Abstract

The delivery of brief interventions (BIs) in health care settings to reduce problematic alcohol consumption is a key preventive strategy for public health. However, evidence of effectiveness beyond primary care is inconsistent. Patient populations and intervention components are heterogeneous. Also, evidence for successful implementation strategies is limited. In this article, recent literature is reviewed covering BI effectiveness for patient populations and subgroups, and design and implementation of BIs. Support is evident for short-term effectiveness in hospital settings, but long-term effects may be confounded by changes in control groups. Limited evidence suggests effectiveness with young patients not admitted as a consequence of alcohol, dependent patients, and binge drinkers. Influential BI components include high-quality change plans and provider characteristics. Health professionals endorse BI and feel confident in delivering it, but training and support initiatives continue to show no significant effects on uptake, prompting calls for systematic approaches to implementing BI in health care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Alcohol use has been identified by the World Health Organization as the second greatest risk to public health in developed countries [1]. Screening and brief intervention (SBI) is established as an effective preventive approach to reduce hazardous or harmful drinking, particularly in primary care settings [2]. Brief interventions (BIs) may involve 1 to 5 sessions of 5 to 60 min of structured information and advice giving, or counseling based on approaches such as motivational interviewing (MI) [3], wherein patients’ own motivations are empathetically explored and guided toward change [4]. SBI is widely recommended in public health policies as preventive practice to reduce problem drinking. In the United Kingdom, for example, SBI is endorsed in the national guidelines for treatment of alcohol-related risk and harm [5], and its implementation is central to the government’s preventive strategy for public health [6]. In the United States, SBI with referral to treatment (SBIRT) for the identification and treatment of hazardous alcohol use is recommended in primary care by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Hospital emergency departments (EDs) provide a valuable opportunity to treat risky drinking in which patients with relatively high rates of hazardous to dependent drinking present in relation to a recent medical event [7]. Routine SBI for alcohol in EDs is promoted by the American College of Emergency Physicians [8] and also mandated in trauma wards by the American College of Surgeons [9–11].

While improving the treatment of unhealthy drinking in all health care settings is an important goal, some issues persist. Where effectiveness has been shown, it is still not clear how persistent those effects may be [12]. Modal follow-up time is 1 year, and the number of studies with longer follow-up is small. There is debate as to how far evidence for the effectiveness of SBI in primary care can be extrapolated to other populations and settings [13–17]. Existing evidence for the effectiveness of BIs for alcohol use across hospital sites of emergency, inpatient, and trauma care has been mixed, and drawing overall conclusions is difficult given the distinct characteristics of different hospital departments and different characteristics of patients across these settings [18]. The considerable variation in the scale, approach, and content of BIs means that there is a need to clarify and delineate their essential and effective components [18, 19, 20•, 21]. In addition, it is important to establish the minimum necessary components of effective BI in routine practice, where there may be therapeutic drift from BI protocol [22]. A further key issue is to understand in which contexts or with which populations different models of BI may be most effective. Moreover, uptake of BI by professionals in various health care settings continues to fall short of expected levels.

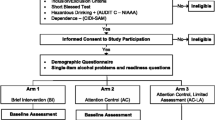

To assess how current research is addressing these issues, recent evidence is reviewed here for the effectiveness of BI in health care settings beyond primary care, how efficacy may vary according to characteristics of subgroups within patient populations and the design of BIs, and improving the implementation of BIs in primary and other health care settings. A search was conducted for recently published research relating to BIs in nonspecialist health care settings to moderate alcohol consumption in hazardous or moderately dependent drinkers (Fig. 1). Findings are discussed in relation to the areas of interest identified above.

Effectiveness Across Health Care Settings

The effectiveness of alcohol BIs within primary care was further confirmed by a recent major randomized controlled trial (RCT) in 5 college health clinics screening 12,900 students, 986 of whom were eligible and took part in the study [23]. At 12 months, those receiving two 5-min, MI-based counseling visits from general practitioners (GPs) and two follow-up calls had reduced their previous month’s consumption by a mean of 27.2%, which was significantly more than the 21% reduction among the control group. Another RCT in primary care in Thailand found effects of a three-session MI intervention from nurses at 3 and 6 months on drinks per day and frequency of hazardous and binge drinking [24]. Also, two RCTs investigated the effects of BI in primary care on the underresearched group of at-risk drinkers older than 54 years of age. One trial randomly assigned 631 individuals to receive a control booklet or a multifaceted BI [25]. The other followed up 222 older at-risk drinkers who had received a repeated telephone intervention or control [26]. The trials found short-term effects of these interventions on whether individuals were drinking riskily, the number of drinks they reported consuming, and the rates of heavy drinking, but only the effect on number of drinks in the former trial remained significant at 12 months.

Recent reviews of studies of BIs in hospital settings, while emphasizing their potential as sites for opportunistic SBI, note a lack of consistency in findings [18]. A review of trials of BIs targeting patients with comorbid substance use and mental or physical health problems found studies in a range of health care settings that reported effectiveness in terms of alcohol outcomes [27]. Two of the six trials for comorbid mental health compared MI with education or informational controls and found positive outcomes at 6 months with regard to frequency or volume of drinking. Another found no significant differences in drinking behaviors between groups following a cognitive-behavioral therapy–based intervention, while two trials for patients with comorbid physical conditions found significant reductions in alcohol use at 12 months following interventions providing brief advice.

More recent studies on adult patients in other health care settings offer some evidence for short-term effectiveness. A quasi-experimental trial of SBIRT in the United States recruited 1,132 patients from 14 ED sites, with 433 patients included at final follow-up, and found significant differences at 3 months in typical number of drinks per week and maximum number of drinks per occasion [28]. A BI based on MI also predicted abstinence maintained at 3 months among 50 harmful drinking patients admitted to a Danish hospital for alcohol treatment [29]. Two studies in Poland and Switzerland randomly assigned ED patients screening positively for at-risk to dependent drinking (n = 446 and n = 987, respectively) to screening-only, assessment, or BI conditions and found reductions over time within groups in at-risk drinking, drinks per day, and drinking days per week. [30, 31]. In a Swedish study, 158 transport company employees who had screened positively for hazardous/harmful drinking in occupational health and lifestyle checks were randomly assigned to receive BI, comprehensive intervention, or a control [32]. None of these five studies found significant differences between intervention and control groups in the outcomes stated at 12 months despite some significant reductions in consumption within groups. However, another RCT in medical/surgical wards in Taiwan recruited 308 male patients who reported consuming more than 14 standard drinks per week [33]. Those receiving an MI-based BI with booster sessions were found to be drinking significantly less on significantly fewer days per week with significantly fewer days of heavy drinking per week at 4-, 9-, and 12-month follow-ups.

Apart from the last study, results from these hospital and occupational health settings seem to indicate only a short-term effect of BI on the consumption of alcohol compared with studies in primary care. Nevertheless, there were significant reductions in consumption within groups including controls, and this may indicate a bias toward the null [18]. Assessment reactivity and regression to the mean have been highlighted as likely confounding factors contributing to results such as these [32, 34]. However, in two of the above studies, the authors did not attribute their results to assessment reactivity, because change was observed in the screened as well as in the assessed control groups [30, 31]. Bernstein et al. [28] attributed their lack of significant effect at 12 months to a combination of high attrition and a single-contact intervention. Effect sizes for control group change in trials of SBI for alcohol were found in a previous review to be extremely heterogeneous, precluding estimation of an overall effect, and to an extent that cannot be entirely accounted for by assessment reactivity or regression to the mean [35]. Nevertheless, a more recent systematic review of control group change in 16 trials of BI for alcohol use with more than 30 control group participants indicated a mean consumption change of −0.37 in control groups, and a mean effect size change of 0.37 [20•]. In 54% of those studies, advice or referral was handed out to control group participants, and the assessments used varied widely. The authors suggested various measures that may allow future research to isolate more clearly the effects of intervention itself: enhancing diversity, blinding participants, simplifying assessments, and using analytic techniques to limit the impact of outliers and regression to the mean.

Even if the long-term effects on a primary outcome of alcohol consumption are not apparent, effects on secondary outcomes may be important. For instance, a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of SBI on usage of hospital resources found a nonsignificant reduction in usage of ED services associated with BI, although the limitations of data available to the study were stressed [36]. In a US study, 3,338 14- to 18-year-olds admitted to an ED were screened for alcohol use and violence in the past year. A total of 726 who scored positively participated in a trial of a therapist-delivered BI for both violence and alcohol based on MI and skills training [37]. At 6 months, the intervention was associated with significantly fewer reports of alcohol consequences than a 3-min computer intervention or delivery of a brochure in the control condition.

Effects for Particular Groups or Characteristics

An intervention that does not show a significant effect on a population as a whole might still be more effective with some individuals than with others, and several studies have examined interactions between intervention effects and other factors. In an RCT in the United States, 172 ED patients 18 to 24 years of age received an MI intervention or feedback alone [38]. At 12 months, alcohol use was significantly reduced in the intervention condition only for particular subgroups: those who were at-risk drinkers but had not drank before the medical event that brought them to hospital, those attributing their medical event to alcohol to a low to moderate extent, and those reporting low to medium readiness to change their drinking. The authors concluded that MI is a more effective model than advice giving among young, heavy-drinking patients who do not believe that their drinking has bought them to hospital. Those admitted as an acknowledged consequence of alcohol consumption may have already been motivated by their accident to an extent that either model is as effective. However, results may reflect geographic characteristics. Replication of these findings in further and older populations could help communicate the wider potential for SBI to ED staff providers, who may view it as an intervention for those admitted with manifest consequences of alcohol problems. Furthermore, individuals who had self-inflicted injuries or who were in police custody, for whom the intervention may have been less effective, were excluded. A BI trial in the United Kingdom with 103 ED patients who had deliberately self-harmed found no significant reduction in their units consumed per drinking day at 3 or 6 months [39].

In Spain, the efficacy of a physician-delivered BI was tested with 752 individuals who scored positively for binge drinking (5+/4+ standard drinks on any one occasion) from among 15,325 screened in primary health care settings [40]. Significantly greater reductions persisted at 12 months in the intervention group compared with the control group with regard to how many participants binged and how often, number of drinking episodes, and weekly number of drinks. Comparing this with findings from studies of hazardous drinkers in general suggests that BI effects may be more sustained for binge drinkers than for excessive drinkers consuming lower daily amounts.

Severity of alcohol problems may also be a factor in BI effectiveness. A systematic review of BIs in primary care prompted by concern that screening does not usually distinguish between heavy drinkers and dependents found no support for the efficacy of BI among dependent drinkers [16]. Among the 16 RCTs included, only 2 studies—neither of which had shown efficacy—had retained heavy or dependent drinkers in their samples. However, a recent RCT in Texas in which 1,336 ED patients were screened for dependence indicated significant interactions between the effects of brief MI and dependence on alcohol [41••]. At 12-month follow-up, dependent drinkers who received the intervention were consuming a significantly lower volume per week at a lower maximum amount per day, with more days abstinent than those who received treatment as usual. There were no significant differences between conditions among nondependent drinkers, and their volume consumed per week and days abstinent had increased at follow-up. These results inform the findings of efficacy in a hospital setting from Liu and colleagues [33] above. A total of 49% of their sample had a diagnosis of dependence and were more likely than other participants to participate at all three stages of the trial. A separate analysis of this dependent subgroup showed significant effects of BI on alcohol outcomes at 12 months.

If those drinking at dependent levels are affected by BIs as these two studies indicate, then this may be of benefit not just in reducing their drinking but in encouraging them to seek additional treatment. For instance, Liu et al. [33] noted that among their intervention group, the more intervention sessions attended, the more likely the participant was to seek further treatment. In a study of ED patients with substance use disorders (including alcohol), 2,493 who were screened and received BI were significantly more likely than a matched unscreened comparison group of 2,493 to register for treatment for dependence [42]. A total of 1,365 of those who received a BI had scored positively for harmful to dependent drinking and were referred for 4 to 12 sessions of MI aimed at enhancing the individual’s efforts to reduce his or her substance use. The 265 who went on to receive this “brief treatment” were significantly more likely again to register for dependence treatment than those who did not receive brief treatment. These findings argue against excluding dependent drinkers from trials of BI, and there may be wider exclusions that should be reconsidered. For instance, a review of studies on the effectiveness of BIs for alcohol use among traumatic brain injury patients concluded that they are systematically excluded from trials, without conclusive evidence that those drinking riskily would not benefit from intervention [43].

Effective Models of Brief Interventions

If assessment or screening reactivity means that trials continue to find no significant effect of a longer intervention as opposed to a shorter one, brevity may be considered a key characteristic of BI. A critical review of 12 SBI trials in college health services with before and after data concluded that the 6 controlled studies showing a significant reduction in alcohol consumption indicate that time-limited (<75 min), single-session interventions with MI and feedback components are effective, although only 3 of these followed up at 12 months [21]. In a qualitative study, 17 physicians perceived the discussion and delineation of drinking and the agreement of life goals and strategies for reduction as the most practical and effective components of BI for alcohol [44]. This suggests that these components are likely to achieve the best uptake by clinical staff. Another study tested components of a BI (40–60 min of MI, with booster sessions in only one intervention group 7–10 days after discharge) with 333 hazardous injured drinkers in the hospital [45]. It was determined that a combination of high patient readiness to change and the formation of a change plan of high quality (as coded by two independent raters) yielded better than predicted outcomes, more so than either aspect on its own.

Other work has highlighted the salience of provider characteristics. Analysis of data from an RCT in US trauma centers indicated an interaction between BI effects and ethnic matching such that reductions in frequency of heavy drinking, maximum amount consumed in a day, and volume per week were all significantly greater if the patient and provider shared the same ethnicity [46]. This reflects the explanation offered by Daeppen and colleagues [31] for nonsignificant results in their RCT of a BI. Drawing on the process research elements of the study, they found that differences in counselor performance were influential despite systematic MI training, that counselors who had better MI skills achieved better results, and that patients with better communication skills achieved better outcomes. The authors argue for greater attention to provider characteristics relative to design components when evaluating BIs.

However, this may only be relevant when the model of BI draws on MI, rather than information and advice giving, and when BI is delivered in person. Not all BI models involve face-to-face encounters. For instance, a study of SBI delivered by phone with interactive voice technology at a primary care center identified similar proportions of patients as responding positively to paper methods, and indicated a 24% reduction in alcohol consumed after 2 weeks [47, 48]. Computerized BI has been found to be effective [49]. A systematic review of 24 studies of online BI found that this mode of treatment could reduce amounts of alcohol consumed by adults and reduce binge drinking among students, although the measures of central tendency used in many studies did not account for the skewed data [50]. The effect size was greater in nonstudent populations and significant in all but a few of the studies identified. In Sweden, a computer-based BI was tested in a hospital ED [51]. A total of 41% of 3,848 admissions were directed by nurses to complete a screening instrument themselves and to receive long or short tailored feedback via a dedicated computer. Of these, 1,570 (39% aged 18–29 years) completed the screening and received the feedback, indicating the acceptability and reach of this format [52]. A total of 93 patients completed a questionnaire at 6 months, although heavy episodic drinkers tended not to consent to follow-up. Their weekly consumption was significantly reduced, but without significant differences between the conditions. Frequency of heavy episodic drinking, however, was significantly lowered among those receiving longer feedback.

Implementation of Brief Interventions in Health Care Settings

Even if interventions are proven effective, they may nevertheless provide no benefit to patients unless they are routinely delivered. Practitioner uptake of BI in health care is still limited. For instance, only 11% of US EDs routinely screen for alcohol, and staff feel they lack the time and resources for this work [8]. Qualitative studies and surveys of provider opinion have explored issues concerning the implementation of SBI in health care settings [53–58]. This work largely paints a familiar picture, albeit extending knowledge to countries such as Slovenia and Thailand: providers endorse the interventions and believe they could deliver them but do not have the support or opportunity to do so. In England, GPs express more commitment to preventive practice for alcohol use than they did 10 years ago and feel more prepared and able to enact this, yet still fall short of expectations for the delivery of SBI [59]. It was found that physicians in Korean EDs tend to judge the risk of patients’ drinking against their own consumption [53], similar to previous findings on GPs in the United Kingdom [60].

It is typically concluded in these reports that a need exists for further practitioner training and support. However, small or nonsignificant effects continue to be found for initiatives to boost preventive practice with regard to alcohol. A cluster RCT of dissemination strategies carried out with 112 German practices found that an online quality improvement program for treatment of alcohol use disorders that included discussions with staff did not significantly affect practitioner performance [61]. An electronic reminder for practitioners in a US Veterans clinic to follow up positive screenings did not significantly affect rates of BI observed [62]. Finally, an intensive program of training, booster sessions, personalized and handwritten reminders, incentives, and feedback for 31 physicians at 4 US outpatient clinics resulted in referral to BI of only 39% of patients screened as eligible, although variation across 4 clinics was between 17% and 51% [63]. Another reason why recent findings from implementation studies may seem to offer little new insight is the difficulty of sustaining evaluative research over the long term. In the latter study, it was noted that rates of referral to BI increased from 34% to 47% in the second year, and the authors speculated that their intervention may have a cumulative effect of change on professional culture over several years [63].

In a focus group study of the views of 40 GPs from Norway [64] that followed up on issues raised in a survey [65], GPs were found to identify social and structural barriers to implementing SBI, including difficulty accommodating SBI within normal routines, orientation toward treatment rather than prevention, and concern about patient relationships. Training on how to deliver SBI or encouragement to do so may be unlikely to overcome these issues unless programs take account of such concerns (eg, by signposting evidence that patients are broadly positive about lifestyle questions if they appear relevant to their own health and are asked in the proper way). Rather than simply training one group of practitioners, systematic, large-scale approaches aimed at professional, organizational, and social levels may do more to transform attitudes regarding alcohol and treatment behaviors (eg, by facilitating discussion of health risks between GPs and patients) [22, 57, 64, 66–68].

The Swedish Risk Drinking Project is important in this respect [69•]. Its objective was to encourage health care professionals in four arenas (primary care, child health care, maternity care, and occupational health) to ask their patients about alcohol use and offer brief, structured advice. Adopted as a central plank of national health policy and with evaluative data gathered at baseline and 3-year follow-up, it has provided a uniquely broad and long-term view of how SBI can be instituted in health care contexts and at a population level. At follow-up, substantially more participating practitioners in all arenas reported feeling very knowledgeable about helping patients reduce hazardous alcohol consumption. The proportion of primary and occupational health staff feeling more effective and always or often talking to their patients about alcohol had increased from baseline to follow-up. The authors attributed these gains explicitly to the broad scope of the endeavor. For instance, all staff at health care institutions were trained, and the concepts of hazardous drinking and preventive approaches were widely “marketed.” The cross-sectional data limit what can be concluded about causality, and the statistical significance of results is not specified in the study report. The authors relied on self-report rather than more objective measures of outcome, and response rates varied across professions, between 43% and 80%. Nevertheless, the scale of the project is exemplary and means that other research findings from the evaluation will be of great interest.

Conclusions

Trials of the effectiveness of SBI against problem drinking have continued to build on established effectiveness in primary care. However, they continue to reach inconclusive results in hospitals and offer little evidence of long-term effects in this setting. Changes in alcohol outcomes over time are frequently found in control and intervention groups, and wider uptake of the suggestions offered by Bernstein et al. [20•] may tackle the crucial issues of assessment reactivity and control group change for the field. Studies of mediating variables and subpopulations among hospital patients show promising results; in particular, they suggest a need to revise the prevailing wisdom that BIs are only effective for hazardous to harmful rather than dependent drinkers, or less effective with dependent drinkers. Moving toward specific and testable models or a more detailed understanding of which components yield which effects would lead to greater clarity regarding where and how BIs for alcohol are effective. More rigorous and detailed qualitative work would be helpful in this, particularly in explaining how provider characteristics—or the absence of a provider in person—influence interventions. It would be useful to clarify the role of MI components against information and advice-giving delivery models. Finally, recent research into the implementation of BIs against problem drinking in health care settings suggests that translational work among researchers, GPs, and others to enhance practical applications of SBI and identify broader strategies and outcomes would boost the uptake of this important treatment.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:• Of importance •• Of major importance

World Health Organization: Global Health Risks. WHO: Geneva; 2009.

Kaner E, Beyer F, Dickinson H, et al. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007;CD004148.

Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change. New York: Guilford; 2002.

Heather N. Developing, evaluating and implementing alcohol brief interventions in europe. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2011;30:138–47.

Kaner E. Nice work if you can get it: development of national guidance incorporating screening and brief intervention to prevent hazardous and harmful drinking in England. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29:589–95.

Lavoie D. Alcohol identification and brief advice in England: a major plank in alcohol harm reduction policy. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29:608–11.

Blow FC, Walton MA, Murray R, et al. Intervention attendance among emergency department patients with alcohol- and drug-use disorders. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71:713–9.

Cunningham RM, Harrison SR, McKay MP, et al. National survey of emergency department alcohol screening and intervention practices. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55:556–62.

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism: Helping patients who drink too much: A Clinician’s guide. US Department of Health & Human Services: Rockville, MD; 2005.

Charbonney E, McFarlan A, Haas B, et al. Alcohol, drugs and trauma: consequences, screening and intervention in 2009. Trauma. 2010;12:5–12.

Robinson RL. The advanced practice nurse role in instituting screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment program at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. J Trauma Nurs. 2010;17:74–9.

Jepson RG, Harris FM, Platt S, Tannahill C. The effectiveness of interventions to change six health behaviours: a review of reviews. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:538.

Madras BK. Candidate performance measures for screening for, assessing, and treating unhealthy substance use in hospitals. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:72–3.

Nilsen P, Kaner E, Babor TF. Brief intervention, three decades on: an overview of research findings and strategies for more widespread implementation. Nordic Studies Alcohol Drugs. 2008;25:453–67.

Bischof G, Reinhardt S, Freyer-Adam J, et al. Severity of unhealthy alcohol consumption in medical inpatients and the general population: is the general hospital a suitable place for brief interventions? Int J Public Health. 2010;55:637–43.

Saitz R. Alcohol screening and brief intervention in primary care: absence of evidence for efficacy in people with dependence or very heavy drinking. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29:631–40.

Saitz R. Candidate performance measures for screening for, assessing, and treating unhealthy substance use in hospitals: advocacy or evidence-based practice? Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:40–3.

Field CA, Baird J, Saitz R, et al. The mixed evidence for brief intervention in emergency departments, trauma care centers, and inpatient hospital settings: what should we do? Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:2004–10.

Michie S, Abraham C, Eccles M, et al. Strengthening evaluation and implementation by specifying components of behaviour change interventions: a study protocol. Implement Sci. 2011;6:10.

• Bernstein JA, Bernstein E, and Heeren TC: Mechanisms of change in control group drinking in clinical trials of brief alcohol intervention: implications for bias toward the null. Drug and Alcohol Rev. 2010;29:498–507. This is a systematic review on the key issue of control group change, with recommendations for addressing this in future research.

Seigers DKL, Carey KB. Screening and brief interventions for alcohol use in college health centers: a review. J Am Coll Health. 2010;59:151–8.

McCormick R, Docherty B, Segura L, et al. The research translation problem: alcohol screening and brief intervention in primary care: real world evidence supports theory. Drugs Educ Prev Policy. 2010;17:732–48.

Fleming MF, Balousek SL, Grossberg PM, et al. Brief physician advice for heavy drinking college students: a randomized controlled trial in college health clinics. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71:23–31.

Noknoy S, Rangsin R, Saengcharnchai P, et al. RCT of effectiveness of motivational enhancement therapy delivered by nurses for hazardous drinkers in primary care units in Thailand. Alcohol Alcohol. 2010;45:263–70.

Moore AA, Blow FC, Hoffing M, et al. Primary care-based intervention to reduce at-risk drinking in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2010;106:111–20.

Lin JC, Karno MP, Tang LQ, et al. Do health educator telephone calls reduce at-risk drinking among older adults in primary care? J Gen Intern Med. 2011;25:334–9.

Kaner E, Brown N, Jackson K. A systematic review of the impact of brief interventions on sustance use and co-morbid physical and mental health conditions. Ment Health Susbt Use 2011;4:38–61.

Bernstein E, Bernstein J, Feldman J, et al. The impact of screening, brief intervention and referral for treatment in emergency department patients’ alcohol use: a 3-, 6-and 12-month follow-up. Alcohol Alcohol. 2010;45:514–9.

Bager P, Vilstrup H. Post-discharge brief intervention increases the frequency of alcohol abstinence—a randomized trial. J Addict Nurs. 2010;21:37–41.

Cherpitel CJ, Korcha RA, Moskalewicz J, et al. Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT): 12-month outcomes of a randomized controlled clinical trial in a Polish emergency department. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:1922–8.

Daeppen JB, Bertholet N, Gaume J. What process research tells us about brief intervention efficacy. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29:612–6.

Hermansson U, Helander A, Brandt L, et al. Screening and brief intervention for risky alcohol consumption in the workplace: results of a 1-year randomized controlled study. Alcohol Alcohol. 2010;45:252–7.

Liu S-I, Wu S-I, Chen S-C, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a brief intervention for unhealthy alcohol use in hospitalized Taiwanese men. Addiction. 2011;106:928–40.

McCambridge JIM. Research assessments: instruments of bias and brief interventions of the future? Addiction. 2009;104:1311–2.

Jenkins RJ, McAlaney J, McCambridge J. Change over time in alcohol consumption in control groups in brief intervention studies: systematic review and meta-regression study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;100:107–14.

Bray JW, Cowell AJ, Hinde JM. A systematic review and meta-analysis of health care utilization outcomes in alcohol screening and brief intervention trials. Medical Care. 2011;49:287–94.

Walton MA, Chermack ST, Shope JT, et al. Effects of a brief intervention for reducing violence and alcohol misuse among adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304:527–35.

Barnett NP, Apodaca TR, Magill M, et al. Moderators and mediators of two brief interventions for alcohol in the emergency department. Addiction. 2010;105:452–65.

Crawford MJ, Csipke E, Brown A, et al. The effect of referral for brief intervention for alcohol misuse on repetition of deliberate self-harm: an exploratory randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med. 40:1821–28.

Rubio G, Jimenez-Arriero MA, Martinez I, et al. Efficacy of physician-delivered brief counseling intervention for binge drinkers. Am J Med. 2010;123:72–8.

•• Field CA and Caetano R: The effectiveness of brief intervention among injured patients with alcohol dependence: who benefits from brief interventions? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;111:13–20. This was a robust large-scale study countering prevailing opinion regarding the efficacy of BIs for dependent drinkers.

Krupski A, Sears JM, Joesch JM, et al. Impact of brief interventions and brief treatment on admissions to chemical dependency treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;110:126–36.

Corrigan JD, Bogner J, Hungerford DW, Schomer K. Screening and brief intervention for substance misuse among patients with traumatic brain injury. J Trauma. 2010;69:722–6.

Grossberg P, Halperin A, Mackenzie S, et al. Inside the physician’s black bag: critical ingredients of brief alcohol interventions. Subst Abus. 2010;31:240–50.

Lee CS, Baird J, Longabaugh R, et al. Change plan as an active ingredient of brief motivational interventions for reducing negative consequences of drinking in hazardous drinking emergency-department patients. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71:726–33.

Field C, Caetano R. The role of ethnic matching between patient and provider on the effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions with Hispanics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:262–71.

Rose GL, MacLean CD, Skelly J, et al. Interactive voice response technology can deliver alcohol screening and brief intervention in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:340–4.

Rose GL, Skelly JM, Badger GJ, et al. Automated screening for at-risk drinking in a primary care office using interactive voice response. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71:734–8.

Carroll K, Rounsaville B. Computer-assisted therapy in psychiatry: Be brave—it’s a new world. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12:426–32.

Khadjesari Z, Murray E, Hewitt C, et al. Can stand-alone computer-based interventions reduce alcohol consumption? A systematic review. Addiction. 2011;106:267–82.

Trinks A, Festin K, Bendtsen P, Nilsen P. Reach and effectiveness of a computer-based alcohol intervention in a swedish emergency room. Int Emerg Nurs. 2010;18:138–46.

Vaca F, Winn D, Anderson C, et al. Feasibility of emergency department bilingual computerized alcohol screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment. Subst Abus. 2010;31:264–9.

Jeon B, Noh H, Kim C, et al. Does the drinking behavior of interns and residents affect their attitudes toward the screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment (SBIRT) regarding alcohol? Journal of the Korean Society of Emergency Medicine. 2010;21:495–503.

Amaral MB, Ronzani TM, Souza-Formigoni MLO. Process evaluation of the implementation of a screening and brief intervention program for alcohol risk in primary health care: an experience in Brazil. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29:162–8.

Groves P, Pick S, Davis P, et al. Routine alcohol screening and brief interventions in general hospital in-patient wards: acceptability and barriers. Drug-Educ Prev Policy. 2010;17:55–71.

Shepherd S, Young L, Clarkson JE, et al. General dental practitioner views on providing alcohol related health advice; an exploratory study. Br Dent J. 2010;208.

Susic TP, Kersnik J, Kolsek M. Why do general practitioners not screen and intervene regarding alcohol consumption in Slovenia? A focus group study. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2010;122:68–73.

Carlfjord S, Johansson K, Bendtsen P, et al. Staff perspectives on the use of a computer-based concept for lifestyle intervention implemented in primary health care. Health Educ J. 2010;69:246–56.

Wilson GB, Lock CA, Heather N, et al. Intervention against excessive alcohol consumption in primary health care: a survey of GPs’ attitudes and practices in England ten years on. Alcohol & Alcoholism 2011. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agr067

Kaner E, Rapley T, May C. Seeing through the glass darkly? A qualitative exploration of GPs’ drinking and their alcohol intervention practices. Fam Pract. 2006;23:481–7.

Ruf D, Berner M, Kriston L, et al. Cluster-randomized controlled trial of dissemination strategies of an online quality improvement programme for alcohol-related disorders. Alcohol Alcohol. 2010;45:70–8.

Williams EC, Lapham G, Achtmeyer CE, et al. Use of an electronic clinical reminder for brief alcohol counseling is associated with resolution of unhealthy alcohol use at follow-up screening. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:11–7.

Rose GL, Plante DA, Thomas CS, et al. Utility of prompting physicians for brief alcohol consumption intervention. Subst Use Misuse. 2010;45:936–50.

Nygaard P. and Aasland OG: Barriers to implementing screening and brief interventions in general practice: findings from a qualitative study in Norway. Alcohol Alcohol. 2011;46:52–60.

Nygaard P, Paschall MJ, Aasland OG, Lund KE. Use and barriers to use of screening and brief interventions for alcohol problems among Norwegian general practitioners. Alcohol Alcohol. 2010;45:207–12.

Nilsen PER. Brief alcohol intervention research and practice—towards a broader perspective. Addiction. 2010;105:964–5.

Kaner E. Brief alcohol intervention: time for translational research. Addiction. 2010;105:960–1.

Tsai YF, Tsai MC, Lin YP, et al. Facilitators and barriers to intervening for problem alcohol use. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66:1459–68.

• Swedish National Institute Of Public Health: Alcohol issues in daily healthcare: the risk drinking project—background, strategy and results. Swedish National Institute Of Public Health: Stockholm; 2010. This reports on an unprecedented initiative coordinated at national and organizational levels to implement BIs in health care settings.

Disclosure

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Wilson, G.B., Heather, N. & Kaner, E.F.S. New Developments in Brief Interventions to Treat Problem Drinking in Nonspecialty Health Care Settings. Curr Psychiatry Rep 13, 422–429 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-011-0219-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-011-0219-x