Abstract

Animal models may be useful in investigating the fundamental mechanisms underlying psychiatric disorders, and may contribute to the development of new medications. A computerized literature search was used to collect studies on recently developed animal models for anxiety disorders. Particular cognitive-affective processes (eg, fear conditioning, control of stereotypic movements, social submissiveness, and trauma sensitization) may be particularly relevant to understanding specific anxiety disorders. Delineation of the phenomenology and psychobiology of these processes in animals leads to a range of useful models of these conditions. These models demonstrate varying degrees of face, construct, and predictive validity.

Similar content being viewed by others

References and Recommended Reading

Shekhar A, McCann UD, Meaney MJ, et al.: Summary of a National Institute of Mental Health workshop: developing animal models of anxiety disorders. Psychopharmacology 2001, 157:327–339.

Martin P: Animal models sensitive to anti-anxiety agents. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1998, 98:74–80.

Pellow S, Chopin P, File SE, Briley M: Validation of open, closed arm entries in an elevated-plus maze as a measure of anxiety in the rat. J Neurosci Methods 1985, 14:149–167.

Treit D: Animal models for the study of anti-anxiety agents: a review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 1985, 9:203–222.

Weiss JM, Simson PG: Depression in an animal model: Focus on the locus coeruleus. In Antidepressants and Receptor Function. Edited by Weiss JM, Simson PG. New York: Wiley; 1986:191–216.

Mineka S, Zinbarg R: Conditioning and ethological models of anxiety disorders: stress in dynamic context anxiety models. The 43rd Annual Nebraska Symposium on Motivation. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; 1996:135–211.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, edn 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Press; 1994.

Garvey MJ, Noyes R Jr, Woodman C: The association of urinary 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid and vanillylmandelic acid in patients with generalized anxiety. Neuropsychobiology 1995, 31:6–9.

Tiihonen J, Kuikka J, Rasanen P et al.: Central benzodiazepine receptor binding and distribution in generalized anxiety disorder: a fractal analysis. Mol Psychiatry 1997, 2:463–471.

Ballenger JC: Current treatments of the anxiety disorders in adults. Biol Psychiatry 1999, 46:1579–1594.

Rickels K, Rynn MA: What is generalized anxiety disorder? J Clin Psychiatry 2001, 62(suppl):4–12.

Prut L, Belzung C: The open field as a paradigm to measure the effects of drugs on anxiety-like behaviors: a review. Eur J Pharmacol 2003, 463:3–33.

Sanchez C: Stress-induced vocalization in adult animals: a valid model of anxiety? Eu J Pharmacol 2003, 463:133–143.

Takahashi LK, Peng Ho S, Livanov V, et al.: Antagonism of CRF2 receptors produces anxiolytic behavior in animal models of anxiety. Brain Research 2001, 902:135–142.

Zorilla EP, Valdez GR, Nozulak J, et al.: Effects of antalarmin, a CRF type 1 receptor antagonist, on anxiety-like behavior and motor activation in the rat. Brain Research 2002, 952:188–199.

Zhuang X, Gross C, Santarelli L, et al.: Altered emotional states in knockout mice lacking 5-HT1A or 5-HT1B receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology 1999, 21:52S-60S. A study in which a 5-HT1A genetic knockout model was developed, emphasizing the importance of the 5-HT1A receptor in anxiety. 5-HT1A KOs showed more anxious behavior in the elevated plus maze than controls. This report emphasizes the importance of the amygdala NMDA and alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionate (AMPA) receptors in fear-learning and fear loss. N-methyl-D-aspartate and AMPA receptors appear important for fear-learning, whereas AMPA receptors also play an important role in fear-expression.

Sibille E, Pavlides C, Benke D, Toth M: Genetic inactivation of the serotonin 1A receptor in mice results in downregulation of major GABA(A) receptor alpha subunits, reduction of GABA(A) receptor binding, and benzodiazepine-resistant anxiety. J Neurosci 2000, 20:2758–2765.

Olivier B, Pattij T, Wood SJ, et al.: The 5-HT1A receptor knockout mouse and anxiety. Behav Pharmacol 2001, 12:439–450.

Hogg S: A review of the validity and variability of the elevated plus-maze as an animal model of anxiety. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1996, 54:21–30.

Silva RCB, Brandao ML: Acute and chronic effects of gepirone and fluoxetine in rats tested in the elevated plus-maze: an ethological analysis. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2000, 65:209–216.

Goodman WK, McDougle CJ, Price LH, et al.: Beyond the serotonin hypothesis: a role for dopamine in some forms of obsessive compulsive disorder? J Clin Psychiatry 1999, 51:S36-S43.

Harvey BH, Brink CB, Seedat S, Stein DJ: Defining the neuromolecular action of myo-inositol: application to obsessive compulsive disorder. Prog Neuro Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2002, 26:21–32.

Vythilingum B, Cartwright C, Hollander E: Pharmacotherapy of obsessive-compulsive disorder: experience with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2000, 15(suppl):7–13.

McDougle CJ, Epperson CN, Pelton GH, et al.: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of risperidone addition in serotonin reuptake inhibitor-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000, 57:794–801. This report emphasizes the importance of the amygdala NMDA and AMPA receptors in fear-learning and fear loss. N-methyl-D-aspartate and AMPA receptors appear important for fear-learning, whereas AMPA receptors also play an important role in fear-expression.

Leonard H, Swedo SE: Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infection (PANDAS). Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2001, 4:191–198.

Powell SB, Newman HA, Pendergast JF, Lewis MH: A rodent model of spontaneous stereotypy: initial characterization of developmental, environmental, and neurobiologic factors. Physiol Behav 1999, 66:355–363. This study reported the natural stereotypic behaviors emitted by deer mice, such as jumping and backward somersaulting, and suggested that natural stereotypic behaviors may be modulated by neurotransmitter systems different from drug-induced stereotypy. This report emphasizes the importance of the amygdala NMDA and AMPA receptors in fear-learning and fear loss. N-methyl-D-aspartate and AMPA receptors appear important for fear-learning, whereas AMPA receptors also play an important role in fear-expression.

Presti MF, Powell SB, Lewis MH: Dissociation between spontaneously emitted and apomorphine-induced stereotypy in Peromyscus maniculatus bairdii. Physiol Behav 2002, 75:347–353.

Turner CA, Yang MC, Lewis MH: Environmental enrichment: effects on stereotyped behavior and regional neuronal metabolic activity. Brain Res 2002, 938:15–21.

Presti MF, Mikes HM, Lewis MH: Selective blockade of spontaneous motor stereotypy via intrastriatal pharmacological manipulation. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2003, 74:833–839.

Rapoport J: An animal model of obsessive compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992, 49:517–521. This study reported that ALD, an animal grooming disorder, is reminiscent of OCD. Obsessive-compulsive disorder-effective pharmacotherapy was also effective in treating ALD symptoms. This report emphasizes the importance of the amygdala NMDA and AMPA receptors in fearlearning and fear loss. N-methyl-D-aspartate and AMPA receptors appear important for fear-learning, whereas AMPA receptors also play an important role in fear-expression.

Szechtman H, Sulis W, Eilam D: Quinpirole induces compulsive checking behavior in rats: a potential animal model of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Behav Neurosci 1998, 112:1475–1485.

Tizabi Y, Louis VA, Taylor CT, et al.: Effect of nicotine on quinpirole-induced checking behavior in rats: implications for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2002, 51:164–171.

Joel D, Doljansky J: Selective alleviation of compulsive lever-pressing in rats by D1 but not D2, blockade: possible implications for the involvement of D1 receptors in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacol 2003, 28:77–85.

Stein DJ, Seedat S, Potocnik F: Hoarding: a review. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci 1999, 36:35–46.

Hugo C, Seier J, Mdhluli C, et al.: Fluoxetine decreases stereotypic behavior in primates. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2003, 27:639–643. This report emphasizes the importance of the amygdala NMDA and AMPA receptors in fear-learning and fear loss. N-methyl-D-aspartate and AMPA receptors appear important for fear-learning, whereas AMPA receptors also play an important role in fear-expression.

Ernst AM, Smelik PG: Site of action of dopamine and apomorphine on compulsive gnawing behavior in rats. Experientia 1966, 22:837–838.

Dickson PR, Lang CG, Hinton SC, Kelley AE: Oral stereotypy induced by amphetamine microinjection into striatum: an anatomical mapping study. Neuroscience 1994, 61:81–91.

Harvey BH, Scheepers AS, Brand L, Stein DJ: Chronic inositol increases striatal D2 receptors but does not modify dex-amphetamine-induced motor behavior: relevance to obsessive compulsive disorder. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2001, 68:245–253.

Perlmutter SJ, Leitman S, Garvey MA, et al.: Therapeutic plasma exchange and intravenous immunoglobulin for obsessivecompulsive disorder and tic disorders in childhood. Lancet 1999, 354:1153–1158.

Taylor JR, Morshed SA, Parveen S, et al.: An animal model of Tourette’s syndrome. Am J Psychiatry 2002, 159:657–660.

Abelson JL, Glitz D, Cameron OG, et al.: Endocrine, cardiovascular and behavioral responses to clonidine in patients with panic disorder. Biol Psychiatry 1992, 32:18–25.

Coplan JD, Pine D, Papp LA, et al.: Noradrenergic/HPA-axis uncoupling in panic disorder. Neuropsychopharmacol 1995, 13:65–73.

Coplan JD, Papp LA, Pine DS, et al.: Clinical improvement with fluoxetine therapy and noradrenergic function in patients with panic disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997, 54:643–648.

Boyer W: Serotonin uptake inhibitors are superior to imipramine and alprazolam in alleviating panic attacks: a metaanalysis. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1995, 10:45–49.

Goddard AW, Woods SW, Sholomkas DE, et al.: Effects of the serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluvoxamine on yohimbineinduced anxiety in panic disorder. Psychiatry Res 1993, 48:119–133.

Sheehan DV: Current concepts in the treatment of panic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1999, 60:16–21.

Gorman JM, Kent JM, Sullivan GM, Coplan JD: Neuroanatomical hypothesis of panic disorder, revised. Am J Psychiatry 2000, 157:493–505.

LeDoux JE, Iwata J, Cicchetti P, Reis DJ: Different projections of the central amygdaloid nucleus mediate autonomic and behavioral correlates of conditioned fear. J Neurosci 1988, 8:2517–2519.

LeDoux J: Fear and the brain: where have we been, and where are we going. Biol Psychiatry 1998, 44:1229–1238.

Davis M: Are different parts of the extended amygdala involved in fear versus anxiety? Biol Psychiatry 1998, 44:1239–1247.

Hilton SM, Zybrozyna AW: Amygdaloid region for defense reactions and its efferent pathway to the brainstem. J Physiol 1963, 165:160–173.

Sanders SK, Shekhar A: Blockade of GABA receptors in the region of the anterior basolateral amygdala of rats elicits increases in heart rate and blood pressure. Brain Res 1991, 567:01–110.

Brown P: Physiology of startle phenomena. In Negative Motor Phenomena. Edited by Fahn S, Hallett M, Luders HO, Marsden CD. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1995:273–287.

Cassella JV, Davis M: Sensitization fear conditioning and pharmacological modulation of acoustic startle following lesions of the dorsal periaqueductal gray. Soc Neurosci Abstr 1984, 10:1067.

Jenck F, Moreau J-L, Martin JR: Dorsal periaductal gray-induced aversion as a stimulation of panic anxiety: elements of face and predictive validity. Psychiatry Res 1995, 57:181–191.

Vianna DML, Landeira-Fernandez J, Brandao ML: Dorsolateral and ventral regions of the periaqueductal gray matter are involved in distinct types of fear. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2001, 25:711–719.

Fendt M, Koch M, Schnitzler HU: Lesions of the central gray block conditioned fear as measured with the potentiated startle paradigm. Behav Brain Res 1996, 74:127–134.

Davis M: Diazepam and flurazepam: effects on conditioned fear as measured with the potentiated startle paradigm. Psychopharmacol 1979, 62:1–7.

Kehne JH, Cassella JV, Davis M: Anxiolytic effects of buspirone and gepirone in the fear-potentiated startle paradigm. Eur J Pharmacol 1988, 94:8–13.

Anthony EW, Nevins ME: Anxiolytic effects of N-methyl-Daspartate-associated glycine receptor ligands in the rat potentiated startle test. Eur J Pharmacol 1993, 250:317–324.

Graeff FG, Silveira MCL, Nogueira RL, et al.: Role of the amygdala and periaqueductal gray in anxiety and panic. Behav Brain Res 1993, 58:123–132.

Ballenger JC, Davidson JR, Lecrubier Y, et al.: Consensus statement on panic disorder from the international consensus group on depression and anxiety. J Clin Psychiatry 1998, 59(suppl):47–54.

Walker DL, Ressler KJ, Lu KT, Davis M: Facilitation of conditioned fear extinction by systemic administration of intra-amygdala infusions of D-cycloserine as assessed with fear-potentiated startle in rats. J Neurosci 2002, 22:2343–2351.

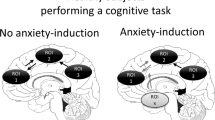

Walker DL, Davis M: The role of amygdala glutamate receptors in fear learning, fear-potentiated startle, and extinction. Pharmacol Biochemistry Behav 2002, 71:379–392. This report emphasizes the importance of the amygdala NMDA and AMPA receptors in fear-learning and fear loss. N-methyl-D-aspartate and AMPA receptors appear important for fear-learning, whereas AMPA receptors also play an important role in fear-expression.

Miyamoto Y, Yamada K, Noda Y, et al.: Lower sensitivity to stress and altered monoaminergic neuronal function in mice lacking the NMDA receptor epsilon 4 subunit. J Neurosci 2002, 22:2335–2342.

Walker DL, Davis M: Double dissociation between the involvement of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis and the central nucleus of the amygdala in light-enhanced versus fear-potentiated startle. J Neurosci 1997, 17:9375–9383.

Stanek L, Walker DL, Davis M: Amygdala infusion of LY354740, a group II metabotropic receptor agonist, blocks fear-potentiated startle in rats. Soc Neurosci Abstr 2000, 26:2020.

Rogòz Z, Skuza G, Maj J, Danysz W: Synergistic effects of uncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonists and antidepressant drugs in the forced swimming test in rats. Neuropharmacol 2002, 42:1024–1030.

Harvey BH, Jonker LP, Brand L, et al.: NMDA receptor involvement in imipramine withdrawal-associated effects on swim stress, GABA levels and NMDA receptor binding in rat hippocampus. Life Sci 2002, 71:43–54.

Krystal JH, Sanacora G, Blumberg H, et al.: Glutamate and GABA systems as targets for novel antidepressant and mood-stabilizing treatments. Mol Psychiatry 2002, 7(suppl):S71-S80.

Stewart CA, Reid IC: Antidepressant mechanisms: functional and molecular correlates of excitatory amino acid neurotransmission. Mol Psychiatry 2002 7(suppl_1):S15-S22.

Stein DJ, Westernberg HG, Liebowitz MR: Social anxiety disorder and generalized anxiety disorder: serotonergic and dopaminergic neurocircuitry, J Clin Psychiatry 2002, 63(suppl):12–19.

Sapolsky RM, Alberts SC, Altmann J: Hypercortisolism associated with social subordinance or social isolation among wild baboons. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997, 54:1137–1143. In this study, social affiliation in primates is associated with alterations in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function.

Uhde TW, Tancer ME, Gelernter CS, Vittone BJ: Normal urinary free cortisol and postdexamethasone cortisol in social phobia: comparison to normal volunteers. J Affect Disord 1994, 30:155–161.

Grant KA, Shively CA, Nader MA, et al.: Effect of social status on striatal dopamine D2 receptor binding characteristics in cynmolgus monkeys assessed with positron emission tomography. Synapse 1998, 29:80–83.

Schneier FR, Liebowitz MR, Abi-Dargham A, et al.: Low dopamine D2 receptor binding potential in social phobia. Am J Psychiatry 2000, 157:457–459.

Raleigh MJ, Brammer GL, McGuire MT, Yuwiler A: Dominant social status facilitates the behavioral effects of serotonergic agonists. Brain Res 1985, 348:274–282.

Stein DJ, Bouwer C: A neuro-evolutionary approach to the anxiety disorders. J Anxiety Disord 1997, 11:409–429.

Elzinga BM, Bremner JD: Are the neural substrates of memory the final common pathway in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)? J Affect Disord 2002, 70:1–17.

Yehuda R, Southwick SM, Krystal JH, et al.: Enhanced suppression of cortisol following dexamethasone administration in posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1993, 150:83–86.

Yehuda R, Siever L, Teicher MH, et al.: Plasma norepinephrine and MHPG concentrations and severity of depression in combat PTSD and major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry 1998, 44:56–63.

Pynoos RS, Ritzmann RF, Steinberg AM, et al.: A behavioral animal model of posttraumatic stress disorder featuring repeated exposure to situational reminders. Biol Psychiatry 1996, 39:129–134.

Liberzon I, Krstov M, Young EA: Stress-restress: effects on ACTH and fast feedback. Psychoneuroendocrinol 1997, 22:443–453. In this study, a single exposure to prolonged stress is followed by a reexposure to one of the stressors 7 days later. Animals showed sensitization of the feedback inhibition of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, which corresponds with alterations seen in PTSD.

Richter-Levin G: Acute and long-term behavioral correlates of underwater trauma-potential relevance to stress and poststress syndromes. Psychiatry Res 1998, 79:73–83.

Adamec RE, Shallow T: Lasting effects on rodent anxiety of a single exposure to a cat. Physiol Behav 1993, 54:101–109.

Cohen H, Zohar J, Matar M: The relevance of differential response to trauma in an animal model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2003, 53:463–473.

Heim C, Nemeroff CB: The role of childhood trauma in the neurobiology of mood and anxiety disorders: preclinical and clinical studies. Biol Psychiatry 2001, 49:1023–1039.

Coplan JD, Andrews MW, Rosenblum LA, et al.: Persistent elevations of cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of corticotropinreleasing factor in adult nonhuman primates exposed to early-life stressors: Implications for the pathophysiology of mood and anxiety disorders. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996, 93:1619–1623.

Yehuda R, Antelman SM: Criteria for evaluating animal models of posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry 1993, 33:479–486. This review differentiates criteria that are essential in putative animal models of PTSD, and will allow them to more closely model human PTSD. Animal models that adhere closest to a set of five criteria will afford them greater value in studies aimed at understanding the neurobiology and pharmacology of the illness.

Liberzon I, Lopez F, Flagel SB, et al.: Differential regulation of hippocampal glucocorticoid receptor mRNA and fast feedback: relevance to post-traumatic stress disorder. Neuroendocrinology 1999, 11:11–17.

Harvey BH, Naciti C, Brand L, Stein DJ: Endocrine, cognitive and hippocampal/cortical 5HT1A/2A receptor changes evoked by a time dependent sensitisation (TDS) stress model in rats. Brain Res 2003, in press.

Harvey BH, Naciti C, Brand L, Stein DJ: Cognitive and hippocampal. cortical 5-HT1A/2A-receptor changes evoked by a stress-restress paradigm are modulated by ketoconazole and serotonergic-active drugs. Paper presented at The 34th Annual Congress of the International Society for Psychoneuroendocrinology. New York; September 7–9, 2003.

Oosthuizen F, Brand L, Wegener G, et al.: Sustained effects on NO synthase activity, GABA levels, and NMDA receptors in the hippocampus of rats subjected to stress-restress. Paper presented at The 6th Annual Conference of the International Brain Research Organization. Prague; July 10–15, 2003.

Segman RH, Cooper-Kazaz R, Macciardi F, et al.: Association between the dopamine transporter gene and posttraumatic stress disorder. Mol Psychiatry 2002, 7:903–907.

King JA, Abend S, Edwards E: Genetic predisposition and development of posttraumatic stress disorder in an animal model. Biol Psychiatry 2001, 50:231–237. This is the first study in which a genetic, PTSD preclinical model was developed using rats that exhibited helplessness criteria after stress exposure.

van der Kolk BA, Greenberg MS, Orr SP, Pitman RK: Endogenous opioids, stress induced analgesia, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull 1989, 25:417–421.

Golier J, Yehuda R: Neuroendocrine activity and memoryrelated impairments in posttraumatic stress disorder. Dev Psychopathol 1998, 10:857–869.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Uys, J.D.K., Stein, D.J., Daniels, W.M.U. et al. Animal models of anxiety disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep 5, 274–281 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-003-0056-7

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-003-0056-7