Abstract

An “Alternative DSM-5 Model for Personality Disorders” was published in Sect. III of DSM-5, while the identical categories and criteria from DSM-IV for the personality disorders (PDs) are in Sect. II. Given strong shifts from categorical diagnoses toward dimensional representations in psychiatry, how did the PDs end up “stuck in neutral,” with the flawed DSM-IV model perpetuated? This article reviews factors that influenced the development of the new model and data to encourage and facilitate its use by clinicians. These include recognizing 1) a dimensional structure for psychopathology for which personality may be foundational; 2) a consensus on the structure of normal and abnormal personality; 3) the clinical significance of personality; 4) PD-specific severity required to establish disorder; 5) disruption, discontinuity, and perceived clinical utility of the Alternative Model may not be problems; and 6) a way forward involving collaborative research on neurobiological and psychosocial processes, treatment planning, and outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Eaton NR et al. Contrasting prototypes and dimensions in the classification of personality pathology: evidence that dimensions, but not prototypes, are robust. Psychol Med. 2011;41:1151–63.

Haslam N, Holland E, Kuppens P. Categories versus dimensions in personality and psychopathology: a quantitative review of taxometric research. Psychol Med. 2012;42:903–20. A meta-analysis of 177 articles with a combined sample of 533,377 participants found little evidence of taxa (categories) for normal personality and mood, anxiety, eating, externalizing, and personality disorders other than schizotypal. Therefore, most variables of interest to psychiatrists and psychologists are dimensional.

Verheul R, Widiger TA. A meta-analysis of the prevalence and usage of the personality disorder not otherwise specified (PDNOS) diagnosis. J Personal Disord. 2004;18:309–19.

Grant BF et al. Co-occurrence of DSM-IV personality disorders in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Compr Psychiatry. 2005;46:1–5.

Zimmerman M, Rothchild L, Chelminski I. The prevalence of DSM-IV personality disorders in psychiatric outpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1911–8.

Widiger TA. Official classification systems. In: Livesley WJ, editor. Handbook of personality disorders. New York: Guilford; 2001. p. 60–83.

Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Gibbon M. Crossing the border into borderline personality and borderline schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1979;36:17–24.

Johansen M et al. An investigation of the prototype validity of the borderline DSM-IV construct. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;109:289–98.

Frances A. The DSM-III personality disorders section: a commentary. Am J Psychiatry. 1980;137:1050–4.

Frances A. Categorical and dimensional systems of personality diagnosis: a comparison. Compr Psychiatry. 1982;23:516–27.

Widiger TA, Trull TJ. Plate tectonics in the classification of personality disorder: shifting to a dimensional model. Am Psychol. 2007;62:71–83.

Rounsaville BJ, Alarcón RD, Andrews G, Jackson JS, Kendell RE, Kendler K. Basic nomenclature issues for DSM-V. In: Kupfer DJ, First MB, Regier DE, editors. A research agenda for DSM-V. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2002. p. 1–29.

Bernstein DP et al. Opinions of personality disorder experts regarding the DSM-IV personality disorders classification system. J Personal Disord. 2007;21:536–51.

Benjamin LS. Dimensional, categorical, or hybrid analyses of personality: a response to Widiger’s proposal. Psychol Inq. 1993;4:91–132.

Blashfield RK. Variants of categorical and dimensional models. Psychol Inq. 1993;4:95–8.

Krueger RF et al. Synthesizing dimensional and categorical approaches to personality disorders: refining the research agenda for DSM-V Axis II. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2007;16 Suppl 1:S65–73.

Helzer JE et al., editors. Dimensional approaches in diagnostic classification: refining the research agenda for DSM-V. Arlington: American Psychiatric Association; 2008.

Hyman SE. The diagnosis of mental disorders: the problem of reification. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2010;6:155–79.

Insel TR et al. Research domain criteria (RDoC): toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:748–51.

Cuthbert BN, Insel TR. Toward the future of psychiatric diagnosis: the seven pillars of RDoC. BMC Med. 2013;11:126. Article summarizes the rationale, status, and goals of the NIMH Research Domain Criteria. RDoC are translational, dimensional, measurement based; they employ novel sampling and independent (non-diagnostic) variables, integrate behavior and neuroscience, focus on constructs with solid existing evidence, and are free from fixed definitions of disorders.

Skodol AE et al. The ironic fate of the personality disorders in DSM-5. Personal Disord. 2013;4:342–9.

Kessler RC et al. The prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of twelve-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–27.

Kessler RC et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-at-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Survey initiative. World Psychiatry. 2007;6:168–76.

Kessler et al. Prevalence, persistence, and sociodemographic correlates of DSM-IV disorders in the National Cormorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:372–80.

Eaton NR et al. The structure and predictive validity of the internalizing disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 2013;122:86–92.

Krueger RF et al. Linking antisocial behavior, substance use, and personality: an integrative quantitative model of the adult externalizing spectrum. J Abnorm Psychol. 2007;116:645–66.

Krueger RF, Eaton NR. Personality traits and the classification of mental disorders: towards a more complete integration in DSM-5 and an empirical model of psychopathology. Personal Disord. 2010;1:97–118.

Keyes KM et al. Thought disorder in the meta-structure of psychopathology. Psychol Med. 2013;43:1673–83.

Skodol AE. Manifestations, assessment, and differential diagnosis. In: Oldham JM, Skodol AE, Bender DS, editors. The American psychiatric publishing textbook of personality disorders. 2nd ed. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2014. p. 131–64.

Kendler KS, Myers J. The boundaries of the internalizing and externalizing genetic spectra in men and women. Psychol Med. 2014;44:647–55.

Tackett JL et al. A unifying perspective on personality pathology across the life span: developmental considerations for the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Model of Mental Disorders. Dev Psychopathol. 2009;21:687–713.

Shiner RL, Allen TA. Seven guiding principles for assessing personality disorder in adolescents. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2013;20:361–77. Article suggests seven guiding principles for assessing PDs in adolescents: remember to assess PDs; use the DSM-5 alternative model; assess acute symptoms and underlying personality; evaluate contextual factors; gather information from adolescents and informants; focus on problematic patterns of behavior, thinking and feeling as treatment targets not diagnoses; recognize personality strengths and resources for change.

Johnson JG et al. Cumulative prevalence of PDs between adolescence and adulthood. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;118:410–3.

Feenstra DJ et al. Prevalence and comorbidity of Axis I and Axis II disorders among treatment refractory adolescents admitted for specialized psychotherapy. J Personal Disord. 2011;25:842–50.

Grilo CM et al. Frequency of PDs in two age cohorts of psychiatric inpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:140–2.

De Clercq B et al. Childhood personality pathology: dimensional stability and change. Dev Psychopathol. 2009;21:853–69.

Johnson JG et al. Age-related change in PD trait levels between early adolescence and adulthood: a community-based longitudinal investigation. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;102:265–75.

Chen H et al. Adolescent PDs and conflict with romantic partners during the transition to adulthood. J Personal Disord. 2004;18:507–25.

Crawford TN et al. Comorbid Axis I and Axis II disorders in early adolescence: outcomes 20 years later. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:641–8.

Johnson JG et al. Personality disorders in adolescence and risk of major mental disorders and suicidality during adulthood. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:805–11.

Johnson JG et al. Adolescent PDs associated with violence and criminal behavior during adolescence and early adulthood. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1406–12.

Johnson JG, Chen H, Cohen P. PD traits during adolescence and relationships with family members during the transition to adulthood. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:923–32.

Shea MT et al. Associations in the course of personality disorders and Axis I disorders over time. J Abnorm Psychol. 2004;113:499–508.

Gunderson JG et al. Major depressive disorder and borderline personality disorder revisited: longitudinal interactions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:1049–56.

Grilo CM et al. Two-year prospective naturalistic study of remission from major depressive disorder as a function of personality disorder co-morbidity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:78–85.

Grilo CM et al. Personality disorders predict relapse after remission from an episode of major depressive disorder: a six-year prospective study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:1629–35.

Skodol AE et al. Relationship of personality disorders to the course of major depressive disorder in a nationally representative sample. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:257–64.

Ansell EB et al. The association of personality disorders with the 7-year course of anxiety disorders. Psychol Med. 2011;41:1019–28.

Fenton MC et al. Psychiatric comorbidity and the persistence of drug use disorders in the United States. Addiction. 2012;107:599–609.

Hasin D et al. Relationship of personality disorders to the three-year course of alcohol, cannabis and nicotine disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:1158–67.

Low LF, Harrison F, Lackersteen SM. Does personality affect risk for dementia? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21:713–28.

Widiger TA, Simonsen E. Alternative dimensional models of personality disorder: finding a common ground. J Personal Disord. 2005;19:110–30.

Costa Jr PT, Widiger TA. Personality disorders and the five-factor model of personality. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2012.

De Fruyt F et al. General and maladaptive traits in a five-factor framework for DSM-5 in a university student sample. Assessment. 2013;20:295–307.

Fossati A et al. Reliability and validity of the Personality Inventory for DSM-5 (PID-5): predicting DSM-IV personality disorders and psychopathy in community-dwelling Italian adults. Assessment. 2013;20:689–708.

Morey LC, Krueger RF, Skodol AE. The hierarchical structure of clinician ratings of DSM-5 pathological personality traits. J Abnorm Psychol. 2013;122:836–41.

Wright AGC et al. The hierarchical structure of DSM-5 pathological personality traits. J Abnorm Psychol. 2012;121:951–7.

Gore WL, Widiger TA. The DSM-5 dimensional trait model and five-factor models of general personality. J Abnorm Psychol. 2013;122:816–21.

Thomas KM et al. The convergent structure of DSM-5 personality trait facets and Five-Factor Model trait domains. Assessment. 2013;20:308–11.

Lahey BB. Public health significance of neuroticism. Am Psychol. 2009;64:241–56.

Ozer DJ, Benet-Martinez V. Personality and the prediction of consequential outcomes. Annu Rev Psychol. 2006;57:401–21.

Ironson GH et al. Personality and HIV disease progression: role of NEO-PI-R openness, extraversion, and profiles of engagement. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:245–53.

Ciechanowski P et al. Relationship styles and mortality in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:539–44.

Cain NM et al. Interpersonal pathoplasticity in the course of major depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80:78–86.

Morey LC et al. Comparison of alternative models for personality disorders. Psychol Med. 2007;37:983–94.

Morey LC et al. Comparison of alternative models for personality disorders, II: 6-, 8- and 10-year follow-up. Psychol Med. 2012;42:1705–13. In a 10-year follow-up of patients with PDs, approaches to assessment of personality pathology that integrated normative personality traits and personality pathology were most predictive of long-term outcomes, including psychosocial functioning, chronicity of Axis I psychopathology, and medication use. DSM-IV diagnostic categories were less valid than dimensional criteria counts.

Crawford MJ et al. Classifying personality disorder according to severity. J Personal Disord. 2011;25:321–30.

Livesley WJ, Jang KL. Toward an empirically based classification of personality disorder. J Personal Disord. 2000;14:137–51.

Parker G et al. Defining personality disordered functioning. J Personal Disord. 2002;16:503–22.

Tyrer P. The problem of severity in the classification of personality disorders. J Personal Disord. 2005;19:309–14.

Hopwood CJ et al. Personality assessment in DSM-V: empirical support for rating severity, style, and traits. J Personal Disord. 2011;25:305–20.

Wakefield JC. The perils of dimensionalization: challenges in distinguishing negative traits from personality disorders. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2008;31:379–93.

Bender DS, Morey LC, Skodol AE. Toward a model for assessing level of personality functioning in DSM-5, part I: a review of theory and methods. J Pers Assess. 2011;93:332–46.

Morey LC et al. Toward a model for assessing level of personality functioning in DSM-5, part II: empirical articulation of a core dimension of personality pathology. J Pers Assess. 2011;93:347–53.

Morey LC, Bender DS, Skodol AE. Validating the proposed DSM-5 severity indicator for personality disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2013;201:729–35. Data from a national sample of 337 clinicians indicated that The Level of Personality Functioning Scale in DSM-5 Section III was substantially correlated with other measures of personality pathology and with clinical judgments of psychosocial functioning, risk of violence or self-harm, prognosis, and optimal treatment intensity. A “moderate” or greater rating of impairment in personality functioning identified patients who met criteria for a DSM-IV PD with high sensitivity and specificity, confirming that the single-item LPFS can identify personality disorders efficiently and effectively.

Skodol AE. Personality disorders in DSM-5. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2012;8:317–44.

Clarkin JF, Huprich SK. Do DSM-5 personality disorder proposals meet criteria for clinical utility? J Personal Disord. 2011;25:192–205.

Luyten P, Blatt SJ. Integrating theory-driven and empirically-derived models of personality development and psychopathology: a proposal for DSM V. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31:52–68.

Luyten P, Blatt SJ. Interpersonal relatedness and self-definition in normal and disrupted personality development: retrospect and prospect. Am Psychol. 2013;68:172–83.

Pincus AL. Some comments on nomology, diagnostic process, and narcissistic personality disorder in the DSM-5 proposal for personality and personality disorders. Personal Disord. 2011;2:41–53.

Skodol AE, Bender DS, Oldham JM. An alternative model for personality disorders: DSM-5 section III and beyond. In: Oldham JM, Skodol AE, Bender DS, editors. The American psychiatric publishing textbook of personality disorders. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2014. p. 511–44.

Ro E, Clark LA. Psychosocial functioning in the context of diagnosis: assessment and theoretical issues. Psychol Assess. 2009;21:313–24.

Sanislow CA et al. Developing constructs for psychopathology research: research domain criteria. J Abnorm Psychol. 2010;119:631–9.

Stanley B, Siever LJ. The interpersonal dimension of borderline personality disorder: toward a neuropeptide model. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:24–39.

Donaldson ZR, Young LJ. Oxytocin, vasopressin, and the neurogenetics of sociality. Science. 2008;322:900–4.

Fair DA et al. The maturing architecture of the brain’s default network. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105:4028–32.

Northoff G et al. Self-referential processing in our brain – a meta-analysis of imaging studies on the self. Neuroimage. 2006;31:440–57.

Preston SD et al. The neural substrates of cognitive empathy. Soc Neurosci. 2007;2:254–75.

Qin P, Northoff G. How is our self related to midline regions and the default-mode network? Neuroimage. 2011;57:1221–33.

Gunderson JG. Seeking clarity for future revisions of the personality disorders in DSM-5. Personal Disord. 2013;4:368–76.

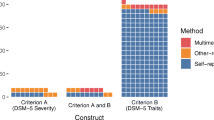

Morey LC, Skodol AE. Convergence between DSM-IV and DSM-5 diagnostic models for personality disorder: evaluation of strategies for establishing diagnostic thresholds. J Psychiatr Pract. 2013;19:179–93.

Morey LC. Personality disorders under DSM-III and DSM-III-R: an examination of convergence, coverage, and internal consistency. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145:573–7.

Regier DA et al. DSM-5 field trials in the United States and Canada, part II: test-retest reliability of selected categorical diagnoses. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:59–70.

Zimmerman J et al. Assessing DSM-5 level of personality functioning from videotaped clinical interviews: a pilot study with untrained and clinically inexperienced students. J Pers Assess. 2014. doi:10.1080/00223891.2013.852563.

Moscicki EK et al. Testing DSM-5 in routine clinical practice settings: feasibility and clinical utility. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64:952–60.

Morey LC, Skodol AE, Oldham JM. Clinician judgments of clinical utility: a comparison of DSM-IV-TR personality disorders and the alternative model for DSM-5 personality disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 2014;123:398–405. In a national sample of 337 clinicians who rated patients with both DSM-IV-TR criteria (now DSM-5 Section II) and the DSM-5 alternative model for PDs, DSM-IV-TR was seen as easy to use and useful for professional communication. In all other respects, including communication with patients, comprehensiveness, descriptiveness, and utility for treatment planning, the DSM-5 Section III model (especially the dimensional trait model) was seen as equally or more useful than DSM-IV-TR. These views were held regardless of whether the clinician was a psychiatrist or a psychologist.

First MB, Bell CC, Cuthbert B, Krystal JH, Malison R, Offord DR, et al. Personality disorders and relational disorders. In: Kupfer DJ, First MB, Regier DA, editors. A research agenda for DSM-V. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2002. p. 123–99.

Shiner RL, Masten AS. Childhood personality as a harbinger of competence and resilience in adulthood. Dev Psychopathol. 2012;24:507–28.

Skodol AE et al. Positive childhood experiences: resilience and recovery from PD in early adulthood. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1102–8.

Skodol AE. The resilient personality. In: Reich JW, Zautra AJ, Hall JS, editors. Handbook of adult resilience. New York: Guilford Press; 2010. p. 112–25.

Krueger RF, Markon KE. The role of the DSM-5 personality trait model in moving toward a quantitative and empirically based approach to classifying personality and psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2014;10:477–501. Article reviews research to date on the DSM-5 personality trait model. Studies to date suggest reasonable coverage of personality pathology, but also areas for continued improvement.

Krueger RF et al. DSM-5 and the path toward empirically based and clinically useful conceptualization of personality and psychopathology. Clin Psychol Sci Prac. 2014. In press.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Andrew E. Skodol has received expert testimony fees from Lazarus & Associates. Dr. Skodol has received honorarium from Penn State University, Brigham Young University, Global Medical Education, Arizona Psychiatric Society, St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital, Norwegian Psychiatric Association. Wright State University, World Psychiatric Association, and the American Psychiatry Association. He has also received royalties from American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc., and UpToDate. Dr. Skodol has also receive paid travel accommodations from Penn State University, Brigham Young University, St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital, Norwegian Psychiatric Association, Wright State University, World Psychiatric Association, and the American Psychiatric Association.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Psychiatric Diagnosis

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Skodol, A.E. Personality Disorder Classification: Stuck in Neutral, How to Move Forward?. Curr Psychiatry Rep 16, 480 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-014-0480-x

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-014-0480-x

Keywords

- Personality disorders

- DSM-5

- Alternative model

- Diagnosis

- Classification

- Personality functioning

- Level of personality functioning scale

- Personality traits

- General criteria for personality disorder

- Antisocial personality disorder

- Avoidant personality disorder

- Borderline personality disorder

- Narcissistic personality disorder

- Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder

- Schizotypal personality disorder

- Negative affectivity

- Detachment

- Antagonism

- Disinhibition

- Psychoticism

- Five-factor model

- Research domain criteria

- Reliability

- Clinical utility

- Predictive validity

- Adaptive traits