blood lead levels among young children: recommendations from the advisory committee on childhood lead poisoning prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Kosnett M, Wedeen R, Rothenberg S et al (2007) Recommendations for medical management of adult lead exposure. Environ Health Perspect 115:463–471

Navas-Acien A, Guayar E, Silbergeld E et al (2007) Lead exposure and cardiovascular disease—a systematic review. Environ Health Perspect 115:472–482

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (1998) Arsenic, inorganic; CASRN 7440-38-2. http://www.epa.gov/NCEA/iris/subst/0278.htm

Caceres D, Pino P, Montesinos N et al (2005) Exposure to inorganic arsenic in drinking water and total urinary arsenic concentration in a Chilean population. Environ Res 98:151–159

Yañez L, Ortiz D, Calderon J et al (2002) Overview of human health and chemical mixtures: problems facing developing countries. Environ Health Perspect 110(Suppl 6):901–909

Smith A, Arroyo A, Mazumder D et al (2000) Arsenic-induced skin lesions among Atacameno people in Northern Chile despite good nutrition and centuries of exposure. Environ Health Perspect 108:617–620

Gakidou E, Oza S, Vidal Fuertes C et al (2007) Improving child survival through environmental and nutritional interventions: the importance of targeting interventions toward the poor. JAMA 298:1876–1887

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the financial support of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Research Contract No. 13245/R0 and the excellent technical work of Ms. Paola Pismante.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ronco, A.M., Gutierrez, Y., Gras, N. et al. Lead and Arsenic Levels in Women with Different Body Mass Composition. Biol Trace Elem Res 136, 269–278 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-009-8546-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-009-8546-z