Abstract

Where to treat patients is probably the single most important decision in the management of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), with a substantial impact on both patients’ outcomes and health-care costs. Several factors can contribute to the decision of the site of care for CAP patients, including physicians’ experience and clinical judgment and severity scores developed to predict mortality, as well as social and health-care-related issues. The recognition, both in the community and in the emergency department, of the presence of severe sepsis and acute respiratory failure and the coexistence with unstable comorbidities other than CAP are indications for hospital admission. In all the other cases, physician’s choice to admit CAP patients should be validated against at least one objective tool of risk assessment, with a clear understanding of each score’s limitations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the U.S., community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) accounts for 4 million episodes of illness each year and represents the most common lethal infectious disease. More than one million people require hospital admission annually because of CAP, with health-care costs up to $10 billion. The vast majority of the latter is due to hospitalization, and the total fixed inpatient costs are calculated at $8.6 billion per year [1].

The site of care (home, hospital ward, or intensive care unit [ICU]) is probably the single most important decision in the management of patients with CAP, having a substantial impact on both patient’s outcomes and health-care costs. National and international guidelines agree that the assessment of severity represents the first step in the management algorithm of a CAP patient [2–4]. Several factors contribute to the evaluation of the severity of disease and to the decision as to the site of care of CAP patients. These include the physician’s clinical judgment and severity scores able to predict mortality, as well as social and health-care-related issues. The aim of the following review is to evaluate some critical aspects related to hospital admission decisions in CAP patients and to give some new perspectives on this topic.

Patients with Severe CAP Need to Be Hospitalized

There is no doubt that a patient with a severe CAP requires hospitalization. The question is, what is severe CAP, and can we use scores to define a severe CAP. So far, there is no generally accepted definition for severe CAP. The most widely used surrogate for high-risk prediction is the admission to an ICU, and several authors have independently described, in large databases, scoring systems to predict this outcome.

The tool currently recommended by guidelines in deciding ICU admission is the Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society score that includes major and minor criteria [2]. While the major criteria include the need for mechanical ventilation or the presence of septic shock requiring vasopressors, the minor criteria consist of nine physiological and laboratory parameters, with three or more among those indicating severe CAP requiring ICU admission [5, 6]. Other physiological scoring systems have been proposed during the past decade, primarily aimed to improve the prediction of ICU admission, such as the PIRO [7], SMART-COP [8], ADROP [9], CORB [10], the REAICU-rule [11], and SCAP [12, 13] scores. Most of these prediction rules vary in complexity and suffer from specific limitations or the absence of additional validation; thus, further research is needed before they should be used in clinical practice.

The abundance of these severity criteria reveals a lack of consensus over which patients should be initially managed in the ICU and what a severe CAP is. The use of ICU admission as a marker of severe CAP is vulnerable to several biases. Rates and criteria for admission to ICU vary widely across units and different health-care systems, and they are highly dependent on individual physician decisions [14].

Although mortality and ICU admission are the main outcomes in the majority of studies on CAP, it seems that the presence of severe sepsis (with or without the need for vasopressor support) and/or the presence of acute respiratory failure (with or without the need for mechanical ventilation) are simple and useful outcomes for identifying the most acutely ill patients who require hospitalization. From a pathophysiological point of view, the presence of at least one of these two conditions or other unstable comorbidities during the evaluation of a CAP patient in the community setting, or in an emergency department, can lead directly to hospital admission.

Clinical Judgment Alone Could Not Be Enough in Nonsevere CAP

A wide variation in the management of patients with CAP has been identified among different hospital settings [15]. Dean and coworkers found individual emergency physician admission rates for CAP patients ranging from 38 % to 79 %, and this variability was not explained by objective data [16]. It seems that when relying on clinical judgment alone, clinicians may over- or underestimate the severity of CAP, leading to potentially inappropriate treatment decisions. In one experience, 292 physicians were asked to estimate the risk of mortality for CAP patients, all of whom had an estimated mortality <4 % and were potentially suitable for outpatient care according to objective parameters. A total of 41 % of the inpatients included in the study were judged by physicians to have a risk of mortality >5 % and to require admission [17]. In another study, only 7 % of physicians had correct assessments of pneumonia severity similar to those assigned by the objective parameters [18].

This evidence supports recommendations by the majority of guidelines on the use of severity assessment tools as objective methods for complementing clinical judgment in the evaluation of the severity of disease in CAP patients [2–4]. These scoring systems have been developed and validated with mortality as the main outcome, but also length of stay and time to clinical stability [19–21]. The scoring systems have been shown to assist physicians in stratifying patients into useful groups, such as low, intermediate, and high risk for death.

The Ability of the Severity Scores to Predict Mortality in CAP Patients

The Severity Scores

The most rigorous studied and established severity prediction tool in CAP is the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI), which stratifies patients with CAP on the basis of the risk of death within 30 days [19]. This score is based on 20 different variables from data validated on more than 40,000 inpatients (see Table 1). It categorizes patients into five risk classes: classes I and II are at low risk of mortality (0.1 %–0.7 %), patients in class III are also at relatively low risk of death (0.9 %–2.8 %), patients in class IV have an increased risk (4 %–10 %), and class V patients are at the highest risk of 30-day mortality (27 %).

The British Thoracic Society established a severity score composed of four variables that were shown to be predictive of death from pneumonia: the presence of confusion on admission (C) respiratory rate (R) ≥30/min, diastolic blood pressure (B) ≤60 mmHg, and a blood urea nitrogen (U) >20 mg/dL [20]. A modified 6-point CURB-65 score (as above, plus age ≥65 years) was derived on the basis of a multivariate analysis of 1,068 patients and extensively validated in over 15,000 subjects [22] and divides patients into three broad risk groups: scores 0–1 at low risk (0.7 %–3.2 %), score 2 at intermediate risk (13 %), and scores 3–5 at high risk of 30-day mortality (17 %–57 %) (see Table 2). A CRB-65 score has been developed as a simplified modification of this severity scoring system with the omission of blood urea testing. It demonstrated equivalence in risk stratification, as compared with both the PSI and CURB-65, and it has been suggested as a tool in the offices of primary care physicians to determine whether severity is high enough to warrant hospital admission [23, 24].

Can Severity Scores Predict Mortality?

In a recent systematic review, Chalmers and coworkers compared the performance characteristics of the PSI, CURB-65, and CRB-65 scores for predicting 30-day mortality in CAP patients, and they found moderate to good accuracy [25••]. No significant differences were identified in overall test performance between these scores for predicting mortality, and their performance characteristics were similar across comparable cutoffs for low, intermediate, and high risk for each score (see Fig. 1). However, in identifying low-risk patients, the PSI (groups I and II) had the best negative likelihood ratio, as compared with CURB-65 and CRB-65, suggesting that the PSI may be superior at identifying low-risk patients, while a higher positive predictive value suggested that CURB-65/CRB-65 may be superior for identifying high-risk patients. The strengths and weaknesses of these scores with respect to predicting pneumonia-related mortality have been recently evaluated [26].

Receiver operator characteristic curves for the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI), CURB65, and CRB65 with respect to mortality [25••]. AUC, area under the curve

Severity Scores in Special Populations

Severity scoring systems may not identify all patients at risk, and a recalibration of these scores may be needed when transporting them across special populations.

A recent paper demonstrated that females have worse outcomes for CAP than do males [27]. Particularly, females are more likely to take longer to reach clinical stability, have longer hospital stays, and are 15 % more likely to be dead after 28 days. In view of these data, current pneumonia scoring systems may need to be revised regarding female mortality risk.

Age-related alterations in the clinical characteristics and performance of severity scoring systems for CAP are important. It is not surprising that because of the high incidence of comorbidities and poor functional status, these patients show a high mortality rate. Some studies have been specifically designed to evaluate severity scores in elderly patients with CAP [28, 29]. An interesting analysis was conducted in order to compare the predictive value of CURB-65 and PSI in adult (18–65), elderly (65–84), and very elderly (85+) patients [30]. Both PSI and CURB-65 performed relatively well in the first two cohorts but poorly in the very elderly. Moreover, both PSI and CURB-65 seem to have no prognostic value in geriatric patients who are hospitalized with aspiration pneumonia [31].

The role of the severity scores in patients with health-care-associated pneumonia (HCAP) is currently uncertain, mainly because these patients are at high risk of death and a large proportion are likely to require hospitalization [32]. In a multicenter, prospective, observational study, Falcone and coworkers showed that PSI and CURB-65 have a good performance in patients with CAP but are less useful in those with HCAP, in view of the fact that “low-risk” patients with HCAP seem to have a relatively high mortality [33].

Current pneumonia severity scores have been recently evaluated during pandemic influenza. Data from both retrospective and prospective trials demonstrated that they have insufficient predictive ability to safely identify low-risk patients with pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza and often fail to predict CAP severity or the need for ICU admission [34–38]. More than 300 H1N1 patients were evaluated by Bjarnason et al. in a prospective, population-based study in Iceland. These patients showed significantly lower severity scores than did CAP patients and were more likely to require intensive care admission (41 % vs. 5 %) and receive mechanical ventilation (14 % vs. 2 %) [35]. A similar experience has been conducted in Australia showing that the PSI and CURB-65 cannot provide good discrimination of low-risk patients, with 19 % and 21 %, respectively, of H1N1 2009 influenza patients requiring ICU admission as predicted by the scores [37].

Doubts in the predictability of the most important score systems for CAP have also been raised in other populations, such as cancer patients [39], those with a non-HIV P. jiroveci pneumonia [40], or young patients with community-acquired methicillin-resistant S. aureus [41].

Implementing Severity Scores with Biomarkers

Several efforts have recently been made to incorporate different biomarkers with clinical criteria in order to improve the prediction of mortality for CAP patients [42]. The rationale is mainly based on the theoretical capability of these biomarkers to detect underlying mechanisms of CAP progression more accurately and in a more timely fashion. Procalcitonin (PCT) levels on admission seem to predict the severity and outcome of CAP with a prognostic accuracy similar to the CURB-65 score [43], and adding PCT for patients assessed to be at high risk on the basis of the PSI score significantly improved the ability to rule out the likelihood of death [44]. Proadrenomedullin (proADM) has been shown to perform better than PCT and to correlate with increasing severity of illness and short-term mortality, as well as long-term outcomes [45, 46•]. Combination of the PSI and proADM allows a better risk assessment than PSI alone [47]. Finally, a composite score (CURB65-A) has been proposed combining CURB-65 classes with proADM cutoffs in patients with CAP and non-CAP lower respiratory tract infections [48]. The predictive value of other biomarkers, such as proatrial natriuretic peptide, provasopressin, and cortisol, has recently been investigated in CAP [49–51].

The full clinical value of these biomarkers still remains uncertain, and they are currently limited by the absence of a rapid availability, high cost, and problems identifying cutoff points for different clinical settings/populations. Furthermore, additional prospective cohort and clinical intervention trials are required to confirm any additional benefit of biomarkers in the clinical management of CAP patients.

The Relation Between the Risk of Death and the Need for Hospitalization in CAP Patients

The PSI and the CURB-65 score have been shown to separate patients into clinically useful subgroups for prediction of mortality, and national and international guidelines suggest that these tools aid clinical judgment in site-of-care decision [3, 4]. The PSI risk classes I and II were recommended for outpatient treatment, as well as class III without evidence of oxygen desaturation. Patients in classes IV and V were recommended to be managed as inpatients in the majority of cases. Although the CURB-65 score was not developed to identify patients suitable for discharge, it has been suggested that patients with a score of 0 or 1 may be treated as outpatients, and patients with a score of 2 require a short hospitalization, while patients with a score of 3 require hospitalization [4].

During the past decade, several studies wherein the PSI score was incorporated into a clinical pathway for the management of CAP demonstrated a reduction in hospitalizations for CAP patients in the “low-risk” classes. Interventional trials evaluating accurate identification of low-risk patients suitable for ambulatory treatment without compromising their safety have been performed only for the PSI score [52–55]. A prospective, observational, controlled cohort study of 925 CAP patients was performed in France by Renaud and coworkers in eight emergency departments (EDs) that used the PSI and eight EDs that did not use the PSI [56]. The authors found that routine use of the PSI was associated with a larger proportion of CAP patients with a PSI risk class of I or II, who were safely treated in the outpatient environment. The implementation of the PSI seems to result in a significant increase in patients managed in the community, without an increase in mortality or hospital readmissions or any change in the proportion of patients satisfied with their care [57, 58].

Moving from clinical trials to clinical practice, there still remains the question of how to appropriately use these severity scores, which were primarily validated to predict mortality rather than hospital discharge. Mortality has been applied as a surrogate for deciding the initial site of care, and recommendations made by national and international societies are based on the assumption that there is a linear relationship between the risk of death and the need for hospitalization. However, hospital discharge is a more difficult end point to study, since it is highly dependent on physician practice and local health-care policies.

Several studies have shown that despite intense efforts to implement a severity score-based guideline to identify low-risk patients with CAP for outpatient treatment, physicians tend to use their clinical judgment to hospitalize patients with a PSI risk class I or II 19 %–84 % of the time [52, 54–56, 59]. There are justified reasons for admitting patients with low PSI risk classes. A relevant percentage of these patients may suffer one or more complications, while 4 %–5 % may require ICU admission or die [60–62]. First of all, a major limitation of the PSI is the unbalanced impact of age on the score, resulting in a potential underestimation of severe pneumonia, particularly in younger, otherwise healthy individuals [63]. Severely ill younger patients may not receive a high score and may be inappropriately managed as outpatients. Other problems, such as the presence of medical conditions other than CAP, failure of outpatient therapy, inability to take oral medication, noncompliance, hypoxemia with the need for oxygen therapy, psychiatric comorbidities, social circumstances, or inadequate home support, are not fully captured by the PSI, and these patients may require hospitalization regardless of their prediction of mortality [23, 59, 61, 63–66, 67•]. On the other hand, some experience has shown that physicians tend to discharge 3 %–13 % of higher risk patients on the basis of the PSI, and the most common explanations are patient or family preferences, despite the primary care or consulting physician's recommendation for admission [52, 54, 56, 67•, 68].

If CURB-65 is used as an aid to clinical judgment in the site-of-care decision, several limitations should also be kept in mind, especially the fact that this score underestimates severity in young patients [69–71]. Two recent studies found reasons that justified hospitalization in more than 80 % of patients with a CURB-65 score of 0 or 1 [72, 73]. In an observational, retrospective study of consecutive CAP patients, the main reasons for hospitalization of patients with a CURB-65 score of 0 or 1 included the presence of hypoxemia on admission (35 %), failure of outpatient therapy (14 %), and the presence of cardiovascular events on admission (9.7 %) [72]. The importance of hypoxemia on admission in CAP patients with a CURB-65 score of 0 or 1 has been recently pointed out in a multicenter prospective cohort study showing that hypoxemia is independently associated with several adverse clinical and radiological variables [74]. Therefore, additional attention should be paid to the presence of hypoxemia, regardless of a low CURB-65 score.

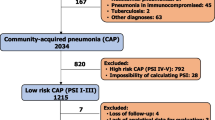

An effort has been recently made to develop a better algorithm to guide the site-of-care decision on the basis of the evaluation of critical organ dysfunction as a consequence of respiratory, cardiocirculatory, or comorbidity-related deterioration [75••]. A proposal of an integrated, two-step approach is depicted in Fig. 2. The first step is focused on a rapid rule-out of the presence of acute respiratory failure, severe sepsis, and/or unstable conditions that would require hospitalization for CAP patients. In the absence of these conditions, clinical judgment should be validated against at least one objective tool of risk assessment, having clearly in mind each score’s limitations. Once the decision to hospitalize a CAP patient has been made, the presence and the severity of both acute respiratory failure and severe sepsis could also be used for the site-of-care decision among different hospital units (general ward vs. high dependence unit vs. intensive care unit).

Proposed algorithm for hospital admission in patients with community-acquired pneumonia [modified after 75••]

Do Physicians Use Severity Scores in Clinical Practice in the Site-of-Care Decision for CAP Patients?

Reports of the use of severity criteria to guide site-of-care decisions in clinical practice are few, but they suggest that scoring systems are underutilized. The pneumonia severity index is relatively complex, requiring 20 different parameters with different weights. As a consequence, emergency departments that have implemented the PSI reported difficulties with encouraging staff to use it. In an audit by Lee et al., in a PSI user department in Australia, this score was used in only one third of cases and, when used, was calculated incorrectly in 42 % of cases [76]. When junior doctors were interviewed on the role of severity scores in a hospital, only 4 % named the CURB-65 score when asked to name the top criteria used to assess severity in CAP patients, and only 7 % were able to recall the score from memory and apply this to different scenarios [18]. Similar data have also been reported in two other studies [77, 78]. Serisier et al. recently submitted a survey of respiratory and emergency medicine physicians and specialist registrar members of their Royal Australasian Colleges in order to assess the use of the PSI and CURB-65 scores [79]. Only 12 % of respiratory and 35 % of emergency physicians reported using the PSI always or frequently. The majority of them were unable to accurately approximate the PSI score, with significantly fewer respiratory than emergency physicians recording accurate severity classes. On the other hand, significantly more respiratory physicians were able to accurately calculate the CURB-65 score. Implementation studies aimed to evaluate the use of severity scores in clinical practice are required.

The Site-of-Care Decision for CAP Patients in the Community

The recognition of the presence of acute respiratory failure, early signs/symptoms of severe sepsis, and the presence of unstable conditions other than CAP is a crucial step in the decision to send a CAP patient from the community to the hospital. In other circumstances, a tool that aids clinical judgment in the evaluation of the severity of the disease in an outpatient with CAP is required. The majority of the data focused on severity scores were derived and validated in terms of prognostic accuracy in hospitalized patients, and there are relatively few data on the use of scoring systems in outpatient settings [80]. Although, the CRB-65 score was originally recommended for outpatient use, only one validation study has been published, and it is limited to patients aged >65 years [81]. In a recent meta-analysis, CRB-65 and PSI seem to be good in identifying patients who are at a low risk of death and, therefore, may be confidently managed as outpatients, while neither the PSI nor the CRB-65 score shows superiority in this regard [80]. On the other hand, another systematic review and meta-analysis of validation studies of CRB-65 conducted in community settings pointed out that the CRB-65 seems to overpredict the probability of 30-day mortality across all strata of predicted risk [82]. The authors concluded that caution is needed when applying CRB-65 to patients in general practice.

Moving from clinical research to clinical practice, an interesting study has recently been published by Francis et al. among primary care clinicians in 13 European countries, including more than 3,300 subjects, to assess compliance of clinicians with the CRB-65 [83]. Primary care clinicians recorded the components required to calculate a CRB-65 prediction score in only a minority of patients; the respiratory rate and blood pressure were recorded in fewer than a quarter and in fewer than a third of the subjects, respectively. The CRB-65 also suffers from all the limitations previously discussed regarding the CURB-65, and more research is needed to confirm whether this score has value in managing CAP in the community.

The Use of Severity Scores in Clinical Research

Severity scores for CAP are currently used in clinical research in order to adjust data on the basis of patients’ characteristics that may influence clinical outcomes. In a prospective study, Silber and coworkers sought to determine the time to clinical stability in CAP patients on the basis of how quickly they received antibiotics [84]. Three groups of patients were developed on the basis of when antibiotics were given, and time to clinical stability and length of hospital stay were selected as outcomes for each group. To adjust for patient characteristics that may have influenced study outcomes, the mean PSI was reported for each group with statistical values that showed no significant difference.

Several other studies also used PSI and CURB-65 as indicators of severity of the disease on admission in CAP patients to adjust predictive variables with respect to late clinical outcomes in multivariable logistic regression analysis and propensity-weighted adjusted models [85–87].

Conclusions

The decision to hospitalize a patient with CAP is mostly determined from a clinical perspective. The recognition in the community, clinics, or emergency department of the presence of severe sepsis and acute respiratory failure or the coexistence with other unstable comorbidities is an indication for hospital admission. Once the decision to hospitalize a CAP patient is taken, the site of care (general ward, high dependency units, or ICU) should be based on the number, type, and degree of organ failures. In all other patients, the choice to admit a CAP patient should be validated against at least one objective tool of risk assessment, having clearly in mind each score’s limitations. Finally, different centers should consider different pathways in deciding hospital admission for a CAP patient on the basis of local health-care setting and resources.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Raut M, Schein J, Mody S, et al. Estimating the economic impact of a half-day reduction in length of hospital stay among patients with community-acquired pneumonia in the US. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25:2151–7.

Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44 Suppl 2:S27–72.

Woodhead M, Blasi F, Ewig S, et al. Guidelines for the management of adult lower respiratory tract infections–full version. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17 Suppl 6:E1–59.

Lim WS, Baudouin SV, George RC, et al. BTS guidelines for the management of community acquired pneumonia in adults: update 2009. Thorax. 2009;64 Suppl 3:iii1–55.

Chalmers JD, Taylor J, Mandal P, et al. Validation of the IDSA/ATS minor criteria for ICU admission in communityacquired pneumonia patients without major criteria or contraindications to ICU care. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:107–13.

Phua J, See KC, Chan YH, et al. Validation and clinical implications of the IDSA/ATS minor criteria for severe communityacquired pneumonia. Thorax. 2009;64:598–603.

Rello J, Rodriguez A, Lisboa T, et al. PIRO score for community-acquired pneumonia: a new prediction rule for assessment of severity in intensive care unit patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:456–62.

Charles PG, Wolfe R, Whitby M, et al. SMART-COP: a tool for predicting the need for intensive respiratory or vasopressor support in community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:375–84.

Kohno S, Seki M, Watanabe A. Evaluation of an assessment system for the JRS 2005: A-DROP for the management of CAP in adults. Intern Med. 2011;50:1183–91.

Buising KL, Thursky KA, Black JF, et al. Identifying severe community-acquired pneumonia in the emergency department: a simple clinical prediction tool. Emerg Med Australas. 2007;19:418–26.

Renaud B, Labarere J, Coma E, et al. Risk stratification of early admission to the intensive care unit of patients with no major criteria of severe community-acquired pneumonia: development of an international prediction rule. Crit Care. 2009;13:R54.

Espana PP, Capelastegui A, Gorordo I, et al. Development and validation of a clinical prediction rule for severe communityacquired pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:1249–56.

Yandiola PP, Capelastegui A, Quintana J, et al. Prospective comparison of severity scores for predicting clinically relevant outcomes for patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2009;135:1572–9.

Chalmers JD, Mandal P, Singanayagam A, et al. Severity assessment tools to guide ICU admission in community-acquired pneumonia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37:1409–20.

Jin Y, Marrie TJ, Carriere KC, et al. Variation in management of community-acquired pneumonia requiring admission to Alberta. Canada hospitals. Epidemiol Infect. 2003;130:41–5.

Dean NC, Jones JP, Aronsky D, et al. Hospital admission decision for patients with community-acquired pneumonia: variability among physicians in an emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;59:35–41.

Fine MJ, Hough LJ, Medsger AR, et al. The hospital admission decision for patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Results from the pneumonia Patient Outcomes Research Team cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:36–44.

Barlow G, Nathwani D, Myers E, et al. Identifying barriers to the rapid administration appropriate antibiotics in communityacquired pneumonia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61:442–51.

Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM, et al. A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:243–50.

Woodhead M. Assessment of illness severity in community acquired pneumonia: a useful new prediction tool? Thorax. 2003;58:371–2.

Arnold F, LaJoie A, Marrie T, et al. The pneumonia severity index predicts time to clinical stability in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10:739–43.

Lim WS, van der Eerden MM, Laing R, et al. Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on presentation to hospital: an international derivation and validation study. Thorax. 2003;58:377–82.

Capelastegui A, España PP, Quintana JM, et al. Validation of a predictive rule for the management of community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2006;27:151–7.

Bauer TT, Ewig S, Marre R, et al. CRB-65 predicts death from community-acquired pneumonia. J Intern Med. 2006;260:93–101.

•• Chalmers JD, Singanayagam A, Akram AR, et al. Severity assessment tools for predicting mortality in hospitalised patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax. 2010;65(10):878–83. This is a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 40 studies focused on prognostic information of PSI, CURB-65, and CRB-65 and showing no significant differences in overall test performance among the three scores for predicting mortality from community-acquired pneumonia.

Loke YK, Kwok CS, Niruban A, Myint PK. Value of severity scales in predicting mortality from community-acquired pneumonia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax. 2010;65:884–90.

Arnold FW, Wiemken T, Peyrani P, et al. Outcomes in females hospitalised with community-acquired pneumonia are worse than males. Eur Respir J. 2012 Jul 26. [Epub ahead of print]

Parsonage M, Nathwani D, Davey P, Barlow G. Evaluation of the performance of CURB-65 with increasing age. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15:858–64.

Myint PK, Kamath AV, Vowler SL, et al. The CURB (confusion, urea, respiratory rate and blood pressure) criteria in community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) in hospitalised elderly patients aged 65 years and over: a prospective observational cohort study. Age Ageing. 2005;34:75–7.

Chen JH, Chang SS, Liu JJ, et al. Comparison of clinical characteristics and performance of pneumonia severity score and CURB-65 among younger adults, elderly and very old subjects. Thorax. 2010;65:971–7.

Heppner HJ, Sehlhoff B, Niklaus D, et al. Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI), CURB-65, and mortality in hospitalized elderly patients with aspiration pneumonia. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2011;44:229–34.

Fang WF, Yang KY, Wu CL, et al. Application and comparison of severity indices to predict outcomes in patients with healthcare-associated pneumonia. Crit Care. 2011;15:R32.

Falcone M, Corrao S, Venditti M, et al. Performance of PSI, CURB-65, and SCAP scores in predicting the outcome of patients with community-acquired and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Intern Emerg Med. 2011;6:431–6.

Mulrennan S, Tempone SS, Ling IT, et al. Pandemic influenza (H1N1) 2009 pneumonia: CURB-65 score for predicting severity and nasopharyngeal sampling for diagnosis are unreliable. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12849.

Bjarnason A, Thorleifsdottir G, Löve A, et al. Severity of Influenza A 2009 (H1N1) pneumonia is underestimated by routine prediction rules. Results from a prospective, population-based study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46816.

Myles PR, Nguyen-Van-Tam JS, Lim WS, et al. Comparison of CATs, CURB-65 and PMEWS as triage tools in pandemic influenza admissions to UK hospitals: case control analysis using retrospective data. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34428.

Commons RJ, Denholm J. Triaging pandemic flu: pneumonia severity scores are not the answer. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16:670–3.

Pereira JM, Moreno RP, Matos R, et al. Severity assessment tools in ICU patients with 2009 Influenza A (H1N1) pneumonia. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:1040–8.

Aliberti S, Brock GN, Peyrani P, et al. The pneumonia severity index and the CRB-65 in cancer patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009;13:1550–6.

Asai N, Motojima S, Ohkuni Y, et al. Non-HIV Pneumocystis pneumonia: do conventional community-acquired pneumonia guidelines under estimate its severity? Multidiscip Respir Med. 2012;11(7):2.

Nathwani D, Morgan M, Masterton RG, et al. Guidelines for UK practice for the diagnosis and management of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections presenting in the community. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61:976–94.

Menéndez R, Martínez R, Reyes S, et al. Biomarkers improve mortality prediction by prognostic scales in community-acquired pneumonia. Thorax. 2009;64:587–91.

Krüger S, Ewig S, Marre R, et al. Procalcitonin predicts patients at low risk of death from community-acquired pneumonia across all CRB-65 classes. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:349–55.

Huang DT, Weissfeld LA, Kellum JA, et al. Risk prediction with procalcitonin and clinical rules in community-acquired pneumonia. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:48–58.

Huang DT, Angus DC, Kellum JA, et al. Midregional proadrenomedullin as a prognostic tool in community acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2009;136:823–31.

• Krüger S, Ewig S, Giersdorf S, et al. Cardiovascular and inflammatory biomarkers to predict short- and longterm survival in community-acquired pneumonia: results from the German Competence Network, CAPNETZ. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:1426–34. In this study, performed on more than 700 patients with CAP, the authors showed proadrenomedullin, proatrial natriuretic peptide, and copeptin to be good predictors of short- and long-term all-cause mortality, superior to inflammatory markers and at least comparable to CRB-65 score.

Courtais C, Kuster N, Dupuy AM, et al. Proadrenomedullin, a useful tool for risk stratification in high Pneumonia Severity Index score community acquired pneumonia. Am J Emerg Med. 2012. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2012.07.017.

Albrich WC, Dusemund F, Rüegger K, et al. Enhancement of CURB65 score with proadrenomedullin (CURB65-A) for outcome prediction in lower respiratory tract infections: derivation of a clinical algorithm. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;3(11):112.

Krüger S, Papassotiriou J, Marre R, et al. Pro-atrial natriuretic peptide and pro-vasopressin to predict severity and prognosis in community-acquired pneumonia: results from the German competence network CAPNETZ. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:2069–78.

Kolditz M, Höffken G, Martus P, et al. Serum cortisol predicts death and critical disease independently of CRB-65 score in community-acquired pneumonia: a prospective observational cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;13(12):90.

Christ-Crain M, Stolz D, Jutla S, et al. Free and total cortisol levels as predictors of severity and outcome in community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:913–20.

Marrie TJ, Lau CY, Wheeler SL, et al. A controlled trial of a critical pathway for treatment of community-acquired pneumonia.CAPITAL Study Investigators. Community-Acquired Pneumonia Intervention Trial Assessing Levofloxacin. JAMA. 2000;283:749–55.

Carratala J, Fernandez-Sabe N, Ortega L, et al. Outpatient care compared with hospitalization for community-acquired pneumonia: a randomized trial in low-risk patients. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:165–72.

Yealy DM, Auble TE, Stone RA, et al. Effect of increasing the intensity of implementing pneumonia guidelines: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:881–94.

Atlas SJ, Benzer TI, Borowsky LH, et al. Safely increasing the proportion of patients with community-acquired pneumonia treated as outpatients: an interventional trial. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1350–6.

Renaud B, Coma E, Labarere J, et al. Routine use of the pneumonia severity index for guiding the site-of-treatment decision of patients with pneumonia in the emergency department: a multicenter, prospective, observational, controlled cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:41–9.

Jo S, Kim K, Jung K, et al. The effects of incorporating a pneumonia severity index into the admission protocol for community-acquired pneumonia. J Emerg Med 2010 [epub ahead of print].

Chalmers JD, Akram AR, Hill AT. Increasing outpatient treatment of mild community-acquired pneumonia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2011;37:858–64.

Seymann G, Barger K, Choo S, et al. Clinical judgment versus the Pneumonia Severity Index in making the admission decision. J Emerg Med. 2008;34:261–8.

Marrie TJ, Huang JQ. Low-risk patients admitted with community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Med. 2005;118:1357–63.

Arnold FW, Ramirez JA, McDonald LC, Xia EL. Hospitalization for communityacquired pneumonia: the pneumonia severity index vs clinical judgement. Chest. 2003;124:121–4.

Chan SS. The Pneumonia Severity Index as a decision-making tool to guide patient disposition. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20:387–8.

Ewig S, de Roux A, Garcia E, et al. Validation of predictive rules and indices of severity for community-acquired pneumonia. Thorax. 2004;59:421–7.

Goss CH, Rubenfeld GD, Park DR, et al. Cost and incidence of social comorbidities in low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia admitted to a public hospital. Chest. 2003;124:2148–55.

Marras TK, Gutierrez C, Chan CK. Applying a prediction rule to iden tify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2000;118:1339–43.

Espana PP, Capelastegui A, Quintana JM, et al. A prediction rule to identify allocation of inpatient care in community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2003;21:695–701.

• Aujesky D, McCausland JB, Whittle J, et al. Reasons why emergency department providers do not rely on the pneumonia severity index to determine the initial site of treatment for patients with pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(10):e100–8. This trial enrolling more than 1,300 patients showed that emergency medicine physicians tend to hospitalize many low-risk patients with CAP, most frequently for a comorbid illness.

Marrie TJ, Huang JQ. Admission is not always necessary for patients with community-acquired pneumonia in risk classes IV and V diagnosed in the emergency room. Can Respir J. 2007;14:212–6.

Singanayagam A, Wood V, Chalmers JD. Factors associated with severe illness in Pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) infection: implications for triage in primary and secondary care. J Infect. 2011;63:243–51.

Riquelme R, Jimenez P, Videla AJ, et al. Predicting mortality in hospitalized patients with 2009 H1N1 influenza pneumonia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:542–6.

McCartney C, Cookson B, Dance D. Interim guidance on diagnosis and management of Panton–Valentine leukocidin-associated staphylococcal infections in the UK. London: Department of Health; 2006.

Aliberti S, Ramirez J, Cosentini R, et al. Low CURB-65 is of limited value in deciding discharge of patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Respir Med. 2011;105:1732–8.

Choudhury G, Chalmers JD, Mandal P, et al. Physician judgement is a crucial adjunct to pneumonia severity scores in low-risk patients. Eur Respir J. 2011;38:643–8.

Sanz F, Restrepo MI, Fernández E, et al. Hypoxemia adds to the CURB-65 pneumonia severity score in hospitalized patients with mild pneumonia. Respir Care. 2011;56:612–8.

•• Kolditz M, Ewig S, Höffken G. Management-based risk prediction in community-acquired pneumonia by scores and biomarkers. Eur Respir J 2012, Sep 27. [Epub ahead of print]. This paper gives a very interesting perspective on site-of-care decision in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. An integration between a physiopathological approach and severity scores is discussed, and a possible role of biomarkers is proposed.

Lee RW, Lindstrom ST. A teaching hospital's experience applying the Pneumonia Severity index and antibiotic guidelines in the management of communityacquired pneumonia. Respirology. 2007;12:754–8.

Nadarajan P, Wilson L, Mohammed B, et al. Compliance in the measurement of CURB-65 in patients with community-acquired pneumonia and potential implications for early discharge. Ir Med J. 2008;101:144–6.

Karmakar G, Wilsher M. Use of the 'CURB 65' score in hospital practice. Intern Med J. 2010;40:828–32.

Serisier D, Williams S, Bowler S. Australasian respiratory and emergency physicians do not use the pneumonia severity index in community-acquired pneumonia. Respirology. 2012. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1843.2012.02275.x.

Akram AR, Chalmers JD, Hill AT. Predicting mortality with severity assessment tools in out-patients with community-acquired pneumonia. QJM. 2011;104:871–9.

Bont J, Hak E, Hoes AW, et al. Predicting death in elderly patients with community-acquired pneumonia: a prospective validation study re-evaluating the CRB65 severity assessment tool. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1465–8.

McNally M, Curtain J, O'Brien KK, et al. Validity of British Thoracic Society guidance (the CRB-65 rule) for predicting the severity of pneumonia in general practice: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60(579):e423–33.

Francis NA, Cals JW, Butler CC, et al. Severity assessment for lower respiratory tract infections: potential use and validity of the CRB-65 in primary care. Prim Care Respir J. 2012;21:65–70.

Silber SH, Garrett C, Singh R, et al. Early administration of antibiotics does not shorten time to clinical stability in patients with moderate-to-severe community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2003;124:1798–804.

Aliberti S, Di Pasquale M, Zanaboni AM, et al. Stratifying risk factors for multidrug-resistant pathogens in hospitalized patients coming from the community with pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:470–8.

Aliberti S, Peyrani P, Filardo G, et al. Association between time to clinical stability and outcomes after discharge in hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2011;140:482–8.

Aliberti S, Amir A, Peyrani P, et al. Incidence, etiology, timing and risk factors for clinical failure in hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2008;134:955–62.

Disclosure

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aliberti, S., Faverio, P. & Blasi, F. Hospital Admission Decision for Patients with Community-Acquired Pneumonia. Curr Infect Dis Rep 15, 167–176 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11908-013-0323-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11908-013-0323-7